The trouble with bull markets is making money can seem too much like fun. Meanwhile plunges in a bear market at least get the pulse racing. But investing is boring when markets do nothing, month after month.

Welcome to the investing doldrums.

There’s a section in the Russell Crowe nautical adventure Master and Commander which finds Captain Crowe, ship, and crew literally going nowhere.

Listless on the ocean, day after day, the drama of a sailboat clipping across the seas has been forgotten. A storm would be a relief. Fatalism descends. Dying of thirst on a floating island in the middle of nowhere is not what anyone signed up for (or was press ganged into.)

If the ship doesn’t get going again, they will all go mad or cannibalistic.

Wait, was that a breath of wind? No, just another sighing sailor.

Eventually one of the younger officers is branded a ‘Jonah’ by his superstitious shipmates. The unlucky fellow is harried into jumping overboard, clutching a cannonball.

Grim, but just like that the sails bloom and the ship gets going.

Correlation is not causation? Tell that to a parched seaman when the wind is at his back again.

There be dragons

Of course we’ve all read – or even written – about how good investing should be boring. Get your excitement from your PlayStation or a skiing holiday.

Right, right.

Except you’re reading a blog all about investing. I think it’s fair to say we’re all a little bit more… invested about investing here.

Also, as enlightened 21st Century folk conversant with behaviourial economics, incentives, and ‘nudge theory’, we know the most important thing is to avoid the inner urge to throw anything – or anyone – overboard, just to relieve the tedium.

But just because we know what we should do – stick to our best plan until the breeze picks up again – that doesn’t mean we will.

Some of you are still shrugging. So much, so obvious.

Good for you! Read on for reinforcement, or head out with the other swots for an early break.

However my emails, comments on Monevator, and our Google Analytics dashboard tells me people are getting a bit fed up.

Newer investors ask if it’s fatal they missed the gains from the low interest rate era. Older hands wonder if an unpleasant sequence of returns is derailing their early retirement schedule.

Savings accounts look juicy. And cash doesn’t put the willies up you by lurching into the red. Should we prefer that to all this investing malarkey?

Or what about Bitcoin? The crypto-cockroach is up 75% since New Year’s Eve.

That’s more like it! Maybe this index tracking thing has finally run out of road?

Bonds? Don’t talk to me about bonds. Sixty-farty portfolio more like.

Batten down the hatches

I understand the discontentment. Depending on what you invest in and how, your portfolio may have gone nowhere – or worse, down – for a year or more.

Not much in the grand scheme of things. But also not nothing in a 30-year investing window.

My own portfolio got within a couple of a percent of its (short-lived) all-time high as far back as March 2021. More than two years ago. Despite a bounce in the past six months, I can well imagine looking back at returns that tread water for four or five years from that giddy 2021 spring.

I don’t expect it, but it’s possible. Especially given the regime change to higher rates and inflation.

So don’t be dismayed by macho commentators saying they’re not bothered. Their stance is 100% correct – but there’s no need to be pig-headed about it.

Nobody gets into investing without wanting to make money. It’s better to admit that it sucks when investing is boring or worse. Feel the frustration. Then take counter-measures that keep you going, rather than chucking in the towel.

No doubt we all have a famous investor, money blogger, or economic pundit who we’d have walk the (metaphorical) plank to get our portfolios advancing.

But enough about Nouriel Roubini. What are some practical approaches you can take when you’re mired in a similar going-nowhere market?

Let’s consider a few things that might help, depending on whether you’re a passive investor or a naughty active sort. Followed by some general pointers for all of us.

Passive investing isn’t meant to be exciting…

…but it can be even more challenging when it’s dull as dishwater.

If you have a simple portfolio – a LifeStrategy fund, say, or a two-fund equity/bond split – then checking in when markets are drifting for years can make you feel like a hamster on a wheel.

You’re working hard. You’re stashing away your savings. You see very little to show for it.

You can’t force the market higher. But here are some things you could do.

Look at long-term charts. Remind yourself indices can remain underwater for years. A long trough is not unusual. Doing this won’t help your lousy returns, but you’ll take them less personally.

