A fabulously articulate and doubtless physically attractive Monevator reader (yes, I’m a fan of all our readers!) emailed to ask why invest in bonds, given the superior returns from shares.

He spoke thus:

It’s financial orthodoxy that bonds should form part of everyone’s portfolio. Equations abound, such as “hold a percentage of equities equal to 100 minus your age”.

I do understand that bonds are crucial for people forced to live off income, such as retirees.

However the other reason frequently given for holding bonds is to ‘reduce volatility’.

I’ve always failed to understand the logic of this argument. As long as you have a long investment horizon, then volatility should not affect your investment. Prices rise and fall, and the value of portfolios do likewise.

As long as there is no need to sell, however, then it makes no difference.

Given that equities have historically outperformed bonds, I wonder why anyone in their 20s or 30s would hold any bonds whatsoever?

Or am I missing something?

This blog has the smartest readers. You guys ask all the right questions.

I can’t reply in detail to the many emails we get each week – and I can’t give personal advice at all – but it’s always great to hear from you. As also shown in your comments on the site, you’re an above averagely clever cohort. (Heck, we even know what “cohort” means around here. Go us!)

Onto this query, which I’ve heard quite a lot recently, especially with the rise of Vanguard’s automatically rebalancing LifeStrategy equity/bond funds.

I should first say that asking me why invest in bonds is a bit like asking Worzel Gummidge why shower. I’m skeptical about corporate bonds, and while I do think government bonds have a role to play for most people, I usually hold none myself.

I do understand though why nearly all model portfolios include a slug of government bonds. So hopefully I can give a rounded answer without spouting too much ‘financial orthodoxy’, as our reader puts it.

Below are seven reasons why bonds – UK government bonds – might earn a place in a portfolio, despite the superior prospects of a 100% equity portfolio.

Note that I’m not debating here whether bonds look good or bad value right now. We’ve covered that elsewhere. (Executive summary: They look expensive to me).

Government bonds are the safest asset class after cash

Ignore the ranting of the lunatic fringe 1 – for the UK investor, UK government bonds (aka gilts) are the closest thing to a risk-free asset class, after cash.

Safe here means “return of capital” not “return on capital”.

Since 1950, UK bonds have delivered an after-inflation return of 2%, versus about 7% for UK equities. 2 2% is not a huge margin of safety. If inflation is higher than expected, the real return from bonds could be closer to zero, or even negative.

But no investment is entirely risk free, and inflation aside, gilts are safe.

There is a near-zero chance of the UK not honoring its bond commitments, because it can print the money to do so. When you buy gilts, therefore, you can be extremely confident of the return you’ll get from the interest paid plus the return of capital. That’s attractive compared to the uncertainty of every other asset class.

You can even sidestep the inflation risk if you buy index-linked government bonds or TIPS in the US. (Like other government bonds, they’re currently priced for very little return though).

Volatility can be scarier than you think

Most people believe they can cope with volatility. However when confronted with their net worth plunging 5% in a day, 20% in a month, or 50% in a decade, they often change their tune.

The speed with which a bear market can slash the value of shares is proof positive that many investors panic when times turn tough – because their dumping of shares is exactly what drives the prices down.

Government bonds tend to go up – or at least better hold their value – when share prices fall. They also pay an income. Both factors curb the decline in your portfolio’s value when shares plunge. This silver lining can make stock market falls less terrifying. There’s nothing irrational about wanting some security.

By all means steel yourself to ride out volatility. That’s what I do. It’s easier if you’re young, and much easier if you’ve got substantial new money coming in from savings.

But you won’t know for sure how you’ll cope with extreme market falls until you’ve lived through them. Even after that, you might react differently at 60 when most of your lifetime savings are at risk, compared to how you did at 30.

Most people are much more risk-averse than they think. Why be a hero?

Diversification with a slug of bonds is cheap and effective

If shares do better than bonds – and they always have in the UK market over two decades or more – then a 100% equity portfolio will beat the returns of a portfolio that includes bonds alongside shares.

However adding in even a small allocation of bonds can reduce the maximum losses you’ll suffer in a bad year without significantly decreasing your overall return.

Without getting bogged down in financial theory, it’s all about the ‘efficient frontier’, which is the point where diversification is actually reducing risk while maintaining returns.

The following graph shows how portfolio theory suggests risk (volatility) and return will change as you shift your allocation between equities and bonds.

Diversification is the only free lunch in investing, and bonds are on the menu.

Of course, you can’t eat theory. What about real world results?

Well, you can use different time periods to make pretty much any point in investing. However this example data covering a 20-year period in the US markets between 1988 and 2008 is pretty typical:

- A 100% US equity portfolio returned on average 11.59% a year over the 20 years. The worst year saw a decline of 20.25%.

- A portfolio with a 55% allocation to bonds and the rest in shares returned on average 9.95% a year. It fell a mere 3.35% in the worst year.

Many people would have lost sleep and hair enduring the 20% decline in the all-equity portfolio, even if they managed to stay invested.

In contrast, I think even the flightiest saver could stomach the minus 3% worst-case year of the bond heavy portfolio.

Yet despite the massive allocation of bonds required to produce that low downside risk, the ultimate price paid – the reduction in return – was less than 2% per year. Painful when compounded for sure, but not fatal.

Now, get pinching your salt. This particular 20-year period saw a boom for bonds. Their returns were unusually high, due to a collapse in yields that cannot be repeated.

But we only know this from hindsight. Also, if your shares do much better than bonds in the future, then you probably won’t care too much, as long as you’re not too bond heavy. Even the worst case for bonds – a full-on bond market crash – will likely be milder than a stock market crash.

For the avoidance of doubt, I’m not advocating a 55% allocation to bonds. This is just example data; personally I’d lean to less is more. Check out these model passive portfolios for some expert ideas on asset allocation.

But remember, sensible investing is not about aiming for the maximum return that’s possible over the period you happen to be invested. That’s the siren call of City promoters. It’s the thinking that got people loading up on tech shares in 1999, and giving up in the depths of 2008.

Your aim when investing is to devise a strategy that works for you, and that you can stick with.

Lower than maximum returns is a price worth paying if it keeps you happily investing for your lifetime.

