Everyone assumes it won’t happen to them. But from history we know that not everybody is so lucky.

No, not jury service. I’m talking about sequence of returns risk. The unluckiest break that derails your financial future and throws cold water on your FIRE 1.

Sequence of returns risk is the risk of earning negative portfolio returns shortly before or after you retire. It’s a dangerous situation created when you start withdrawing money from a portfolio that’s seen little to no growth, only shrinkage.

Consider the following graphics from Axa Equitable [PDF].

The first charts the fortunes of three investors over three different time periods. All start with a $1 million portfolio that grows for 25 years.

Each investor experiences a different market cycle. But – neatly for the example – all three enjoy the same 6% average annual return:

The maths means the route doesn’t change the destination. With no withdrawals and the same average annual return, everyone ends up at the same place.

The maths means the route doesn’t change the destination. With no withdrawals and the same average annual return, everyone ends up at the same place.

But what about with withdrawals?

We assume the same investors start with $1 million each once again. They live through the same cycles as before. The average portfolio return is again 6%.

Déjà vu? Don’t worry, things are about to get interesting.

This time each investor withdraws $50,000 a year from their portfolio:

The difference is stark. The portfolio returns are the same. And Mr Green still leaves a fabulous $2.5m legacy.

The difference is stark. The portfolio returns are the same. And Mr Green still leaves a fabulous $2.5m legacy.

But now Mr Blue goes bankrupt!

Regularly taking money out of the portfolios vastly changed the outcome.

Mr Blue’s first three years of withdrawals coincided with a crash. He never recovered.

However the same three bad years came at the end for Mr Green. It scythed his portfolio, but it had already grown substantially by then.

That is sequence of returns risk.

A different mindset

Not selling as an accumulator is fairly easy. All crashes are buying opportunities with a long enough time horizon. Why not grab a bargain?

However a de-accumulator must – by definition – be taking money from their portfolio.

And sequence of returns risk means that a few early bad years for the markets – combined with withdrawals – can torpedo your long-term prospects.

Sure, even after an early bear market a decent portfolio should eventually start growing again.

But for an unlucky few, the damage is done. You’ll be a failure case. In 20 years or so you’ll run out of money.

You’re already dead. You just don’t know it yet.

SWR versus sequence of returns

Let’s not be too gloomy. The initial sustainable withdrawal rate (SWR) research was aimed squarely at these issues. It estimated how much you could spend while being confident (if not certain) that your portfolio would outlast you.

The data that fed into the SWR research included some truly dire periods. Depressions and wars.

Yet choose a low enough withdrawal rate and the data shows that – historically – everyone made it.

Even those those who retired into a bloodbath for shares!

However most people – especially early retirees – can’t withdraw a very low 2% a year. Their portfolios are too small.

Luckily you can ratchet SWRs up a lot and still hit 95% forecast success rates.

So most people do that. We assume we’ll withdraw around 4%, say, and 19 cycles out of 20 we’ll be okay.

In the good times we forget that means 5% weren’t okay. They failed. 2

The opposite is a fat streak. Your portfolio doubles, and doubles again. You spend with abandon. You leave your grandchildren a fortune. Those grandchildren tell everyone about their grandpa who retired at 50 and died rich. Someone writes an article about your investing smarts. Your portrait beams.

I hope that happens to us.

But this post is about avoiding joining the blighted failure cases – before it’s too late.

Retiring into a market that’s falling fast or an economy where high inflation threatens to savage your real returns?

Let’s consider your options.

Easy mode: watch but do nothing (yet)

Let’s say markets are down. A lot. But it’s not yet a long dream-crushing bear market.

Inflation may be stubbornly high. But it’s not yet an era of high inflation – let alone hyperinflation.

Should you act?

A good financial plan and asset allocation anticipates turbulence. Maybe you can grip the armrests tighter rather than parachuting at the first wobble.

Consider it a watching brief. Like when a suspect lump seems benign but your doctor says to keep an eye on it.

Most market upsets quickly pass and are soon forgotten. Look at Michael Batnick’s chart:

Source: The Irrelevant Investor

Not every investing herring turns out to be red – that’s the point of sequence of returns risk.

But depending on how you’d respond to a scare, it may be best to pause and ponder.

Pausing your plan

Reminder: if you’re in the saving and investing phase, keep at it. This post is not about putting everyday accumulation on hold. (Buy more shares in bear markets. You’ll end up richer.)

It’s only those drawing down their savings – or those getting close to the transition – who should consider acting if a bear market strikes, especially in the early years of retirement.

As we’ve just seen there are always worries in markets. Few threaten a solid retirement plan.

But some do. And it’s not obvious which ones in advance.

Consider 2020. It was a banner year for stock market returns. Spending fell so people saved more, too. Some people also got government assistance.

But we only know all that good stuff now. For much of the year people were frightened.

Who could fault somebody who retired in 2019 and panicked in March 2020?

Shares had cratered. A new illness was killing thousands. Governments were turning economies off. Many expected a global depression.

