One of the most critical factors when considering risks and rewards in investing is time.

- Some investments look great over certain periods of time and terrible over others.

- The length of time you hold a particular investment can change its risk/reward profile.

- Small percentage differences add up over the long term.

- We also need to think about volatility. In essence volatility describes how often or how far a particular asset goes up and down.

Does this look like a good investment?

The graph shows the great stock market crash of October 1987. London’s largest companies lost one-third of their value in just a few days!

How would that make you feel?

Here’s what happened over the next five years:

The big crash is still visible, on the left hand side, but UK shares were back to their pre-crash levels just 18 months later. The stock market then went basically nowhere for the next three years.

The best time to invest was when it felt worse – right after the crash!

Past performance is no guarantee of the future. But we shouldn’t ignore its lessons.

Today the Great Crash of ’87 barely registers on this four-decade graph of the FTSE 100:

Will the coronavirus crash of Spring 2020 – that very visible scar on the right of the graph – look similarly trivial in a few decades time?

The long-term might not be long enough

You might conclude markets always come back if you wait long enough.

But investors who bought Japanese stocks in the late 1980s would differ.

Two decades on from hitting a high of 38,957 in December 1989, the Japanese 225 index was still two-thirds below its previous peak:

Indeed it was only in February 2021 that the index finally breached the 30,000 level again.

And as I write the Nikkei 225 is still far below its all-time high, more than 30 years later.

You say you’re a long term investor. But how long is long term?

Lower-risk assets can still lose money

Let’s twiddle the dials on the Monevator Investing Time Travel Machine to consider another historical example.

Does this look like a good investment?

That graph shows the progress of a UK gilt fund between 2008 and the start of 2012.

Pretty nice.

Gilts – UK government bonds – are the safest investment after cash for UK citizens. So a fund invested in gilts should preserve your wealth, right?

Well, here’s how the same gilt fund did between the start of 2012 and autumn 2013:

Investors in this lower-risk fund lost money, even after reinvesting all the income from gilts.

And here’s how that gilt fund did compared to UK shares:

The ‘safe’ gilt fund (blue) fell in value 3%, while the ‘risky’ FTSE 100 (red) increased by 15%. (Aside: shares were more volatile.)

Same difference

I am not making the argument that you should own shares versus bonds, or vice versa.

Let alone for avoiding Japanese markets, or anything so specific.

With these examples I’m just trying to illustrate the right way to think about investing.

Because any investment must be considered over different time scales – not just the past month or even the past year.

So-called safety is relative, and often depends on valuation.

And things can go down and bounce back, or stay down.

Most of us have no skill at judging how different types of investment will do – especially over the short to medium-term.

Usually it’s best for most people not to try.

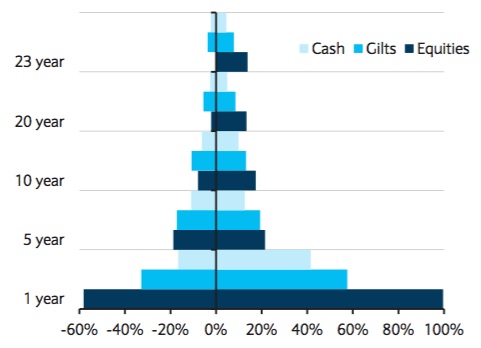

Time and diversification

Unfortunately we don’t have a time machine. We don’t have a crystal ball, either.

So we cannot invest in the past with hindsight. And we cannot be sure of tomorrow’s winners.

However we can spread our risk among different kinds of investments (or assets).

By holding a collection of assets, we can smooth out the ups and downs. We might even turn the volatility we’ve seen above to our advantage!

- Recipe for poor returns – Chop and change holdings to chase recent strong performers. Ignore history, diversification, and valuation.

- Recipe for good returns – Have a plan, stick to it, consider neglected asset classes. Remember history and reversion to the mean.

Different kinds of investments – such as cash, bonds, property, and shares – are called asset classes.

For example, cash is an asset class. Whereas Tesco shares are a specific investment (a tiny piece of ownership of the giant grocer) within an asset class (shares).

Here is a typical spread of returns from six different asset classes over an illustrative 10-year period:

It doesn’t matter what the different assets are for our purposes. This is just an example.

