Part one of this two-part series explored why the future expected returns of the 60/40 portfolio are unlikely to match the last ten years.

In a nutshell, negative real bond yields plus richly valued US equity markets imply weak capital growth ahead.

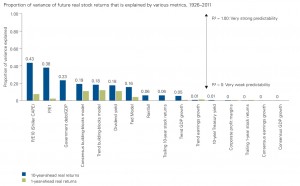

Past experience shows expected returns predictions are more reliable than some chancer with crystal balls telling you that a dark, handsome stranger lies in your future. But not by as much as you’d think.

Still, a deluge of fiscal stimulus and near-zero interest rates has created a sticky financial quagmire. As a result, returns could be muted for a while.

In the face of all this, you can better position your 60/40 portfolio. But there are no magic bullets.

The alternatives come with consequences.

I’ll take you through the non-magic bullets you can fire in a moment.

First though, let’s talk about what not to do.

Don’t buy it

Improving expected returns typically means taking more risk. That’s the trade-off ignored by most of the 60/40 portfolio articles dominating Google.

Here’s a selection of their suggestions for your portfolio:

- Uranium

- Big tobacco

- Russian equities

- Private equity

- Hedge funds

- Timber

- Collectibles

- Music royalties

- Currency trading

- Junk bonds

- Chinese government bonds

- Infrastructure

The correlation between these ideas? They offer hope and are difficult to falsify. So let’s be clear. This is rampantly speculative stuff from the Donald Trump School of Medicine.

These articles are mostly generated by active managers and / or journalists. Their stock in trade is the turnover of ideas, not their quality.

60/40 portfolio: guiding principles

Recall that the 60/40 portfolio’s asset allocation aims to:

- Control risk and cost.

- Be simple to understand and operate.

- Work for investors with little interest in the market’s machinations.

None of those principles apply to the schemes I listed above. Mostly they’re complexity masquerading as strategy:

- Each ‘idea’ increases your exposure to risk and cost.

- They typically involve chancing your arm in opaque markets, which shortens your odds of being the sucker at the table.

- Little to no evidence is given to explain why these options are a good choice.

Sure, a couple of those suggestions may outperform a 60/40 portfolio in the next ten years.

But which ones?

In contrast, the following articles deploy evidence and data to expose how directionless some of those ideas are:

- The track record of hedge funds.

- Same again for private equity.

- Why narrow investment bets are a crapshoot.

- How recurring ideas like infrastructure, timber, and clean energy under-performed the broader market in the past decade.

As for Russian equities – they have been abysmal since at least 2007.

Moreover, autocratic leaders like Vlad Putin and Xi Jinping derive credibility from painting the West as an adversary.

Good luck landing outsized future cashflows as a foreign owner of Russian or Chinese securities.

Ditch bonds

The other ‘big idea’ you hear a lot these days is to drop bonds.

That’s because owning a large holding of government bonds right now is like riding a bicycle with a slow puncture.

But getting rid of them – or even switching up to a 80/20 portfolio? That ignores why government bonds are a mainstay of the 60/40 portfolio.

Holding bonds was never about earning big returns. The point of bonds is to lower the risk of you selling out when stocks crash.

Bailing can permanently damage your returns.

Yet this danger of cracking under pressure is not well understood, especially given how a bull market buries memories.

Panic is an insidious threat because we underestimate it.

Markets can be more brutal than most of us have experienced.

That’s why bonds are still a good investment, even today.

Some commentators state bonds can no longer protect your portfolio, but that’s not true.

These pieces show you why bonds retain some protective power, even at negative rates:

- How bond prices work.

- What bond convexity is and why it matters.

Alright, that’s enough about what not to do. Now for some practical suggestions for 60/40 portfolio investors.

Can you take more risk in your 60/40 portfolio?

The risk of investing in volatile asset classes means the answer to our malaise isn’t: “throw your bonds overboard.”

However, can you live with fewer bonds and more equities?

Can you handle a 70/30 portfolio, for example?

The answer will be very personal.

I’ve previously compiled the best advice I’ve found on risk tolerance to help you explore this issue.

One option is to try an industry-standard, online risk tolerance questionnaire. The idea is to discover the riskiest allocation you can comfortably deal with.

The big debate is whether such questionnaires work. The finance industry has used them for ages. But clearly they’re an imperfect measure.

So only increase your equity allocation cautiously and thoughtfully.

More risk, more reward?

Beyond incrementally revisiting your asset allocation, I wouldn’t recommend making changes on the risky, growth side of your portfolio.

That’s because the other options increase your exposure to investment risk and/or the risk of being ripped off.

For instance, long ago I invested in risk factors. The promise was outperformance in exchange for more risk.

Of course, I knew there was a chance my factor bets would disappoint.

Guess what?

I got the risk but not the reward.

Oh, and let’s shoot another white elephant in the room while we’re here.

The SPIVA study shows that active management is no solution either.

Remember, all the active money in the market – added together with all the passive index funds – is what makes up the market.

That means active management is a zero sum game because when one active fund wins another loses. Or more accurately: when one actively invested dollar or pound beats the market, another must do worse.

Active funds in aggregate can only deliver the market return – minus their higher fees.

The bond trade-off

Is there more you can do with your defensive asset allocation?

Perhaps.

Today’s government bond environment feels like a Tarantino-style Mexican standoff:

- Long bonds are your most potent protector against a deflationary recession.

- But they could inflict equity-scale losses if inflation runs wild.

- Index-linked bonds are your best defence against galloping inflation.

- However they won’t do much in a recession. And their yields are more negative than conventional bonds.

- Short bonds are as much use as a concrete zeppelin in a recession.

- But they’ll do okay-ish if the issue is inflation.

- Cash should be part of your mix, but it isn’t a panacea.

Which way do you turn?

Many fear the return of 1970’s stagflation will financially embarrass us like a kipper tie of woe. Meanwhile, the next recession is a ‘when’ not an ‘if’.

We need a portfolio for all weathers.

An intermediate gilt ETF holds short and long UK government bonds. It’s a muddy compromise that offers decent downside protection in a recession.

And owning some inflation-resistant, index-linked government bonds is de rigueur – even though they are expensive.

I discussed some linker options in this post. (Another global index-linked bond ETF (hedged to GBP) has come onto the market since.)

Fiddling around the edges

Higher-yielding bonds like corporate bonds and emerging bonds are not an alternative to high-quality government bonds in a 60/40 portfolio.

Emerging market bonds behave more like equity. You don’t need them.

Investment-grade corporate bonds offer a little more yield in exchange for less protection than high-quality government bonds.

You’ll probably see owning US Treasury bonds mentioned, too. It’s a decent idea that could offer a smidge of extra return. But it only works under specific conditions. And the risks need to be understood.

