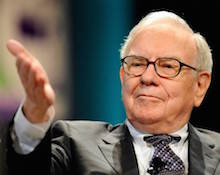

Over the past 50 years, Warren Buffett’s annual letters have attracted fans far beyond the shareholders of his company, Berkshire Hathaway.

Proto-Buffetts have long devoured the master’s words for insights into how he achieved an average return of around 20% a year for half a century – and perhaps to pick up a few stock tips, too.

But recently passive investors have also got in on the action.

Warren Buffett has repeatedly recommended index funds as the best solution for the average investor – whom he defines as nearly everybody, incidentally – but lately he’s become more strident.

Just last year Buffett revealed that when he passes away, the bulk of his wife’s estate would be placed into a single Vanguard index tracking fund, with the rest in government bonds.

And here on Monevator we covered how a UK investor can copy Buffett’s simple portfolio when it comes to index investing.

Buffett’s long-term case for investing in shares

In this year’s letter Buffett was more explicit still.

He didn’t just say you could buy via an index fund if you want to invest in equities 1.

He said you should invest in equities via those index funds.

True, Buffett is explicitly talking about US equities.

But I think global equities amount to the same thing as far as his argument is concerned. (Besides, as I said the other day it’s important to beware of home bias robbing your returns as a UK investor).

Compared to cash or bonds, equities are clearly the place for long-term investors to be, says Buffett:

“The unconventional, but inescapable, conclusion to be drawn from the past fifty years is that it has been far safer to invest in a diversified collection of American businesses than to invest in securities – Treasuries, for example – whose values have been tied to American currency.

That was also true in the preceding half-century, a period including the Great Depression and two world wars.

Investors should heed this history.

To one degree or another it is almost certain to be repeated during the next century.”

Of course most people have seen those long-term charts that show stock markets going up over the decades.

So why then do so many of us still horde our money in cash or bonds?

The answer is volatility – both the day-to-day fluctuations in share prices, and the ever-present risk of a stock market crash.

Buffett says:

“Stock prices will always be far more volatile than cash-equivalent holdings

Over the long term, however, currency-denominated instruments are riskier investments – far riskier investments – than widely-diversified stock portfolios that are bought over time and that are owned in a manner invoking only token fees and commissions.”

Of course, you should always have some cash in an emergency fund.

You also shouldn’t be risking money that’s needed in the next 3-5 years in the stock market, given it’s propensity to crash when it’s least convenient.

But beyond that, says Buffett, the key is to distinguish between short-term risk caused by market fluctuations, and the long-term risk of inflation eroding the purchasing power of seemingly safer assets like cash or bonds – as well as the opportunity cost of missing out on the superior returns from shares.

Ignore the market noise

When investing in a pension over 30-40 years, for instance, I think it’s best to invest into an equity-heavy portfolio automatically year in, year out, and to try to ignore the news about the stock market – as opposed to holding a huge slug of safer assets to help you sleep at night while you obsessively track its value.

Buffett again:

“For the great majority of investors who can – and should – invest with a multi-decade horizon, quotational declines are unimportant.

Their focus should remain fixed on attaining significant gains in purchasing power over their investing lifetime.

For them, a diversified equity portfolio, bought over time, will prove far less risky than dollar-based securities.”

Fearful investors in 2008 and 2009 missed out on the buying opportunity of a lifetime, Buffett points out (assuming they didn’t do the only thing worse, which was to sell out of shares altogether and never get back in).

“If not for their fear of meaningless price volatility, these investors could have assured themselves of a good income for life by simply buying a very low-cost index fund whose dividends would trend upward over the years and whose principal would grow as well (with many ups and downs, to be sure).”

Easier said than done – but that’s exactly why you get a better return from shares than from sitting snug in cash.

Here’s what you shouldn’t do

Buffett’s laundry list of bad investing behaviour should be familiar to Monevator readers.

Investors are often their own worse enemies, he says, and they make putting money into the market riskier than it needs to be by turning short-term volatility into longer-term capital reduction through their antics.

Buffett highlights the following investing sins:

- Active trading

- Attempts to “time” market movements

- Inadequate diversification

- The payment of high and unnecessary fees to managers and advisors

- The use of borrowed money

All of these can “destroy the decent returns that a life-long owner of equities would otherwise enjoy” says Buffett, who adds that borrowing to invest is particularly risky given that “anything can happen anytime in markets”.