The important thing to look at is the shape of the graphs, and the numbers in the following table.

| Asset | Total Return | Annualised | Worst year | Best year |

| A | 34% | 3.3% | 1% | 7% |

| B | 48% | 4.5% | -7% | 8% |

| C | 80% | 6.7% | -16% | 19% |

| D | 165% | 11.4% | -21% | 57% |

| E | 36% | 3.5% | -6% | 8% |

| F | -6% | -0.7% | -22% | 20% |

Note: Numbers for illustration only

In this table:

- Total return: how much you’d made by the start of year 10

- Annualised: the equivalent annual rate of return

- Worst year: the lowest return in a single year for that asset class

- Best year: the highest annual return for that asset class

By looking at this series of returns and graphs, we can see that:

- Different assets behave differently at different times

- The smoothed annualised return hides a lot of big yearly swings

- Small differences in annual return can make a big difference long-term

Why pick one when you can have them all?

If only we had that table in year one! Then we’d have put all our money in Asset D and made a fortune.

But we didn’t and we never will, except by luck.

We can’t be sure about the future. As for being guided by the recent past, if anything, the best asset over the prior ten years is more likely to do relatively worse over the next ten years. (But again, no guarantees).

What if we hedged our bets and split our money across all six assets?

Here’s how things would have turned out after a decade.

| Total Return | Annualised | Worst year | Best year | |

| Portfolio | 59% | 5.3% | -3.5% | 14.7% |

Note: Numbers for illustration only

- The worse year we’re down 3.5%, versus the worst 22% decline in Asset F

- The best year we’re up 14.7%, compared to the best 57% rise in Asset D

- Our return of 59% beats four of the six classes’ individual total returns

- Volatility is lower compared to holding either one of those outperforming assets. Which is nice

What if we tried to take advantage of the volatility, by trimming our winners and adding to the poor performers every year?

As a simple illustration, here’s what happens if every year we sold everything and then reinvested our money again, equally split between the six asset classes:

| Total Return | Annualised | Worst year | Best year | |

| Portfolio | 61% | 5.5% | -3.6% | 15.4% |

In this illustrative example, annually rebalancing across the six assets classes improved our total and annual returns.

Key takeaways

- Holding a mix of different kinds of assets can smooth your returns

- The peaks and troughs are lower, and so are the maximum losses

- The price you pay for diversification is you will never make the best returns achievable (in theory) by holding only the best asset class

- But since you can’t know in advance what will do best, is that really a downside?

This is one of an occasional series on investing for beginners. You can subscribe to get our articles emailed to you (we publish three times a week) and you’ll never miss a lesson! And why not tell a friend to help them get started?

Note on comments: This series is for beginners, and any comments should reflect that please, rather than confuse or make irrelevant points. I will moderate hard. Thanks!

Comments on this entry are closed.

Nice clear article, though it might be worth explaining at some point in the future why the annualised return is not the total divided by 10!

I’d also highlight that while gilts haven’t done very well this year, the fall is _much_ less than the equities falls you have shown! Gilts are inherently less volatile, though of course people shouldn’t equate volatility with risk!

@Greg — Well, I do say that the gilt fund is down 3%, and that the FTSE fell a third in 1987.

It’s not really an article about gilts versus equities, as I state in the copy. The takeaway should not really be any thoughts about specific asset classes, though I concede that’s hard.

When I first used some of this material in some help I was giving a friend, the assets A, B, C and so on were labelled as the actual assets. And she started saying “so I should buy gold then?”

Which is the complete opposite of what I was trying to get across! Hence I removed the labels here.

The takeaway for a new investor should be “if I am looking at a few months of performance, or even a few years, I am not seeing the whole picture” and “everything except cash (though not excepting the interest rates on cash!) goes up and down”.

I have read countless articles this year saying “Investors in supposedly safe gilt funds have been shocked this year to find their fund is down in value…” – but while the fall is interesting enough, it should not be a shock to anyone.

This article is a pointer to *know your asset classes*, and understand why they are best held together for most people.

@Investor

Thank you for the clear examples. At last, I really get it

@Mike — Great stuff! Glad to help.

TI,

You certainly have a gift when it comes to providing clarity in what can often be a confusing and complex area. I think you should write a book on investing for beginners – I’m sure it would become a best seller!

