What caught my eye this week.

You can passionately make the case for financial independence being hugely positive versus retiring early being a bit of wild goose chase – and I have. But if some unfortunate office drone has just been sent to the seldom-visited filing cabinets in the strange rooms behind security to spend a week hunting for all the paper-based invoices from O’Brien and Sons from the 1970s, well, good luck getting them to vote for the job.

Of course many jobs are rubbish. But from the earliest days of this blog I’ve argued they used to be even worse. All repetitive manual paperwork and calling Mr Blimp ‘Sir’ as he dressed you down for wearing the wrong kind of tie again.

Not to mention the love of coal mining and sweating in an iron foundry that middle-aged middle-class columnists love to champion – but would be dead doing themselves in a fortnight.

Somebody’s got to do it

There’s a big difference between a job being unsatisfying and the actual work being pointless or futile.

Yet a decent chunk of the Retire Early and Forever cohort of the FIRE scene 1 believe that modern jobs are literally pointless – even to the organisation they’re working for.

They cite arcane tasks steeped in ritual but bereft of meaning, such as preparing a presentation for a senior manager that they suspect will never be read. And to be fair most of us can agree with them about all those pointless meetings.

Overall though, I believe most of these jobs have a function – at least in the private sector.

Sure there might be a bit of padded headcount here or some not-yet-optimised away employees there.

But even badly-run companies won’t survive for long carrying too much deadweight that’s doing nothing to keep the operation going.

Strike through

I saw this when I was managing my own small start-up. There were never enough hands for all the work to be done – much of it indeed annoying or trivial-seeming.

Some of those hired hands were a bit useless, I reluctantly concede. But not what we had them doing.

At least not from the myopic perspective of our company. Which is to say: nobody was curing cancer.

That is clearly a big issue for a lot of people. If pushed, they can see their work has a function. But they don’t see the point for humanity, I suppose.

The other issue is the typical cog doesn’t have a good view of the machine. Your useless role writing up user manuals that you believe nobody reads might be a lifesaver one day when your company’s minor malfunctioning gadget brings a giant operation to a halt. Not to mention it’s hard to sell stuff without operating instructions, even if most people ignore them. So they’re a function of sales and marketing.

Or just ask whoever presumably has done something wrong at Crowdstrike. I don’t know what exactly crippled half the world IT system’s following its software update yesterday. But I’ll bet it’s a trivial-seeming thing gone wrong.

Not some exciting security function that was dreamed up by the company’s brain trust and lovingly laboured-on like Michelangelo working over a ceiling. Rather, the version control or installation code or similar.

Boring stuff that gets no acclaim, and that nobody rushes out of university to get started on.

But which is quietly absolutely essential.

It’s a wonderful life

For more on all this, you can click over to Byrne Hobart’s devotional paean to the complexity of modern workplaces on Capital Gains this week.

In taking down a Bible of the Modern Work is Rubbish movement – the late David Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs – Hobart writes:

Graeber estimates that roughly half of all work fits his fake job categorization, which implies that the economy’s productive capacity is roughly twice the output we actually get. It would be a pretty big deal if this were true: we could have a lot more leisure, and a lot more stuff.

And there are people motivated to make this happen! The strongest single argument against Graeber’s book is: did anyone at Bain or McKinsey read it? What about KKR and Blackstone?

Did any owner of any business of any size read it and say: “What a sec! That’s right! Most jobs really are fake jobs designed to make rich people feel good about themselves. But what makes me feel good about myself is having more money, so I’m going to start firing people and keeping the money.”

The closest you can get is Elon Musk at Twitter, which did reveal that the service could keep running, and ship new features, with a lower headcount. But that happened at a company that was notoriously inefficient, for years, and one where it’s widely-agreed that they unnecessarily blew their lead in short-form many-to-many communications, and took too long to get into messaging.

If there’s one large-scale example of the thesis playing out, and the thesis holds that it’s describing a ubiquitous phenomenon, something doesn’t add up.