Obviously I agree with all this, but I don’t suppose Buffett will be any more successful than the rest of us in trying to make people understand that the fact that “anything can happen anytime in markets” is not a reason to avoid equities, but rather a reason to invest in a way that reflects this reality.

In other words, buy steadily and automatically over multiple decades to take advantage of the various dips and to enjoy long-term compounded returns.

Some friends who’ve been asking me about investing since our 20s – and getting the same advice on getting started from me – still begin these conversations with: “Is now a good time to invest?”

Nearly all would do far better never to think about it.

The trouble with active management

Similarly, here on Monevator I forever field questions from newcomers who think it is “obvious” that investing via the more skillful active managers is the way to better returns.

And indeed it would be if (a) the active managers did it for free, or very nearly so, and (b) you could pick those who outperformed in advance.

High fees crush the returns from active managers as a group, turning it into a worse-than zero sum game for active investors as a whole.

As for picking winners in advance, let’s just say many billions of pounds has been spent over the past 50 years trying to do exactly that.

Obviously some do succeed in some particular period, either through luck or judgement. But in terms of a demonstrable, repeatable process that we can use to reliably pick active funds that can overcome their fees and beat the market in advance – sorry, no bananas.

Hence passive investing – wrong as it feels – beats the majority of active investors. So why bother trying, when you don’t need to beat the market to achieve your goals?

But don’t take my word for it when we have one of greatest active investors of all-time on hand to say the same thing:

“Huge institutional investors, viewed as a group, have long underperformed the unsophisticated index-fund investor who simply sits tight for decades.

A major reason has been fees: Many institutions pay substantial sums to consultants who, in turn, recommend high-fee managers. And that is a fool’s game.

There are a few investment managers, of course, who are very good – though in the short run, it’s difficult to determine whether a great record is due to luck or talent.

Most advisors, however, are far better at generating high fees than they are at generating high returns. In truth, their core competence is salesmanship.”

Instead of listening to their siren songs, says Buffett, investors – large and small – should instead read Jack Bogle’s The Little Book of Common Sense Investing.

Quoting Shakespeare:

“The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.”

- Reminder: Equities is just a fancy word for ‘shares’.[↩]

Comments on this entry are closed.

Excellent. WB is also very strong on the foolishness of confusing risk and volatility.

“…………..volatility is almost universally used as a proxy for risk. ………….Volatility is far from synonymous with risk. Popular formulas that equate the two terms lead students, investors and CEOs astray.”

and

“If the investor, instead, fears price volatility, erroneously viewing it as a measure of risk, he may, ironically, end up doing some very risky things.”

Cheers,

Hi Investor,

With regard to the following sentence from today’s blog:

Quote:

Surely if we followed this advive, we’d have been buying progressively more expensive equities for the last six years?

i’ve come to the conclusion that risk is impossible to measure in any reasonably intuitive or simple way.

theres just too many ways things can go tits up

its pretty clear that no-one, no matter how well resourced, is able to do it

i think the trick with volatility is to enjoy the hell out of it while its positive and then to look away and do something else while its negative.

that said – you never know for sure when you might need to sell up – and thats when you will realise there is certainly a potentially unpleasant relationship between volatility and risk

@Paul S — Indeed. Financial types like volatility as risk because it works in equations and because they are measured over the short-term. But quant-types have come along and complained at me when I’ve gone down this path before, so for now I’ll leave it there. (I’m happy to have Buffett as my sidekick on this!)

@The Rhino — For private investors, it’s certainly a personal thing. To give a very trivial example, I wouldn’t have minded if I’d lost everything I had at 25, if the potential reward was worth it. Now, more than a decade on and with a much larger portfolio, I cannot risk it. No single equation/rule of thumb will ever capture all our nuances.

@Summers — It doesn’t matter over the long-term. Imagine you’d been buying “progressively more expensive equities” in the mid-1980s, when the FTSE 100 was around 1000. Who cares, now the FTSE is at 7000? (And you’d have had far, far greater returns still once you take into account reinvested dividends).

Markets go up and hit new highs. It’s what markets do. 🙂 (See the link to “long term graphs” in the article).

@Summers — Also remember that what matters with equities isn’t their *price* but their *value*. Profits have risen over the past 6 years, too, so they are not actually valued that much more highly than in say 2011.

(Certainly they are valued more highly than in 2009 though, but that was a bargain basement time when things looked bleak and very few were buying).

Hello again Investor,

Thank you for taking the time to explain

This old canard trotted out again.

