The coronavirus crash was bad and the Global Financial Crisis unfolded like a horror movie.

But the UK’s biggest stock market crash in the last 120 years was the drawdown of 1972 to 1974.

The 1970s slump had it all. A property market bubble, secondary banking crisis, massive oil shock, falling pound, rising inflation and interest rates, industrial unrest and global recession were the toxic feedstock for a rampant bear market that inflicted bigger losses than those sustained during either World War or the Great Depression.

The UK market fell -73% from 1 May 1972 to 13 Dec 1974.1 That is 32 months of historic misery.

This chart of the FT 30 index of UK stocks sums up the sinking feeling:

Source: CEICDATA.COM / Financial Times

Not even the -52% bursting of the dotcom bubble could compare with this meltdown.

What the hell happened?

The trouble starts: May to September 1972

The drama begins in May 1972. The UK gives up defending sterling’s peg to the dollar in the face of a widening trade deficit and draining currency reserves. The pound begins a new life as a free-floating currency and heads down. (A direction we’re all familiar with today.)

Inflation and the Bank of England’s (BOE) Bank Rate creep up. The Office Of National Statistics (ONS) records CPI inflation at 7.2% and the BOE’s main interest rate at 7.6% in 1972.

After a summer rally, the market heads into correction territory in September. It’s down more than 10% since May.2

We’re five months into the decline and it’s curiously gentle in comparison to the -32% elevator drop we took in the first month of the coronavirus crash.

Meanwhile, there’s trouble brewing in the commercial property sector.

The lunatic fringe

According to a BOE paper that raked over the ashes of the crisis, rents were rocketing in the early seventies. The supply of office space had been strangled by planning restrictions since the late sixties.

This set off a chain reaction that led to a massive bailout of UK banks called ‘the Lifeboat’.

First, the planning controls were loosened by Edward Heath’s Conservative Government (1970-1974). Faced with a stagnating economy, they also turned on the credit taps as part of a stimulus known as the dash-for-growth policy. But the UK’s industrial sector was slow to take up the easy finance terms and the vacuum was filled by property developers keen to make a killing in Britain’s hottest sector – commercial real-estate.

This heady, fast-buck cocktail was spiked by the vodka of ‘secondary banks’. An emerging category of loosely-regulated lenders (sniffly referred to as ‘the fringe’ in the BOE report), these secondary banks borrowed short on the money markets and lent long to the developers.

Few questioned the strategy as long as the fringe could keep financing their liabilities. However, the risk was building.

Everything was fine as long as there wasn’t a liquidity crunch…

Going downhill: January to September 1973

The stock market opened in 1973 just 5% down from its peak back in May. But things went south from there.

The BOE described the first six months of 1973 as:

…characterised by an almost continuous international currency crisis.

The UK’s trade deficit expanded in 1973 to -2.2% of GDP. That seems routine to us now but it must have seemed mammoth at the time. Nearly 30% of the economy then was accounted for by manufacturing as opposed to just 10% today.3 We were well on our way to our worst trade deficit in the last half century, as the gap accelerated to -4.4% of GDP in 1974.

Inflation (9.4% CPI) and interest rates (9.2% Bank Rate) continued rising through 1973 as the Bank tried to dampen the overstimulated economy.

The stock market deteriorated along with everything else. Finally we hit bear country in August – down 22% over the 15 months since May ’72.

Oil Crisis and recession: October to December 1973

The market really walked off the cliff from October.

The UK had already tipped into recession when The Arab-Israeli Yom Kippur War began and ended in October.

The US and Soviet Union sat like trainers in opposite corners – backing their respective fighters – when the Arabs unleashed their oil weapon on the Americans and their allies.

The OPEC oil cartel cut supply to the US and immediately hiked prices by 17% in mid-October. The oil price was to quadruple by March 1974, deepening the global recession. North Sea oil was still in its infancy and couldn’t cushion the UK economy from the price shock.

The double-headed beast of a falling pound and swelling inflation forced another interest rate rise in November. The stock market took a 16% hit in that month alone and passed 30% in losses since the peak.

Then, somewhere in Threadneedle Street, someone must have muttered, “It can’t get any worse,” because at that moment it did…

…the liquidity crunch chicken came home to roost.

Commercial rents had been frozen by the Government in December 1972. That squeezed real-estate profits, while rising inflation and interest rates made the business of lending to secondary banks with risky exposures to the property market look dubious at best.