The outperformance of shares in the past may not continue

This brings us to returns, and the implicit assumption that shares will always do much better than bonds over the long-term.

In the UK and US that’s been true. But a look at the long-term returns from other stock markets around the world shows the degree of outperformance of shares over bonds has varied, even over the extremely long-term.

Over the short to medium term, anything can happen.

Japanese investors in the Tokyo stock market – who are still down 75% from the Nikkei’s peak of the late 1980s – might offer an especially salty rebuttal to anyone urging an all-equity portfolio.

There are strong theoretical reasons why shares should do better than bonds (it’s all about risk and reward). And I’m literally betting my own asset allocation on it, with bonds seeming to me to be at the end of a bull market and the returns of the past three decades mathematically unrepeatable from here.

But there are no guarantees.

A holding of bonds enables you to rebalance effectively

We know from Warren Buffett that we should “be greedy when others are fearful” when faced with bombed-out stock markets.

But where are you meant to get the cash to go on a buying spree?

Buffett himself urges investors to stay invested in great companies through thick and thin.

Sage advice no doubt, but if you’re 100% invested in shares when the market crashes, you’ll have to limit your being greedy to going to pizza joints in the City to scoff at worried bankers.

In contrast, if you’ve got a slug of bonds you can sell them down to stock up on cheap shares, either haphazardly or through a more formal rebalancing strategy.

As you age, you’ve less time to recover from crashes

Like many things, the answer to our reader’s query is in his question. He says we’re assuming a long-term horizon, but the fact is not everyone has that – and none of us have an infinite one.

As mentioned, the Japanese market peaked in 1989. Even the FTSE 100’s peak was 13 long years ago. If you were 60 in 1999 and you were 100% invested in shares, you took a big gamble.

Focusing on income can offset some of the risk of volatile share prices. Dividends are much less variable, and the UK’s best income investment trusts have not cut their payouts in the bad times, while handily beating inflation over the long-term. A high yield portfolio might deliver something similar for a DIY stock picker.

Reinvesting dividends while you’re saving improves the picture, too.

But I still believe that a 100% equity portfolio is a young man or woman’s game, given how long a crash could endure. As we age, we should take less risk when investing, not because our heart can’t take it but because our time horizon can’t.

(Our questioner acknowledges this. Again, the answer is in the question!)

Finally, I never want to be a forced seller of shares

In the US, where dividend yields are lower, it’s normal to plan to run down a share portfolio by selling some proportion each year to create an income.

Indeed, the various studies you’ll see on the 4% withdrawal rule are based on this. So it’s not true that even a pensioner needs an income from bonds – theoretically they could sell their shares for spending money instead.

However I’d hope to live off the income from my portfolio in retirement, rather than actively selling – again because capital values are far more volatile than dividends.

The last thing I’d want to be doing if I was 75-years old would be to flog my marked-down equities in a bear market just to pay the heating bill / Majestic Wine tab / chorus girls.

I fully expect that at 75 I’ll have a slug of bonds as part of a diversified income portfolio. This should give me a good shot at living off my investment income, without having to touch my capital unless I choose to.

The bottom line on investing in bonds

While holding some percentage of bonds relative to your age might be a good rule of thumb, there’s no law that says you have to.

Also, I think private investors (as opposed to institutions) can often substitute cash in high interest deposit accounts for at least some of our bond holdings. While cash and bonds are not the same, cash will do a similar job in cushioning your portfolio. (Given where bonds are currently, this is the approach I’m taking).

I think a 100% equity portfolio can make sense for some, especially when you’re young or your portfolio is relatively small compared to your other assets or your potential lifetime savings.

But bonds are an important asset class, and they’re not to be lightly dismissed in pursuit of an extra percent or two of annual return.

The times when a decent allocation of bonds (or cash) will prove its worth are the dark times when you could be very glad you kept them in the mix.

Comments on this entry are closed.

For some years now, I have invested 90% of my money in the Harry Browne Permanent Portfolio (25% in each of cash, gold, equities & long gilts). IMO it is as near perfection as is possible. It is low volatility, low maintenance (just rebalancing, when necessary), and virtually stress free.

In the last 40 years it has averaged approx 9% compound growth & lost a small amount in only 2 of those years. The point that many people miss, is that you mustn’t take any notice of the volatility of the equities, bonds and gold. You just concentrate on the ‘combined’ effect of the 4 assets. If you watch the portfolio for a while without investing any money, as I did, you will realise just how widely diversified it is.

Just one drawback – it’s very boring. That’s why I keep 10% in another portfolio for a little excitement. I derive much more enjoyment from it knowing that the bulk of my money, which I can’t afford to lose, is safe.

For more information – http://crawlingroad.com/blog/

A 100% equity based portfolio, with a simple 200 day moving average overlay system would outperform both types of portfolio listed in this article.

Both by reducing max drawdown and volatilty.

One thing I learned from William Bernstein’s “The Intelligent Asset Allocator” is that you can both lower risk AND increase returns from a certain level of diversification – is that the same thing as the ‘efficient frontier’ in your graph?

@Red Jester — Can you give us a link to long term evidence, please? 🙂 And evidence it will work in the future? And that it will do so after costs?

I’m not averse to looking at a chart and adding/reducing risk in my active portfolio, but I’m skeptical that there’s any simple and practical technical system that will work for the average investor at the portfolio level.

> As you age, you’ve less time to recover from crashes

There is the implicit assumption behind this that you cease contributing money and/or purchase an annuity. Monevator readers may be different if they’ve paid attention over the years 😉

If you have savings that are more than required to pay your needed income, or you are using drawdown with a SIPP I believe, your time horizon doesn’t stop on retirement.

I have zero (well, very low) income. I will be a net investor for the next 10 years at least, and probably twice as long. My Dad gradually built the value of his portfolio throughout his retirement – he was an ordinary guy working in a blue-collar job.

@ermine — If you purchase an annuity you don’t need to worry about stock market crashes at all. (You have other things to worry about…)

Fair enough, if your portfolio is very large and/or your income requirements are very small, then by definition you can take more risk, because you have a large margin of safety instead of the safety of extra time. The 4% withdrawal rule may have been found wanting in some scenarios, but equally there’s plenty of times when in hindsight it would have proved too conservative.