Buffet has achieved financial independence and is worth about 70 bn USD. He advocates putting 10% into short-dated treasuries. That’s about 7bn, or more money than his widow and dependents can sensibly spend in 3 generations. The lesson from his asset allocation is this: — if you’ve made it, don’t ever lose it.

He then has a massive speculative portfolio that he can put into an equity index. (Hell – why not?).

We are not Buffett.

It is a lazy and fallacious argument (appeal to authority if you like classifications) to say that:-

– Buffet has done well

– Therefore Buffet is a genius

– Therefore Buffet’s advice is right

– Therefore if index funds are right for Buffet they are right for me.

Albert Einstein says eat lots of fibre…

Eating fibre and investing in sensibly balances low cost trackers are a fabulous idea, but not because someone said they are. Others have also said that expensive investment managers are a good idea.

This is like the AGW argument. The case for buying n holding trackers is undoubtedly sound, but the arguments in favour of it are so needlessly and insultingly overstated that I find them driving me into the opposite camp. Specifically,

1. As noted above what’s best for Buffett’s estate is no guide to anything else.

2. “Fearful investors in 2008 and 2009 missed out on the buying opportunity of a lifetime”

so what did fearful investors in 1995-2000 or 2006-7 miss out on? If you invested in 1999 you are now just about breaking even with having stayed in cash since then. If the market crashes tomorrow and history repeats itself, that’s a thirty-two year “quotational decline” you have to be ignoring – hardly market froth.

3. “It’s a zero-sum game, to succeed you have to do better than the average”. So it differs how from any other form of human endeavour? If that isn’t a good reason for telling my children not to work their arses off trying to do well in exams, why isn’t it?

“If you invested in 1999 you are now just about breaking even with having stayed in cash since then.”

There’s a certain amount of hindsight and ignorance going on in statements like this:

– You would have been unlucky to buy at the exact top of the market. FTSE100 peak was 6,930 but just 3 months early and you were buying at 6,000. Market timing works both ways — hard to call the bottom of the market except in hindsight. Anyone basing their comparisons with Dec 1999 needs to take a long look at themselves and ask if they are being intellectually honest.

– You would have yielded around 3% in dividends since 1999 which — if reinvested in FTSE100 (with no further tax) would be up about 50% after 16 years.

– If you had a properly diversified rebalanced portfolio across multiple uncorrelated asset classes, you’d be looking at considerably better returns — even if you managed to unluckily start on Dec 31. Typical returns for these balanced portfolios since Dec 99 are 7-10% annual rates: that’s your money doubling every 7-10 years — so perhaps a fourfold return.

I know all this to be true because Gandhi said it was so. (Sorry).

Mathmo – of course there is hindsight involved, my point was that ““Fearful investors in 2008 and 2009 missed out on the buying opportunity of a lifetime” is an equally ridiculous and hindsight-inspired statement.

Yes, I know that the FTSE (or most of its components) pays dividends, I’m a sophisticated investor, me. Re-annualise your 50% after 16 years and tell me how 3.1% outperforms cash over the same period, and how you are being rewarded for extra risk.

@Mathmo — I didn’t just say use trackers because Buffett says so. That part of the article is called a headline.

Below that is another 1,379 words explaining his reasoning / the reasoning.

You might know all this already. Not everyone does.

Presumably you weren’t born with the knowledge so I guess you picked it up somewhere along the way. You might not think Buffett is in any position to give advice about finance and investing, but I’d (whilst snorting) disagree. 🙂

Finally, many people find investing (and philosophy) boring. Figures such as Buffett (and Gandhi) are an accessible way to draw them in.

@R Lee — Regarding your point (3), the issue is that *active* fund management is a zero sum game, whereas general investing is not.

On general investing and zero sum games:

http://monevator.com/is-investing-a-zero-sum-game/

On active investing being a zero sum game:

http://monevator.com/is-active-investing-a-zero-sum-game/

Active investing outcomes are a very different from the situation with your children and most human endeavor.

While a certain amount of intelligence is no doubt innate, it’s demonstrably clear that hard work and repeatedly going to school, paying attention, and passing exams leads to better education outcomes. A better educational outcome in general leads to higher salaries and so forth on average, too.

While I don’t want to get bogged down in how cleaners work as hard as bankers and don’t make as much money and so forth, as a general principle hard work pays in the world of work, too.

And obviously it works in the realms of stuff like building a brick wall. The harder you go at it, the more effort you put in, the faster and perhaps better the wall.

That’s not true of *active* fund management.

