I sometimes fantasize that people in power read Monevator, and that our humble blog makes a bigger impact in the world.

Note: I said fantasize.

Like all fantasies, my mooning is sustained by the odd sigh here and lingering moment there… The policies I’ve mooted on Monevator that later make it into law… The emphasis on some new idea or meme that soon after gets discussed by regulators or raised by a politician.

I know it’s silly. In fact, I’m sure it must be an affliction that’s common to all egomaniacs writers.

After all, if you’re doing your job properly as a writer then you’re aware of the zeitgeist and of its consequences for your readers.

And presuming you’re not ranting in the comment section of the Telegraph or Guardian, you might even have the odd half-decent idea or two that occurs to – oh – several thousand other people at the same time.

Tens of thousands, maybe!

But still… I must admit I swooned like a Jane Austen heroine at the lido when I heard George Osborne announce the new Help to Buy: ISA in his Budget.

A tax-free savings perk that would directly aid first-time buyers who were building up a deposit to buy their first home?

Time slowed down, and it seemed like Osborne was looking directly at me.

“My aides found this great idea on a website called MoneyMotivator,” he said, inevitably getting the name wrong and smudging my moment of triumph.

“Check it out for loads of other good guff.”

Except he didn’t really say that. It was only a daydream.

Just as well, because my idea was better than his.

Say hello to the Help To Buy: ISA

You may just remember my 9 ideas to fix the housing market kicked off with:

#1. New Savings Tax Breaks to Help First-Time Buyers.

My own idea was 4%-paying first-time buyer bonds, like Pensioner Bonds but paid tax-free, to help this stricken end of the market with climbing the mountain that is buying their first home.

The Chancellor’s answer – the only one that matters, since his is law and mine just idle musing – is different.

We are to get Help To Buy: ISAs.

The Help To Buy: ISA is a new ‘one-shot’ special ISA allowance, where the government will boost the savings you put into it by 25%.

So if you save £200, the government will boost that £200 with a bonus of £50.

Actually, according to the official factsheet you can only save “up to £200” a month into a Help to Buy: ISA.

In other words, there’s no scope for high-rollers (/cash-rich house-buying refuseniks) to just dump some spare money into a Help to Buy: ISA for an immediate bung from the government.

(Not that the idea crossed my mind. *Cough*)

Also, the maximum Help to Buy: ISA bonus you can achieve will be £3,000.

Getting that bonus will require saving up £12,000.

At £200 a month it would take around five years of regular saving hit that target .

Are you thinking “hmm” yet?

Standby then, because it gets, well, not exactly worse, but certainly less attractive.

How the Help To Buy: ISA boosts your deposit

You see I’m using the PR spin-sounding words “bonus” and “boost” quite deliberately – because the government doesn’t actually give you any extra money.

Instead, the bonus you have earned from all that Government boosting is only paid when you buy your first home.

That’s sensible from a targeting point-of-view, but still a bit finickity.

Here’s more fine print, lifted verbatim from the Help to Buy: ISA factsheet:

- New accounts will be available for 4 years, but once you have opened an account there’s no limit on how long you can save for

- Accounts will be available through banks and building societies from Autumn 2015

- You can make an initial deposit of £1,000 when you open the account – in addition to normal monthly savings

- There is no minimum monthly deposit – but you can save up to £200 a month

- Accounts are limited to one per person rather than one per home – so those buying together can both receive a bonus

- Only available to individuals who are 16 and over

- The bonus is available to first time buyers purchasing UK properties

- Minimum bonus size of £400 per person

- Maximum bonus size of £3,000 per person

- The bonus will be available on home purchases of up to £450,000 in London and up to £250,000 outside London

I’m glad they didn’t put an age limit on eligibility, given how varied first-time buyers are these days. I do wonder if and how they will police the clause that the money must be for your first home though.

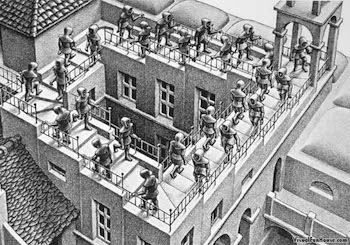

Here’s a handy summary diagram of what it all means, hewn from the burgundy Budget document itself:

How the Help to Buy: ISA will work.

How many ISAs can you take?

One thing I’m not sure about is whether you can open a stocks and shares ISA as well as your single Help to Buy: ISA in the same year.