You’ll have noticed by now that every ‘if’ comes with a ‘but’.

I prefer to keep things simple:

- Equities for growth.

- Index-linked bonds for inflation protection.

- Cash for short-term needs.

- An intermediate bond fund to cushion stock market falls.

However, I’ve been tipped off about a bond allocation that might work more effectively in the current conditions.

It’s an advanced strategy that requires a good understanding of bonds.

Long bond duration risk management

One logical response to a low yield world is to make like American politics and move to the extremes.

That means replacing intermediate and short bonds with long bonds plus cash.

This barbell approach hopes to capitalise on:

- The slightly higher yields of long bonds.

- Their better track record in recessions, relative to other bonds.

- The low duration risk of cash. This offsets the vulnerability of long bonds to rising market interest rates.

Here’s an example:

Desperate Daniella holds 100% of her bond allocation in an intermediate gilts fund with a duration 1 of 10.

She replaces that fund with:

- 50% Cash (duration 0)

- 50% Long gilt fund (duration 20)

Daniella’s reallocation still leaves her with a weighted duration risk of 10:

- Duration 0 x 50% = 0

- Duration 20 x 50% = 10

The long bond duration risk is dampened by the cash.

This is not a free lunch. It gives you greater exposure to the longer end of the yield curve. That could be hard to live with should that part of the curve steepen in response to, say, spiraling inflation.

The idea comes from Monevator reader and hedge fund quant, ZXSpectrum48k. I’ll refer you to some of his comments on the topic:

What about gold in the 60/40 portfolio?

From a strategic perspective, the best thing going for gold is its zero correlation with equity and bonds.

Gold randomly does its thing like Michael Gove in a nightclub – spasming erratically regardless of the drumbeat moving other assets.

Gold did amazingly well in the stagflationary 1970s. Back then equities and bonds got hammered. However, one-off historical factors were in play. The US Government had stopped fixing the gold price and legalised private ownership.

The yellow stuff smashed it during the Global Financial Crisis, too. But gold cushioned portfolios less successfully than gilts in the coronavirus crash.

And gold lost 80% between 1980 and 2000.

So no, gold isn’t a no-brainer. You still have to use your nugget. (Alright, that was just gratuitous – Ed).

Some model portfolio allocations like the Permanent Portfolio and the Golden Butterfly include a generous dollop of gold. How clever that looks depends mightily on the timeframe you pick.

Meanwhile, gold’s long-term return hovers right around zero. It’s crock-luck as to whether gold will work for you. The hope is it comes good when everything else fails.

For me, this boils down to a 5-10% allocation in a multi-layered defence.

Where does that leave the 60/40 portfolio?

We live in interesting times. Diversification remains the right approach.

The all-weather portfolio below is positioned for uncertainty, without sacrificing the principles that first made the 60/40 such a godsend.

- 60% Global equities (growth)

- 10% High-quality intermediate government bonds (recession resistant)

- 10% High-quality index-linked short government bonds (inflation hedge)

- 10% Cash (liquidity and optionality)

- 10% Gold (extra diversification)

This asset allocation maintains the 60/40 portfolio’s balance of growth and risk. Granted, it adds complication. But every asset has a clear strategic role.

That makes more sense than knee-jerking into private equity and uranium.

Remember the 60/40 portfolio was never a get-rich-quick scheme. It gained traction because it was good enough.

For more:

- How to protect your portfolio in a crisis.

- More on defensive asset allocation.

- An easy way to move to a 70-30 portfolio.

- Why you should use short-dated global index linked bonds hedged to the pound. Part one and part two.

High-quality government bonds means gilts or a developed market government bond fund hedged to the pound.

Taking control with a 60/40 portfolio

The more effective countermeasures you can take are technically simple but emotionally difficult.

You can’t control future asset returns. But you can control these mission-critical factors:

- Contribute more money to offset lower growth expectations.

- Increase your time horizon to benefit from compounding.

- Lower your financial target to make it easier to hit. That ultimately means living on less, if we’re talking retirement.

To see what a difference this makes, run your numbers in a calculator like Dinky Town’s Retirement Income Calculator.

Adjust contributions, income target, and time horizon to suit your circumstances.

See how things look under a range of expected return scenarios. Try plugging in optimistic, pessimistic, and middling predictions.

For example, these expected return forecasts come from Vanguard:

- Optimistic: 4% (75th percentile)

- Mid-ground: 2.6% (Median outcome)

- Pessimistic: 1.2% (25th percentile)

Those are 10-year annualised expected returns for three alternative universes.

To turn those into real returns, I’ve subtracted an average annual inflation guesstimate of 2% from Vanguard’s nominal figures. 2

Put the expected returns into the calculator’s rate of return field via the Investment returns, taxes, and inflation dropdown.

Periods of lower (higher) returns tend to be followed by higher (lower) returns. Accordingly, you can hope for improved growth beyond the next ten years. The Dinky Town calculator lets you play with that, too.

The three most powerful changes you can make are putting more money in, waiting a little longer, and lowering your income bar.

They also save you from meddling with your 60/40 portfolio if that suits your risk tolerance.

Not-so-great expectations

Multiple crises over the past 15 years have trapped us in an escape room with no easy way out.

I wish there was a clear answer to this puzzle but there isn’t.

Taking action now means short-term pain for long-term gain.

On the other hand, what if the next decade exceeds expectations?

Hallelujah! We’ll be better off than we thought – living on more or retiring earlier.

In conclusion: fingers crossed.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

Comments on this entry are closed.

Great article

Past the time for me taking risks-aged 75

30/65/5 does it for me with 3 index funds only ie equities/bonds/cash

Tried and tested through lots of ups and downs and over many years

Of course it may be different this time but I doubt it

Getting ready to spend less?-Covid helped with that so far!

Very boring but getting your excitement elsewhere than the stockmarket is a good plan!

xxd09

I happened to get a Vanguard forecast graph for a 60:40 portfolio pop up in my email in-box at the weekend. https://www.vanguardinvestor.co.uk/articles/latest-thoughts/markets-economy/market-forecasts-matter?cmpgn=ET1021UKCENLP0104 It differs slightly from the figures you give, but those might be real returns and the graph in that link actual returns (and imply an expected annualised inflation rate of 1.2%). Either way round, the expectation is less growth in the future than we have become used to.

So the question is whether the changed risk:reward ratio remains worthwhile. Systemic risk is mitigated as far as anyone can by diversification anyway and is unchanged; volatility risk is what you are trying to reduce with your adjustments to the bond component. How much would your proposed mix have reduced volatility (and affected yield) over the last 10 years compared with a typical bond element?

To some extent, what is acceptable in terms of risk:reward depends on what alternatives are available. And we are conditioned by recent experience of what I suspect is relatively low volatility in historic terms.