The pressure came to a head in November ’73 when London and County Securities could no longer raise fresh loans on the money markets.

The BOE’s report, The secondary banking crisis and the Bank of England’s support operations, records:

It very soon became apparent that some more sophisticated depositors in the money markets were taking fright at their potential exposure to any such institution.

The Bank thus found themselves confronted with the imminent collapse of several deposit-taking institutions, and with the clear danger of a rapidly escalating crisis of confidence.

This threatened other deposit-taking institutions and, if left unchecked, would have quickly passed into parts of the banking system proper.

Behind closed doors, on 28 December, the Bank quietly launched ‘the Lifeboat’. This rescue operation would eventually prop up 30 secondary banks, and be recalled by veterans witnessing the run on Northern Rock nearly 34 years later.

Back on Main Street, OPEC doubled the oil price on 23 December. In a Christmas to remember, Edward Heath declared The Three-Day Week. This restricted the use of electricity by businesses, with predictable consequences.

It would blackout Britain from midnight 31 December.

Contagion: early 1974

From November ’73 to the end of January ’74, London shares shed another 26% and were down 40% since the market top.

The oil shock, fear of contagion in the banking system, grinding recession, crumbling property values, and industrial poison of The Three-Day Week were backdropped by a ballooning inflation genie that refused to be bottled by tightening interest rates.

The miners upped the ante in February by voting to go on strike. Their battle against the Government pay cap and wages that lagged inflation had led to Edward Heath’s Three-Day Week, as the Prime Minister sought to conserve the coal supply that fuelled Britain’s power stations.

Heath sensed an opportunity to checkmate his political enemies and called a general election in February. Drawing the battle lines in stark terms, Heath asked the country: ‘Who governs Britain?’

The voters responded: “Not you, mate!”

The Conservatives lost their majority. Britain returned its first hung parliament since 1929 – and the last until 2010. It seems the mischievous British electorate does love a bit of political paralysis in a crisis.

Harold Wilson entered Number 10 at the head of a minority Labour Government in early March. Chancellor Denis Healey – whose topiary-free eyebrows delighted a generation of school children – then administered some stiff medicine in his March Budget:

- The basic rate of income tax was upped to 33%

- A new 38% band introduced

- The top rate increased from 75% to 83%

- Corporation tax up 12% to 52%

- VAT slapped on petrol4

The stock market delivered its verdict – a 21% drop in March. The largest monthly fall of the entire drawdown.

We were 22 months in and the market had lost 50%, surpassing slumps in both World Wars, The Great Depression, and the 2008-09 Financial Crisis that lay in wait.

The worst is yet to come: May to December 1974

After a brief respite in April, and after two years of decline, the market went on its worst run yet: a five-month losing streak from May to September. This knocked another 37% off equities.

1972-74 losses mounted to -65% – a slump not even the the future dotcom bust could top.

Meanwhile, the UK’s banking crisis took on an international dimension. Massive foreign exchange losses and fraud shook confidence in the financial system across Europe and the US.

As fear mushroomed, the BOE increased its liabilities as:

There was still a significant risk that an isolated default by a UK bank, in the highly charged atmosphere of the time, might have triggered a chain reaction.

Rumours spread in November that one of the four main British banks – the NatWest – was on life support from the BOE. The NatWest issued a denial. In a remarkable sign of the quaint times, that quashed the rumours as opposed to inflaming them, as would surely happen today.

Another sign of the times was Denis Healey notching up a hat-trick of Budgets in 1974, with Labour scraping a slim majority in the October ’74 election. The market greeted that development with a further downward leg of -18% from November through December – finally hitting bottom on 13 December – with a real return loss of -73%.5

1974 was the UK stock market’s worst single year since 1900. The following stats (courtesy of the ONS and Sarasins) sketch the economic conditions that crushed business and investor confidence:

- -2.25% GDP contraction

- 12.1% interest rates

- 15.5% rise in CPI inflation

- -13% corporate profits

The rent freeze was finally lifted in December ’74 and property prices began to rebalance. Unemployment continued to rise in 1975 but the market snapped back that year with the mother of all mean reversions – a 99.6% real return.6 The rebound made 1975 the greatest annual performance in UK stock market history (dating from 1900).

However a 73% loss requires a 270% gain before you return to the black. After 32-months the market had only touched bottom. It would take another nine years to breakeven again in real-terms – a milestone passed in 1983.

