I tend to ignore most of the doom and gloom you read on the Internet.

Peak oil? Piffle.

China crisis? Chortle.

The only catastrophic fear that reliably gets me going is environmental degradation, because there are so many ways for us to screw up.

We could avoid planetary collapse, say, but still see the Earth turned into a giant pig farm. Perhaps the planet will ‘support’ 10 billion human beings, but only a few hundred thousand wild animals.

That would be failure to me – but our descendants might watch old David Attenborough TV clips while eating Quorn burgers and think life is not so bad.

Capitalism: endangered

In recent years however I’ve been vexed by another popular apocalyptic grievance.

That’s the so-called crisis in capitalism.

Just like the daily damage we’re doing to the environment, it’s hard to deny Western economies have taken a turn for the worst.

And what makes this brew especially potent is that not everyone is suffering equally.

Given how the wealth of the richest has risen ever higher above the rest of us in the past two decades – and how we now seem to lurch from one systemic crisis to another, which I suspect is related – I wonder what capitalists from the 1950s and ’60s would think, could they see us today?

Would they reach the same gloomy verdict as a biologist might on visiting a pitiful 5,000-acre ‘Real Amazon Rainforest Experience’ in Brazil come the 22nd Century?

Would they find capitalism just a shadow of its former self?

Free markets rule, okay?

The reason I’m not worried about most of the ‘big’ problems is because I think human beings are ingenious creatures who haven’t begun to fully harness the resources around us.

This is why I am also a capitalist, despite its recent traumas.

I believe that free markets with transparent pricing, private property rights, and the profit motive of ambitious individuals are together pretty good at allocating resources and eventually solving problems.

This doesn’t mean I think we should give into winner-takes-all ideologies, or that all taxation and redistribution is wrong. Capitalism without checks and balances is feudalism with price tags.

But I do believe the evidence is capitalism is more effective at improving the lives of more people than the alternatives.

And yes, I believe it’s better for me, too.

I also think well-functioning capitalist societies are freer societies – because they need to be to work. Not perfect by any means, but demonstrably fairer and freer than the Soviet and Chinese experiments in communism were.

Some on the left dismiss those repressive regimes as hijacked by dictators. But I suspect the low value put on an individual freedoms in those economic regimes was no accident, given their over-arching credo.

Coffee chain socialists

Given my beliefs, then, I’m dismayed to hear well-educated friends increasingly writing off capitalism as broken and corrupt.

In my view, most of our progress in the past few hundred years was facilitated by free markets – and capitalism is the only hope I see for tackling the big problems of the future.

I listen in disbelief as intelligent friends report back from a community farm in Hackney to tell me that one day all our food will be grown on shared allotments in Acton and Ealing. What did they smoke there?

Another friend regularly lambasts the post-War medical system, saying it’s “never done anything for patients, just profits for companies”, ignoring the multiple successes against everything from heart disease to AIDS, and the enormous R&D advances in Europe and the US (research which incidentally the rest of the world, including the poorest, effectively gets a big subsidy on).

Other frightening things overheard at recent dinner parties:

- “Western economies are the reason people are starving in this world.”

- “You’re delusional if you believe money has any real value anymore.”

- “Who cares about greedy shareholders?”

- “You should be ashamed of yourself for reading the FT“.

These comments might have been standard fair in a 1970’s university common room for students still a few years away from having to test their principles in the real world.

But that they are being made by intelligent grown-ups with houses, pensions, jobs, and holiday plans to far-flung locales – everything that capitalism can buy – is to me deeply worrying.

These friends of mine see no connection between their everyday well-being and the economic system that supports them. It’s as if the demise of communism has left them free not to believe in capitalism, but to indulge in dangerous fairy tales.

And their complaints are getting louder. I’d say the majority of my University-educated liberal friends will ‘Like’ anything on Facebook that includes a rant about the evils of the market system or of trying to balance the nation’s books.