@ The Investor,

In this weeks weekly round up could you include a nice read relating to bonds. They have left me a little confused… As prior to this bond bear market all I’ve read is that they are the safest asset class… Yet they are providing the most drag at the moment on my portfolio. Inevitably rates will rise as the economy picks up pace at some point in the future leading to higher yields and the decline in the value of my bonds which says to me there’s more of a chance that bonds I invest in today wont be a good investment (the only reason i have them is to adhere to the principals of diversification). It seems to me better hold cash.

Nice intro to modern portfolio theory. The “I should buy gold then?” comment is perfect. The hindsight bias is just so powerful and obvious – If Andy Murray was a good tennis player last week then he’ll be a good tennis player this week… therefore if gold has been the best investment in the last few years it will be the best for the next few years (swap ‘gold’ for ‘dot com’ or ‘buy to let’ or ‘tulips’ as you see fit!).

I generally point people towards cash (or cash-heavy portfolios) unless they can prove that they’ll either leave their investments alone (i.e not chase returns) or that they have some half-decent inkling of what it really means to invest. The dangers of investing with only half and idea of what you’re doing are just too great (hence this series for beginners I suppose).

If this was way too basic for you this will be perfect.

http://www.efficientfrontier.com/ef/index.shtml

Speaking as a beginner, many thanks indeed for this article. I really, really wish this topic had been covered in school. Stumbling around in your 30s trying to figure it out is humiliating…

@Grand85 — With respect, you’re falling into the very trap I am talking about.

You are looking at the performance of bonds and seeing them going down for a year or so, and thinking they’re a bad investment. But what matters is (a) what they do over the long-term and (b) what they’re particular risks and rewards are and (c) what other assets you hold, and how they fare. (i.e. Your total portfolio).

Bonds aren’t in your portfolio to provide outsized returns. They are in there to provide modest returns most of the time, and stability at times of stress. Sometimes they will go down, perhaps for several years at a time, and this could well be one of those times. But we don’t *know* that and as Greg says they won’t fall as far as equities if they do.

In contrast, if shares fall 30% next year, you’ll be very glad you own bonds.

If you’re extremely risk tolerant and just want the highest chance of the best returns (but also the certainty of very bad years and the big risk, in the worst case, of missing your goals and losing most if not all of your money (in a Russia/China style situation)) then you should hold only shares, and small cap shares at that. Every take you step away from that towards safety (or from safety (cash) to risk) is a trade-off between risks and rewards.

Most people have no ability whatsoever to predict what asset classes will do in the short to medium term. I think we’d all agree I know at least a bit about investing, for instance, and I was wrong-footed by what I saw as a bond bubble way back in December 2008! It’s only in hindsight, with interest rates at 300-year lows, that it seems clear that bonds had further to rise back then.

All that said I happen to agree with you that cash can take the place of bonds for private investors currently, but it wouldn’t take much more of a fall in bond prices (and hence a rise in yields) for me to reverse that position. It’s an unusual situation. Cash, not bonds, is the safest asset class, because the principle doesn’t fluctuate, only the income (interest paid). But for that reason the returns are usually the lowest, and certainly lower than bonds.

At the end of the day, you have to decide if you’re a passive investor or an active investor. The latter will lose because they will make poor choices, sell winners, chase hot sectors, and so on. A passive investor will lose if they temporarily become active investors whenever a particular part of their portfolio is underperforming.

Remember, due to rebalancing you’ll be due to actually BUY MORE bonds in a year or so if this decline keeps up. But that’s fine, because shares will likely be well ahead in that case. (In my graph above bonds are down 3% but shares up 15%, so one would be over 10% ahead).

As a passive diversified investor, you will ALWAYS hold some of the worst asset class. And you will always hold some of the best. Currently the worst asset classes are government bonds, precious metals, and emerging markets. All have been the best in the past 3-5 years. Things go around.

Holding some of the worst investments is the price you pay for doing better than most investors who try to do better (and fail) by juggling stuff around. Just ask the myriad of hedge funds who’ve posted lousy returns since 2008.