Personally I didn’t think it was the end of the world. But a threat to a new retiree’s long-term financial future? That was a far harder call.

So let’s be humble and pragmatic and consider some options.

Work one more year (or two)

Somebody has to say it. Maybe if a bear market is raging, keep working?

One more year is a curse in the FIRE community.

But truly bad periods for sequence of return risk are rare and damaging. Trying to avoid them is worth considering.

Stay employed longer due to a falling market and you won’t spend from a depleting portfolio. You could even add to it. Things should look better on the other side.

There are two snags.

Firstly, it may not be better on the other side. At least not anytime soon. Some bear markets last for years. What if you end up throwing several more years into the work furnace?

I’ve no idea how you’d feel. Some would-be retirees like their jobs. Some are killed by them.

But I know for sure you won’t get those years back.

Second snag: maybe it was a false alarm.

The good news is you’ll be richer when you do retire. But again you can’t get that time back.

Also you’re still exposed to sequence of return risk when you finally do retire. Albeit with more assets as a cushion after a year or two extra at work and some portfolio growth.

Go back to your old job

If you recently left work, you’ll never be more employable again.

Perhaps rewind the tape for a year or two if you’re having second thoughts.

Acquire more money

Sequence of returns risk hurts when you spend assets that have shrunk too far, too fast.

Continuing with employment avoids that. Instead of spending from the portfolio, you’ll save more.

But what if you can’t hack your job any longer?

Well there are other ways to get spending money.

Downsize your home

Many retirees plan to downsize someday. Where practical, bringing forward such plans can release cash to tide you through an early bad market.

If a stock market downturn coincides with a recession, downsize sooner rather than later if you’re going to do this.

Remember: you’re taking capital out of the property market. Not moving up the ladder. So do it when prices are buoyant to get the most cash.

Take a part-time job

Okay, so you can no longer stomach the nine to five to email before bed. But what about the ten to two? Or the Monday to Thursday?

A managed retreat from work keeps some money coming in for longer. Again, that could reduce or eliminate a fatal drawdown of your capital.

High-end information workers are blessed here. The word you’re looking for is ‘consultant’. Sweat that intellectual capital while you still have some!

Skilled tradespeople might transition to part-time pretty easily, too.

But middle-managers who owed their income to recently forfeited fiefdoms could struggle.

Enter the gig economy

The jury is out on the uber-flexible gig economy. Are today’s young workers getting a raw deal?

Maybe.

But for a workplace refugee in a bear market, the gig economy could be a lifeline.

Drive an Uber. Deliver for Deliveroo. Rent out a room on AirBnB. Whatever works for you.

It won’t be lucrative compared to your old salary. It probably doesn’t need to be.

I’ve explained before how just a little income is worth more than you think.

A few hours earning £100 a week equals £5,000-ish a year, ignoring taxes. You’d probably need over £100,000 in capital to generate the same income, depending on your SWR.

Spending your gig earnings to reduce your withdrawals could take the edge off a nasty sequence of returns.

Debt or other reserves

Now we get to what’s probably the least good option in the ‘mo money!’ category.

Best case: maybe you could hurry along an expected inheritance or some other bequest. There may even be taxes advantages.

Middling good/bad would be to drawdown cash from an offset mortgage. You’re taking on new debt, and increasing your monthly outgoings due to interest. Not ideal. (You’d also probably have to have arranged the offset mortgage years in advance while working. It may not be an option now.)

The benefit of releasing cash is your investment portfolio then requires less raiding for liquid spending money. Just remember to rebuild your offset mortgage pot ASAP when the markets bounce. (And acknowledge the risk that it might not bounce to your schedule.)

Beyond that are even worse options. Borrowing from family or friends. Raising cash on margin against your portfolio. (I wouldn’t, too risky). Equity release.

I’d cut my spending instead.

Tweak your investing strategy

Again, a market wobble isn’t unusual or necessarily an emergency. A good plan should be ready for rough patches.

Maybe you’ll spend a cash reserve first. Next you’ll sell your bonds. Equities last. They may even have bounced by the time you have to sell some.

Or perhaps you plan to live solely off portfolio income, and not sell your principal? Fine but this isn’t a free lunch. Inflation can outrun dividend growth for starters, and dividends can be cut. Though at least you’re not a forced seller of shares.

But however good your plan, as the German field marshal Moltke the Elder is often paraphrased: no plan survives contact with the enemy.

Or maybe you didn’t have a great plan anyway. With the market falling you see you were winging it. Or you were over-optimistic. Or maybe you’re less risk-tolerant than you thought.

Lower your sustainable withdrawal rate

What about a lower sustainable withdrawal rate? Success or failure can turn on small tweaks. Target 3.5% as your initial spend instead of 4% and you might never run out of money.

Consider a US investor spending $40,000 a year from a million dollar portfolio over 30 years. She would have have run out of money six times in 121 historical cycles, according to the FIRECalc tool:

However cut that withdrawal amount by just $3,000 to $37,000 and only one period saw a failure.