Hopefully you and I will never experience anything like the 1972-74 stock market crash. But it’s a cautionary tale of the tape that shows what can happen, and why equities will only reward those who can handle the risks.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

- Sarasin Compendium Of Investment 2020. [↩]

- Monthly price data for the FT 30 index from Investing.com. [↩]

- Changes in the economy since the 1970s, ONS. [↩]

- Not to mention sweets, ice cream, soft drinks and crisps. Those school kids weren’t so amused now. [↩]

- Sarasins Compendium Of Investment 2020. [↩]

- Barclays Gilt Equity Study. [↩]

Comments on this entry are closed.

Though to be fair, that 9 year wait to break even is only really relevant if you were unlucky enough to invest your entire lump sum on the very eve of catastrophe

An amazing story, well told. Thank you!

A sobering tale, and a series of events that must have caused great suffering to those retiring (or wanting to!) during those times. I need to reread that whenever I think that gilts are currently too expensive and that equities are king.

Nightmare out of a clear blue sky!

Can/Could/Will happen again

Would a prepared investor cope?

I had just started working-never noticed it-completely passed me by

If you are in a job -keep working-hopefully

If retired -a good slug of bonds and 2 years cash might see you through

Mainly a real warning to those about to retire-get your “ducks in a row” sooner rather than later

Sacrifice some equity growth for bond safety in good time before retiral

Retiring into a Downturn is not recommended

Your Portfolio might never recover as you need to make withdrawals to live!

xxd09

So, by that telling we’re at about, what, November / December 1972?

@xxd09 – yes, next January is my Lamborghini day so I began putting my 100% equity portfolio ducks in a row last November by shifting 10 years of expenses into Fixed Income as I realised my life expectancy in my job is distinctly limited… Every year’s salary is a bonus and for that year I intend to move 6-12 months expenses back into Equities until I’m 75/25 or maybe 80/20. I’m accumulating a small DB pension which with the state pension should adequately cover my floor, so don’t need too much in Fixed Income.

But around March I definitely didn’t get spooked by C-19 but made a strategic reallocation into 25/75 where I’m currently sat. I don’t think the market has priced in 10% falls in GDP or mass unemployment and I figured the upside, with this bull market so long in the tooth, was limited but the downside could be severe. Though hopefully not as bad as TA’s horror story.

Whatever happens, and I’m well aware of the perils of market timing, by protecting my capital I should have enough to see me through. I guess the 6-12 months rebalancing may have to be more like 12-18, I’ll have to run some (back of the fag packet) simulations. Now, if inflation picks up…

When I started as a blue button (look it up!) in 1986 one or two of the older hands still spoke about the 1972-74 bear market and, rather like old soldiers telling war stories, did so with real trepidation in their voices. It was not a happy time, even at broking commission rates of 1.65% on the first £5,000 and so on. It was good training though for the 1987 crash which, if my memory serves me, was mostly spent in a wine bar.

It’s reminders like this article which make me wonder about the 60/40 b/e portfolio v a bucket strategy – it’s all very well re-balancing your bonds into equities but when the falls are of this magnitude ones “x number of years in cash or bonds” could get eroded rather substantially and I guess, with many of us, we’d just lose out nerve and forget about re-balancing. Maybe formalising that fear by having a fixed number of years in cash/bonds which doesn’t ever get used for re-balancing is the way to go. I imagine this has been covered before.

I was at school and remember it was literally freezing in the classrooms over the winter because there was no heating of the school, due to the oil crisis. Nor, given prevailing attitudes, were we pupils allowed to wear our coats and other outdoor clothing in classrooms, so had to – again, literally – sit shivering for hours every day . I’d only recently come to live in the UK and thought it was a third-world country compared to countries in Europe and Asia I’d lived in up to that point: a real basket-case. Part of the reason I voted Remain was to avoid having to go back to what Farage et al see as some kind of golden age in the UK, but I recall as quite the opposite.

I enjoyed reading it. But I do think you need to be careful publishing these sorts of stories in this climate on a site that champions passive investing / no market timing. I am pretty steady when it comes to buy and hold but this story has started me thinking I should sell and move to cash. Things feel bad at the moment (in a number of ways) and 8 years to break even. Maybe this feeling just reflects my personal frame of mind right now…..

I’m always slightly uncomfortable about phrases like “The UK market fell -73%..”

Wouldn’t fell (by) 73% make more sense?

I may be wrong of course 🙂

The main lesson is invest globally (market weight).

@gadgetmind

> must have caused great suffering to those retiring (or wanting to!)