There’s no evidence that working harder increases returns for fund managers. As a group, they all work very hard, and as a group they on average fail to beat the market.

There’s even evidence that increased trading decreases returns (although that’s obviously a very imperfect measure of ‘work’ here).

The fact that extra work/effort/cost isn’t rewarded with better results is one of the reasons why passive investing is right for most even though it feels wrong:

http://monevator.com/passive-index-investing-feels-wrong/

WB does not need me to defend him but it should be pointed out that he has never suggested putting 7bn in “cash”. He said that 10% of what he leaves his wife should be put in “cash”.

How much that is is not our business but he has frequently said that all his holding in Berkshire-H will go to charity through the Gates Foundation.

TI – I admire your dedication to the art of the late-night rebuttal. 😉

My apologies if came over a little dismissive but Buffet’s Will has been covered a number of times in lots of places and I think always misses two very Monevator points:-

i) What’s right for Buffet isn’t necessarily right for us: he’s not our financial advisor looking at our situation and tailoring advice to us — he’s in a different place. The journey to FI is about understanding what you need and finding the lowest risk route to get it. Buffet neither did this nor needs this (which is not to detract from what he did do spectacularly well) — he’s also currently about as far on the other side of the FI fence as it’s possible to get from where I am.

ii) We all gasp in wonder at the genius of the 90% in the S&P tracker without looking at the 10% ($7bn) in the short-term treasuries. Buffet knows how to build a brick wall around his wealth — it is no coincidence that the businesses he invests in are those who build brick walls around theirs. His portfolio starts by ensuring that he and his dependants will *never be poor*, then he looks for upside. The Buffet portfolio could be expressed as “put all your FI cash in short-term treasuries and the rest in an equity index”. That looks a bit different from 90:10 for most of us.

PS Gandhi bought TSCO at 170p

Paul S makes a good point that my 7bn is wrong. I’m prepared to speculate that it’s still more than his widow and dependants could reasonably spend.

@Mathmo — Apologies accepted (though that sounds rather grand in this context! 🙂 ) I’m sure you didn’t mean anything particular malicious in your initial comment.

That said I am going to rant some more… 🙂

It’s perhaps hard to understand how dispiriting it is to spend 4-5 hours writing a 1,400 word article, linking it all up etc, after writing maybe 1,000 articles before on this site over 7-8 years covering the waterfront, only to have someone pipe up using words like “lazy”, “fallacious”, and “canard” in response. And even worse when they’re intelligent people who are either factually wrong or who seem to just be expressing the view that they knew this already so please don’t publish such articles, or else they are rare people who don’t like things being put in a human context/on a hook, so again no more of those lazy fallacious articles please.

I’ve written about 200,000 words on investing on Monevator from all kinds of angles. I’ve read all Buffett’s letters, and equally all the big passive investing tomes. I read about 50-100 investing articles a week. The implication that I’ve been struck on the head by an apple on reading Buffett’s words and so I just slapped it out there is just annoying, to be honest, at 1am or any other time. Though I thank you for not being explicitly rude or swearing, like some of the comments I just delete on sight.

Essentially, I don’t know why people bother writing such comments. I probably comment on two articles a year. I’d turn off the Commenting ability here, except that some handful of readers have asked me not to and it’s clearly useful for crowd-sourcing on our broker table and a few other specific posts. But generally it’s just noise, distraction, error, and unpleasantness.

Perhaps 0.01% of readers comment. I doubt 5% of readers read the comments, though I can’t know exactly.

The entire doctrine of passive investing could probably be written on two sides of A4 paper — or perhaps one side if we were to be prescriptive about it (and just say “buy this fund on this platform”, say, rather than trying to add an educational bent).

If we did so we’d have created an elegant little web page that would have maybe 10 readers a month, as opposed to over 100,000 visitors.

Since we are essentially up against a torrent of big budgeted well-resourced media sites where the active to passive article ratio is even today about 100-1, I’d guess, I reserve the right to use any tool I see fit to try to find new ways to get people to (re)consider whether a passive approach is for them.

You apparently grasped the logic of passive investing immediately on encountering it. Clearly most don’t, since we both agree it is simple, and yet the vast majority of people still invest actively.

So unpalatable as it may be to your ascetic impulse, there will be more articles like this in the future. Perhaps articles exactly like this — if Buffett finds a new way to talk about passive investing in the 2016 annual letter, I’ll definitely pillage it again for an article then.