Here’s a few articles on bonds we’ve written to read:

http://monevator.com/bond-price-falls-in-bond-market-crash/

http://monevator.com/sell-government-bond-funds/

http://monevator.com/how-much-will-bond-funds-fall-if-interest-rates-rise/

There’s loads more if you put “bonds” into the search bar in the right hand sidebar. 🙂

@TI

I have the bond articles booked marked and was going through them yesterday. I suppose this is the emotional side of investing, trying to rationalise making what appears to be a bad decision in the short term. However if something is for the long term one should supposedly pinch his nose and dive in according to his pre determined asset allocation.

Thanks as always.

Grand

@Grand — Yep, exactly. Some people think passive investing is easy. It’s not!

It’s simple. But it’s not easy. 🙂

So in the short term if you have no under-performers in your portfolio it most likely means you aren’t diversified enough?

@JJ, underperforming what?

@dearieme – The rest of the asset classes. For example the bonds that Grand85 is saying is a “drag” on his portfolio. I’m probably completely getting the wrong end of the stick. If you’ve chosen relatively uncorrelated asset classes and they are all doing well (or badly) it’s more likely you haven’t invested in enough asset classes than you just happen to have hit it lucky/unlucky?

“So in the short term if you have no under-performers in your portfolio it most likely means you aren’t diversified enough?” It means that you’ve been a great success at market timing but that now might be a good time to lock in some gains by deliberately diversifying. After all, you’ve not made a profit until you sell.

“If you’ve chosen relatively uncorrelated asset classes”; trouble is, you know only about their correlation in the past whereas you want to know it in the future. A different way to look at correlation is behind the Harry Browne Permanent Portfolio: he picks four sorts of financial eras and puts together a portfolio to protect your wealth from all of them.

http://www.getrichslowly.org/blog/2009/04/20/fail-safe-investing-harry-brownes-permanent-portfolio/

I like it as a recommendation from which you can begin to think about how you might adapt it to suit your purposes. For instance, when he first wrote there were no Index-Linked government bonds: there are now so maybe you’d replace part of the gold holding with some Index-Linked Gilts. And so on.

But there’s one problem with passive investing: when to start is an active decision. Here’s a comment I came across: “Diversifying asset classes, as Harry Browne knew well, can benefit a portfolio. The secret is deploying them before those diversifying assets shoot the lights out. Harry certainly did so by moving away from gold and into poorly performing stocks and bonds in the late 1970s. Sadly, this is the opposite of what the legions of new [Harry Browne Permanent Portfolio] adherents … have been doing recently, effectively increasing their allocations to red-hot long Treasuries and gold.” What the writer meant was that people were leaving cash and equities to buy bonds and gold with singular ill-timing. Mind you, he was writing in 2010, since when bonds and gold have done rather well – far better than he expected I imagine. And followers of the HBPP would have realised some of those gains when they rebalanced.

Here’s a link to a lengthy useful explanation of the HBPP.

http://earlyretirementextreme.com/wiki/index.php?title=Permanent_Portfolio

Much appreciated, thanks dearieme, I’ll give those links a good read. To be honest I’m still well over 80% in cash, I’m not jumping into any of this until I have done a good deal more studying and have a plan I fully understand.

@JJ — That’s an interesting way to put it, and for passive investors I suspect there’s a lot of truth in it. 🙂

Just to add to what @dearieme has written, I’d note that passive investors are usually best off rebalancing mechanically. That way you avoid emotion/misguided judgement clouding your decisions. Instead you reallocate back to your chosen asset allocation, and perhaps adjust as you age or your risk tolerance chances.

We’ve written a few articles on rebalancing your portfolio, which I’d suggest you give a read: http://monevator.com/series/how-to-rebalance-your-portfolio/

Finally, no shame whatsoever in being a newcomer to investing. Everyone is at some stage, and you’re going about learning the right way I’d say. Glad you liked the article.

Time and investments are a match made in heaven – but time and investors seem to be at a weary standoff most days. This is a great reminder that long term stability is always your focus, and not the emotional urge to dump an investment that’s a short-term underperformer.

Perhaps two final pieces of advice should be added for investment success

Live frugally

Save prodigiously

xxd09

“And as I write the Nikkei 225 is still far below its all-time high, more than 40 years later.”

Is it really more than 40 years since Dec 1989? How time flies! 😉

Or maybe you really do have that time machine?

@Marcus — Oops, thanks for spotting that. 🙂 It’s really even stupider than it seems because I had it at 30 years and changed it to 40 years in a final proofing, think I’d dodged a bullet! Doh! 🙁