A lot of people confuse tax avoidance and tax evasion. It can be a dangerous mistake to make.

As the former British Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey once said:

“The difference between tax avoidance and tax evasion is the thickness of a prison wall”.

That was why in the original published version of this article I stated:

- Tax avoidance means using whatever legal means you choose to reduce your current or future tax liabilities.

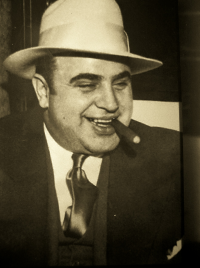

- Tax evasion means doing illegal things to avoid paying taxes. It’s the Al Capone path to financial freedom.

However the authorities have taken an increasingly tough line in recent years.

Now the phrase ‘tax avoidance’ may imply something much more questionable, as opposed to simply filling an ISA.

Tax avoidance might not be legal. Depending.

In particular, a General Anti-Abuse Rule (GAAR) was contained within the Finance Act 2013. This sought to counter ‘tax advantages arising from tax arrangements that are abusive’.

You should definitely delve into detailed guidance on GAAR if you’re contemplating doing anything out of the ordinary.

But the most relevant point for our discussion of evasion versus avoidance is that according to the tax planning resource RossMartin.co.uk:

In addition to the legislation, HMRC published guidance in April 2013 which expressly states that the GAAR is an intended departure from the previous situation where routinely cited court decisions such as the judgment of Lord Clyde, ‘every man is entitled if he can to order his affairs so that the tax attracted under the appropriate act is less than it otherwise would be’ are now rejected.

The guidance sets out the Parliamentary intention that the statutory limit on reducing tax liabilities is reached when arrangements are put in place which go ‘beyond anything which could reasonably be regarded as a reasonable course of action’.

And here’s what the Tax Justice Network says about the difference between avoidance and evasion:

Tax avoidance cannot be called ‘legal’ because a lot of what gets called ‘tax avoidance’ falls in a legal grey area. ‘Tax avoidance’ is often incorrectly assumed to refer to ‘legal’ means of underpaying tax (such as using loopholes), while ‘tax evasion’ is understood to refer to illegal means.

In the real world, however, this legal-illegal distinction often falls apart.

Whether an activity is legal or not often does not become clear until it has been challenged in court, and much of what gets called ‘avoidance’ turns out to be more like evasion.

As a result the Tax Justice Network – a lobbying group that focusses on states’ getting their due share of tax receipts – now favours the phrase ‘tax abuse’.

Tax avoidance may not be a criminal act then – depending. But if you’re hit with a big bill and penalties because what you did was deemed by a court to be the unacceptable face of paying less tax – ‘unreasonable’, in other words – then you may wonder if there’s a difference.

Please note I am NOT a tax expert and this article is not tax advice. It is simply the musings of a private investor trying to do the right thing with my own affairs. Consult a specialist and/or HMRC to know exactly where the law and you stand in respect to your taxes.

Tax avoidance out. Tax mitigation in.

For any criminals who Googled ‘tax evasion’, I’m not about to give you a masterclass in laundering cash or doctoring a passport.

I’ve never evaded taxes. I don’t condone it, and I couldn’t tell you how it’s done.

But tax avoidance mitigation – as we should now call it – is another matter.

The previous version of this piece already predicted taxes would rise in the UK over the next few decades. Higher pension costs, public debt, and the ever-rising bill for funding public services made that nailed-on.

Since then though we’ve seen public sector borrowing soar due to the pandemic, pulling forward this pressure. The overall level of taxes is now forecast to hit the highest level since the Second World War:

Our stagnant post-Brexit economy means it’s unlikely faster economic growth will bail us out anytime soon. Living standards will remain moribund, regardless of what party in power.

Meanwhile politicians increasingly talk about closing tax loopholes. In some cases – such as the carried interest enjoyed by private equity that’s now in the crosshairs of shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves – these are not improper, just disagreeable to a State with an insatiable appetite for more revenue.