Count your blessings units. Your portfolio value might be frozen in amber, but is there a more positive metric you could track? Maybe how many units you’ve bought of your tracker funds or how many shares you’ve racked up of your favourite ETF? Or even just the total amount you’ve saved to-date. It is all laying the groundwork for gains when prices surge again.

Remember you’re invested in companies. Now and then I edit my co-blogger The Accumulator’s copy because his talking about ‘Value’ doing better than ‘Small Cap’ gets too much for me. I understand why we talk about baskets of shares this way. But as an old-school stockpicker I think of my investments as companies first, even when in a fund. Why is this relevant? Well, you may struggle to see why an index should rise again. But you might find it easier to imagine that entrepreneurs will keep striving, scientists innovating, and economies growing. These 1 are the reasons why markets go up over time. It’s not just numbers.

Recall the worst is probably past for bonds. I will repeat myself on bonds. Yes they had a terrible 2022. If you owned them then you’d probably rather you didn’t. But that is water under the bridge. The fall in bonds last year set the stage for higher returns going forward – or at least made more deeply negative periods less likely. Bonds should help your overall portfolio return from here.

Don’t forget about income. Talking of bonds, they now sport higher yields. Dividend yields are up too. The mainstream indices may go nowhere, but income will trickle in. Reinvest it. The FTSE 100 index was all-but-flat over an interminable 20 years from 1999. But with dividends you still more than doubled your money. Not amazing, but far better than nothing.

Consider complicating your portfolio. A last – heretical – idea. Most people will do best with an all-in-one fund precisely because such funds hide how the sausage is made. The investor won’t know what is doing well – or badly. So they won’t take wealth-damaging actions in response. However it’s possible you’re somebody who would actually do better seeing a circuit board rather than a black box. An advantage of our Slow & Steady model portfolio is we can monitor the workings. It’s not lifeless inside, even when on the surface nothing is happening. Maybe you could break out some of your equity allocation to a value and/or momentum ETF? Or follow an even more explicitly diversified approach? Or set aside 10% as a speculative sub-portfolio? Doing so may reduce your returns. But if it keeps you interested in investing, it could be a price worth paying.

Active investors can always do something

I stopped prevaricating with a foot in both camps and became a fully active investor early in the 2007-2009 financial crisis. I discovered ‘doing something’ best-suited my personality. It also gelled with my deep interest in economies, innovation, and the markets.

However the greatest strength of active investing is its biggest weakness. In theory you can trade your way around the worst and own the superior stocks in any market. But in practice most fail to do so. They make matters worse.

For instance last year has been dubbed an annus horriblis for UK fund managers. After moaning about ‘dumb’ money pushing prices higher in the long bull market, a majority of active funds failed to beat their index-tracking equivalents when the music stopped in 2022.

So most people will make things worse by stock picking or market timing. But we’re different, right? Or you’re having more fun investing actively. Fair enough, as long as your eyes are open.

Look below the surface. Indices don’t matter nearly as much when you invest actively. There’s always lots of commotion at the company and sector level, even when markets are flat. Last year was great for energy firms, for instance.

Monitor your watchlist. It’s surprising how much any company’s share price moves in a year, between its highs and lows. In confused and direction-less markets, you may find a favourite and typically expensive firm trading cheap for a bit. But you have to be looking all the time to spot these opportunities.

Rotate or recycle. Most of us have shares we know aren’t going to shoot out the lights, but we keep them for their steady qualities. Often they’re interchangeable for another. Procter & Gamble flying while Unilever languishes? There might be a good reason. Or it might be fickle fashion. Consider a swap. The same can hold true for whole sectors.

Look for anomalies. Things get normalized in bear markets that would seem odd when investors are confident. Massive discounts on riskier investment trusts, for example. Or housebuilders or gold miners trading contrarily to the goods they produce. Often there will be cyclical factors to take into account. But sometimes if you correctly judge which signal is superior you can find a bargain.