At $35,000 a year there were no failures.

Don’t get hung up on these specifics. This is historical data. The future is unknowable. The point is lowering your SWR by whatever you can manage will boost your chances.

Note that for long-term security you don’t just reduce your SWR during the early bearish years and then ramp it back up. The maths compounds from a lower spending base over a full retirement.

You were unlucky enough to retire into a market crash. So digest it and move on.

(Perhaps if the stock market gets truly euphoric you could reduce risk and readjust. But don’t rush!)

Take more risk

This is a bit counterintuitive and won’t work for most. But selling more of your safe assets to buy equities during a downturn should see you climb faster and higher on the other side.

Assuming you make it…

It won’t be easy. You’ll be taking stuffing out of your safety cushion to buy what’s reeking havoc. And you must have enough safe assets to spend your way through, so this is only an option for the wealthy. There are no guarantees it will work either – especially not quickly.

I could imagine doing this, but that’s after a lifetime of very active investing. Most should consider other options.

Take a bit less risk

You wanted a feature-rich retirement. You also wanted to leave a chunky legacy. The sun was shining and markets were flying.

So you exited the workforce with an aggressive portfolio – 80% in equities.

The first Monday out of work shares fell. By the end of the week they’re off 10%.

You panic.

There’s no shame in learning your true risk tolerance later than is ideal. It’s better than denial. Investing when you have a regular salary is very different to shepherding a pot of worldly wealth.

You are where you are.

Now, nobody wants to sell when markets are down. You’re locking in losses.

But it’s better to take limited action when shares are 10% off than to capitulate after a 50% decline.

If you’re rich enough, consider swapping shares for cash and bonds until you feel comfortable again. Do not abandon shares completely. Nearly all of us need some equities to meet our portfolio goals. But try to immunise yourself against freaking out at further falls.

(Then maybe turn off the stock market news.)

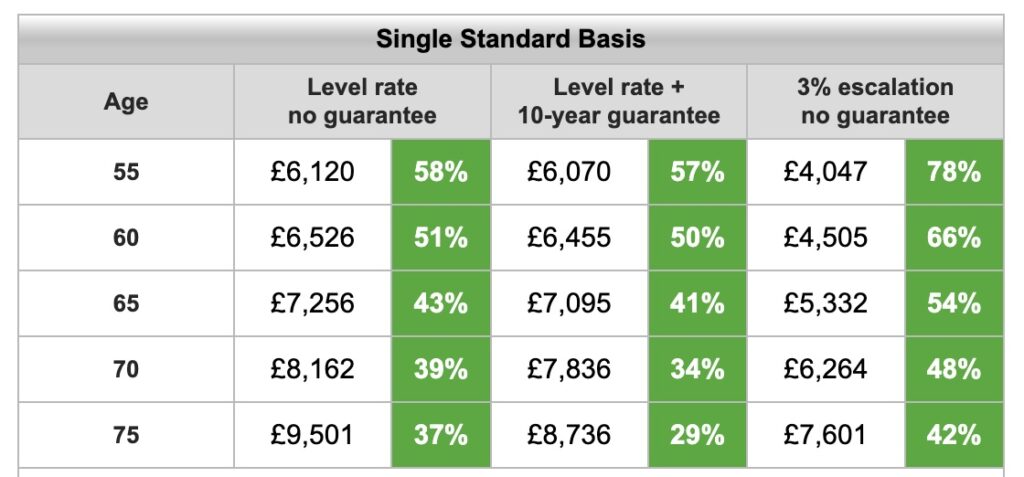

It might also be worth looking at an annuity. Especially if you’re a not-so-early retiree.

Annuities can provide a low but very safe floor to your income drawdown strategy. That’s valuable.

What not to do

Don’t punt on cryptocurrencies or buy NFTs to make good your losses. Don’t bet at the races.

I’m also not talking about tactically selling your shares, hoping to repurchase them when the falls are done and the sequence of returns turns to your advantage.

If you could be confident of making that operation work you’d already know it. You probably can’t.

More likely you’ll lock in losses and then miss the rebound. Maybe you’ll spend years waiting for a second bite. Your entire strategy is now derailed.

Market timing will cost most people more than they ever make. It’ll also turn your hair grey.

Cut your spending

Your wealth is down. Your portfolio is shrinking. But you need income from it to get by.

So spend less money and then you’ll need less of an income.

If you’re a fancy sort, you’re adopting a tactical withdrawal strategy, dontyaknow.

If you’re a simpler soul like moi, you’ll cancel your foreign holiday, put off buying a new laptop, and rediscover your inner graduate student.

Live well but cheaply until the tough times pass. It’s not so hard. (Especially if you own your home).

There are innumerable ways to reduce your outgoings. Doing so probably got you here.

Just remember retirement spending is a thorny problem not simply due to the risk of running out of money. There’s also the ‘danger’ of leaving lots of leftover money at the cemetery gates.