Against this backdrop, it makes sense for investors to legally do what we reasonably can to reduce our tax burden – without overly compromising on other aspects of our lives, I’d suggest. (As opposed to be following the example of 1970s tax exiles…)

In doing so, we need to be extra careful today to follow the spirit as well as the letter of the law.

Examples of legitimate tax mitigation steps

There’s plenty you can do to reduce your taxes without risking fines or jail time.

ISAs and pensions

Most people can do all their investing entirely within tax shelters such as ISAs and SIPPs. They will not have to worry about further tax mitigation with respect to their investment returns.

VCTs and EIS schemes

These are riskier and (worse) more expensive ways to invest. But they can have a role for wealthy investors who’ve filled their tax shelters and can afford to chance lousy returns. Especially if they particularly enjoy backing new companies.

Think about who owns your assets

If you’re a married high-earner, it may make sense for your lower-earning and more lightly-taxed spouse to own certain assets and book the returns. Make the best of your family’s various personal allowances, but maybe take advice if you feel you’re contemplating anything unusual.

Consider salary sacrifice and other steps to lower income tax

The aim is to defer paying taxes until you’re earning less in retirement, and thus will be taxed at a lower rate.

Taxing taxes

I’m confident those tax mitigation methods are fully within the spirit of the law. That’s because when you invest in an ISA, say, you are doing exactly what the legislation intended – enjoying a tax break given as an incentive to invest for your future wealth.

But once you – or your advisors – start to get creative, you roll the dice.

When I first wrote about tax avoidance versus tax evasion in 2009, it seemed like a less contentious subject.

Of course, nobody liked a tax evader, then or now.

But over the past decade or so – perhaps spurred by the popular backlash that followed the financial crisis, and boosted by the cost of living crisis more recently – politicians, the media, and the public have cast a harsher eye on even seemingly legitimate tax avoidance, too.

This has made the distinction between evasion and avoidance blurrier than it was.

Yet this is not really a new issue. Writing in the Financial Times in the wake of a controversial craze for tax inversions by US companies, John Kay noted:

It is conventional to distinguish legal tax avoidance from illegal tax evasion. But the reality is that there is a spectrum.

The person who avoids the heavy taxation on cigarettes by giving them up wins our approval; the gangmaster who employs illegal workers off the radar screen of government authorities goes to prison when detected. But most cases lie in-between.

The UK’s HM Revenue & Customs has issued big payments claims to people who invested in highly artificial film finance schemes that did not qualify for the allowances they claimed.

Were they avoiders or evaders? The line between avoidance and evasion would be clear only if the law were clear, and it is not.

Tax law is complex and the legality of particular actions can be firmly established only if there is a decision by a court on the facts of a particular case.

A tax avoidance horror story

The fate of the film financing schemes in the courts since Kay wrote his piece has had as many plot twists as any movie. Like most people not directly involved, I lost track.

I do know though that a Supreme Court ruling in 2017 ultimately found for HMRC – potentially recouping £1 billion for the nation’s coffers, albeit at potential ruin for users of the schemes. Some of them reportedly faced tax bills several times larger than their original investment.

An HMRC spokesperson was quoted as saying:

Avoidance schemes are often highly contrived and almost invariably fall flat when trying to deliver a tax advantage never intended by Parliament.

The fact is the majority of schemes simply don’t work and can put avoidance users in a significantly worse financial position than if they had never used the scheme in the first place.

Even MPs got involved in the drama, pushing back against court rulings – or at least on the penalties imposed.

In a letter to then-chancellor Philip Hammond, Andrew Tyrie, chairman of the Treasury committee, agreed the original film industry tax breaks were arguably “too generous and ill-defined.”

But with respect to rulings against the schemes designed to exploit those breaks, Tyrie added:

An increasing number of representations have been made to me expressing concern that the outcomes are not always fair nor what anyone could have expected.

This has resulted in financial calamity for some of those involved and considerable difficulties for HMRC in bringing a large number of schemes to a close.

The affair was still rumbling through the courts as late as May 2023.