However delaying drawdown doesn’t mean your share portfolio can’t plunge in value or the dividend income be cut. It’s more that you don’t need to fear so much that this could happen.

Most people limp over the finishing line with less than adequate assets, and can’t afford to take such risks.

The aim of investing for most people is not to try to ‘win’ with the most money. Most should forgo that possibility for the real aim — to meet their life goals, particularly the ability to meet their needs when they’re not earning.

If someone has ‘won’ by age 60, say, I don’t see the point of risking it by going for 100% equities or even 80% equities on the off-chance that the next two decades will be especially kind for shares, poor for bonds, and more blessed with thankful heirs.

Incidentally, why do you think you’ll need to draw more in ten years if you don’t need to now? Most people’s income requirements fall with age. Are you planning to go out in style? 🙂

‘Equations abound, such as “hold a percentage of bonds equal to 100 minus your age”.’

Surely that should be “hold a percentage of equities equal to 100 minus your age”.

or, “hold a percentage of bonds equal to your age”.

@peteS — Oops, yes. Sorry, dumb slip. I’ve fixed it now.

As I say, great readers. 🙂

As a sub-30 investor, I’m 100% invested in equities (with the exception of some of my pension holdings, which will hold a few bonds and cash equivalents).

For the moment, it would seem to be the only game in town.

When I have another 15 years or so under my belt, I might consider introducing a relatively stable investment trust or two to reduce volatility, but for now I’m enjoying the ride.

In the last year, my ISA has seen -5% to +10%. Taken in the spirit of ‘only invest money you could afford to lose’, it’s all good fun 🙂

The best guide to the likely returns from an asset is the price you are paying relative to the cash flows you get:

Bonds = yield

Property = rental yield

Equities = yield

Cash = interest

Commodities…hmm have no yield

Right now if you buy a 10 year gilt you will get about a 2.1% yield, the latest inflation figure is 3.1% and the BoE say that its going to be above target for the next year or so

If you park money in UK government bonds for 10 years you are not going to make any money in inflation adjusted terms unless there is an economic collapse more severe than 2009 that is allowed to cause deflation (to put this into context in 2009 roughly half of the UK’s banking system collapsed and had to be rescued by the government)

All you can hope for from gilts right now is not to lose as much as you might have done if you had invested in something with a higher yield – I’m not sure that is even a proven thing given gilt yields are so low

I do plan to live larger in the years to come – it’s one of the tradeoffs that you make as an early retiree to take a suckout in income before the time everyone else in the firm gets to retire. If you plan it properly like RIT or TA (or presumably your own good self) that suckout isn’t too bad, but I didn’t do it that far ahead, so I get to eat the suckout. If anybody’s worried about that tradeoff, JFDI… The magic of seeing the seasons for real rather glimpsed dimly than an office window are more than enough compensation.

In my case I have cash I saved in AVCs, which I will only get when I draw my FS pension which sort of takes the place of bonds, so I am a 100% equities guy. I saw my Dad run this policy, effectively balancing a equity portfolio against the diminishing real value of his FS pension, and it worked well for him – his portfolio grew even while he was retired.

The usual stock:bond scenario sounds great for people who are looking to do the typical work to 60/65 whatever and then retire 100%. It definitely doesn’t work for extreme early retirement – look at ERE and MMM. I am an averagely early retiree, and it doesn’t really work for me but maybe the FS pension changes the parameters somewhat.

I’ll need to draw more in ten years, not just because I aim to live larger and hopefully DW will be in a position to join me with that by then, but also because the government will steal from my savings, and from my FS pension by devaluing the value of the currency. Britain is still in a very deep hole and owes a shedload of money. You already referred to the preferred solution to that debt in the article. Old gits need equities too, IMO 😉 My equity portfolio will be about half the capital underlying my FS pension at the point of drawing it. It’s some degree of insurance against that inflation.

I saw what happened to my Dad – after 20 years of retirement income from his equity portfolio was a greater proportion of his income relative to his pension.

I’m with your reader. Bonds are overrated, particularly in the high proportions people advocate for old gits. You need some fixed income, but remember that in theory you will get your state pension at some point which is fixed income too, about 5k p.a., equivalent to about £100-120k investment capital, and very, very, bond-like. Paying down your mortgage gives you a tax-free income of the same amount or more (it would cost me £7k p.a. to rent my own house, and 2k a year easily deals with servicing). So that’s about 200k of bond-like investment. It’s easy to end up with a lot of bond-like elements to your income profile/net-worth without explicitly owning bonds IMO

Economic crisis and market crashes are usually the time when you’re more likely to lose your job (and be force to sell your equities just to survive). Another reason to diversify.

Even if you feel safe because you are government-employed (like me), you may have to face severe wage cuts.

Great article, and good to see comments from the estimable Ermine. Like him I escaped from The Firm with a decent FS pension. I also had a tidy sum in a freestanding AVC scheme and some ISAs. So what do do with it?

I did my homework, read everything on Monevator (note: other investment blogs are available) and decided to sign up for Bogledom a.k.a. stick it all in Vanguard trackers. I really can’t be bottomed to pick my own portfolio, so I was delighted to read about the LifeStrategy funds. Catatonic investing, that’s me!

My only difficulty was which fund to go for. I’m 60, so the formula says I should pick the LifeStrategy 40% equity fund. But as The Investor asks above, should I really invest that much in bonds?

I like to think Vanguard have designed the right product for the job. There’s a reasonable diversity of funds in the 60% bond allocation and automatic rebalancing between them.

So I stopped worrying and went for LS40. Now I can slump back into my post-retirement catatonia…

Lots of analysis, numbers and graphs here but the real answer is very old and very simple – don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

Where to begin…….

Milton Friedman said “there is no such thing as a free lunch”. There isn’t. Sacrificing returns for illusionary safety is no free lunch, it’s a very expensive one.

That graph that offers the free lunch is the risk/reward graph for one single year. The same graphs of 10,15, 20 or 30 years show a completely different picture. After about 10-15 years bonds are riskier than equities (see Fig 2-5 in Stocks for the Long Run). If your horizon is longer than 15 years you are sacrificing a massive amount of return for no extra safety.