Because sequence of returns risk cannot ever be known perfectly, you may be making unnecessary sacrifices. Some postponed opportunities (travel, say) will eventually recede completely.

Many retirement plans assume your pot will go to nowt. If your plan does, get used to it.

The ideas in this article aim to reduce the risk of accelerating the march to zero due to an unlucky early knock. The aim is not to abandon your plan whenever your portfolio wobbles a few percent.

Down but not out

If you’re vulnerable to sequence of return risk when a bear market strikes – newly-retired, smaller portfolio, early exit from work, few other resources – I’d consider acting to protect your future.

By pick-and-mixing a few evasive measures, you could reduce your exposure to sequence of returns risk without too much pain, even if your portfolio has been shellacked.

For example you could reduce your long-term SWR by 0.25%, work a day a week, and swap one meal out a month in your budget for an M&S Meal Deal.

Perhaps that would make all the difference?

This is not an exact science. That’s why I haven’t bothered with spurious calculations in this article.

Nobody knows the future.

A bad market can turn on a dime. Perhaps you’d have been fine, after all.

Rather it’s all about risk reduction.

If today’s crash is tomorrow’s false alarm, no harm done. You’re better-placed going forward. You can enjoy swankier remaining years than you’d originally planned for.

Conversely if it’s not a false alarm, you’ll be glad you did something early.

Better safe than sorry.

Comments on this entry are closed.

I think you missed one option here: If there is a make-or-break risk that you can’t diversify away on your own, you can insure against it. I know it might not be in the DIY nature, but an annuity that trades a small hit in withdrawal rate for guaranteed security can make you sleep a lot easier than the prospect of having to move because of a market downturn, or running SWR calculations even while senile.

@niwax — I mention annuities in the article.

Well, thank you very much for this timely post!

@TI – great article. As ever!

I’d been planning on retiring this April all last year. But…

I shouldn’t really worry as my wife will keep working for another decade. In extremis, she can keep us all comfortably. The deal is I’ll contribute 1/3 to the family budget until my pensions kick in when I’ll contribute all. In both scenarios the withdrawal rate is 3% and leaves me plenty of “beer money”. But…

Anyway, Boris has cured Covid so we’re off on hols. Driving through France to Spain. If the petrol’s not rationed… And we can afford it… I’ll make a decision then. Maybe.

maybe you could hurry along an expected inheritance….

Mmmm that can’t be legal.

Having worked for myself for the last twenty five years I’ve got quite used to a fluctuating salary. I’ll be telling my wife the reason she can’t have a new car is because we are following a tactical withdrawal strategy.

When I think about the original 4% SWR paper it seems one of the flaws was it was looking for too much certainty. The whole idea that you can start at a set percentage and then increase by the rate of inflation every year. I don’t think many people used to the modern world of work would have that expectation.

Introducing addition to a multiplicative sequence smells fishy to me.

I still think a bucket fund approach with equities/bonds and 2 years of cash is another good option. Most crashes (ok not all but most) recover within 2 years. This would still leave your bonds pot as a further source of withdrawal if needed. All without touching your equities pot. Simples.

One nice risk management tool is the addition of one or two state pensions, which can be deferred.

You can then deplete if you know that there’s a decent floor.

You can also buy a small annuity with some of your (presumably DC) funds, if the SP / deferred SP doesn’t give enough of a floor.

There’s also Equity Release as an option, albeit tread with caution.

Finally it’s also a bit simplistic to assume linear spending in retirement.

My broad aim, from the comfort of a couple of years ahead of pulling the pin, is to have a steady depletion between 55 and 67, when 2 x SP will kick in. I’d rather do this than a steady 4% and suddenly get a large uplift part way into retirement.

Either way, I’ll stay alert and flexible, and adjust micro and macro as the market ebbs and wanes. I recognise I have the great luxury of great flexibility above the “essential expenditure” base level.

Fantastic article once again, so important to be aware of the risks and the array of options you outlined so well to navigate through them. Thank you.

100% agree with ex pat scot. It seems to me that a lot of the predicted outcomes assume a fixed expenditure throughout retirement, which I don’t think is correct. I fully expect to be spending less in my late 80s onwards than I will in my late 60s.Also there is the state pension to consider which, whilst not being enough to live on, will provide a reasonable baseline and reduce the amount of drawdown required. Also a lot of American predictions show increased expenditure in later life, but this has a lot to do with their insurance based healthcare system

Very comprehensive @TI but maybe worth including a link to @TA’s Decumulation plan? https://monevator.com/decumulation-a-real-life-plan/

For me, I think the three most effective tools my wife and I will have to counter SoR will be (1) dynamic asset allocation (including three year cash buffer) as you describe to avoid selling equities when they are down, (2) a flexible withdrawal rule (based upon CAPE) I have modified this and if required (e.g. after “bad” SoR) I plan to change our constant adjustment figure at 67 (to allow for the state pension) and (3) additional income (we don’t plan to downsize) but we will move (Camel Estuary 😉 and hopefully rent out an annex.