@xxd09 (#2):

Cheeky question – do you really think you might need to spend less than you did in pre-covid times?

Thanks again @TA for another informative and interesting article.

Aged 36, probably on about 85/10/5 equity/bond/others, inc cash, commodities, a very tiny bit of blockchain, approaching 3 figures, with a saving rate of around 30% at the moment, which is high in equities but I’m comfortable with at this stage, regardless of anything looming (who knows, I don’t – likely moving house in the next year or so, so starting to lean towards more cash for that). Will likely start adding to a Govt bond etf down the line.

Still transitioning my ISA portfolio away from individual shares and managed funds into a majority led index approach, but recently sold a RL index bond (I think the as same listed in the S&S portfolio) and put into a VG LS 80% – which is and will forms the core of my holdings. Wasn’t convinced I needed both the bonds in the RL fund in addition to LS80 rather than any wider situation. Craving simplicity, just aim to keep mainly adding to VG LS 80 for another 15+ years or so before thinking about changing down to 60 or a mix of the two, while in the meantime adding smaller amounts to investment trusts to satisfy my active cravings. (aiming for something like 75% of my S&S SA in LS 80, plus small-cap and property index – the two smaller index funds being no more than 10% of this, with the rest in a small range of investment trusts for income and growth.) Rebalance once/twice a year. Trying to be disciplined, doesn’t always happen.

SIPP and Lifetime ISAs have smaller amounts, but all passive index fund such as L&G Future World 5. Just add and leave for those. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

Damn typo – meant total portfolio approaching 6 figures, blockchain (BNY blockchain fund, less that 0.5% of everything held)

Al Cam

Spending 70% less than previously

No foreign holidays.Daughter currently in Rome with husband and 3 kids

Watching to see how it goes-then we are off again!

xxd09

@TA – Thanks for for this. Still all a bit hazy to me to be honest. I’m tempted to just move all my VLS 80 allocation to VLS 60 + HSBC Global Strategy Balanced + L&G Multi Index 5 + Cash. All simple and pretty much middle of the road. I’m not looking for mega growth anymore so as long as I can get 3%+ I guess I’ll take it.

@ssdo9 – if your 3 ETF portfolio is fully tried and tested then that seems as good a recommendation as I’ve heard so far. All that we need to know is what the 3 ETF’s are?

Great article. Any thoughts on investing in a fund which holds floating rate notes? That way if rates move up you earn more and don’t get wacked like you do on long dated bonds?

Chris

Vanguard Developed World ex U.K. VVDVWE- 27%

Vanguard FTSE AllShare Index. VVFUSI-3%

Vanguard Global Bond Index Fund hedged to the Pound VIGBBD-65%

xxd09

@TA — Thanks for writing this and many other excellent pieces! Adding assets like gold and index-linked bonds seems prudent for wealth-preservers/decumulators. But what about accumulators?

More specifically, let’s say someone is doing the “diligently-save-two-thirds-of-your-salary-for-however-long-it-takes-to-hit-FI” thing. Let’s also say, hypothetically, that that this person:

1) has an iron-willed ability to avoid selling equities during a market panic/downturn; and

2) optimistically hopes that the journey to reach FI will take around ten years, but has the flexibility to wait a few extra years if necessary.

In this scenario, is holding assets like gold/index-linked bonds best seen as an insurance policy that increases the odds of hitting FI in a reasonable time-frame? Or does it more likely cause a long-term drag on portfolio returns that delays the path to FI?

I think 100% equities is by far the best path for someone in the accumulation phase who can control their actions when the market crashes, which any mature reasonable person should be capable of doing. But that is while accumulating and building a portfolio, once you’ve won the game and are a few years out from retiring then 60-40 is a very valid strategy. At that point you should have plenty of invested assets and should not need a lot of growth. At least that is the plan I followed with 100% equities for most of my career and then shifting to 60-40 a few years away from retiring early. Six years into retirement I’m at around 55 stock, 35 bond and 10 cash. I don’t need growth now, so I prefer the calmer nature of a balanced portfolio.

Thanks for another great article, I love your writing style. After reading, my conclusion was that we should just stick with the 60/40 portfolio and weather any storm.

“The three most powerful changes you can make are putting more money in, waiting a little longer, and lowering your income bar.”

This suggestion holds true for any situation or circumstance, and it’s hopefully what we’re all already doing. There is no downside, it’s a ‘get out of jail free’ card.

As a younger (ish!) investor, I love and crave the simplicity of the pathway ahead of the fund-of-fund accounts (even if my brain or the news try telling me otherwise), the only decisions being how much to put in on a regular basis (monthly Direct Debit) and when to rebalance/make the decision to switch, ie gradually moving from Vanguard 100, through to 80, through to 60 as time passes (still 15+ years for me in accumulation at least I reckon). Same with the HSBC or AJ Bell passive funds, moving down from their Adventurous down through the ranges of Balanced and Cautious etc.

Sorry, but I’m still not buying it regards the bonds.

“The point of bonds is to lower the risk of you selling out when stocks crash.”

Really…? Frankly IMHO that’s not a good enough reason for a 40% allocation.

So here’s my take: (1) look at how long your favourite equity index (e.g. MSCI Global hedged to GBP) stayed down during the big historical market crashes. (2) multiply that number by however much you want in order to feel safe. (3) Work out what your annual household running costs would be over that duration. (4) Hold that much in gilts or treasuries – maybe 50% as inflation linked.

How does a bond fund like vanguards VAGP (gbp) / VAGF (eur) fit in?

I have 10% allocation to it currently. I want to have about 20% in bonds but not sure whether to add more to it or to something else like pure government bonds (euro) or something index linked?

Thanks @TA for this article. I always feel I learn something. I definitely don’t feel in control of this stuff and I am conscious of too much tinkering, so I’m definitely happy with the LifeStrategy approach for now.

I will continue to focus on those areas where I do have a fair amount of control:

1. Understanding my relationship with money

2. Reducing my expenses

3. Saving more to lower my WR

4. Working to identify a fun long term additional income stream so it’s not all about my investments.

@xxd09 (#6):

70% less is quite something! This report from the ONS might interest you:

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/expenditure/articles/weeklyhouseholdspendingfellbymorethan100onaverageduringthecoronaviruspandemic/2021-09-13

Al Cam

Apologies -phrased that wrong

Now spending 70% of previous income!

Incipient Alzheimer’s?

xxd09

For me the simplicity of an index fund and the effect on investment behaviour is one of the things that is seldom mentioned. By that I mean for me it was the first time I felt like I ‘got’ investing and completely changed my view point from ‘hold mostly cash and use say 25 % to gamble on the markets to’ hold 6 months cash and leave everything else invested

I also think alot of people are like I was 8 years ago (embarrassingly given I’ve always been obsessed with this stuff and also work for a financial services company! ) and not realising a pension and a s and s isa are just different sides of the same coin. You ask the average person about investing and they’ll say they don’t as it’s too risky but almost everyone now is given auto enrolment but they just don’t equate the two.