It’s always a bull market somewhere. I forget who said this, but it’s true. Obviously be mindful of flitting from fad to fad, and being the last buyer left holding the bag each time. But if you can alight on a durable bull market and you know your onions, it can be hugely helpful to have a big whack of your portfolio going up when everything else is doing nothing. Bleeding obvious I know, but you would be surprised how many active investors keep plugging away at the same crumbling coal face for years, rather than seeking a more promising seam to mine.

You probably want to keep thinking long-term. Most successful active investors seem to be long-term players, not frenetic traders. So while I think these trading strategies can be useful, I’d employ them within a framework of trying to tend towards my best portfolio of my best long-term ideas. Unless it’s your strategy and you’ve evidence you’re good at it, beware of ending up with a basket of crappy cheap companies that you have no faith if (/when) things go south. Remember, winners win. Most of the market’s return comes from a handful of great companies. You should be loathe not to own them.

How we can all keep the momentum going

However you invest, the big picture is as eternal as an avocado bathroom suite in Swansea.

Try to be happy. Expected are returns up. Yes you’d rather your portfolio’s prospects had risen for good reasons – higher company earnings or a booming economy – rather than because everything fell a lot last year. Nevertheless those falls blew away a lot of the valuation froth in shares and bonds. It’s reasonable to hope for better returns over the next ten years, compared to 2021.

Save more. You can’t make the market dance to your tune, but you can laugh in its face and throw money at it. Stagnant or even declining markets are a saver’s friend. They let you buy more assets for your money. If you’re under-40 you might even hope global markets drift sideways for 20 years.

Think long-term. The past 12-18 months doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme of things. Save and invest for another 20-30 years and you’ll struggle to see the wobble in your records. True, this is harder if your time horizon is shorter. All I can do is remind everyone that’s why your portfolio should be appropriate for your age (or perhaps your relationship with regular paid work).

Make money through cost reduction and tax mitigation. You can’t control the markets. But you can make sure you’re investing efficiently. Check out our broker comparison table for starters. If you own expensive funds, at least know why. Being optimally-efficient with your taxes, too, can move the dial. Defuse capital gains, for example, if you have unsheltered assets.

Check your portfolio less frequently. An easy way to feel better about a portfolio with a slow puncture is not to know what’s going on. Check in once a year and at worst you’ll get one shock a year. More often you’ll be pleasantly surprised. Most readers will want to look at their portfolios more often, but remember the more frequently you do, the greater the odds of being upset.

Check your portfolio more frequently. Do I contradict myself? Of course! Only recommended for investing nerds who feel out of control when losing money. Proceed with caution, but it’s possible seeing daily gyrations will help you grow a tougher shell, and also further stoke your resolve to put more fresh money to work. That’s what happened to me.

What’s the worst that can happen? It may help to run some numbers on how bad things can get. Look at the most rubbish markets of all-time and apply what happened to your situation. Could you live with it? You wouldn’t be happy – but it probably wouldn’t be the end of the world. Facing your fears can rob them of their power. Imagine if your portfolio was cut in half. How would you feel? The answer may prompt you to take action – but before you do, try the same exercise tomorrow. It may lose its sting, whilst also making run-of-the-mill gyrations of 5-10% feel piddling.

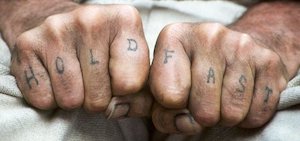

Hold fast

Getting through a miserable period in the stock market is not rocket science. Most of the pointers above may seem obvious to you.

However good investing is simple but not easy.

Very few of us will look back and see brilliant decisions or insights as the making of our investing fortunes. Rather it will be sticking to it through the good times and bad – adding new money, gradually compounding it over the decades – that will deliver our financial freedom.

Choppy markets can make you seasick. Frothy markets can blow you off-course.

When investing is boring, the biggest risk is it can all seem rather pointless.

Do what you can to remind yourself why you’re investing, why you read Monevator, and where you’re hoping to end up.

I’m confident that sooner or later we’ll be going that way again.

Whether you’re a passive or active investor, let’s hear how you’ve been facing the mediocre market of the past 18 months. Even if I suspect for most loyal readers it’s been business as usual. (Quite right too!)

- And inflation.[↩]