There was a good suggestion in the comments on this site a few months’ back, which was to ensure that you’ve got any potentially big expenditure out the way (or funded in cash) before stopping work – e.g. fixing the roof, getting new kitchen appliances, maybe a more reliable car or whatever. I guess it may mean working a bit longer to get that done, but it’ll mean more flexibility with drawing down income during the early years.

P.S. Should be “wreaking” havoc (unless a pun was intended).

I tend to agree with the notion of having a cash buffer of a few years of expenditure. Sure, it’ll be getting eaten by inflation, but you’ll won’t have to touch your other assets. You can go further, through bulk buying dry goods etc. Part of my reason for buying solar panels was as a hedge against future energy costs.

Belt tightening obviously has a role too as does selling off stuff you own that falls into the nice to own, but not essential category. I’ve known people who’ve bumbled along for years through buying and selling stuff, doing the odd job for someone etc. They are never rich, but they have a lot of free time for their hobbies.

No one seems to talk about using Target dated retirement funds during drawdown phase, but don’t they mitigate this very risk? Whilst they do have a low equity percentage in those years, and any withdrawals do come out from both the equity and bond components of the fund, you would hope that in bad times for stock market, they will be rebalanced back to the same equity percentages as specified, meaning that any net withdrawals are skewed towards bonds.

Yeah, I think the main ‘benefit’ of such funds is the simplicity; I could recommend these (in a non-expert/unqualified way) to my family as a good simple sipp/isa fund and know for the zero subsequent effort involved, if that was the only fund they invested in it probably would do reasonably well and if it went down a lot, the chances are the whole marker would be down so no blame or grief would come my way for the friendly chat/’advice’. Such family members would not be trying to FIRE and simply trusting of getting fairly simple and understandable options from someone who they knew had no financial interest in whatever they then decide to go on to invest in.

The problem is also this simplicity… for people genuinely putting the work in to retire early, they will understand the risks and options better. It may be the case they would have done better with the lifestrategy/target date type funds, but once you are seriously looking at retirement planning especially at earlier ages, even the most humble index investor will be thinking about their options and risk tolerances. I am in this category, with a 50% bond (mostly government and short term quality bonds), 50% equity split, all passive funds, with slightly off-world equity country proportions by using continent type index funds (to avoid ~70% US + Canada exposure which I believe is too high, even if I know about efficient markets and all such things).

I am down in bonds at the moment, and some equity funds have taken big hits. To me, this is fine, the worst historical single year bond return I could live with, whereas the worst single year return in equities would keep me up at night worrying if I was mostly equities. I now get to invest new money to bring my overall position back to normal, which means buying more cheaper equity index funds in the regions with heaviest losses.

Would I be better off with a vanguard target retirement date funds? Quite possibly, but even after non-negligible bond losses and some equities taking a big hit in my investments, I basically think ‘whatever’. I also know if US equities tank for whatever reason my equities wont be obliterated overnight. I accept normal world indexing approaches and even target retirement funds would likely get me to the same end point and possibly faster, but short of a huge worldwide economic collapse where everyone is in danger, in any hurrendous year I am likely to be down by about 30% max (e.g. if world equities lost 50% in a year and bonds 10% in a hurrendous year, my investments would only be down about 30% overall). Given my initial investments each year are in work pension > small-ish SIPP contributions > LISA > S&S ISA then a few years of cash I keep in rolling 1 year fixed term savings, a large proportion of the money I invest is tax favourable inputs so might only have ‘cost’ me £60-70 for each £100 I invest iny pensions+ISAs. Basically, a disastrous year of returns leading to a ~30% loss would barely take away the tax savings and employer matches from my pension+LISA contributions etc. This thought process dictates my equity/bond splits and why I avoid single funds such as target dates.

Despite all this, if my brother asked me for friendly input to do minimal investing that was low effort, I probably would say either a 40% or 60% equities Vanguard, or a target retirement fund if it was genuine pension savings. The return would probably be as good or even better than mine in most normal times. Your question is more difficult at the stage you are spending the funds, since automated changes from bonds to equities or vice versa could lead to bad luck with the timing of rebalancing. Indeed, my main problem with funds is the delay in selling – at the point you are selling funds having the guaranteed sell price without day(s) of delay to get an unknown price per unit is far from ideal. As an investor still, I only rebalance with new money or rebalance by selling high funds only when respective indexes are at new, or near, all time highs. In drawdown I won’t be as picky, but having the sell price known in advance becomes more important, even with the dealing charges involved.

Just for info, I am not extremely high earning, never making it into the 41% tax band, but investing in a way that to me minimises the potential for huge losses over short periods means I need to aboid single target type funds – most have too high equities FOR ME, and too much US exposure for me.

So, despite target funds and true world indexing being somewhat optimal and good/safe enough to recommend and use, once you are really serious about early retirement and think enough about your options and risk tolerance, you might want a little more control with more than one fund, even if you know that you may be reducing your expected returns in the process.