Hobart rightly concedes that many jobs aren’t fun to do and also that many people are in the wrong jobs for them, personally.

But as he concludes:

The world is full of mysterious economic phenomena. You should expect it to be!

A world where you can consider a random career or business for a few seconds and instantly identify a way to double its efficiency is a much weirder world than one where those mysteries tend to have satisfying answers.

It’s also a world whose sizable and growing aggregate wealth is a big mystery: if we’re wasting more and more of our time, shouldn’t we be getting poorer?

Go give it a read and see what you think.

Honestly, with all the dire warnings about the typical worker’s imminent replaceability by an AI drone, it’d be nice to think we were just giving each other things to do out of habit, ego, stupidity, or an obliviousness to the bottom line.

In an AI-powered world we could then continue to pay ourselves to – metaphorically – dig holes on a Monday only fill them up again by Friday.

But real-world capitalism is far too ruthless for that.

Have a great weekend.

- Financial Independence Retire Early.[↩]

The main reason people try to keep up with the Joneses are the status games we all play.

Humans are social creatures. And throughout our evolutionary history, it made sense to be intensely concerned about our ranking within the tribe.

Status could mean the difference between eating, having children, and meeting – or meting out – violence.

Not to mention whether you get a backstage VIP pass for Glastonbury or you’re pitching your tent by the loos.

Status games are everywhere. Even when people have few expensive material possessions, you’ll notice they’ll find a way to get a status boost.

Think of holier-than-though students who flirt with communism. Impoverished kids trying to get an edge with a pair of rare Nikes. Or frugal savers who position themselves as above “all that consumerist crap” and in doing so aim to turn their practical choices into moral virtue.

As you do

Another – better – reason to twitch the curtains to see what our peers are up to is imitative learning.

We learn to fit in and get on by copying each other. It’s a social reality.

Before you say you’re “above all that crap” too, spend an hour in a kindergarten. See how impressed you are with the kid who ignores all the norms of how to eat, when to shout, and whether to use the floor as a potty.

Of course I still like to believe I’m different. Maybe you do too.

But the base rate before we even think about diverging is to know what others are doing with their lives.

Which is usually school, job, taxes, marriage, mortgage, kids, taxes, pension, retirement, taxes, death (and maybe taxes).

All fluffed up

Some of these aspects of living are easier to pick up by copying – perhaps subconsciously – than others.

Fitness habits, say, or how to handle your child’s temper tantrum. Or when to suck up to a boss, which may be much the same thing.

But other stuff happens behind closed doors. We can only wonder how everyone else is doing it.

Perhaps that’s a secondary reason for the popularity of porn?

We’re all curious as to how everyone else is getting it on. For purely intellectual reasons, you understand.

Of course, for most people pornography is unrealistic. (The Accumulator excluded. He’s a legend in the bedroom and I claim my £50 in PR fees.)

We still can’t help benchmarking ourselves to all that athletic activity.

And similarly, we keep one eye on the Joneses – despite knowing better.

We usually don’t know what the Joneses earn or how they invest their money. As with their habits between the sheets, we only get the vaguest sense of whether we’re doing it right from the output presented by others. We mostly don’t know the inputs that enable it all.

And again, before you say you’re above such petty comparisons please spend 30 minutes sitting on the pavement outside Tesco asking if anybody can spare any change.

Then come back and tell me you’re oblivious to your status.

Size matters

We all agree judging the Joneses ‘success’ by the car they drive or the handbag they tout can be as misleading as listening to a 17-year old boasting about their body count.

Nobody is doing an audit here. The Joneses may be whacking it all on a credit card. Perhaps none of that spending is making them happy, anyway. The whole shebang could be a mask.

Alternatively, they might be having a ball. Zero debt and up to their eyeballs in well-provisioned pensions, an ample larder, tasteful consumer goods, and a steady supply of plane tickets to sunnier climes.

Who knows? To go deeper we’d need a more complete picture.