If I were a 60 year old investor in 1999 I would have been riding the up elevator for the previous 20 years. That is 20 years with a (real) return over 12% per year so losing 20% shouldn’t hurt too much. This is not a one-off either. All big crashes, including Japan, come after crazy runs to the upside, they don’t just happen out of the blue. The only ones who truly get hurt are those who climb aboard at the last minute (or worse still, buy on margin). The rest just lose a portion of their ill-gotten gains.

Where I do agree is you should keep a cushion to ensure that you are not a forced seller of stocks and for that I prefer cash……being a forced seller of bonds can be very expensive too, and when they turn down it can be for far longer periods than equities. US bonds (real) were horribly negative from 1946-1981. That’s over 3 decades, something that stocks have never got remotely close to.

@Ermine

Is there really anything more to your strategy than “it worked for my dad therefore it will work for me” and then working backwards to justify the answer?

Just saying…

I think this is called heuristic bias, but I’m not sure I can spell it

@Neverland the learning I took is that one should beware when everyone says a FS pension is the safest. It is in certain ways, but not in others. The learning I took from my Dad’s experience was that over a decent retirement period inflation seriously damaged his FS pension, which was perfectly adequate at the time of retirement. His share portfolio stayed the course – in 2009 the income was achieving parity I believe, though unfortunately I can’t ask him now.

My deferred FS pension is better than his because some things improved FS pensions in the meantime, and because I earned more than he did in real terms. The learning, however, is that a share portfolio hedges certain kinds of risk. There are similarities in the two positions, and the solution (a form of diversification) is the same.

If I had a SIPP and had to turn it into an annuity, that is pretty much the same as a FS pension once purchased, barring that you need to save more to get the same result these days.

It’s got the same problem. The hazard of years of excess inflation is much higher, however IMO now than when my Dad retired. If my FS pension holds its value and my share portfolio goes sideways that’s fine by me.

I’ve seen that drop in value of a annuity-like investment. You don’t feel inflation kill you because it does it stealthily, one slice at a time, and the numbers still keep going up. For that reason if I were starting now I would make sure I had an equity portfolio in ISAs that I would hang on to as well as a SIPP that I’d have to annuitise. Len’s HB portfolio is another way of doing the same, probably wider in scope, and if I had enough time I’d probably use that.

The rule that you should hold 100-your age in bonds only makes sense if you are going to purchase an annuity with that lump sum. as it means you gradually exit the stock market as you come up to getting a lump to purchase your annuity. You’re exchanging stock market risk for annuity rate risk, as many people have found out over the last few years.

@Luke — Thanks to you (and everyone else) for your thoughts.

Your last line sums up why 100% equities is a young man’s game (“Money you can afford to lose”). At some point, when you’re not earning and you’re living off what you stashed away, what you can afford to lose changes. Good luck, and great start.

@Grinning Chris — A lot to be said for simplicity and kicking back. 🙂

@BeatTheSeasons — Yes, theory has the same root.

@Jane — You’d think it was clear, wouldn’t you? 😉

@Neverland — There are times when not losing your money is a great result. I’m not betting this is one of those times, personally, but you never know. Even 10% or so in bonds or failing that cash will give you some skin in that game.

@Juan — Well said. Another issue is that financial crisis are by their nature unpredictable. Sure, it looks like a nailed on certainty that 10-year gilts will return nothing in real terms in the next 10 years. But deflation would change that. (Do I expect that? Absolutely not. Is it possible? Absolutely.)

@ermine — Thanks for your detailed response. Nobody is saying don’t have equities, even the standard age-based rule of thumb would have you 50% or so in equities, and 40% when you’re 60. I’d just add that going by your age, your dad presumably was invested through the biggest bull market in equities and bonds of all time… Something to keep in mind. 🙂

@Paul S — Well, I don’t know what more I can say. I’ve written over 2,000 words here to do my best to explain the fuller picture about bonds and what they’re for, and how for most people investing isn’t just about maximizing their overall return, and how nothing is guaranteed. I guess I’ve failed.

You’ve read Jeremy Siegel’s book about US returns and seem to be saying it’s your way or the highway. (At least I am assuming that by your tone here and in your comment on the other thread, perhaps I’ve read it wrong).

I’m not saying 100% equities isn’t right for you. It sounds like it is.

For my part, I’ve been 100% invested in equities at points well into my 30s, to the extent that I was selling my possessions in 2009 to buy tiny slivers more of shares. I wouldn’t say no in my 40s, either.

That’s the irony, we’re pretty much in agreement for *our* purposes. I also happen to agree with Neverland that government bonds look poor value here, as I say in the article itself. (It’d be much easier if we were having this discussions when bonds didn’t look absurdly overvalued!)

But I don’t throw out financial theory lightly, or dismiss other people’s needs or desires — such as to dampen down volatility — as irrational. I don’t think they are.

All the best.

>Now, get pinching your salt. Somebody called 🙂

I don’t find too much to disagree with, but I think ermine makes a good point about the tendency of bondlike income to creep up on you. Unlike him, I already draw a FS pension, so I don’t have to screw down my expenses so much, but I do expect it to erode over time. The State Pension should give a useful uplift to this when it arrives a decade from now — more bondlike income.

By the traditional formula I’m am actually a bit light in equities at the moment (perhaps a bull market will fix that!) since I am fairly risk- averse, but my main reserve is cash, which for me is bondlike and although the return is virtually zero in real terms, it’s probably a bit more (perhaps a lot more) than I would get on Gilts, were I to switch allocation now.

Also, I have the luxury of a partner who is still earning, although it is unclear for how long that can be relied upon (we think visibility is one year, at least). Consequently, we are still in net savings mode and a proportion of that still goes into equities.

In the longer term I can see myself buying Gilts, but cash is likely to be my preference for the next couple of years at least. However, I see no reason to dispense with equities, even in old age, even though allocation might be down to 25% by then.

TI, Nothing personnel. I just think the evidence is so strong that , long-term, bonds are not safer and that all the scare stuff about stock crashes is scaring people out of the best investment going.