According to the official details on how the scheme will work:

As is currently the case, it will only be possible for a saver to subscribe to one cash ISA per year.

It will therefore not be possible for an account holder to subscribe to a Help to Buy: ISA with one provider, and another cash ISA with a different provider.

So on the face of it you are okay to open a share ISA and get that ISA allowance for the year in the bag, as well as the Help to Buy: ISA. Just not a cash ISA.

But I’m confused because I thought ISAs (or NISAs as we were supposed to call them after the revamp, and did for about 5 minutes) were now transferable back and forth between stocks and cash versions?

I’ve never done the conversion, however, so perhaps I’m not appreciating some nuance here?

If you can shed any light in the comments below, please do so!

Whether it matters depends on where you buy

At the end of the day, a potential first-time buyer like me has a new savings option that it would seem foolish not to take advantage of.

True, that £3,000 bonus won’t amount to much for those of us who’ve amassed six-figure sums and a few grey hairs trying to keep up with London housing over the years.

But it could be a very useful perk in areas that are more “realistically-priced” (to use the Estate Agent lingo), where salaries are also lower and most Banks of Mum and Dad are probably less able to write huge no-doc loans to children on their whim.

The average deposit size outside of London is now about £28,000, as shown in this new chart from the Treasury:

Source: Help To Buy: ISA scheme details.

On these figures then, the Help to Buy: ISA bonus could be worth around 10% of the median deposit size for typical first time buyers – although median deposit sizes will surely grow far larger in the several years it takes to save up a deposit via this scheme.

If you can take advantage of the Help to Buy: ISA scheme and you think you’ll one day buy a home, then – in the absence of any information yet on interest rates and so on – it seems it would be smart to do so.

It’s free almost-money from the saver’s perspective.

It seems churlish to complain.

Still: Hmm.

Help To Stop A Property Slump

Some critics will argue that the Help To Buy: ISA is just the latest way for the Government to prop up the housing market with taxpayer’s money.

Also, one might suspect that house prices will be higher in a few years by an amount equivalent to where they would have been had this extra Government money not arrived, which would leave first-time buyers no better off than they were before it.

These may prove to be valid points, but I’m not sure.

I suspect that as it will take years of saving to achieve the maximum government bonus, a Help to Buy: ISA may prove too weedy and diffuse to impact the property market much at all.

The spending commitments start trivial, which reinforces that point. In the first year the government expects the scheme to cost it a mere £45m, though this does rise to a heftier £835m by the years 2019-2020.

Remember, aggregate UK property wealth is well over £5 trillion!

Too little, too late

While we’ll have to see if Help To Buy: ISAs do have any impact on property prices, they might not do much for first-time buyers prospects, anyway, especially in the more expensive regions.

As The Guardian reported in its summary of the Help to Buy: ISA’s pros and cons:

Lucian Cook of property firm Savills says the £12,000 limit on savings should prevent a surge in house prices and means the scheme is “more likely to help get buyers over the deposit hurdle in the lower-value, lower-growth markets of the Midlands and the north than say London and the south-east, where significant constraints remain”.

Seems a sensible view. The long timescale required to build up funds does work against both the bubble-stoking potential and the scheme’s usefulness, especially in and around London.

Presuming no house price crash, even modest first-time buyer property price appreciation is likely to far outstrip that £3,000 bonus in most of the country over the next few years, I’d have thought.

House price rises could soon leave your £15,000 saving scheme looking rather weedy.

Help To Buy: ISAs are better than nothing

Sadly, as ever in the UK it seems the best bold plan still appears to be to get a big mortgage as soon as you are able to, and to cross your fingers.

What’s really required though for first-time buyers is lower prices (or at the least flattened prices) due to far more supply – whether that comes from building more new homes where they’re needed, from encouraging people rattling around in too-big houses to downsize to free up the space, and/or from making being a landlord less financially attractive, and so removing some of the competition with less-affluent first-time buyers.

All themes touched on in my housing article and in the many excellent comments made by readers, incidentally, if you’re eager for more.

As for the Help To Buy: ISA, sure it is better than nothing, unless you’re a cynic – in which case it does seem like a pre-Election bung.

Better listen to us next time George old chap.

At least he’s followed up on my Northern supercity suggestion.

(Okay, so perhaps one or two other people have also had that idea… 😉 ).