Please do feel free to skip Monevator that day and take your dog for a walk or similar. 🙂

p.s. I knew of course that Buffett was referencing his personal estate, not his investment in Berkshire Hathaway, since amongst other things I’ve tracked how he invests his personal money, and where it differs from BRK’s holdings (e.g. He holds JP Morgan and Berkshire doesn’t). Also, his giving away of his vast fortune to Gates’ charity is among the many things that I admire in the man. But I presumed it was some sort of slip on your part, since you’ve probably also read about that 1000x on the Internet too.

p.p.s. This may sound more ill-tempered than I mean it to. I’m sure you’re a jolly fellow, and shorn of the presumptive comments that you should tell someone else what to write on their site, and the lazy and fallacious bit, I agree with you and even think it was a point sort of worth making, if made in a less affronted tone. But some days these comments get to me (we get loads of comments daily, across old articles and via email) and I’m afraid I’m disgruntled today. Please do have a good evening! 🙂

I am one of the 99.99% who don’t usually comment, but I am part of the 5% who read them – as there’s usually some interesting debate. I’d just like to say thanks to both yourself, and The Accumulator for delivering the stand out investing blog in the UK, not only for being both informative and entertaining on a subject as potentially dry as passive investing, but for the countless hours you obviously put into it with little thanks or recognition. I suspect the 99.99% are hugely appreciative of it even if you don’t hear it anywhere nearly often enough from us.

Thanks. You do a brilliant job.

@Thesquirreler — Thanks for that, very generous!

“There’s no evidence that working harder increases returns for fund managers. As a group, they all work very hard, and as a group they on average fail to beat the market.”

On average, of course they do. On average, there is no point in entering any kind of competition, ever. But some excel, just as someone gets the Olympic gold at the expense of everyone who doesn’t.

That doesn’t affect the overall point which is that it is safer to assume you can’t identify the excellent ones, and shouldn’t try. But it is unwise to overstate cases. If you tell smokers that they all die of lung cancer you just give them an opening to point to their 98 year old etc. etc.

PS Just to reiterate I AGREE WITH YOU, pretty much. I invest 50/50 in trackers, and really boringly blue chip ITs.

@R Lee — I am very close to deleting your comment, basically because it will mislead other readers. There is no way that anyone has ever shown it possible to consistently identify winning fund managers who will beat index trackers over the long-term. (It’s trivially easy to identify them in the past).

This is entirely different from say an Olympic gold medal sprinting winner, who can trivially be predicted in advance from the ranks of the national sprinting champions.

That is the entire point. Sure, try if you want to. I invest actively. But there was talk of ‘hard work’ and so forth here that I was referring to. Specifically, you said:

My bold.

That was the question I was answering. 🙂

p.s. To be clear, I’m not saying I am close to deleting the comment because I don’t think such discussions have value or because your making it is offensive or whatever. It’s just I’ve had these discussions on this site quite literally 500 times. Life is only so long! 🙂

So sometimes I may have to delete just because I don’t have time to explain why what sounds like common sense is actually misleading, yet again.

“If you had a properly diversified rebalanced portfolio across multiple uncorrelated asset classes …”: setting aside the tautology implicit in “properly”, there’s still a problem. We may know what correlations there were among asset classes in the past, but we don’t know what they will be in the future.

I love this site, but I don’t like ding dongs. Please don’t take careless comments to heart; people often say silly stuff, anyone can say any old balderdash, it isn’t worthy of your wonderfully crafted words and precious time. Just a couple of choice but polite words or silence will do; that way you can let others see the folly of their argument and you can devote your energies to another fabulously intelligent yet accessibly high brow financial disquisition.

Thank you for providing an interesting and informative resource. Seems to me that Warren Buffett might justifiably be thought to know more about investing than Einstein knew about muesli. Therefore, his view is not merely irrelevant and can contribute to our understanding, provided one is prepared to explore why he said it and how applicable it is and to what extent true etc. etc.

@Minikins @rick24 — Thanks for your comments. 🙂

TI – my apologies again. I appear to have accidentally hit a nerve with an unnecessarily harsh choice of words which was not my intention at all. Sorry. I think you know the point I was making so I shan’t reiterate it.

I edit and publish a magazine three times a year, so please trust me, I do understand the effort and required to craft articles, and the irksomeness of an ungrateful readership. Yours is an excellent blog on an important topic, and one about which I am evangelical as any convert. Thank-you.

@Mathmo — Cheers, I appreciate that. Let’s move on! 🙂