We will just have to differ.

By the way, I am closing on 70 and expect that the next 15 years, if I last that long (even if I don’t!), will return 9% pa real plus or minus 6% (90% probability). Check it out in 2027.

Sorry, that should have been 9% plus or minus 3%.

High quality post as usual. Just one note,

Cash in general is less risky than bonds. Still, recently Switzerland forced negative rates to maintain the peg. While the sterling is not pegged, it could still theoretically happen for other reasons. To make myself clear, I think this won’t happen but just wanted to present a case where you can get less than what you invested when you are parked in cash.

I’m fully invested in stocks myself but I don’t quite believe the stocks for the long run motto. Stocks for the very long run may have been true for some countries so far but again, in the very long run we’re all gone.

@Salis — Agree the bond-like income is an interesting observation (I’ve seen it with my parents, too). And yes, I think we’re all agreed cash is the way forward for us humble private investors right now. (Good luck hanging on to the back-up income!)

@K — Negative rates are technically possible (it’s sometimes mooted as another way to get banks lending) but I agree with you it’s very unlikely. I think it’s even more unlikely that you wouldn’t be able to get a High Street deposit account that lent at greater than 0% interest even if they did. As for stocks, I love them. I’m the biggest equity bull you’ll ever meet bar Jeremy Siegel and Paul S. But it’s with my eyes wide open to the downside, and the benefits of adding other asset classes to the mix in many circumstances.

@Paul S — I’ll level with you, I really struggle to see how this blog is scaring people out of equities (did you see my post just last Saturday for instance, which reminded people how I’d been pointing out the attractions of shares through the past four years of bad headlines?) But fair enough, let’s agree to disagree.

Looking forward to the update from 2027! 😉 I fully expect UK shares to be much higher by then, too. But I don’t *know* they will be…

> I fully expect UK shares to be much higher by then, too.

So do I. But in real terms? I am so old I recall looking at a newfangled pound coin and thing it wouled be ridiculous to buy a pint of beer with one. And I aim to get old enough that that will still matter to me, even if that pint is £100 😉

Great article and comments – this is a key issue for most investors.

Funnily enough, I have been thinking about this as well in the past few days

http://www.the-diy-income-investor.com/2013/02/portfolio-asset-allocation-search.html

(This includes some additional evidence that might be of interest).

A couple of brief comments

1) Choice of portfolio mix seems to be the biggest cause of differences in portfolio performance

2) As you point out, when Americans say ‘bond’ they usually means what we would call gilts

3) I prefer the other type of ‘bond’: corporate bonds (and other high-yield fixed-income)

4) My preference is for high yield: cash/dividends/fixed-income, approximately in equal quantities (and tax-free)

5) Investing is a very emotional exercise – reducing volatility (and having a more ‘boring’ portfolio helps to deal with the inevitable ups and downs of the market

6) I don’t think academic research has really looked at back-testing high-yield portfolios with this kind of mix

7) As gold does not produce income, I don’t hold it – but I like the general approach of the Permanent Portfolio

I think this is a good post, although it seems to have convinced no-one.

I do think for the average investor cash is a better asset than bonds(it is offers a risk free, fixed rate of return and so has zero correlation with other assets). Probably the only hassle is moving your money around to keep chasing the teaser rates. I do wonder if at some point governments will find a way to ensure banks pay for the protection they receive from the taxpayers and this might change the situation. But at the moment it does seem that savings(or were) are largely guaranteed via the regular taxpayers. Something for savers who moan about low interest rates to consider.

Judging by the comments shares are popular, but then this is an investment blog rather than a savings type one. I suspect your readers are financially less risk averse that most people(or believe themselves to be). There are plenty of people who steer clear of any investment at all. There are quite often people on MoneySavingExpert forums asking about no risk investments, or somewhere where they can store there endowment money for six months until there mortgage payment is dues…

@Dave — Good points. Just a quick note to add that the FSA’s FSCS protection we enjoy on our savings (i.e. on the first £85,000 of cash saved with a particular family of banks/institutions) is actually funded by a level on financial firms. So they pay for it, not taxpayers.

Of course, I agree that as we’ve seen taxpayers do provide the ultimate backstop, but I think it’s fair to point the above out (I see small cap financial firms who have nothing to do with banks complaining about it quite frequently! 🙂 )

@dave I agree with you about cash being in some respects a better asset than bonds (particularly in the current unusual monetary conditions). The rates on the best cash accounts are often not as ‘bad as all that’.

A couple of quick general observations.

First bonds have the advantage of actually rising in value when equities do badly whereas cash just stays the same.

In usual conditions over the medium term returns on bonds will beat cash.

I share The Investors view that currently bonds are priced as someone said for return-free risk rather than the normal risk-free return

The wisest bit in the post for me was the observation that you don’t really understand your own risk tolerance until Mr Market has well and truly run you over. I thought I was fairly risk tolerant but it still really upset me to see my savings disappear (and I am still working) in 2008. If I had been nearer retirement I am almost sure that I would have lost my nerve and sold out near the bottom.

The rule of thumb never to have more than double what you would be comfortable to lose in a year invested in equities is now part of my portfolio asset allocation planning.

Don’t forget how bond-like your job is!

– Bond-like job (e.g. civil servant) – give your portfolio in nudge more towards higher volatility.

– Equity-like job (e.g. Salesman on commission) – lower your volatility (& have a bigger emergency fund.)

(I use “volatility” as I think “risk” is a misnomer, for the reasons everyone has mentioned.)

Note that I think there are other ways to lower your “risk” than just having a bond allocation! There are a number of “low volatility” ETFs (e.g. MVUS, LEMV) and plenty of investment trusts which have significantly lower volatilities than average.

Personally I have a tiny direct allocation in a ‘war chest’ that I plan to use for spending in the near-medium term, either on me (stuff) or future me (shares). As the amount is small and it is s short-term holding, I’ve gone for OEICs, all of which happen to be active. It’s like a mini portfolio:

* M&G Strategic Corporate bond

* SL GARS (hedge, but no rip-off fees)

* Fidelity Moneybuilder balanced (solid stocks + bonds – I don’t mind if I end up having this for years as it should just keep plodding away.)