Better know better

These film financing vehicles were marketed some 20 years ago. But the saga illustrates very well that what may seem a clever wheeze one moment can levy a heavy price in time.

Most Monevator readers will have little sympathy with multi-millionaire celebrities apparently going out of their way to avoid paying more taxes to fund schools and hospitals and the rest of the laundry list.

And I am certainly not saying the film schemes were legitimate. The courts have found they were not.

However there’s a bit of going somewhere but for the grace of God about it all.

Those celebrity investors were presumably mostly advised by specialists. I suppose that many just assumed the schemes were above-board.

After all, it took a very long-running court case to prove they weren’t. How was a footballer or a pop star supposed to be able to assess that, when presented with the scheme by a professional person in a suit?

Compensating factors

Consider, by way of comparison, the Payment Protection Insurance mis-selling scandal. By the end the banks had paid out nearly £40 billion in compensation to customers deemed to have been mis-sold PPI.

For these PPI ‘victims’, caveat emptor did not apply. They eventually got their money back.

But for the would-be tax-avoiding film financiers, caveat emptor has bitten them on the bottom line.

How would we feel, if formerly commonplace practices such as pension recycling or bed and ISA-ing were suddenly deemed too aggressive?

And we were then hit with a retrospective tax bill?

Exactly.

I’m just thinking aloud. Again, I’m far from an expert on tax matters. We never give personal advice on Monevator, for both practical and regulatory reasons. But I’m always extra wary when it comes to tax.

The fact is that tax matters are often very complicated. And often dependent on your personal situation.

The letter of the law

Interestingly, in the original version of this article posted in 2009, I quoted evidence of an emerging debate about the terminology as then covered on Wikipedia.

At the time the phrase ‘tax avoidance’ was apparently in dispute in the UK, with ‘tax mitigation’ being suggested as a better term for legal tax reduction.

The Wikipedia article noted, in paragraphs since removed, that:

The United Kingdom and jurisdictions following the UK approach (such as New Zealand) have recently adopted the evasion/avoidance terminology as used in the United States: evasion is a criminal attempt to avoid paying tax owed while avoidance is an attempt to use the law to reduce taxes owed.

There is, however, a further distinction drawn between tax avoidance and tax mitigation.

Tax avoidance is a course of action designed to conflict with or defeat the evident intention of Parliament.

Tax mitigation is conduct which reduces tax liabilities without “tax avoidance” (not contrary to the intention of Parliament), for instance, by gifts to charity or investments in certain assets which qualify for tax relief. This is important for tax provisions which apply in cases of “avoidance”: they are held not to apply in cases of mitigation.

I wrote at the time that: “I suspect this is largely a courtroom debate, caused by the Revenue looking to close down schemes of dubious legality created by planners for wealthy individuals.”

And indeed, that does seem to have been the direction of travel in this area, given that later ruling in the 2013 Finance Act.

Avoid being deemed an overt avoider

So where does this leave us?

As I say I’m no legal expert nor a tax planner. I’m just an everyday bloke who enjoys investing.

So to be absolutely clear, whenever I’m talking about reducing taxes on your investments, I mean by using legal and strictly above board means. Never the dodgy stuff.

But perhaps this isn’t enough anymore? Maybe we should apply the ‘seen on the front of the local newspaper’ test to any decisions we make when reducing our taxes?

In other words, how would you feel if whatever tax mitigation decision you made was splashed on the cover of your local newspaper? For all your friends and neighbours to read?

Saving into a pension? Putting money in an ISA? Making use of capital losses by setting them against capital gains to reduce your total taxable gain?

All very safe.

What about defusing capital gains over the years by making sure you use your capital gains allowance? Or incorporating your business to reduce your income tax bill and national insurance liabilities?

Already in the current climate we can see they seem a bit less safe. I think though they are still firmly on the right side of the spirit and reality of the law, if not always the court of public opinion.

What about offshore vehicles? Or using complicated company structures or loans to avoid payroll taxes or to disguise renumeration?

Hmm. I wouldn’t and HMRC would agree.