Spot on time for me on this one @TI

The plans are coming together and me and Mr McClung are good acquaintances now. (I hope). As I said at the beginning of the year I am cash heavy until about now by necessity. (this sheltered me a little from a 7% drop to date this year in the stocks and shares side so not too bad yet and holding steady)

I still believe I will retire exactly when I intend this year (the holiday has been booked for some time now) and my SWR was always on the conservative side of 4% (McClung actually persuaded me to meet him half way with it and up it slightly)

My biggest concern is what to do with the cash when it gets released from its ties now? Another risk calculation to do

Thanks again for this. Been very busy the last few months so it has taken my mind off a lot of other things such as Covid and war and money. Pehaps this was a blessing.

JimJim

Great article with some various useful tips. Sequence of returns risk is an absolute ******* to have to deal with but is something we have been extraordinarily luck with since we retired.

For those advocating a cash buffer to use when markets are down, this always sounds great, but you need to nail down when you will draw from it instead of drawing from your investment portfolio, when you stop using the cash buffer and how you replenish it.

For what its worth, we have a hybrid approach. We keep up to 6 years projected spending in cash and spend from it, but we top up the buffer from dividends regardless of the level of the market*. In other words we intend to continue drawing from the investment portfolio even when markets are down. We also top up the cash buffer from asset disposals when the value of the investment portfolio exceeds 60 years worth of income.

When the cash buffer goes above 6 years income we give away and/or spend the excess. This is our way of putting a lid on the eventual IHT bill. Others might prefer to just reinvest and perhaps ratchet up the spending or reduce the SWR, or both.

Asset allocation in the investment portfolio is straightforward – 100% equities spread across multiple ETFs and tracker funds, weighted according to the FTSE World Index. Plus a few oddballs which with the benefit of hindsight would have best been avoided (US REITS, a US min vol ETF, small cap tracker ETFs).

* Drawing dividends from the portfolio when the market is down is definitely something I have mixed feelings about, but my wife made up our minds on that one.

@naeclue

Thanks, I like your plan – a few questions if you don’t mind:

1- is there a FS pension and state pension underpinning any of this approach?

1a – the 100% equities feels bold, but if you have ~(60+6)x spending then it does allow some risk/freedom

2- I currently have 4x spending as cash and it feels a lot. Are you tempted to invest some of it when the market dips significantly?

Rightly or wrongly I’m quite keen on dividends to fund spending, without needing to sell – it just feels less stressful and more predictable

B

@TI:

Great post; ERNs latest post on “using“ leverage against SoRR may be of some interest.

@naeclue:

Thanks for the update on your strategy. OOI what do/would you do with share buy-backs and similar?

@Boltt, State Pensions do form part of the plan, but we are not old enough to draw them yet. We hold additional cash deposits to bridge the gap – not enough with current inflation rates!

I don’t think 100% equities is particularly bold in our case. 6y cash + 60y equities can be thought of as 6y cash + 34y equities, similar to a 15/85 bond/equities portfolio, with a SWR of 2.5%, which is probably all we need. Plus we have a “spare” 20y equities portfolio as plan B. In addition we will receive full state pensions and my wife has a small (about £2k per year) DB pension. Plan C is that we have a holiday home we could let or sell and at some point are likely to downsize our main home.

Yes 6y spending does seem a lot but we don’t hold bonds any more and no, we have no plans to buy any more equities – a strategy borrowed from McClung. So far I have not been tempted, but an article by Wade Pfau, linked to on Monevator recently, got my interest. It suggested borrowing to get through a period of poor market returns. So perhaps 3-4y cash, with the intention of borrowing 2-3 more years in tough markets might be more efficient? Still thinking on that.

Dividends can be deceptive, but what you have to remember is every dividend paid is made at the expense of the value of your portfolio. A company declares a 1p per share dividend and 1p per share comes off the value of your shares on ex-dividend date. Taking dividends out when the stock market is down is just as bad as selling shares when the stock market is down, which is why I have mixed feelings about doing it.

The good thing about dividends is that they come free of all trading frictions, assuming you don’t reinvest. In theory that is. In our case we sell shares outside tax shelters and buy back inside in order to “liberate” those dividends. One day that should stop though and we should simply be able to withdraw the dividends from the tax shelters.

@Al Cam, share buy-backs and other corporate actions are things I don’t have to concern myself with as I only invest in ETFs and tracker funds. If I was faced with them I would probably do my best to ignore them. Rights issues would be tricky.

The thing about dividends is the money gets given to you without any frictions, except maybe currency exchange fees on ETF dividends. No trading fees, no risk of anyone front running your trades or having to suffer bid/ask spreads. I absolutely would not load up with high yielding share funds though in order to increase the dividends. The additional costs and long term risk of under performance would not justify the benefits.

Thanks for the tip on ERNs post. I will check this out.

@naeclue:

Re: buy-backs, etc

I think the process for accumulating etf’s/funds is probably pretty clear. However, l suspect things might be more nuanced for the distributing versions, and, for example, the distributions may comprise more than just “pure dividends”. What do you think?