I do have some other OEICs which I would dip into before my ITs, but I don’t consider them a war chest.

I forgot to mention that a fund I had also considered for my war-chest (but didn’t get as I don’t have enough money to make it worth the effort) was emerging market debt. I think it is a decent compromise!

It does seem to have had a massive run recently so perhaps now isn’t the best time, but it does seem a little odd to me that the government bonds from the indebted countries with bad demographics are much more expensive than the bonds from EM countries, both government & corporate.

Yes, of course, there is genuine risk of default with unstable governments, but if you are spread around enough, it should be ok. they do tend to be much more volatile than developed world debt, but still much less so than equities. (Note that they don’t anti-correlate in the same way as developed world debt, so there is still space for that!)

I know First State & Aberdeen have good EM bond funds, though they are fairly new. I’m not well versed in passives in this space.

The one I considered though was Investec EM Local currency debt. It seems to me that we will have higher inflation at some point in the future, so having stuff in all sorts of random currencies seems an easy hedge. (Yes, I know they countries involved have much higher inflation anyway, but that’s priced in.) Again, I’m not sure of passive vehicles here.

This seems a much better hedge than gold, which while everyone shouts “inflation hedge” about it, doesn’t actually seem to be backed up be the stats.

OC

@Greg I share your views about gold – as you say no source of return and not even a very good hedge against inflation. Surely too, gold is in a massive bubble at present?

I am sceptical about the merits of minimum volatility ETFs and I certainly wouldn’t see them as performing the same role as bonds / cash in a portfolio. I have to confess that I don’t fully understand how MV indexes work (a reason on its own not to invest). But even if MV ETFs reduce volatility when back-tested in ‘normal’ up and down markets, I am absolutely sure that when the market tanks 1987 / 2000 / 2008 then MV ETFs will tank too. I don’t care about regular month-month volatility but I do care about seeing half my accumulated wealth evaporate every decade or two. Only bonds and cash can preserve wealth when the market gets ugly.

FT article on MV ETFs

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/78b865bc-8091-11df-be5a-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2KKKtVw9x

I am a bit unsure whether foreign currency bonds are a good idea for the long-term. They involve a huge ‘bet’ on secular exchange rates.

This paper from Vanguard is good and brief. They argue strongly for currency hedging – I wonder if the frictional costs of this make it worthwhile.

https://www.vanguard.co.uk/documents/inst/literature/global-fixed-income-considerations-uk-investors.pdf

@

Bonds are misunderstood by many UK investors and I can see misunderstandings in many of the responses to this article.

To start with, returns from bonds arise from interest and change in capital values – the same as shares. Returns on cash are interest only, so cash deposits are quite different from bonds.

Bonds do not have to be held until maturity. This is a common misunderstanding that many people have. If you buy a 10y gilt with a gross redemption yield of 2%, then 2% is your internal rate of return if you hold to maturity – 2% is your guaranteed return. But if you sell the gilt after 1 year on a gross redemption yield of 1.5%, then the total return for the year that the gilt was held will be quite a bit more than 2%. Many people who invest in bonds do not hold them to maturity, instead they hold until they become short dated, then sell and buy a longer dated bond. This tactic typically delivers higher returns than the gross redemption yields would indicate due to the normal shape of the yield curve. It can of course go wrong if yields rise sharply, but that’s investing for you.

The main point about investing partly in bonds is that price changes are usually negatively correlated with equity markets – bonds go up as shares go down. Cash merely holds it’s value as equity markets decline.

A mixed portfolio of 80% UK stocks/20% gilts would have returned about the same as 100% stocks over the last 20 years, but with volatility less than that of gilts (due to the negative correlation).

Gilts may seem expensive at the moment, but is anyone seriously claiming that equities look cheap?

A bit more precise:

An ANNUALLY REBALANCED portfolio of 80% UK stocks/20% gilts would have returned about the same as 100% stocks over the last 20 years, but with volatility less than that of gilts (due to the negative correlation).

@PI

(I won’t mention gold again in fear of attracting the lunatic fringe. Though to be fair, I like the concept of the permanent portfolio, I just think 3 of its 4 components look bad at the moment!)

I’m not claiming that low volatility ETFs are a replacement for bonds, I’m claiming that they could be considered to make up the lion’s part of any stock allocation, then the bond part could be much less. They _will_ get beaten during dips, but not spanked like a standard fund. (Look at how they did in the Summer 2011 sell off.)

Having said the above, it could all be rather artificial, seeing as defensive stocks are rather highly valued at the moment. Perhaps they are a great idea any time except right now… (Tricky thing, investing!)

One neat* idea would be to get low volatility trackers, then gear up back to the same amount of risk (which wouldn’t be a huge amount and could be done by not overpaying the mortgage etc.). If the apparent pricing anomaly endures, this should be profitable.

As for the FT article, it doesn’t really say much to me. I see the banker recommends a VXX “investment”. What an idiot.

Cheers for the Vanguard paper. (I do like their articles, they are uniformly excellent.) To me it seems to give a glowing endorsement of global bonds (though it doesn’t cover EM bonds). Note that even unhedged, there is a fair amount of near-minimum area with international bonds in it.

As for EM bonds, many, if not most of the funds do hedge back to sterling. (I’m pretty sure the FS one does.)

* dangerous.

@Nae Clune

All this stuff about bonds is all well and good….but what was the yield on the 10 year gilt at the start and the end of this “last 20 years” you quote?

I have a pretty sure suspicion that at the start of this 20 year period it was somewhere slightly below the 12% 10 year gilts yielded in 1990 and at the end it was pretty close to the 2% they yield now

Just because 10 year gilts were a buy in 1990 at a 12% yield doesn’t mean they are a buy today at a 2% yield

@greg – I can see the attraction of the permanent portfolio but I think quite a lot of its current popularity is based on recency bias with respect to the recent gold bull run. I (like you I suspect?) see gold as a hedge against desperate catastrophic situations rather than a solid investment.