There were mostly DB pensions though.

Remember investing as more difficult then. Shares were certificated and you had to engage a broker to buy and sell with dealing and settlement delays and no electronic transfer of money. Instead of the internet think cheques and post.

I do wonder how widespread holding shares in the UK was in that era. Does anyone have any insight into who was holding shares? Without digging into it, all I have are stereotypes of the city gent…

I was there in 1972-74 but in my romper suit. My Dad still carries psychological scars from the period, though. He wasn’t exposed to the stock market but his thinking is heavily influenced by his experiences of rampant inflation and the industrial disputes.

Researching the tale puts today’s woes into a better perspective for me. We seem to be facing such an imbroglio of problems but it was ever thus. I only briefly alluded to the fact that there was a superpower confrontation going on at the time.

I kept finding myself a little staggered by the contrasts in the economic environment between now and then. Sky high rates of inflation and interest, especially as the 70s wears on; conservative governments in the UK (and US) imposing price controls; incredibly high income tax; the scale of our manufacturing base before the next decade or so laid waste to it. Almost a different country.

@ Marco – that’s an incredibly on point observation.

@ Berkshire – you’re right and I wrestle with that every time I do it. Somehow I’ve fallen into the habit because I think that minus point emphasises the loss. I do that because it’s so hard to feel loss when you only read about it and I want people to have a better understanding of what they’re in for in the markets. What risk can mean.

@ Richard – hopefully I haven’t spooked you too much. This is why I’m writing a lot about market crashes right now. We had years of an incredible bull market. Then a near-death experience and a very lucky escape – for now. We still get lots of readers questioning the point of any asset other than equities and possibly gold, so I guess I’m trying to highlight:

1. It may well not be over. Other market crashes like this one and the GFC have lasted much longer so be prepared for the long haul. If you found March scary then you could think about using this respite to shift your allocation a little into defensive assets. I’m not advocating selling out of equities wholesale, but reassessing your risk tolerance in line with some of the ideas in this piece could be worthwhile:

https://monevator.com/how-to-estimate-your-risk-tolerance/

2. This is the nature of risk. The reward we all hope to reap from equities can be hard won and look like a fool’s errand for a decade or more. I’ve read pieces that describe how for years the only people that turned up at shareholder’s meetings were ‘old fogies’ because a younger generation thought equities were a mug’s game. Studying stock market history makes me think hard about what I could be in for, but I’m also pretty sure it’ll keep me sane if things get really tough. There’s an incredible book called The Great Depression: A Diary. I had a new respect for bonds, and a new understanding of how a market could drop 50%, and then 50% again, after reading that.

@ Ruby – you’re right, there’s a fair few advocates of a ‘back-up’ portfolio of low risk assets. Bottom line is it’s a drag on returns if all goes well for you, but is very handy if you’re handed a bad sequence of returns. Much depends on personal temperament, I think. How much security is enough?

@ Brod – that did make me laugh. Love your strategic manoeuvrings and the idea of a Lamborghini Day.

@ Tyro – very interesting. Old Blighty was dubbed ‘The Sick Man Of Europe’ at the time. We’ve definitely got basket case potential. Lord knows what’s in store but I can only hope we navigate the next few years with a little more aplomb than the performance of the last 6 months.

Working class people did not own shares in the 70’s. It was a middle class thing and then via intermediaries. At my level wages were paid in cash in little envelopes and NI was literally a stamp stuck on a card. Owning shares would have been a bragging point and meant you had a ‘ stockbroker’ ( pre big bang). The level of savings must have been lower, and savings meant cash in a building society to us ( as a precursor to a deposit for a house).

Well that my memories of 40 plus years ago anyway. Being a stockbroker was a golden ticket.

@ Mr O

Absolutely right. I remember the poshest part of the leafy suburbs was known as ‘the stockbroker belt’!

But I don’t think owning shares (or at least individual company shares) was a common middle class thing; people would buy funds, but at scandalous fees with enormous trail commissions and never realise how they were being ripped off.

And to get a mortgage, you first had to save with the same Building Society (irrespective of the rate on offer) for at least 2 years. And the rules were kafkaesque – I remember being turned down on a mortgage because it would have been £350.00 more than twice my salary plus half my girlfriends!

Them were the days:-))

Nice piece. What the 70s demonstrates is the impact of the last failure of a global economic regime. Unfortunately, by the early 70s, major imbalances had built up in the Bretton-Woods system. The pressure built until it blew up. Inflation, real yields and risk premia all exploded higher, taking asset prices massively lower.