Use a “data driven” approach towards “income stage” investing and income withdrawal.

Research shows that a portfolio / index representative of the Large cap “value” universe has sustained between a “3.5% – 7%” inflation adjusted annual withdrawal rate ( “sale of shares”, dividends reinvested ), accompanied by terminal portfolio growth, over seventy one rolling 20 year periods and sixty two rolling 30 year periods since 1931 ( study link https://tinyurl.com/y6key3v5 ) .

Digging deeper, while over the course of the year the market can move in all sorts of directions, the time frame that is most relevant to a large cap value income investor, is the last few days of the year. As described in the study link, this is when the investor compares their portfolio balance to their initial portfolio balance value when their “withdrawal stage” commenced ( see “90% balance rule” ). From there, they can make a simple determination as to what percent ( 3.5% or 7% ) income that they can withdraw from the portfolio for the upcoming year’s spending and budgeting needs.

Historical evidence shows that an investor has been able to take an average 6.5% or greater inflation adjusted income withdrawal off of a large cap value portfolio, accompanied by terminal growth, over 90% of rolling 30 year periods tested since 1931 ( see “All 30 yr withdrawal periods” tab https://tinyurl.com/34xf7pkb ). And this income stream survived World Wars, recessions, a myriad of geopolitical and economic environments, pandemic?, etc.

Therefore, one doesn’t have to “wing it” or even “guess” as to what withdrawal rate to choose.

@James — Thanks for the comment and data, interesting. Ultimately though it’s a bet on factors (the large cap value factor) and whether that will hold in the future. I wonder indeed where that paper would have been had the result run until end of 2021 instead of 2019, given the massive under-performance of value?

There is a credible argument that all factors / anomalies are just that (anomalies):

https://monevator.com/why-invest-in-alternatively-weighted-index-tracker-funds/

Even if not, factors can go into drawdown over multi-year periods that may look fine in a backtest but are hairy in real-life! Imagine waiting 15+ years for large cap value to come back into vogue as a pensioner…

As mentioned in the article market-cap vanilla exposure to US stocks has certainly had failure periods with SWRs as low as 4% (see FIRECalc in the article).

To be clear I’m not saying large cap value is a bad way to go, or discrediting the paper.

I am saying future returns are always uncertain. But of course we have to find our own way to live with and accommodate that reality.

@James, thanks for link. In addition to @TI’s comments, my immediate reactions when it comes to research like this on drawdown, identifying a winning portfolio and strategy, are 1) to ask the question “How likely is it that the positive outcomes are not a result of overfitting and cherry picking?” and 2) to point out that an “average” SWR of 6.5% does not really cut it – what does the distribution look like and what was the minimum SWR?

To expand a bit on my overfitting/cherry picking question, in answer to the question “Can I construct a portfolio of equities, bonds, gold, etc. that would have given a 100% success rate, with 100 years of historical data, drawing down at an average 6.5% SWR for 30 years?” The answer is undoubtedly yes. You have identified one such portfolio and strategy, involving US large cap equities. There are undoubtedly other approaches that would also have worked and many that would not have. What confidence do I have that the historically successful portfolios/strategies that are out there will work in future, producing a similar distribution of outcomes?

If I analyse previous winning lottery ticket numbers, I am sure I would be able to come up with a formula/algorithm that gave a better than average chance of picking winning numbers within the historical data. Assuming the lottery was fair, it would be absurd to expect that algorithm to work in future. To what extent is any proposed portfolio/strategy not similar to a winning lottery ticket strategy?

When it comes to factor research, the difficulty I always come back to is the question “Why would today’s market participants not learn from their predecessors’ mistakes?” eg US large cap equities were under-priced. Everyone knows that, but given that everyone recognizes the historical under-pricing, why would they continue to be under-priced? Risk and/or psychology are the answers offered, but I am still unconvinced the extra expense of investing in factors will be compensated with higher returns. My experience to date does not help as I picked the wrong factors – I would have been better off investing in lower cost cap weighted trackers.

@Al Cam, “the distributions may comprise more than just “pure dividends”. What do you think?”

They do! Just to give one example that affected me, I got a huge dividend in 2014 from Vanguard’s FTSE 100 ETF, VUKE. Something like 5 to 6 times more than I was expecting and I had to pay higher rate tax on it. It turns out that the high dividend came from the corporate action involving the demerger of Verizon from Vodafone. Clearly not income, but Vanguard chose to dispose of the shares and pay the money out as a dividend. iShares, in their FTSE 100 ETF, chose to reinvest the proceeds which I think was the more appropriate thing to do.

Lessen learned – ETFs seek to replicate the total return of an index, NOT to replicate the ex-dividend index and pay out all dividends. They clearly have some discretion over what gets included in dividend payments.

@Naeclue(#26):

Thanks for that.

Pretty much as I thought – but I was struggling to find anything definitive. Your example is an excellent case in point of the nuances present in distributing versions of etfˋs/funds!

I suspect that may be why they use the term “distributing” rather than dividends in the product descriptions.