You obviously are well informed about low volatility ETFs. I have to confess that I wasn’t aware of them before you mentioned them (which is why I like this blog). The FT article caught my attention but I can see that it wouldn’t have much to offer a more experienced / knowledgeable investor . Having read a low volatility ETFs now my thoughts are:

– they may be more attractive to professional money managers (who have to demonstrate low volatility year by year) rather than private investors who only have to answer to themselves ( and can therefore ride 2-3 year periods of lower returns / high volatility)

– I am not sure that they are worth the TERs of 0.45 ish (compared with 0.15-0.25 for a standard tracker)

– the low number of stocks (67) in the MV FTSE 100 tracker concerns me

– I feel uncomfortable that the apparent out-performance has no satisfactory explanation in market economic theory – is it spurious / temporary ? or will market efficiency catch up with it in the next few years ?

– I think it is a given that over periods of a few years they will under-perform the market which would make me uncomfortable.

– I would be interested to know more about their performance in 2011 relative to the market. My hunch though is that a bit like low correlated stocks, they minimum volatility ETFs might perform worst when you most need them. ie in a bad market fall correlations tend to go up and perhaps MV ETF’s might not do so well either.

– MV ETF’s for me fail on the keep it simple test. Given the uncertainty around them I don’t think the POSSIBILITY of superior performance is worth the complication. That’s a personal view though and other more knowledgable / sophisticated investors might disagree.

Glad you liked the Vanguard article which as you say was informative with lots of data.

Thought provoking article and lots of interesting comments.

Personally, I do not hold gilts – I prefer higher yielding equities combined with a variety of fixed-income pibs and preference shares.

Equity markets can be volatile but if you focus on yield (rather than prices), I find these swings are much more managable from an emotional aspect.

The CS yearbook report was suggesting we all need to prepare for lower returns from all investments and asset classes as they are basically correlated to cash returns – a rapid return to higher real interest rates would mean a fall in the value of most asset classes. Estimated real returns on equities are likely to be around 3% – 3.5% and gilts could well be flat or even negative.

From my perspective, for the 30 yr old or even the 60 yr old, a large slug of equities will provide far better returns over the next 10 – 20 yrs – ride the ups and downs of the market with a focus on dividends.

I’m not that hot on low volatility ETFs! I just have an interest in different types of passive funds. Cap-weighting makes sense as far as seeing how the market as a whole is doing, but I can’t see any particular reason why it is sensible to invest according to a cap-weighted index.

One of the advantages of cap-weighting is that you don’t need to rebalance, unless the constituents change, but with synthetic ETFs (of which I think the arguments against are just PR bluster from iShares) this isn’t a problem.

I think cap-weighting gives a bias to overpriced as well as large companies. (This is why it makes sense to get a smallcap fund as well as large cap ones, to try to balance things out.) People argue that other methods give small / value biases, but I would argue that it is simply cap-weighting giving a large & overpriced bias!

Indexing methods that interest me:

The RAFI funds (particularly the US one PSRF)

Equal weight indexes

Low volatility indexes

Dividend Aristocrats (though dividend investing isn’t my thing)

(There are even a few ones over the pond like a “spin-off” tracker, CSD, and a “made recent buybacks”, PKW, tracker which are intriguing…)

It appears to me that all of them give better returns than cap-weighting and in fact, are less vulnerable to concentration risk as cap weighting. (The obvious example is the Nasdaq-100 where the equal weight tracker hasn’t been moved around all over the place by Apple, which makes up 20% of the cap-weighted index.)

Understood or not, it does seem small-and-value has led to outperformance for a long time, through various market conditions.

As for the methodology of making up the index, I don’t know the details but selecting for low-beta stocks doesn’t seem that esoteric, and equal weighting certainly doesn’t. (Though naturally, equal weighting would give _higher_ beta not lower due to the small caps!)

Personally, I don’t currently have any of the ETFs mentioned, though I am keeping them on my radar! My approach is to get a load of uncorrelated ITs with a few trackers (currently all cap-weighted but perhaps not for long) where I don’t think IT’s add value. I do have a few OEICs for a war chest and a few more where I’m just dabbling so don’t want trading fees.

My ITs include:

AAS, BIOG, BRSC, FCS, SMT, HANA, TEM

MYI, CTY (Vanguard LS-100)

CGT, RICA, PNL

Each brings something different to the portfolio and while the top row go all over the place, they average out quite nicely! The middle couple are more mainstream with the bottom row providing a nice low volatility bed.

Excellent article.

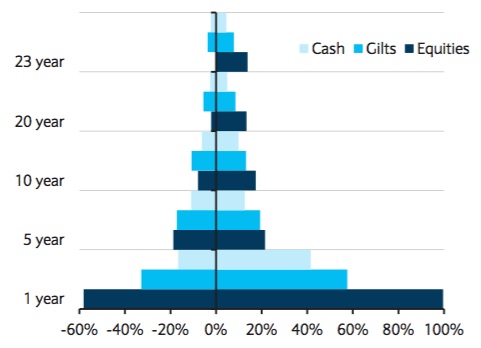

The ‘outperformance of equities may not continue’ argument is important. If you could guarantee that the performance of equities was in line with a probability distribution of the past returns on equities over the past 100+ years then for those young enough to have a very long time horizon then 100% equities would make sense. For example from figure 7 of chapter 5 of The Barclays Equity Gilt Study 2012 over 23 years you are guaranteed a real return from equities from a passive strategy (assuming you keep investing costs down). However the argument that blows that away is that ‘outperformance of equities may not continue’.

One of the best books I’ve read was Rethinking the Equity Risk Premium (was a free download when I downloaded but now 77p).

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Rethinking-Equity-Risk-Premium-ebook/dp/B006ZOVU4U/ref=sr_1_1?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1360399687&sr=1-1

There are a range of arguments on what we might expect the equity risk premium to be going forward and whether we would expect it to vary with time.

As others have said, I think savings should be considered instead of gilts. At the moment if you shop around for the best savings rates you are able to get a better rate than the average saver. That is not possible with gilts as effectively they are priced by the market at a consistent single interest rate for any given term. Ignoring other arguments on the cash vs gilts debate and the current position of the unusually low redemption yields priced into gilts (that have been covered in other discussions here) we could expect savings, for those who shop around, to produce better returns than gilts.