On the positive side, we don’t have fixed exchange rates anymore. Floating FX rates do provide an automatic stabilizer, a pressure valve. The other positive is that regime change can be good for the younger generation. The 1970s was a problem for those retiring (albeit limited by most having DB pensions). Conversely, for the Baby Boomers, the 1970s turned out great. RPI up 325% but earnings up 392%, a real gain of 21%. At the same time, asset prices got clobbered lower, allowing that real income to buy much more. Essentially, the last 35 years or so have just been a retracement of the 1970s move up in real yields.

On the negative side, rather like the 60s, many of the policies currently being enacted are simply kicking the can. They either lead to the purgatory of secular stagnation or the hell of economic regime change.

Historically, most of us will see one regime change in their working life. It’s impossible to predict when the phase change will occur and how long it will last. I was hoping that I’d see one before I retired since it would be easier to take a judgement about retirement once you seen it start. It seems that can kicking will now delay the volatility associated with that change beyond my end date.

I remember the powercuts, but not only working 3 days a week. I remember inflation being so high salary was increased every payday (shown as a supplement to the basic figure). My father probably owned shares in his employer (ICI) from some incentive scheme. He certainly did later.

I was completely oblivious to the fall in the markets, but not to the rising prices, but those high interest rates helped my savings grow, at least in nominal terms.

@Ruby & TA:

Investing during retirement is a rather different matter from investing for retirement, as retirees worry less about maximising risk-adjusted returns and worry more about ensuring that their assets can support their spending goals for the remainder of their lives.

A primary goal may thus be to form portfolios with asymmetric payoff profiles that have less downside than if normally distributed.

In this new retirement calculus, views about how to balance the trade-offs between upside potential and downside protection can change. Retirees might find that the risks associated with seeking return premiums on risky assets loom larger than before, and they might be prepared to sacrifice more potential upside in order to protect against the downside risks of being unable to meet spending objectives.

Long-time reader, first-time poster here. It’s a myth that you needed your own stockbroker to trade shares in the early seventies. Your own bank would have been happy to pass orders on to a local stockbroker (in the nearest large town – not the City) for you. My father regularly traded shares via his bank (Barclays). As far as I recall he only paid the standard (high) stockbroking commission. Doubtless the bank would have received a cut from the stockbroker. In those days there were regional stock exchanges – not every trade would have been on the London Stock Exchange.

I believe share ownership was then more widespread than you might think. Mass-market newspapers like the Sunday Express had extensive city columns and share tips. I remember my father commenting how a share tip in the paper would move a price the next trading day.

We were definitely middle class but certainly not wealthy – not in the stockbroker league! My father had a modest salary but some inherited wealth. I think it was fairly common then for middle class people of relatively modest means to own a few shares in mainly blue chip companies.

@Accumulator – but what we really want to know is how the Slow and Steady Portfolio would have performed!

Great post. Brought back many memories of much happier and less divisive times but then I was much younger.

Oh, I forgot to say that in those bygone days the bank would have even stored the share certificate for you in its own strong-room.

I got bored so went on a hunt on Shareholder numbers in the UK in the 1970s.

Individual ownership of the stock market rapidly declined between 1970 and 1990, falling from about 50% to just 20%

Now it is 12.3% (UK Shares), Unit Trusts 9.5%

4.1% of the UK of the population in 1970 were investors

Sample UK holding size was 21, average holding value (1963) was £860

In 1949 the investor was described as “to be found in retirement in the pleasanter climes of Southern and South-Western

England and North Wales. “

@Marco, yes going global would have significantly helped. For the period discussed, start of May 72 to end 74, the MSCI World Index dropped only 20% (in GBP), but that includes dividends which were much more heavily taxed in those days. Peak to trough for the world market did not coincide precisely with the carnage in the UK though. In that period, peak to trough was down 40% from end 72 to end Sep 74.

I was about to say the Slow & Steady portfolio would have done well by comparison but then UK gilts got caned as well from memory. I wouldn’t be allowed linkers though, so if we can just time-travel back and change that allocation to gold we’d be alright.

@ Simon T – wonder if that decline was the knock on from this early ’70s debacle? Although I thought the 80s was meant to be the advent of the shareholder economy. Even I got some British Gas shares then and I was at school.

@ Economiser – I remember power cuts too, although that would have been a few years later for me. I’ve never heard of the weekly wage packet supplement before. Scary.