And at age 40 I’m in the 100% equities camp planning on changing to a ladder approach when I retire – 2 to 3 years in cash a further chunk in say a 40/60 fund for 5 years spending on top and the rest left in equities

@xxd09 (#18):

Got you – and much more in line with the ONS findings. Thus, I suspect you probably will not need to spend less than you did in pre-covid times.

@ Wodger – the article holds for accumulators. What matters is your assessment of the risks you personally face. I understand the spirit of your hypothetical but for me the problem is… We just can’t know how we’d react in extremis.

Picture the scene: you look back at market history over the last couple of decades. Sure, the market goes down 30-50% but recovers pretty fast – within a couple of years. OK, sounds rough but we can deal. So you follow the prescription of ‘100% equities and then just glide home a few years before FI’. You plan to shift into 30-40% bonds once you’re in wealth preservation mode.

But events don’t follow the script. The market crashes after you’ve accumulated significant wealth but just before you can shift into bonds. Bonds are up. Equities are down. Way down. The market gets cut in half. Then it gets cut in half again. You’re down over 75%. This time there’s no V-shaped recovery. It’s an L. A decade later equities haven’t recovered…

This and worse has happened over the last century. The idea that the market will deliver solid equity returns then allow us to smoothly shift to wealth preservation at a time of our choosing – this is wishful thinking based on the experience of the last decade. We can’t rely on that pattern repeating.

Re: your question about insurance policy: Over the long term you’d expect equities to outstrip gold and index-linked bonds. But anything can happen in a decade. If gold or linkers outperfom equities over the next 10 years then that insurance has paid off.

Probabilistically, you’d expect equities to be the best performer. Hence its asset allocation dominance. But an allocation to defensive asset classes acknowledges that there’s also a probability equities don’t deliver.

As an aside, what often seems to get missed is that equities generally do poorly when inflation is unexpectedly high. Equities outstrip inflation over the long-term but can be hurt badly by high inflation over shorter time periods like a decade. Some allocation to index-linked bonds therefore makes sense to me for accumulators.

@ ADT – cheers! I think you’re spot on highlighting that part of the piece.

@ JDW – You’re plotting a sound course – our own brains and the news can be our worst enemies.

@ MJ Cross – Your idea works as long as you accept that your equities could be down well over a decade in real-terms. Also, I thought I was pretty clear on alternatives to holding a 40% allocation in nominal bonds.

Finally, I wonder how we’d feel if equities lost over 70% in 18-months: https://monevator.com/the-uks-worst-stock-market-crash-1972-1974/

@ Latetothegame – I doubt there’s a huge amount in it. You get a little less downside protection in exchange for the diversification. Index-linked bonds diversify you against a different threat – runaway inflation.

@ never give up – that’s a brilliant response.

When people talk about a 60:40 portfolio (or any of the other variations), are they generally talking about the constituents of their pensions, ISAs or everything combined? I would just be interested to know what people class as their ‘portfolio’ as, personally, I am more likely to think about the make-up of my SIPP and ISA separately, rather than as one combined ‘fund’ (due to not being able to access my SIPP for some time, I feel like I can be more aggressive with it).

@TA Great article as ever. I’m afraid I’m in the same camp of some of the other commentators on the 40% bond allocation though – I’ve never seen the need, and don’t anticipate this changing until I’m pretty close to retirement (when I’ll need a glide path to a 30-40% bond allocation, to manage sequence of returns risk). As you say, everyone needs to determine their own risk appetite, though I do think the calculus was different when bonds had a decent real yield.

You pointed out in the first article that one problem with the 60/40 is the large exposure to the very highly valued US market. I understand why you don’t advocate doing anything about that in this article – it would depart from both the simplicity of the 60/40, and the orthodoxy of the market portfolio. Not knocking that given what you’re trying to do. But FWIW I’ve done a “roll your own” global portfolio by investing in a bunch of regional and single country ETFs, with the weighting based on valuation grounds. Simple it ain’t, and of course there is a slightly higher cost than holding a single world ETF. But I like it.

We tend to think “how would I react to a 50% drop in equities” and we may feel we could stomach it. We ought to also think how our partners might react. Holding my nerve while my other half is screaming at me to sell the other 50% before I lose the lot, accusing me of already having lost half of her savings? That’s a different ball game…..

@The Accumulator

>> An intermediate gilt ETF holds short and long UK government bonds.

Could you possibly name some names please? The site and comments always have a great range of suggestions for various Global Equity ETFs, but I rarely see any suggestions for (say) a trio of Gilt ETFs.

Thanks

@ Valiant – good point.

@TA – what would also be of value to many of us (IMO) would be some suggested core portfolio’s based on your thoughts and ideas mentioned in the two articles. Maybe you could revisit the article you produced (can’t remember it’s name) where you put forward several core portfolios based on where you might be on the journey to FI. You gave them each a name at the time. The only one I remember is the Silver Fox (cos that’s me).

I just started a new job, and the group pension scheme is with L&G.

The company has selected the ‘Multi Asset 3’ fund as the default fund which is about 40% equities, with only 7/40 of that in US equities. The other 60% is mostly a mixture of corporate and sovereign bonds and property exposure.

The wealth generation left on the table by leaving your money in this fund is rather stunning. Over the last 5 years this fund has annualized 7%, which sounds great, until you look at the FTSE Global All Cap index which annualizes to 12%!

It’s easy to say “100% equities is a bad idea”, but over 25 years an annual performance gap of <3% will easily give you 50% downside protection.

Mark C-Interesting point

I have long regarded my and my wife’s SIPPS and ISAs as the “Portfolio “

It was difficult enough running 4 investment vehicles without trying to maintain the required Asset Allocation in each separate vehicle

So “Portfolio “ is regarded as one unit re my desired Asset Allocation

This becomes especially true as one enters drawdown where one is pulling from SIPPs or ISAs or both

xxd09

Nice duo of articles. Still not convinced about having a high allocation of bonds (due to things not encouraged for discussion on Monevator), but will go over the links provided on them again.

Comparing Private Equity with Uranium is a bit off. As pointed out in the comments of part 1, the Private Equity ETFs mostly contain firms which invest in P/E, Real Estate & Infrastructure. So that’s more diversified than REIT ETFs…

One sees figures given for YTM on IL Bonds. On what basis are these calculated given that the future interest paid will inevitably change as the inflation rate change? Does anyone know?