If we think that, we then have to ask what special protection can gilts give us long term that savings accounts can’t. Probably a long term deflationary scenario is the only one. There is a scope in that scenario for best savings rates to fall to close to 0% and current long term gilt yields are above that.

@Monevator, if a currency has a negative rate by the central bank, the retail/private banks kind of have to have a negative deposit rate as well if the negative rate persists for some period of time, else they’ll end up with losses. E.g. accounts in CHF were charged interest instead of payed interest when SNB set negative rates. Again, I think this is not gonna happen as the sterling is not pegged to anything.

@K — Yes, if it’s a long-term situation it would perhaps be unavoidable, and the currency issue is interesting (though perhaps avoidable for limited/ring-fenced retail accounts). But as I say, I don’t think it’s going to happen in the UK in almost any circumstances.

We see banks paying “too much” interest on savings accounts all the time, and I think they’d bite it for retail savers prepared to look for a better rate.

E.g. We can get 2% on a one-year cash ISA now, but banks can only be getting 0.3% on a one-year gilt and LIBOR is just above 0.5%.

Obviously then the banks are subsidising the 2% rate they pay us on those ISAs versus the base rate, whether through passing on the profits from riskier investments (e.g. mortgages and other loans to customers), and/or else treating the 2% per annum as a cost of marketing, hoping the customers will stick around earning profitable rate in the future.

I think that’d happen in a minus 0.5% world, too.

@greg – I agree that non-cap weighted indexes are interesting and offer potential advantages. I even hold a tiny (<<1%) percentage of my portfolio in Powershares FTSE 100 RAFI (PSRU) as an experiment. Personally though, I would be more upset if the non-cap weighted ETF under-performed than I would be please if it over-performed (if that makes sense). Because of this I don't plan to move away from the standard cap-weighted indexes.

I don't use investment trusts because the whole NAV discount / premium thing annoys me. I can see their merits though.

Great article in the sense of raising good comments.

My simple point is that the shares/ bonds allocation issue is, in practice, quite complex and rules of thumb formulae become almost meaningless in many cases. For example, the age, financial resources and strategy of the investor can vary widely.

In my case, I am a 68 year old 100% equities lifetime dividend investor with a modest lump sum set aside for emegencies which I can top up from time to time as necessary. I can easily live with a 50% reduction in dividends. I have no fear of the major share price falls that happen from time to time as I have no intention of selling. What am I missing?

@DownAgain — In the circumstances you’ve described, you sound very well placed. Congratulations! 🙂

Your points about individual circumstances are fair enough, but I do think people raising this line of ‘attack’ (I don’t mean in the sense of confrontation 🙂 ) are making a bit of a spurious criticism about the *rule of thumb* regarding bonds though.

Most people are not in a situation in retirement where they have large amounts of excess income from their investments, the potential for extra income from elsewhere, a working partner, the ability to radically downsize, or some of the other things we’ve heard raised as counters as in this thread. There all valid for them, and I applaud people investing to suit their own circumstances, but they don’t negate the general principles of risk reduction as you age *for most*.

It’s a bit like someone saying: “The laws about compulsory seatbelts are over the top! I drive around deserted country lanes in the Orkneys Islands in a tractor at a maximum of 10mph, and I’ve never had a problem”.

No, but that’s not why the ‘rule’ is there.

In your case, I’d say there are two other risks to beware of, none of which I’d be too concerned with in your position but there you go:

1) Legislative risk — There’s always a chance, however remote, of the law / tax picture changing against the generous dividend taxation regime we now enjoy. In the distant past (e.g. the 1970s) dividend tax rates were far higher. I am *not* saying that is on the cards at all (or that it would be wise policy) but we live in changing times. At least if you mix your income sources you diversify such legislative risk. Of course, you may decide to cross that bridge if it ever happens, but that itself introduces other risks.

2) Inheritance / bequeathment — This hasn’t been mentioned before in the thread, and may not be relevant, but if you intend to pass on your assets then to some extent market risk is still a factor for you. Again I’d not be bothered, personally, but for some it’s a factor worth considering and looking into.

Bottom line: Once you stop earning and are reliant on your nest egg for life, you need to protect/grow that egg as best you can. Some will decide to stay all-in equities for the potential benefits. Others will see the risks as greatly outweighing the rewards. In my view it will depend on personal circumstances.

I get the impression that much of the discussion here implicitly involves fixed interest bonds, rather than Index-Linked Gilts or TIPS. Why?

@dearieme — In terms of the original article, I was thinking about both kinds of bonds, but writing more with conventional bonds in mind it’s true.

Index-linked government bonds are I think almost a different asset class (not wholly of course, but in practical terms — in normal times) and really require their own article.

I haven’t got around to such an article yet because real yields have been puny to negative for the past couple years, and I see no rush to follow pension funds and other institutions forced to buy such securities, though of course the same could be said of conventional bonds at current prices.

The article itself is meant to be about the long-term, not this strange current environment.

Thanks for stopping by!

Are you not a victim of your own self by trying to time when you dip in and out of bonds? Why not just invest in short term bonds now and then switch to long term bonds when you see the tide of the wave turning??

Also, as a passive investor shouldn’t you have a allocation that you stick to without too much disruption, when you first put your allocations together surely there was a percentage for bonds, what happened along the way? You wouldn’t pull your allocation in equities if the price was too high/low in favour for a different asset until you felt things were as you’d like them to be? It seems you are actively trying to beat the market with passive products i.e. investing in cash with the view to switch to bonds when bond yields increase (prices decrease).

I’m playing devils advocate in the spirit of self-development

Does anyone know of any funds – ETF or active – that invest in global inflation linked bonds? I’m tring to follow Tim Hale’s excellent book Smarter Investing and I agree with him that inflation linked global bonds should be there, if only just to prop things up when markets crash. However, other than the Fidelity global inflation linked bond fund (actively managed), I am struggling to find either a better active alternative or ETF that’s in global bonds and hedged back to GBP. Any ideas??

Some may argue that bond funds produce returns of, say, 2% or 3% a year above cash, but there is an initial charge and then an annual management charge of 1% to 1.5% a year on that fund. Therefore a huge proportion of the return that you expect is being eaten up by charges.