@ ZX – yes, I know a few baby boomers who’ve done rather well with their wall-to-wall DB pensions and extensive properties they bought for five bob. They don’t know they’re born (as they always used to say to me when I was surrounded by Taiwanese toys and cosy central heating).

When’s your Lamborghini Day?

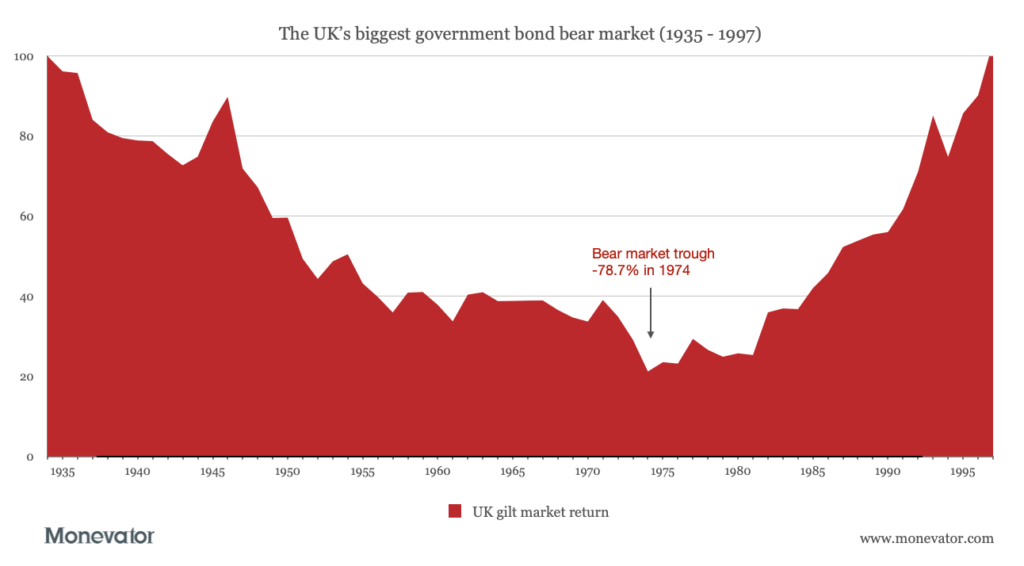

@Accumulator – you posted on April 28th in your comparison of US Treasuries and gilts that gilts fell by 50% between 1972 and 1974.

If inflation-linked gilts had existed at that time, they would have afforded you good protection. I’m guessing that global gov. bonds would also have stood you in good stead too.

@Al Cam – couldn’t agree with you more about portfolio construction for retirement. TA’s previous posts about how different types/duration bonds performed during previous major equity corrections are v. useful in this respect.

Yes in that bygone era you used the banks as a further intermediary to the stockbroker, as I had to in the early 80’s. The Howe budget of 1980 was austere and there was little return on shares until after the Falklands as I recall. Then it was the big bang, Lawson, PEPs and off we went….at least until 1987

@Grumpy Old Paul

a) Good history of UK index linked gilts at:

https://www.dmo.gov.uk/data/gilt-market/index-linked-gilts/

b) safety first approaches in general (like Floor & Upside) strive to provide such an asymmetric payoff construction

@ DavidV – very interesting. That’s stirred an old memory for me. My grandmother on the Irish side of my family was a widow by the time I was born. My grandfather had left her some shares and she must have drawn an income from them to some extent. I remember a story that, after she passed away, the old share certificates came to light and the vast majority had long since gone bust. There must have been the odd ten-bagger among them but no Berkshire Hathaway that I’m aware of.

Again, she wasn’t one of the pin-stripe brigade, she ran a small BnB and liked to max out her duty-free whiskey allowance when she came over to visit.

@TA. Exactly. She did nothing with the shares over all those years because it was outside the bounds of her imagination. A neighbour was widowed in 1988 and thought she was in financial straights. She was clearing out the paperwork some time after and had a few bin bags for burning. Fortunately a relative sifted through it and found £300k of share certificates and saved them from the fire. Of course it could have been remedied subsequently by writing to each registrar and proving identity but a palaver and how would she have known she had captured them all. Basically husband was too lazy/ cheap to deposit them with a custodian: another obstacle we don’t have now.

I think settlement times were T+7 when I first started to invest.

