I am a big believer in setting goals and going for them. (And not only because the alternative of not setting goals, playing Clash of Clans and then falling asleep in the bath is an ever-present default…)

Read any biography of anybody who ever did anything interesting and you’ll find someone who mapped out their aims, set out their goals, and made their to do lists – and then got doing.

And not just hard-nosed but a bit boring businessmen, either.

Below is the work schedule of the novelist Henry Miller, who was once banned as the purveyor of filthy libertine tracts about having short relationships in Parisian public toilets.

Work, Bohemian, work!

I came across this schedule years ago and saved it, and I never again told myself that a free spirit just creates, spontaneously, without thought or planning.

If you’re Mozart, Shakespeare, or Einstein then you can get by without a plan.

If you’re not, make one and regularly review it.

Athletes and entrepreneurs, investors and A-Level students – all can and do benefit from setting goals.

Stepping stones

Goals may seem boring, but they can make everything more fun.

That’s because goals can be broken down into mini-goals, and achieving those can bring their own rewards – even while the main goal remains as distant as Mars to Elon Musk.

If you’ve ever walked in the mountains, you’ll know that climbing a foothill only to see you’ve still so far to climb to the summit isn’t always exasperating – often it’s invigorating.

It’s the same with anything. Break it down, break it down, and then fill your To Do list with ticked off achievements.

When I started Monevator a decade ago, my first financial goal for the site was to make £1 in a day.

It took much longer than I thought it would.

I made my first £1 in a day when I was away in Romania, of all places. I was on the point of giving up writing a website that nobody read.

That was six or seven years ago. I hit my mini-goal, smiled, and carried on.

Goals, fingered

Of course, goals aren’t everything, either, and it’s okay to miss them for good reason, and for your priorities to change.

Just so long as you do so consciously, I think.

Who cares if you never ticked the Statue of Liberty off your New York list because you were too busy romancing your lover in Central Park?

Monevator has been a long tale of under-achievement. It grew far more slowly than my other ventures, the money has always taken longer than I expected, and then some of the money actually went away again.

To be honest I thought by now it’d either be an optional full-time job or else I’d have dumped it for something else.

But after years of working away at something, you discover stuff you never suspected. You may achieve things you didn’t even think of.

Working closely with my co-blogger The Accumulator – who wasn’t around at the start – was not a goal when I began this website. But it has been a highlight.

Also, I’ve never created anything that gets as much positive feedback as Monevator, whether via email or in comments here on the site or from certain friends in real-life.

I didn’t have “receive emails every week from multiple people who tell you that Monevator is what has turned them into investors” as a goal from day one.

Perhaps I should have? It’s been the best thing about the blog, as it’s turned out.

But the targets I did have – articles twice a week, links on Saturdays, and only write substantial posts – kept Monevator going for long enough to discover these other rewards.

Dream on

My Achilles Heel is regularly revisiting goals once I’ve set them – and especially with using visualization to help persuade them into being.

I believe regular visualization is an important part of using goals, however daft and New Age you feel when doing it.

Unfortunately I often feel so daft that I don’t do it at all. I think that shows in some of my weaker results, compared to other goals that have more easily come alive in my imagination.

Creating tangible touchstones and then keeping in touch with them – that’s the real power of goals.

I don’t believe there’s an unseen force in the universe that conspires to give you everything you wish for if only you’d ask, as certain books allege.

allege.

But I do believe that if you concentrate regularly on something, it focuses your talents and your mind on that thing.

You flake out less often. You spot opportunities you otherwise might have missed.

And other people will call you lucky.

Negative imagery and mental beliefs are at least as potent, too.

Recently I’ve been wondering if the reason I’ve never bought that house in London is because I kept imagining myself not buying a house in London?

My self-image is of a canny investor who battles the market and bags bargains. That fanciful image and the London property market don’t mix – or at least not on my budget! Perhaps if you’re a property mogul things are different.

Ironically though, I wasn’t ever really thinking of my potential London house purchase as an investment, although I do absolutely believe that’s what homes are.

I just wanted a place of my own. (Cue strings…)

Maybe if I’d spent more time imagining myself pootling about such a property – and saw my battered leather armchairs, my friends in them, a garden full of herbs, a giant aquarium, a pet tortoise, a fireman’s pole that speeds you from the bathroom to the bachelor den…

…um, well, whatever.

The point is I might at least have bought a two-bed flat in Crouch End.

Bolivian marshaling power

Visualizing goals sounds like a First World problem.

“Deep breath. Now, picture yourself with the perfect thigh gap as you sip your asparagus smoothie beaming with huge delight, while throwing uneaten salted caramel brownies out of the kitchen window into a garbage bin below…”

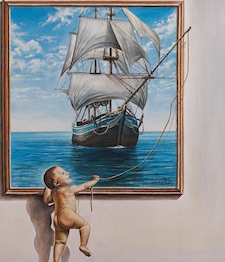

So I was intrigued to receive a gift this week from a friend of mine who is just back from Bolivia:

Not legal tender, even in Bolivia.

As I’m sure you can tell, it is of course a bundle of miniature $100 bills, with some sort of lucky charms attached, all wrapped up with a rubber band.

Ahem. Just what I’ve always wanted?

Well, said my friend, perhaps it is.

It transpired he’d been to the Fair of Alicitas in La Paz, where he’d thoughtfully acquired the mini-money for me from this chap:

This man will officially endorse your ISA. (I don’t know what the frog does.)

That, my friends, is a genuine Shaman. I’ve even seen a video where he blesses my money with some sort of smoky incense before squeezing something out of a detergent bottle over it. Possibly detergent. Hopefully detergent.

According to Wikipedia:

The indigenous Aymara people observed an event called Chhalasita in the pre-Columbian era, when people prayed for good crops and exchanged basic goods.

Over time, it evolved to accommodate elements of Catholicism and Western acquisitiveness.

Its name is the Aymara word for “buy me”.

Arthur Posnansky observed that in the Tiwanaku culture, on dates near 22 December, the population used to worship their deities to ask for good luck, offering miniatures of what they wished to have or achieve.

My friend saw people buying and having blessed everything from mini computers and tiny cottages to scaled down smartphones.

You could even choose between different smartphone brands!

Are the ancient gods of the Tiwanakuns still sprinkling their luck dust over the people of La Paz?

Who am I to say?

But do Bolivians who buy and have blessed a tiny diploma work harder for their degrees?

Do the people of La Paz who put an officially sanctified mini-car of their dreams on their bedside table subsequently skip a few more beers and work a few more extra hours to get the cash together?

And would you be more motivated to save and invest your way to financial freedom if you wrote your goals down, collected together some images that resonated with the life you’re aiming for – whether mid-week walks in the country or a flash sports car as a go-getter – and then studied them once a week, visualizing everything, imagining how you’d feel to have achieved your goals?

In every case I’d bet on it.