This might be one reason for the appeal of our FIRE-side chats on Monevator.

The subjects are Joneses of a sort, sure. But the interviews highlight factors we understand to be more consequential traits to study.

How they invest, say, rather than how they do up their homes.

Or how they save, versus where they shop.

These traits are usually invisible to us in everyday life. Yet they’re much more indicative when it comes to achieving long-term financial success than material proxies of status.

Behind the numbers

Broad brush surveys can also give us insights into what goes unseen with our fellow strivers.

Even the wooliest statistics can be surprising.

I was somewhat taken aback in 2023 to discover via a simple poll on Monevator that over 60% of our readers are higher or additional-rate taxpayers, for example.

From years of interacting with readers, I know your net worths typically skew higher than average, too.

This data has implications for the type of articles our readership is likely to want.

But it should also inform how we all approach reader comments left on our site.

Being relatively wealthy – or on their way to it – most Monevator readers’ lives won’t change much if they lose £5,000 in a downmarket, for instance, or if they make an extra £2,000 a year.

That is very different to the norm on many other sites – especially discussion forums such as Reddit, which skew a lot more young and up-and-coming.

Indeed, in an ideal world you’d see a reader’s age, income, net worth, dependents, and even their monthly outgoings alongside every comment they make – whether here or on Reddit.

That’s obviously impossible. Instead we can only get a sense of who someone is if they repeatedly write under the same username over a very long period of time.

The vast majority do not, which is why I urge constructive skepticism when it comes to financial opinions on the Internet.

You nearly always don’t know who you’re talking to. Yet personal context can change everything, turning prudence into folly or an investment into a gamble.

One (very rich) person’s £20,000 meme stock punt gone whoopsie, for instance, is another (much less rich) person’s would-be house deposit turned to smoke.

How people invest their pensions on one online platform

Enter Interactive Investor’s new SIPP index (note: affiliate link), which has been cited by a few mainstream financial writers recently.

I thought perhaps this would give us some interesting insights into how people are choosing to invest pensions, a decade into the post-freedom era.

The report – which II is touting as a quarterly ‘index’ – certainly alludes to such insights. Both on how people invest pensions in the accumulation phase, and also when they begin to drawdown an income.

So as a financially-curious human – let alone an investing blogger – it promised to be interesting reading.

In truth though I gleaned surprisingly little useful info from this first incarnation of the report.

That’s because the platform tells us what kinds of financial vehicles its customers choose to invest pensions into – but not what those funds, trusts, or other stuff actually hold, except in the case of cash.

So we discover:

Source: Interactive Investor

…but what does this really tell us? (It probably also doesn’t help that I struggle to tell the difference between some of these shades of blue!)

True, we can see there are more funds and direct equities in the accumulation phase, and a lot more in investment trusts in the drawdown phase.

But without knowing what assets these funds are actually invested in, this information is pretty useless.

What’s more, is a greater share of investment trusts held in drawdown accounts because people are choosing to lean on these products as a source of retirement income?

It could be. Or it could be that Interactive Investor clients who are already in drawdown are from an older generation, and so are simply more inclined to favour investment trusts in the first place.

A table showing the most popular funds held in SIPP accounts before and after drawdown doesn’t shed much light either:

Source: Interactive Investor

Good luck getting much insight from this data dump – except perhaps that it’d be nice to own shares in Vanguard.

It’s what we invest pensions into that matters

What would be more useful would be to see what assets such everyday investors are holding on a ‘look-through’ basis.

For example, if they own a LifeStrategy 60/40 fund, then 60% would be allocated to their equities bucket and 40% to their bond bucket.

Total everything up across all their funds, trusts, and other investments, and we’d see a more useful overall asset allocation picture. It’d also show how it shifts through time too as they move into drawdown.

Instead the II SIPP report presents an old-fashioned marketers’ perspective on investing.

The report tells us what products are popular, which is doubtless interesting if you work at Vanguard or FundSmith. But it doesn’t tell us much about investors’ attitude towards particular assets – or even risk.