@xxd09: it might be valid to consider all the SIPPs and ISAs as one portfolio for asset allocation – I try to do this too – but it shouldn’t necessarily mean that the allocations *within* each individual one should be identical to the consolidated one, as the tax treatments for each are different. For example if you had a 60/40 approach and either SIPP is closer to the Lifetime Allowance you might want to have more of the “40” in those, because the upside would be so heavily taxed.

@Algernond: for the benefit of us sporadic visitors, what are the issues that argue against a high bond allocation to which you refer please?

@Mousecatcher007: interesting question. I have no idea either. To speculate, might it be that just the non-index coupon price is used, on the assumption that everything that is known now about the likely future inflation rate is already built into today’s price?

@ c-strong – That’s completely fair. You’ve considered your risks and come to a conclusion that works for you. That’s all I’m arguing for 🙂

If anyone thinks I’m shouting: “Give me the 60/40 or give me death!” then they’ve got me wrong.

You’re absolutely right to highlight that simplicity is a key advantage of a 60/40 type portfolio. Over time I’ve come to realise that simplicity has a value all of its own.

It’s just too easy for people to bandy around ideas like ‘Chinese bonds this’ and ‘uranium that’ without acknowledging the risk that this stuff fails to beat a standard index tracker. These pieces were about those risks realised:

https://monevator.com/portfolio-case-study/

https://monevator.com/10-year-retrospective-investing-in-the-future-with-specialist-funds/

@Windinthefens – that’s a great point. I know a couple who did that recently. Either one of them may have stood firm individually but together they drove each other to a panic.

@ Valiant – sure thing. We keep a list here:

https://monevator.com/low-cost-index-trackers/

Specifically on bonds:

https://monevator.com/best-bond-funds/

@ Mark C – best practice is to consider every account that’s funding one financial objective as a single portfolio. For example, if your ISAs and your SIPPs will sustain your financial independence then that’s one portfolio. If another ISA is intended as an emergency fund or to fund kid’s uni fees then that’s another portfolio – probably with a different asset allocation. More detail here: https://monevator.com/multiple-portfolios/

@ Chris – ha, I trust you’re a silver fox in both finance and exploits 😉 That’s a good shout. It is time to update one of those pieces.

@ Andrew – I’ve seen some stunningly rubbish default fund’s in workplace pension schemes. I have to disagree though. When I cast my eyes around the gobbier parts of the internet, it’s all too easy to say: “100% equities is a great idea,” based the last decade as proof of concept. To paraphrase Jeremy Grantham: In the short term [we learn] a lot, in the medium term a little, in the long term, nothing at all.

@ Algernond – For clarity, I’m not comparing private equity with uranium. I’m pointing out that these ideas are tossed out there by mainstream media with next to no consideration of the risks or suitability for ordinary investors.

Three reasons: It sounds sophisticated, they have something to sell, people read it.

David Swenson – the Yale fund manager who helped popularise private equity – went to great lengths to explain that information asymmetry made asset classes like P/E unsuitable for ordinary investors. As it turned out, most of Swenson’s highly-resourced peers couldn’t replicate his returns.

I’m not here to rubbish asset classes. My role is to point out the risks and extra care needed by ordinary investors if you venture into more opaque markets.

@ Mousecatcher – See: https://monevator.com/bond-prices/

@Valiant — @Algernond is being respectful of the comments and discussion policy here on Monevator, for which I thank him. 🙂 Let’s just say a non-mainstream view of political and economic developments. If you fear true hyper-inflation, for example, then you don’t want to own bonds, they’ll be wiped out.

p.s. To clarify I mean vanilla fixed coupon bonds, not inflation/index-linked government bonds, obviously. 🙂

Good point Valiant

If getting near LTA in a SIPP then keep the bond part of your portfolio there

Unfortunately never reached that position myself!

xxd09

@TA #21 — Thanks! You’ve convinced me.

When researchers like Big ERN run simulations of portfolios or glidepaths using historical data, they arguably focus too much on the distribution of possible outcomes, and not enough on what would happen if the very worst came to pass. I suppose it’s safer to be overly-pessimistic.

However, if it’s wishful thinking to assume that can effortlessly shift from equities into bonds as you approach FI, why not transition between these two extremes in a more gradual manner?

This would recognise that when you’re just starting out on your journey (in terms of both net worth and years ahead), you can afford to be more adventurous, but that by the time you’re closing in on your target, you should already have a much more resilient portfolio.

I could envisage a mathematical model incorporating variables like current net worth as a multiple of your monthly contributions, your target FI number, and expected returns. You could then use this to adjust your allocations every month/quarter/year as desired. Has anyone formalised this kind of calculation?

Hmmm. I just realised that I re-invented target date funds! Nevertheless, this kind of glide-path would look quite different for someone following an accelerated FIRE strategy, especially if they want to eventually shift into other defensive asset classes.

@Wodger. I think you need to be careful about getting bound up in models. ERN’s modelling is simplistic but if you ramp it up you’d quickly hit an issue with having to make far too many assumptions.

Instead spend more time on working out your objectives. The aim of an investment strategy is then to hit those objectives with the lowest probability of failure. If the aim is to build a portfolio of value P, the the a strategy that will generate on average 1.25xP with an average shortfall of 10% is far superior to a strategy that will on average generate 1.50xP with an average shortfall of 30%. You score nothing for generating 3xP, you lose if you generate 0.9xP.

Endowments understand this very well. They are the masters of dampening path dependence and sequence of return risk. Commentators like Swedroe always moan that endowments could be making higher returns if they just bought more trackers etc. Yes, equities outperform pretty much everything over the long term. We all know that. Endowments know that. It’s just it’s not compatible with their objectives. It’s not their job to outperform or maximize returns. It’s their job is not to fail.

This is something that seems to get lost. In investment, winning most of the time is the default position. It’s understanding how not to fail that is hard.

One thing I’ve learnt in over twenty years of investment is that you always want options, you want to hold the initiative. You never want to be in a situation where the only choice you seem to have is to stop-out or pray. Neither hope nor belief are investment strategies.

So diversification isn’t really about optimizing the variance-covariance model so that you sit on some efficient frontier. It’s just about having those options. Own a bit of everything, even the stuff you don’t like. When stuff goes up like a rocket, trim it but never sell it all. When it goes down add a bit but never go all in. Markets are stochastic, they love to mean revert. So make volatility your friend, not the enemy.

@accumulator – great article. On Index linked bonds I thought that elsewhere you had pointed out that they are problematic in the aim of hedging against inflation. They are at best a protector only against *unexpected* inflation. They are possibly overpriced because of the regulatory requirement for pension funds to hold them. Also they have very long duration they may paradoxically not provide much portfolio protection in an inflationary surge. I haven’t looked in detail for a year or two but have I misunderstood earlier comments or has the situation changed?