And as barrister Patrick Cannon notes on his website:

…if HMRC investigate and find evidence of dishonesty or cheating then you may be looking at a criminal investigation for tax fraud and prosecution, leading to a prison sentence and a fine.

The sort of behaviour that this might cover includes claiming that genuine loans were made as part of the scheme when they were not genuine; or the writing of fake work diaries showing the taxpayer having spent time in the business when they were elsewhere. In my experience, these fake diaries are often produced by the scheme promoters and sent to the users for signature.

Avoid getting involved in anything dodgy or complicated like the plague. Jail sucks.

In fact, I personally draw the line at the vanilla tax mitigation I mentioned above. Beyond those straightforward measures, pay up and be happy you have the means to do so.

How to spot avoidance in action

In any event, it seems ‘avoidance’ has become a dirty word – at least when applied to contrived arrangements designed simply to reduce your tax bill.

More official advice from HMRC:

How to identify tax avoidance schemes

Here are some of the warning signs that you might be in a tax avoidance scheme or you are being offered to join one.

It sounds too good to be true

It almost certainly is. Some schemes promise to lower your tax bill for little or no real cost, and suggest you do not have to do much more than pay the scheme promoter their fees and sign some papers.

Some schemes designed for contractors, agency workers and other temporary workers or small and medium sized employers, involve giving workers some or all of their payment either as a loan or other payment that they’re not expected to pay back.

The payment may be diverted through a chain of companies, trusts or partnerships often based offshore and received from a third party. Sometimes the payment is received directly from an employer.

Other ways in which these untaxed payments may be described include:

- grants

- salary advances

- capital payments

- credit facilities

- annuities

- shares and bonuses

- fiduciary receipts

In all cases the schemes promise to put money in a workers pocket without having to pay tax on it. These schemes are often sold by non-compliant umbrella companies.

Huge benefits

The benefits of the scheme seem out of proportion to the money being generated or the cost of the scheme to you. The scheme promoter will claim there’s very little risk to your investment.

Round in circles or artificial arrangements

The scheme involves money going around in a circle back to where it started, or some similar artificial arrangement where transactions are entered into which have no apparent commercial purpose.

Misleading claims

The scheme is advertised using misleading claims. These may include claims suggesting a scheme is endorsed or approved by HMRC or that a scheme can increase your take home pay. For example:

- ‘HMRC approved’

- ‘Retain more of your earnings after tax’

- ‘We ensure you get the highest take home pay’

- ‘Compliant tax efficient pay’

These statements are likely to be misleading. HMRC does not approve tax avoidance schemes.

HMRC has given it a scheme reference number (SRN)

If HMRC has identified an arrangement as having the hallmarks of tax avoidance and are investigating it, you will receive an SRN by your promoter and you should include this on your tax return.

If an arrangement has an SRN, this does not mean that HMRC has ‘approved’ the scheme. HMRC does not approve any tax avoidance schemes.

If an arrangement does not have an SRN, this does not mean that the arrangement is not tax avoidance and could still be investigated.

Non-compliant umbrella companies

Many umbrella companies operate within the tax rules, however, some umbrella companies promote tax avoidance schemes. These schemes claim to be a ‘legitimate’ or a ‘tax efficient’ way of keeping more of your income by reducing tax liability.

Find out what to do if an umbrella company offers to reduce your tax liability and increase your take home pay in Spotlight 45.

Schemes HMRC has concerns about

You can find examples of tax avoidance schemes HMRC is looking at closely. Even if a scheme is not mentioned, it may still be challenged by HMRC.

You might also find HMRC’s report on the use of marketed tax avoidance schemes worth reading if you have reason to want to know more.

If in doubt, pay the tax

Well, there you have it. I know I haven’t done anything dodgy – my affairs are far too boring, and after years of defusing capital gains, nearly all my investments are these days in tax shelters or else qualify for EIS exemption.

I hope you haven’t strayed either. But the woeful fate of the film financing schemes shows how even wealthy and professionally advised investors need to be careful and remain vigilant.

Thoughts and corrections welcome in the comments, especially from experts.

Let’s be careful out there.