It is like when friends ask me about investing and tell me they “have an ISA”.

First you have to ask whether it’s a cash ISA or a stocks and shares one. If the latter, you must ask them what’s in it. Finally you gently explain that the ISA is only a wrapper – it’s not the actual investment.

It’s similar with a fund or an investment trust. What matters most for investing insight purposes is what these vehicles hold, not how they’re set-up and marketed.

Trend spotting

To be fair, the report does offer a few interesting tidbits in the commentary, albeit based on data that’s not surfaced to us as readers as far as I can tell.

We learn:

- Passive funds have grown more popular in the last two years. They now comprise a majority of the top ten most popular funds for both accumulators and those in drawdown.

- Younger customers are more into ETFs than older folk who prefer traditional funds and trusts.

- Female clients saw higher returns than male customers over the past two years across all ages. This appears to be because they hold more collective funds and trusts, and fewer individual shares.

- Younger clients in accumulation mode have seen much higher returns over the past two years than older investors in drawdown. That’s as you’d expect, because the latter should be taking less risk.

There’s the outline of a useful report here and I hope Interactive Investor continues to develop it. They get a lot more of this stuff to chew through in the US than we do, and it’d be churlish not to welcome additional UK-centric data.

But I’d like the platform to think more holistically about asset allocation for future iterations.

Rich pickings: how the wealthy do it

All this made me curious for more. So I hunted around and found a couple of fairly recent reports that do give us more specific asset indications – albeit not for what’s held in SIPPs alone.

First up there’s the Resolution Foundation’s report on the wealth of richer families.

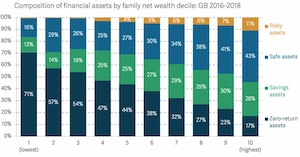

This report was published in 2020, so take it with a pinch of salt – we’re on the other side of a bond market rout, after all, and some of its data goes back to 2018 – but for what it’s worth the Resolution Foundation reckons wealthy families were financially positioned as follows:

Source: Resolution Foundation

This is somewhat interesting, if dated – ‘zero return’ assets being to 2020 what flares were to 1975 – but at least it shows us how a reliance on cash decreases with greater wealth, and also that risk-taking increases.

However as I read the report this chart only gives us a sniff of where people actually have their money. That’s because it only seems to apply to the ‘financial asset’ sliver of how the Resolution Foundation divvies up overall household wealth.

And crucially ‘financial assets’ would seem to exclude pensions:

Source: Resolution Foundation.

So we’re back to context again, right? If I have a chunky paid-up pension that constitutes a huge chunk of my assets, then I’m probably going to take more risks in my online share dealing account.

Anyway you can read the full report for further breakdowns, which partly unpick this while introducing other issues.

Incidentally, the Resolution Foundation’s subsequent two wealth reports don’t break down financial asset allocation at all.

Lies, damned lies, and pension statistics

The Resolution Foundation cites data drawn from the Office of National Statistics (ONS).

And poking around in the ONS archives does indeed flag up a treasure trove – albeit in rather raw form.

In particular, a 2023 data dump tells us how funded occupational pension schemes are invested, including asset allocation.

Loading the data into a spreadsheet yields the following ‘look-through’ breakdown of how pooled investments are allocated as of Autumn 2023:

| Asset class | Percentage |

| Equity | 35% |

| Fixed Interest | 10% |

| Property | 2% |

| Mixed asset | 35% |

| Hedge | 1% |

| Private equity | 0% |

| Money market | 4% |

| Other* | 13% |

Source: ONS. * We’re told ‘Other’ pooled investment vehicle asset types include cash, commodity/energy, structured products, unknown and with profits.

Job done? Not quite. The above data only breaks down pooled investments, but total pension assets also include direct investments into everything from cash to corporate bonds to unquoted private equity.

However these amount to only about another 11% or so of pension assets.