@mjcross – I think you’d end up holding rather more bonds than you might anticipate.

So the iShares MSCI AWCI ETF on, say, 31 March 2000 reached 1771. It then fell for 30 months to September 2002. It then took 4 YEARS to recover to 1771… So 6 and a half years of income in bonds. Now, if I’m (naively) using the 4% rule, that’s eaten a quarter of your portfolio. But just as you get even in October 2006, the GFC happens a year later so you need another 58 months of bonds (call it 6 years) to get you to August 2012 before the index is (and has stayed) above this level.

So over 12 years of bonds. Say 40% of your portfolio?

And these are nominal returns with dividends reinvested (but zero return on bonds which, from our present situation, isn’t unreasonable). And massive (and ongoing) QE post-GFC. Can this be repeated? Effectively, with that money still pumping up asset prices?

Me? I’ve got enough bonds, gold and cash to last me (just!) till my DB and state pensions kick in when they’ll fill that role. I fully expect the next recession to be a long slow grind, rather than a nice, short V. But I know nothing, so am holding 20% Gold, 10% short inflation linked govt. hedged bonds, 20% intermediate US Treasuries (unhedged) and 5% cash in my reverse glide path to 70:30. But I may end up eating them. Or not, who knows?

@TA – another great article. I moved my hedged global intermediate bonds to inflation linked ones after your first article as I didn’t think I had enough inflation cover in the medium term. Got ii to list GISG as they only listed GIST when I tried to buy. I’ve got growth (global equities), inflation (linked bonds and maybe gold), recession (intermediate Treasuries) and “stuff” (gold) covered.

I went from 100% equities in November 2019 overnight to 40:60 so I’ve missed this big upswing. But I’m happy I’m now prepared for the worst, even though I know I’m missing these gains I’ve got enough. As I get closed to FI(RE), my risk appetite has diminished somewhat 😉

What’s the best options for gold? DigiGold looks very convenient, and I think is exempt from CGT. Maybe a bit expensive though.

@Adrian — All that is true. But we might have *unexpected* inflation, hence why @TA advocates holding some.

As @ZXSpectrum48k says, in an ideal world you want to own a bit of everything. We’re fallible. Markets are volatile.

You’re basically trading opportunity cost for lower risk like this.

Thanks @ZXSpectrum48k. Your arguments (and The Accumulator’s) have definitely changed my perspective on managing risk in the accumulation phase. It probably pays to be a pessimist in this game!

What would be a recommended sensible course of action for a workplace pension fund? I’m mid 30’s and have started taking an interest (better late than never) in what my pension is invested in. I didn’t like the default fund so have restyled it as a DIY global equity tracker. Good start.

I keep getting told that at my age I should ignore bonds for now and stick with 100% equities however I have the constant nagging feeling that I should at least hold something for diversifications sake.

I don’t seem to have many attractive funds available though. My options for reasonably priced funds are UK Gilts and inflation linked gilts trackers, either 5 years and longer or 15 years or longer. Nothing global unless I want to go with an expensive active fund. I can get the Lifestrategy funds so perhaps Lifestrategy 20 to get some global bond exposure? These will cost my 0.58% a year though.

Am I overthinking things?

@Dan – probably 🙂

If it’s in a pension and you won’t be able to access for 30 or so years, I think just make a start. at the lowest cost you can. Which you seem to have done. You probably don’t need bonds if you’ve 30+ years, maybe in 15/20 years have a re-think? Suerte!

@Brod

That’s what I thought! Perhaps I should put as much effort into not reading so much financial and investing news and articles on the internet. I think I’d be alot happier and less stressed about these things!

I would like to add some inflation linked bonds to the defensive part of my portfolio.

Any thoughts on these?

ISIN LU1650491282

ISIN IE00B0M62X26

ISIN LU1390062245

ps. thanks for previous reply!

@ Chris 26

https://www.google.com/search?q=site%3Amonevator.com+“silver+fox”

https://monevator.com/asset-allocation-types/

Valiant

Another good point re varying and variable constituents of various savings vehicles especially over time

Certainly regarding them all as one simplifies everything

Keeping to ones desired Asset Allocation over the “Portfolio” is hard enough without having to replicate the same Asset Allocation in each savings vehicle

Probably impossible for the average investor!

xxd09

Are there any sensible options for people using a Vanguard ISA considering the only inflation linked bond fund on their platform is a UK gilt fund? Is it just a case of 50/50 standard/inflation linked bonds with a bit of cash?

Dan-bonds are there to control volatility in your portfolio

The income they also produce is a bonus but a secondary effect

Equities do the growth

So young investors should have a high % of equities

Once you have saved a reasonable pot then some bonds are sensible to avoid those stomach churning market drops

A rough guide is your age minus 10 in bonds

It’s all very personal and so dependent on individual circumstances

Bonds are complicated-much more so than equities

Personally I use one fund only-Vanguard Global Bond Index Fund hedged to the Pound for my bond allocation of my portfolio

xxd09

@xxd09

Thanks for the reply. I think perhaps my comment was worded badly, I meant for the defensive portion of my ISA going 50/50 on the 2 types of bonds.

Currently in my ISA I’m actually 70/30 equities/bonds as this is a pot of money that I don’t think I could really stomach seeing plummet in value, but I still want some growth from. I have no plans fo the money short term, have my emergency fund and cash savings etc. I’ve read Investing Demystified and Lars K recommends using Govt bonds from your home country as the safe part of your investments. Now I prefer the idea of global diversification so at the minute my 30% allocation is split 10/10/10 Global Bond Index/UK Govt. Bond fund/Cash due to being totally unsure what to do.

It’s messy and I don’t like it so perhaps (same as with my pension question further up) I should just stop overthinking it and stick the 30% in the Global Bond Fund and leave it alone!

@ZXSpectrum48k (Comment 37). Thank you for that comment. You have nicely crystallised some of my own concerns/thinking. The name of the game is to reach your objectives. Not to fail. Anything you gain above that is nice to have, but not the purpose of the exercise.

Also agree with @Windinthefens (24). An equity plunge would freak out my partner, so her ‘share’ of our investments is very, very defensive.

@ Adrian – The index-linked bond problem seems to specifically affect the index-linked gilt market. So the trick is to go with a shorter duration global index-linked bond fund hedged to GBP. There’s a couple of links to a more detailed discussion some possible candidates in the paragraph above the Fiddling Around The Edges subhead.

Linkers are the best protector against unexpected inflation – by which we mean inflation that the market underestimates. In other words, linkers will be your friend when the market is under-forecasts inflation.

Guarding against unexpected inflation doesn’t mean linkers won’t work just because the world fears inflation right now.