UK share trading used to be done over fixed 2 week periods. All trades done in each period would settle on the same day. Not sure when it moved to T+X, or what X originally was, but suspect this happened around the time of the Big Bang. Financial Big Bang, not the start of the Universe 😉

When I first bought gilts it was through the Post Office! That was the cheapest route.

@Naeclue. I am wondering how old are you! However it does show what a recent thing day trading is. Presumably short term volatility is also rather a recent phenomenon, or has been amplified.

Was it like that in the US? I’m thinking of those old news reels of the Wall St Crash – people desperately trying to sell and staring in horror at plunging prices on the ticker tape. Did they have to wait two weeks to settle?

So many more people would be passive investors if their certificates were locked in some bank’s vaults.

The pound dropped from around $2.61 to $2.31 during this period, so $ investors in the UK stock market had an even worse time than local investors.

Gilts did get hammered in this period as well. Not quite so badly as equities, but gilts had actually been in decline for 10 years before this event. Amongst my dad’s things I found a War Loan certificate dated 11 May 1962. Unfortunately he put around 60% of his savings into War Loan back them, persuaded to do so by my grandfather who said “Prices have never been so low”.

Out of curiosity I tried to find the price my dad paid when I found the certificate. Could not get it exactly, but it would have been around 65% of par value, for a running yield of about 5.4%. With inflation at 2-3% I can see the appeal. They bottomed out somewhere around 20% of par in 1974. He did not see the price he paid for over 30 years, by which time the nominal value had been been deflated by at least a factor of 10.

This might be of interest to those who think long dated bonds are good investments, or at least good portfolio stabilizers, at current prices.

@Naeclue – it was 14 day ‘account’ periods when I kicked off in 1986 and, as you say, each account was settled on the same day. What all the punters used to do was buy on day 1 of the account and sell on day 14, hopefully at a profit and thus didn’t have to settle. If the punt hadn’t quite worked out, and if one had a tolerant broker, one could ‘cash and new’ – sell in the old account and buy in the new (a bit like a bed and breakfast deal) and not have to settle at all. Alternatively, one could just sell and settle the amount of the loss. Cash and new could be done for short trades too I recall and I believe there were plenty of brokers doing this routinely during this period. Sell in 1972 and buy back in 1974 would have been pretty handsome.

@MrOptimistic – there was plenty of volatility pre Big Bang but, because there was no electronic trading, the ‘circuit breaking’ routine was a bit different. Rather than the regulators limiting anything I believe the form was that the senior partners of the jobbers (the market makers of the day) got together and essentially went on a go slow to take the steam out of trading – by go slow I think it involved widening spreads and getting an early train home.

Could be wrong, but I think settlement of UK shares could take up to 3 weeks, settlement date occurring 1 week after the end of each 2 week period. That was nothing to stop you buying and selling again within the 2 week period, with the deals netting out on settlement day.

This was an archaic system even at the time. The City was a high cost, inefficient, nepotism ridden mess back then, like much of the rest of our industry. Thatcher hated it and tore up the rule book. Many of the people who worked in finance were totally out of their depth when the foreign banks moved in and did not last very long.

@Naeclue – and many of of the foreign banks were completely out of their depth too, didn’t really know what they were getting to and didn’t last long either. The integrated house sounded like a great concept but it worked for very few. The smartest, Schroder’s for eg, pretty well left it alone. That’s family money for you.

@Ruby, yes that’s it “Account periods”. As you say, the delay in settlement did not get in the way of trading. In those days you simply traded over the phone, essentially using limit orders much as now. You then got contract notes in the post and had to post off the certificates if your bank (or broker if you were posh) did not hold them.

Most of my trading at the time was just selling privatisation shares.

@Ruby, “”..and many of of the foreign banks were completely out of their depth too.”

You are right there. Many of them thought a quick way in was to buy an existing bank or brokerage and ended up paying far more than the old firms turned out to be worth. Even our own banks, such as NatWest buying County, fell into a similar trap though.

Great piece! I grew up on horror stories of the 70s from my father and grandfather, and this definitely chimes with their tales of woe.

Regarding international investing as a hedge against this sort of thing, everyone pointing this out is absolutely right from a modern point of view, but my understanding is that capital controls would have made this impossible /impractical at the time.

@Naeclue:

Re “This might be of interest to those who think ….”

Still with you on that. And, thanks for illustrating the point with your real-world example – stories such as your Dads usually help to clarify matters

@Naeclue – but does anyone hold bonds to maturity? E.g. a ladder.