Sometimes I wonder if I’m living in a Truman Show designed to rile me. Perhaps these friends really do spend their days sabotaging the best efforts of their capitalistic employers, and maybe their conspicuous consumption is some sort of ironic political statement.

Or perhaps they’ve just been infantilised into hypocritical posturing.

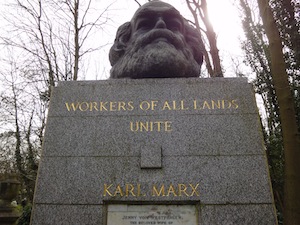

The new Marx brothers

How have we got to this miserable state of affairs, where smart individuals raised and doing well in capitalist societies are apparently calling for its downfall?

Do my friends have some great solidarity and empathy with, say, the vast swathe of young Spanish people jobless in the wake of the financial crisis?

I don’t think so. Besides, if you want to find real injustice in the world you need to go a lot further than Spain, which is the architect of much of its own misfortune.

A lot of the world’s population never had the luxury of a functioning capitalist economy to screw up. Many Africans and Indians live in near post-apocalyptic conditions, for example – exactly the sort of dire scenario painted by comfortable Westerners who cheerfully muse about imminent economic collapse and growing their own carrots in a bucket.

Clearly it is partly a knee-jerk reaction to the last few years of economic tumult. I think people are also looking to the endlessly infuriating bankers, the Flash crash in the stock market, riots in Greece and Italy and even the UK, and are scared by a system that has at times seemed out of control (as it always was, of course. Which is, incidentally, why it works).

But I think the most important factor for my friends’ incoherent ranting is that in the post-Soviet era, a well-articulated counter to rampant capitalism has been conspicuously absent. The sort of crisis predicted by communists has come and gone, but there are no communists left to – ahem – capitalise on it.

The centre cannot hold

Without the checks that the fear of ‘the Reds’ put on Western capitalism, unions have collapsed, left-wing politics has morphed from productive redistribution to doling out windfall taxes to buy votes, and a centrist politician in the US like President Obama is derided as a ‘socialist’.

Few young people seem to know much about economics and politics anymore. You might say I’m an old (30-something) fogey ranting, but the benefit of growing up with Thatcher versus Kinnock and Reagan versus Soviet Russia was that almost everyone took some sort of political stand, prompted by real conflict.

Today, my friends happily claim “the Tory’s have slashed NHS funding and are sacking 50,000 doctors and nurses”, when the tedious reality is real terms NHS spending fell by 0.02% (by accident) and Labour would have had to take the axe to spending, too. The distinction between the UK parties is more rhetoric and rounding errors than real policy differences, yet the charges of “wrecking the NHS” or “bankrupting the nation” from either side remain as loud as ever.

The trouble with this phoney debate is that nature abhors a vacuum, and my well-educated middle-class chums effectively calling for some sort of Mad Max collectivism – with hot showers and foreign holidays – demonstrate it’s not just in Greece that people will believe almost any nonsense in the face of tough decisions.

Meanwhile, back in the boardroom…

In the absence of alternatives, like a bell, today’s Western discontents have nothing to hit out against except themselves.

The irony is that there is a political spectrum worth debating, but it’s been crowded out by right-wing ranting in the US and left-wing, well, lying, here in the UK. Rather than invigorating politics, these radicals render it impotent, stretching the fringes even as the centre becomes crowded with focus groups, working parties, and career politicians.

The lack of proper political debate – and I’d count the mainstream media as part of the problem – means the average person today seems to have no idea that you can have more ‘humane’ versions of capitalism, such as that historically practiced in Scandinavia, or the cultural traditions in places like Germany and Japan where bosses are rewarded far more handsomely than their workers – except it’s arithmetically more (10-20 times as much, say) rather than geometrically more like in the US (200-400 times more) and increasingly in the UK.

That alone is one massive choice about what sort of system we want to live in – and yet it stops far short of deriding profit as evil, or similar counter-productive dinner party nonsense.

Indeed, perhaps it’s the most important choice: I think the growing chasm between the very richest and everyone else is a big part of what ails Anglo-Saxon capitalism.