Think of the ‘unexpected’ in this context as equivalent to a share price dropping after reporting huge profits – but profits that were lower than market expectations. Bad news on inflation is good news for linkers, generally. That was really long-winded and my apologies Adrian if you knew all that already.

Anyway, a global linkers fund is a workaround for the problem you specifically asked about. My problem: verbal diarrhoea.

@ Wodger – Agreed, it’s better to think in terms of gradual and habitual transition from equities to defensive assets, rather than ‘one day I’ll throw a big switch and hunker down’.

@ Brod – nice work on nudging ii. Good to know they’re responsive. I felt the same drop in risk tolerance as you as I transitioned from accumulation to preservation.

@ Dan – you don’t need global bonds on the nominal / conventional bond side. They’re doing the same job as gilts, so you can pick one or the other as long as the global bonds are hedged to GBP.

Your ISA’s 70% equity allocation is pretty adventurous if you’d be upset to watch it drop like a stone in a market crash. For simplicity sake, take the ISA’s current value and model how it falls if you halve the value of the equities and the bonds stay flat. If you can’t live with the result then go for a lower equity allocation.

There’s no alternative linker option on the Vanguard platform. You could open an ISA on another platform but it may not be worth the hassle. Depends on the size of your holdings.

Yes, many people just split the difference and go 50:50 linkers, conventional bonds.

@ Latetothegame – Those ETFs could be relevant if you pay your bills in Euros. See the links I mentioned in my reply to Adrian for broader discussion applicable to UK investors.

Thanks to ZXSpectrum48K comment 37, this sums up the portfolio question incredibly well, the balance of greed and fear, our irrational dislike of some assets, focus on the objective. lack of money is a real problem, having too much provides negligible gains in my experience.

I really like @TA’s suggestion to “take the ISA’s current value and model how it falls if you halve the value of the equities and the bonds stay flat. If you can’t live with the result then go for a lower equity allocation.”

Applying this logic periodically (say, quarterly or yearly) through the accumulation phase seems like a fantastic way to decide how fast you should shift into defensive assets through time.

The only downside I can see is that the equities allocation that you can actually live with might not always provide sufficient growth over the very long term, especially for a very early FIRE-ee. But it’s better to confront a paradox like that than to live in denial!

Thanks for the 2nd installment and the barbell recommendation.

Please can I raise a couple of points?

You don’t seem to cover Property as an area to invest. The big pension schemes seem to have this as part of a low-risk strategy – LDI, hedging, bonds & commercial property. Owning a bit of a science park near Cambridge via a fund of funds might be a safe investment?

I read the various links, “How to invest in sectors, themes, and megatrends” etc., and get the logic for not doing thematic investing. But intuitively megatrend thematic investing seems to make sense. Russian equities, Hedge funds, Timber, Music royalties aren’t megatrends but more like risky bets. But ageing demographics, climate change, continual technological break throughs are. They will generate unmet needs – social care, healthcare, biotech, food security, non-carbon energy.

They mean in 10-20 years time the world will be different than today and new businesses will emerge in the roulette wheel of progress and market performance.

So for example it is probable there will be a Hydrogen economy in the next 10-20 years: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-government-launches-plan-for-a-world-leading-hydrogen-economy

Wouldn’t a diversified portfolio not want to add a bit of this to future-proof the risks of the investments not growing fast enough?

Could I ask some advice/opinions please.

I’m recently retired and want to follow the 60/40 method in retirement BUT do I include guaranteed pension income as part of our assets?

So, a state pension of £9,000 a year = a pot of £220,000 if we assume a drawdown of 4% and a final salary pension of £10,500 a year = a pot of £262,500 if we assume a 4% drawdown rate.

So, if my wife and myself have combined guaranteed pensions equivalent to £800,000 and savings of £100,000 (yes, I know a nice position to be in) do I add them together to £900,000, treat the guaranteed pensions as bonds and put our £100,000 savings 100% into equities? We are not big spenders and bizarrely our pension income is actually bigger than our working income over the last 5 years so in theory we do not need to take any risk with our savings to keep up our current lifestyle.

Hi,

With regard to zxspectrum48k comments on long govn bonds and cash have i understood that these would replace the suggestions you made below to leave equities, cash & long bonds/gilts (in50/50% split) or are linkers & gold still recommended? ie does zxspectrum suggestions only cover the intermediate bonds?

ie equity 60%, cash 15%, gilts 5%, linkers 10%, gold 10%

Equities for growth.

Index-linked bonds for inflation protection.

Cash for short-term needs.

An intermediate bond fund to cushion stock market falls.

60% Global equities (growth)

10% High-quality intermediate government bonds (recession resistant)

10% High-quality index-linked government bonds (inflation resistant)

10% Cash (liquidity and optionality)

10% Gold (extra diversification)

@ Robin – You’ll gain exposure to commercial property through a global index fund. Commercial Property performance is often characterised as lying somewhere between equities and bonds, hence it’s a diversifier.

I’ve read research that shows commercial property is highly correlated to equities in a downturn, however. Moreover, REIT trackers are highly correlated with the broader equity market. So I’m highly doubtful that tilting towards REITs provides much diversification value when we need it most – in a crash.

If you invest in a specific scheme such as a science park near Cambridge, you’re back to the active fund problem. Will that specific bet produce better risk-adjusted returns than a broad market index tracker after costs? How correlated is that asset to the broad market? Will it behave differently?

If you have an informational edge then it may be worth betting against the market. If not, then don’t.

Re: megatrends. You’re right, it isn’t in doubt that we will need more healthcare and clean energy in the future. But that doesn’t make for a successful investment. Everyone else has the same information. The market has determined the value of the companies operating in those areas today. Investing in a Clean Energy ETF will deliver outperformance if those companies are currently undervalued relative to future profits. But Clean Energy will underperform if investors have overpaid for those future profits today.

In the megatrends piece, the graph shows that investors in airlines consistently overvalued the potential of those firms. Everyone knew in the 1940s that this industry was going to be important in the future. But the succeeding decades proved it less profitable than predicted, despite its growth.

The internet in 2001, railways and canals are all famous examples of industries where investors got burned because they overestimated future profits. Much the same sentiment about the future helped fuel the speculation that led to the Wall St Crash.

Hydrogen will hopefully be a productive part of our economy for decades to come. But what matters is how much you’re paying now for a future slice of the action. Imagine you buy into hydrogen today. But tomorrow there’s a massive breakthrough in fusion energy. Hydrogen company share prices inevitably drop because its role in plugging renewable energy intermittency is diminished.

It’s a cartoonish example but hopefully helps illustrate that knowing that certain industries will likely grow in the future isn’t enough.

Bear in mind that you’ll have exposure to all the industries you mention in a global index tracker as those firms go public and gain in value.