A bigger snag is the huge allocation to ‘mixed assets’ and ‘other’. This brings us back to the Vanguard LifeStrategy problem.

We could be looking here at 80% equities and 20% bonds – or 5% kumquats and 95% vintage cars! We just don’t know.

Still, the big picture seems to be much more than 50% in equities – I’d guess closer to 70% – along with a decent chunk in bonds and a smidgeon in cash.

Which seems about right?

Funds finding favour

Finally, another way to envisage how our financial assets are invested – again not only our pensions – is to see where UK investment funds have allocated their money.

For this I turned to The Investment Association’s latest survey – and I’m pleased to feature another colourful chart to conclude our romp:

Source: The Investment Association

Again, this information only takes us so far in understanding exactly what assets the Joneses have bought into.

For starters, while the Investment Association says…

‘our funds data includes assets in open ended funds, investment trusts, ETFs, hedge funds and money market funds’

… this notably – and not surprisingly – excludes cash and directly held property.

Also, many entities besides private individuals have money invested in funds. But it’s all captured here.

And even where the money is ultimately on the balance sheet of a private investor, it will include Richard Branson and the Duke of Westminster as well as you and me. Such riches will further distort things.

Also ‘mixed asset’ is in there again to ambiguously stink up our conclusions.

Perhaps the clearest takeaway from the graph concerns a different if now very familiar story – the shrinking amount of UK fund industry money allocated to UK equities over time.

We (mostly) don’t invest pensions in pie-in-the-sky

Googling around provides plenty of other snapshots that I could have included in my review above. I haven’t exhausted the Internet!

But I’m calling time on account of my sore fingers and your waning interest.

Perhaps there is a perfect review of how pensions are invested out there somewhere. Please do share any better sources you’ve found in the comments below.

So have we learned anything from this exercise?

Only really that most money is broadly allocated across a wide range of assets – and that allocations do change with age and (possibly) with the shift to retirement.

That isn’t a newsflash. But perhaps it’s reassuring that while AI behemoths, cryptocurrencies, and meme stocks clog the agenda, the moneyed Joneses continue to plod sensibly along with broad portfolios that will outlive any particular fad.

And our pensions should be invested that way too.

A question from a reader about ‘bed and breakfasting’ – and she’s not talking about English muffins versus the continental options:

Dear Monevator,

I have an old investing book/bible that tells me I should be bed & breakfasting my shares to reduce taxes. Is this possible in the era of Airbnb? (Just joking!) Seriously what is bed and breakfasting shares? Is it still even legal as I don’t think you’ve written about it?

Yours,

A. Reader

Dear reader! So-called bed and breakfasting was a now-defunct method to help you reduce capital gains tax on shares (CGT).

In the olden days – when mitigating taxes was mostly a sport for retired stockbrokers in the Home Counties – you would sell a fund or tranche of shares you owned one day to realise a capital gain – ideally for less than your annual CGT allowance – and then buy back the same fund or shares the next day.

Doing so reset your cost base. Which, in turn, defused the future capital gains tax liability you were building up when your fund or shares rose in value.

What a wheeze!

People typically did their bed and breakfasting at the end of the tax year. They’d sell on the last day of the tax year and then buy back the next day.

Bed and breakfasting enabled you to make use of your annual CGT allowance without losing exposure to an investment that you presumably wanted to keep. (Since you only sold it to defuse the CGT).

No more bed and breakfasting CGT

Bed and breakfasting was a simple operation. But it cunningly helped prevent moderately-sized gains from becoming liable for tax by defusing a portion of the gains each year.

Alas the whole scheme long ago went the way of paying urchins to sweep your chimney. Bed and breakfasting was crippled by tighter rules about when you can repurchase the same asset if the disposal is to count as a taxable sale.

In short: nowadays you can’t just sell and buy back the next day to defuse CGT.

Instead you must leave a 30-day period between buying and selling the same assets. Any less and you haven’t crystalised the CGT gain from HMRC’s perspective.