The effective duration of the three (!) bond funds I hold is around 7/8 years. So not 25/30 years.

Maybe a little off topic, but in the vein of ‘in the old days’. My Father died in 1991, and going through his things we found a life assurance policy from 1929 – taken out on his 11th birthday- for the sum of (something like) £10.00. The artwork on the certificate was magnificient, a sight to behold.

I submitted it to the Dublin Life Assurance company who issued it, who sent me a cheque for £100.00 because they wanted to frame it and put it on the wall of their boardroom.

Not sure what the return on that was though, but nice, all the same.

@Brod, all bonds are held by someone at maturity. If you hold a bond ladder, there is of course no reason you need to hold to maturity. For many years I kept maturities between about 7 and 14 years. I would roll the shortest dated bonds over each year when I rebalanced. With bond ETF charges so low now I probably wouldn’t bother with all that.

When my dad bought War Loan, the duration would have been about 20 years. Certainly with 6/7 years duration you should not see anything like the volatility he experienced. Hopefully we will not see inflation explode the way it did in the 70s either, but even at the government’s 2% target, that’s a depreciation of 45% over a 30 year retirement. Close to 60% if we get 3% inflation.

Nobody knows what all this supposedly cheap borrowing will lead to. The mainstream opinion is that it is affordable, but mainstream opinion is frequently wrong and the 1970s show how quickly inflation and debt can spiral out of control.

We know that the trend in real yields has been on a downward path for hundreds of years. There are very clear reasons for the that trend. It makes total sense. Moreover, the current negative real policy rates are not that amomalous, being observed over 25% of the time since 1700. Negative real Gilt yields have been seen over 20% of the time.

The issue is that the downward trend is punctured violently at periodic intervals. Notably, real Gilt yields were negative during the 50s and into the early 60s when the Govt again used “financial represssion” to reduce the real value of debt incurred during WW2. And what did that lead to … the 1970s!

That for me is the key problem. We’re again using financial represssion to force real yields down, to deliberately push up risky asset prices. I can’t quite see major inflation risks on the horizon. Aggregate demand is on the floor. It feels more like the end of the Gilded Age than the end of the 60s. That can change though. There’s a decent chance, however, you will be able to spot the key transition. You had over 6 months between the end of Bretton Woods (Aug-71) and the big drops in many markets.

@TA. No interest in Lambos. I don’t enjoy driving and enjoy the servicing charges on fast cars even less. Retirement-wise I don’t really have a set “number”. I’m went well over 100x typical annual spending levels more than a few years ago and yet there is always something else you need to save/invest for. It’s arguable that a very good year at work plus a very good year for my portfolio has finally pushed me even over those targets. It’s all too subjective, though, a constantly moving metric. So a decade ago, I just set an age to retire: 50. About 3 years left.

@Naeclue (44). A duration of 20 years in 1962 for War Loan seems rather low, and at the time would have been unknown. 3 1/2% War Loan was undated and was finally redeemed by the government in March 2015, 83 years after its issue! Or was there another less infamous dated issue of War Loan that I have not heard of?

@Naeclue,

Weren’t some War Loans and Consols undated?

@Grumpy, yes war loan and consols were both undated, but they were callable. War Loan was called in 2015. I checked my dad’s bank statements to make sure he was repaid.

@David, duration of an undated security is 1+1/y, where y is the yield. The yield was somewhere around 5.4%, which gives a duration of about 20 years. Duration is always knowable, you just don’t know what it will be in the future 😉

@Naeclue. Thanks for that explanation. It just shows how little I know about bonds. I knew that duration and time to maturity were not the same, but had thought they were never very different. Bonds seem so simple when you first think about them, but as this site has revealed so many times, the complexities are numerous.

@David, to get very geeky about it, duration of an undated callable bond is not precisely 1+1/y, but when trading at 65% of par, the call option will not a lot of difference.

@ The Borderer – Lovely story about your Dad’s heirloom life assurance. He would have been proud of you for ten-bagging the value!

@ ZX – It sounds like you’re in the enviable position of having plenty of options. The ability to walk away possibly makes the need less urgent? That’s certainly the case for me, and it turns out I’m world-class at coming up with new things to save for. Age-wise we’re very similar.

@Grumpy

Re: safety first portfolio constructions (see my comment #28 above):

If I correctly understood your comment #36 to the Slow & Steady update post of June 30th, then you are already structured in a safety first manner – with your DB scheme (and state pension too?) providing your Floor. Apologies for not making this clear above.