@Naeclue (26) Thanks for that insight on VUKE. I bought this ETF in early 2014 and never did understand why my first dividend was so large or, for that matter, why the value remained below the price I paid for it for so long!

@Al Cam, I think the word distributions is used at times, but dividends are taxed differently to interest distributions or capital distributions so Dividends have a specific meaning as far as tax is concerned. I hold some US listed ETFs that have in the past made capital distributions, but have not yet had to face that situation outside tax shelters.

I guess it would be possible for ETFs to take their fees and other costs from capital instead of income. Some ITs and actively managed funds do that.

The more I think I think about this, the more I am inclined to think our drawing of dividends is illogical. If we were annually rebalancing between cash and equities it would not really matter, but our “sell only” approach to equities inevitably leads to drawing dividends following a market crash. Not ideal.

@Naeclue (#29):

As usual, the devil is in the (plethora of) details, including the fund, the tax rules, etc and – just to add to the fun – common words may not, of course, have common meanings. Yikes!

That’s a really interesting article TI, thanks.

I myself am fairly risk averse with all of this and for that reason, I no longer have a set date or definite year I will possibly retire. I aim to be FIRE ready at 50 loosely with £24k 4% (£600k pot). I intend to secure a safety net guaranteed income at pension age perhaps 18-20 years later via state and a public pension more or less matching £24k a year, this includes owning my own property.

I therefore could accept but no doubt it would hurt if my money ran out by or before pension age. I would simply spend less as I have a buffer in the £24k so there is wiggle room in a market downturn, like you say I would have less holidays or put off the new iPad Pro purchase. I also reserve the right and possibility of getting a part time job and might carry on working as I enjoy my job (currently at least) but I have to be realistic and an inheritance is also likely during 50-70 to help cushion this also.

I would feel far too panicked myself and wouldn’t sleep at night if I had a monthly withdrawal with no wiggle room buffer and that I needed to last 20-40 years with no safety net…

TFJ

Thanks for the interesting fact filled article.

I was fortunate to RE at the age of 37. About 7 years prior I had stumbled on the ERE website and the journey began. We re-sized and simplified our lifestyle to save typically 50% of our after tax income and invested the lot in funds whilst contributing to workplace pensions (permanent portfolio approach).

On FI our family made some big changes, the major one was leaving the UK for the South of France due to the reduction in living costs.

What was always difficult to calculate / estimate was the living cost in France and the need to consider exchange rate risk. Yet this turned out to be a positive surprise as we to a small degree overestimated our living costs, that formed the basis of our FIRE buffers and calculations.

As an example we bought a rundown property (very cheap vs UK – no mortgage required) did a lot of the renovation ourselves. We installed wood heating (the price of wood does not vary dramatically YOY, it is a cheaper heating source but requires moving wood around / we can grow and harvest some on our our own / it is messy etc.). We have free fruit from the grounds and any vegetables grow easily. Outdoor markets are cheap. Other costs such as transport, clothing and taxes have dropped dramatically as work related needs and income dropped. Holidays are on our doorstep and can be very cheap if you go camping (especially with kids in tow).

We have a diversified income with dividends (large cap growth) along with some real estate until we have access to our private pensions. My wife has a small side hustle to top up the coffers and for some treats.

The one thing I would probably re-think is pensions – the money is tied up. If you want to FI as fast as possible why bother with a pension (just an ISA?)….. I have done a lot of sums, to me it seems like a throw of the dice, and worth consideration based on individual circumstances.

Good luck

Very practical article.

Thank you @TI.

Re “What not to do”: I know this sounds overcomplicated but bear with me.

Say (like I am, more or less) you’re 100% equities and say you’re coming into retirement (about a decade to go for me).

You decide – I can’t take this risk but I don’t want to forgo the asymmetric return equities can (perhaps) bring (from time to time).

So, you sell and go to cash/ MMF/ cash like instruments (short duration gilts etc) and then you’d use a small (5%) portion of the proceeds to buy a long dated (LEAPS) OTM call on the index tracker (VWRL say) and, at the same time, sell a put on VWRL with a nominal value equal to the remaining amount (after drawdowns) of the cash proceeds of selling your equities, with a strike price set at a level where you’d be happy to be buyer of the index (because shares would represent better value, and less risk of holding).

Market then rises or fall, but not enough to hit either the call or put strike and you collect the put premium and forgo the call premium.

Markets hit call strike, but not the put, and you make a profit on the call and keep the put sale premium.

Markets hit put strike but not call and you have to use the sale proceeds of cashing out of equities to buy VWRL at the put strike, but you’d be happy to own the index at that price anyway. You just lose the call premium (say 5%).

If somehow the call and put strikes are both sequentially reached (say by a crash followed by mega rally or vice versa), then you both get to profit from the call and buy the index at the put strike, being a price you’d be happy to be buying the index at anyway.

As a decumulator you’d have addressed the risk of a loss of capital value in the first years of retirement.

But what have I missed here? It seems to good to be true?