Thirty days! That’s not so much bed and breakfasting as bed and hibernating!

During those four and a bit weeks, of course, the value of your investment will fluctuate. So you could miss out on gains. (Or losses…)

What’s more, the CGT allowance has been cut and cut again in recent years. This means there’s much less headroom for defusing gains anyway.

On the other hand, we do enjoy a generous £20,000 annual ISA allowance.

And ISAs are entirely impervious to tax, which means that over the years you can build up a chunky tax shelter to hold your assets inside and never worry about CGT anyway.

Alternatives to bed and breakfasting to reduce CGT liabilities

If you do still hold assets in general investment accounts – i.e. outside of ISAs and pensions – then there are other options to bed and breakfasting, which exploit the same general idea of using up your CGT allowance to defuse gains.

They are not perfect swaps, but you could:

- Bed and ISA: You can sell a fund or shares you hold outside of an ISA and then put the money you raise into your ISA. Within the ISA you can repurchase exactly the same assets if you want to. From then on it can grow without concern for the taxman, like anything else in an ISA. The 30-day rule doesn’t count with respect to these ISA purchases. The obvious snag is your annual ISA allowance is limited in size. That restricts how much bed-and-ISA-ing you can do in a particular year.

- Bed and SIPP, bed and spreadbet, and so on: You can apply the same principle of Bed and ISA to other investment vehicles that give you the same exposure but do not violate the 30-day rule. But be careful not to let ‘the tax tail wag the dog’, as they say. (For example, money put into a SIPP can’t come out until you draw your pension. Meanwhile spreadbetting to avoid CGT has lots of risks for the unwary).

- Bed and spousing: Married couples and civil partners can keep an investment in the family when crystalising a gain by having one partner sell the asset, and the other party simultaneously buy it back under their own name in their own account.

- Give and take: Legally sanctified couples can also look into gifting each other assets. Such gifts are made at cost – rather than market value as would otherwise be the case. Swapping assets like this can be handy if one spouse is likely to have some capital gains tax allowance to spare or if they pay a lower tax rate. They may still face a taxable gain when selling the assets, but they could pay less tax when they do so than the other partner would. (I should confess that as a

lonely misanthropeirrepressible singleton, I’ve only ever read about these arcane ceremonies).

- Bed hopping: There’s nothing to stop you selling one asset to use up your allowance and then buying something similar but different with the proceeds. You could sell your shares in big oil firm Shell, say, and then buy shares in BP. Obviously you’re now invested in a different company, but you’ll still retain exposure to an oil major. Another example would be to sell an actively managed emerging markets fund and then buy an emerging market tracker. You can even swap global tracker funds from different management houses. (The latter is a slightly grey area. Perhaps choose funds that track different global indices for a belt-and-braces approach.)

- Bed down for a month: You could sell shares that you’ve made a good gain on, and then roll the proceeds into an index tracker. After 30 days you could sell some of the tracker to fund a repurchase of the original shares if they still looked good value.

Keep records of all these trades in case you need to report them to HMRC.

Worth doing, but better avoided

There’s a cost to churning your portfolio like this, and it’s not just heartburn.

Share dealing fees may be low – or even zero – these days. But stamp duty of 0.5% on most share purchases will make a dent into your capital. There are bid/offer spreads, too.

What’s more, if you plan on doing a return trip after 30 days then that’s going to double your costs again. (You could just sit in cash. But then you risk the market moving against you.)

Again, it’s always best to invest in an ISA or pension where possible. This keeps your investments shielded from CGT entirely. Start young and you can build up a substantial ISA portfolio, while annual pension contributions can currently be up to £60,000, if you earn enough. Though who knows how long before the politicians meddle with pensions again.

Some people do still have big portfolios outside of tax shelters. Maybe they’re rich, or they’re obsessed with investing. Or perhaps a lump sum like an inheritance overwhelmed their limited annual allowances.

If that’s you, then the methods I’ve talked about above are worth doing to prevent taxes eating up your returns in the future.