Income inequality is getting more extreme, with the US leading the way as this graph from The Economist reveals:

The rise of the infamous 1%

Anecdotal asides are even more shocking.

An article entitled America’s dream unravels in the FT reveals:

[Among America’s hyper-rich] there are the retail kings, such as the Walton family, owners of Walmart, whose combined assets equal that of America’s bottom 150 million people.

When I read statistics like that, I’m not quite so surprised that I’m regularly defending capitalism in the pub, or that half my conversations now involve persuading old friends I’m not a robber baron for buying shares.

My friends aren’t on the lunatic fringe. They are (mainly) serious people with proper, well-paid jobs, who have come to believe the entire financial system is a rigged game run for the benefit of insiders, and I think the distortions at the top of the income and wealth scale are a big part of the reason why.

Will capitalism eat itself?

Much of this post has been sitting in my draft folder for a year. I’m not happy with it even now; I feel inarticulate. I am sure something big is happening, and that people’s lack of faith in the economic system is more dangerous than just sour grapes in a downturn, but I struggle to say why.

Meanwhile, in the time I’ve been avoiding writing about it (as hinted at in my post-Libor scandal banker post) the Occupy / 99% movements have bubbled up and income inequality has moved to the mainstream.

Yet even now, business people and private investors – the very people who should be figuring out what’s gone wrong and selling the benefits of what’s more often gone right with our system – seldom seem to have anything to add. They leave the airwaves to the extremists.

As I discovered in my banker bashing days, if ordinarily successful private investors comment at all, it tends to be to stand up for the grossly-inflated salaries of the ultra-rich elite, the bankers and the directors of big companies – an income skew that I think may eventually be too much for our system to bear.

True, we’ve had the so-called Shareholder Spring. But as the BBC’s Robert Peston recently wrote, it’s a myth that this has restrained executive pay:

The disclosure that FTSE100 chief executives were last year awarded average total remuneration of £4.8m, a rise of 12%, will be seen by many as shocking.

It comes at a time when earnings for the vast majority of people are stagnating and represents a record of just over 200 times average total pay in the private sector of just under £24,000 (on latest figures from the Office for National Statistics).

[…]

[Yet] there have been just four defeats so far of companies in votes on their so-called “remuneration reports”, and only one of these companies has been in the FTSE100 list of biggest businesses. That does not represent an exponential increase in shareholder rebellions.

Personally, I think a world where top CEOs earned say 30- to 50-times the average income is still plenty aspirational. In fact it’s the 1950s and ’60s – what many would regard as the golden era of Western capitalism.

Suggest it though, and you’ll hear you’re a communist who wants to reward people for sleeping in bed and to punish the successful.

Investors of the world, unite!

There could scarcely be a more important topic than the growing distortions that threaten capitalism, but whenever I discuss it with my financially-savvy friends they lecture me about football stars and Simon Cowell.

I suppose it’s like the omertà code of the mafia: The fear is that if you engage with the argument at all, it will lead to some re-energised union leader or lefty politician taking your own toys away. (I also suspect people think they themselves are knocking on the door of the rich club, when most are not.)

Yet to say nothing is to let the hysteria grow.

If for no other reason, debate it for naked self-interest! Western economies cannot grow without consumers, and polarising inequality means ever more money is compounding at the top. There’s only so many private jets and country mansions the super-rich can buy.

I also think there’s a strong argument that it was stagnant wage growth for the masses in the US that set the scene for its borrowing binge and sub-prime mortgage bubble. People attempted to keep up with the aspirations of their parents, but without the growing pay packets to do it.

Now I don’t deny there are structural issues at play, too, such as globalisation (which I favour) and growing network effects.

But whatever the ultimate answer, I believe it’s a responsibility of all of us who support free markets – let alone those of us who hope to profit from them via investing – to stand up and be counted, and to be sure we can justify any aspect of the system that we defend, rather than indulging in fantasy politics of any persuasion.

I hope we do not come to regret not doing more to defend capitalism – including from itself.