A good reason to invest in particular sectors was supplied by ZXSpectrum48k. He invests in certain sectors as a hedge:

https://monevator.com/the-60-40-portfolio-problems/#comment-1373477

e.g. ZX tilted his portfolio towards the tech sector in case the onward march of tech eliminated his line of work.

@ Mark T – I think your situation depends on your income needs. If you need the £100K to generate essential income then 100% in equities risks draining your pot too quickly – if you hope your retirement will last a good few decades. The inherent volatility of equities means extreme return sequences can make you very rich but also very poor if you *have* to sell them.

OTH, if your equities cover discretionary spending then your final salary / state pension are wonderful inflation-linked bonds that cover your essential spending. In that case, you won’t be a forced seller and 100% equities is fine as long as it doesn’t cause you worry if it underperforms.

A floor and upside strategy may fit your situation better if the £100K covers discretionary spending:

https://monevator.com/the-most-important-goal-for-every-retiree/

https://monevator.com/secure-retirement-income/

If the £100K covers essential spending then a diversified portfolio helps you avoid nightmare scenarios where equities fail to deliver.

@ Lawrence – long bonds would replace intermediate bonds. You’d hold a smaller percentage in long bonds and more in cash to maintain the equivalent duration risk. The other assets still offer diversification potential e.g. long bonds are most likely to suffer in runaway inflation scenarios. But linkers are the best asset to guard against this risk. Gold has the potential to perform when other assets don’t, but no guarantees.

@Robin

I learned the hard way that property belongs in the risky side of your asset allocation. My L&G REIT tracker dropped more than 25% in a few days in March 2020.

The idea with index funds is that other market participants are equally aware of these trends and have allocated their capital with this knowledge. So the index weights already have these trends factored in.

I just made a small one off payment into my Vanguard Sipp and noticed that they are using numbers like the above in the illustration. They assume inflation of 2% and after this has been subtracted are using Lower: -0.3%, Medium: 2.7%, and Higher: 5.7%.

@TA – thanks for a great series…although it may mean I have to work longer to make up the shortfall against my plan! Time will tell…

I’m a bit confused regarding the bond holding. Am I right in thinking that my LS 60/40 is ok, but to also hold short duration index linked UK govt gilts that will show little or no return but will not fall in a market correction and provide backup whilst equities recover?

Also, I’m thinking of increasing my portfolio with a 16% tranche of Short Duration Global Index Linked bonds hedged GBP (Royal London) to balance up the 68% of my current equity holding which is there to offset inflation.

In my eighties, I realise that the equities can drop and not recover until after the GR has beckoned, but everything is a gamble and I’m pleased to have reached this far.

My current portfolio is outlined below. Any suggestions and information would be appreciated.

18% Eqty active (Fundsmith & SMT)

50% Eqty index (LS60/40)

23% Bond index (LS 60/40)

5% Bond active

1% Gilt index

3%. Cash.

@TA Thanks for the feedback. Yes, I agree with the thoughts. The internet was a megatrend with a huge great bubble that blew-up in 2000. I remember it well. Market crashes are not fun, 2008 was quite something. Japan has never regained the high of 1989. The 2020 crash wasn’t too bad in the end.

My approach has been to build diversity. I’ve done this through a range of active/passive funds across asset classes – bonds, multi-asset, commodities, property, equity etc…. in general global but some geographic. It seemed like a good idea.

The recommendation to significantly concentrate on passive over active could well be right. Would reduce ongoing costs. Plus simplify things. Are there risks in going passive? Either way, thanks for the thoughts, I’ll do some more research.

@Jon, yes, I bought the property fund when Covid was at it’s height. I thought it was one of those “buy when everyone is selling” moments. It’s done OK, but agree would probably crash with the next market crash.

@The Accumulator

Thanks very much for the advice, I’ll have a read of the links and have a good think. At this stage I’m leaning towards the 60/40 as being a set it and leave it solution. My wife is not interested in investing so I’ll have to ensure our situation is straightforward if I die first.

@ Barney – index linked bonds are the best defence against spiralling inflation scenarios. Think stagflation. Note equities don’t perform well in these circumstances.

Conventional gilts are most likely to help in standard recessions when equities take a beating. They counter-weight corrections much of the time but not always.

The following two pieces show how conventional gilts and index-linked bonds performed in the last two big crashes:

https://monevator.com/how-diversification-worked-during-the-global-financial-crisis/

https://monevator.com/diversification-in-the-coronavirus-crisis/

The behaviour shown in these two snapshots demonstrates what you’d expect to happen. However, there are no guarantees that asset classes will always follow the script.

This piece walks through UK asset class history to illustrate that point. It shows that a blend of asset classes works:

https://monevator.com/how-to-protect-your-portfolio-in-a-crisis/

These two pieces hopefully help explain how the role of the various bond types in your portfolio:

https://monevator.com/bond-asset-classes/

https://monevator.com/defensive-asset-allocation/

@ Robin – a passive strategy doesn’t expose you to any new investing risk relative to an active strategy. Except for one: you give up the hope of trying to beat the market because the evidence shows the attempt is likely to leave you worse off after costs.

The only other risk I can think of is psychological. Billions in assets have shifted from active to passive funds over the last 15 years as investors accepted the evidence.

The response of the active fund industry has been to invent new ways of marketing the possibility of beating the market. And to launch high-cost products disguised as trackers.

It seems to me that a lot of people find that promise hard to resist. I think that some people who broadly accept the evidence in favour of passive strategies hedge their bets by taking some active exposure too.

@ Mark T – You make a very important point: simplicity can be invaluable in situations we’d rather not think about e.g. when we leave loved ones behind or in the face of cognitive decline.

@TA, thank you for that info which I’m going through now.

I was uncertain because “Covid” caused my portfolio to dip just **12.5%, (thanks to the passive portion) including 4/5-star active corporate bonds which dipped 40%, whilst my Vanguard UK gilt increased 14+% but is now showing a small loss after I switched the profits.

Because the UK corporate bonds recovered after the active funds, I switched them into FTSE All-World UCITS ETF VWRL.

I want to retain the active portfolio portion, Fundsmith and SMT, and will rebalance my portfolio with a cash injection into UK index linked Gilts and Short Duration Global Index Linked bonds.

Not as advice, but is there anything in doing that rebalance now or would it be prudent to wait.

** During 2007/9 my active portfolio dipped 49.5% taking 2 years to recover.

@ Barney – there’s no reason to wait. You’re making a strategic shift which will hopefully give you more options in the face of uncertainty so it makes sense to push on.

@ TA, got it, thanks.

@TA do you have any thoughts on how to hold what could be a significant amount of cash please? Simply as uninvested funds within a SIPP/ISA, in cash ISAs, or are there any specific funds/ETFs which are extremely low risk?