I admit it: I’m a capitalist. I believe in free markets. I think the invisible hand can do more than pick pockets and grope hard-pressed students packed onto the privatised railways.

Greed can be good – if it makes companies more efficient and brings more of us the products and services we want at lower prices.

Outrageous? Before you lynch me, you’d better know I’m not the only one.

We capitalists aren’t horned beasts dancing around pyres of sub-prime mortgage certificates. We’re men and women of all shapes, races, and ages. We have places where we get together, where we whisper to each other interesting business opportunities and swap tips on investing our SIPPs.

But these days we’re scared to be out and proud.

What a shame! We live in a capitalist world, and it’s only by living as capitalists that we can truly make the best of it. Capitalism isn’t just for golf club swingers and septuagenarians in South Kensington. It’s the system we all work within.

Unless you’re a dropout living in a tree tent above an anti-fracking campsite, you need to know the rules of the game to thrive. Taking a half-hearted approach to capitalism is like a goldfish taking a half-hearted approach to swimming.

You have to be in it to win it.

This is especially true as one of the least cuddly aspects of capitalism is it helps best those who help themselves.

The quickest way for the 1% to become the 0.1% is for the rest of us not to play the game.

With that in mind, here are 11 tips on how to be a capitalist.

1. Get some capital

Clues in the name. To be a capitalist you need capital. You can then invest this money to make more money, and be on your way to mega-riches. (Dust down your old Monopoly board if you’ve forgotten how it works).

I think one of the great strengths of capitalism is that it’s theoretically open to anyone. Rival systems claim to be more fair, but invariably they boil down to who you know (Marxism), who your parents were (feudalism), or who you were prepared to shoot in the head (dictator-ship-ism).

Most human beings will try to get ahead. Capitalism harnesses this, rather than fancifully suppressing it only to see it come out in less useful forms.

So, how do you get your capital?

Obviously it helps to be born to a rich capitalist . But most of us will need to spend less than we earn.

That difference is your seed corn. Saved and invested, it will be the start of your capitalist empire.

2. Own the means of production

Here’s what Karl Marx knew and you should, too:

“In capitalist countries, the rulers own the means of production and employ workers. Means of production are what it takes to produce goods.

Raw materials, machinery, ships, and factories are examples.

“Workers own nothing but their ability to sell their labor for a wage.”

If you want to thrive in a capitalist economy, you need to follow Uncle Karl’s advice and get yourself some factories, machinery and ships. Or rather their modern equivalents, like data centres, luxury retailers, and offshore oil drillers.

If you don’t own the means of production, then all you’re doing is selling your labour for a wage.

That is, you’re a wage slave.

Happily capitalism has come a long way since Marx’s time and it’s now easier than ever to get your share of the money-minting machines.

By putting your money into a stock market tracker fund, you’ll buy a slice of all the major listed companies in the country – or even the world, depending on which fund you buy.

These tracker funds are cheap to own, and enable you to leave your company managers to get on with making profits. As they do so, the companies will become more valuable, and the value of your holdings will rise.

By reinvesting the profits they pay out as dividends, you can buy more slices of the companies, too. Over time it’s reasonable to expect 5-8% growth a year in today’s money terms from your basket of global companies.

3. Own other assets, too

Owning a slice of the productive economy is key to getting your stake in the capitalist system, but companies are not the only assets to amass.

Other potential things to buy are rental properties, fixed income investments like bonds (where you’re basically making a loan to a company), and of course you want to keep some cash handy for future corporate raiding (a.k.a. buying into the stock market when it’s cheap).

You might even consider making loans to spendthrift wage slaves via Zopa, which now has a Safeguard in place that should protect you from bad debts.

The key is to have more income producing assets than money-sucking liabilities.

Some argue that our economy sneakily tries to turn even high-earners into indebted consumers. That way they stay on the treadmill of working and spending, enabling those at the top to stay rich.

I won’t get into the conspiracy theories here. But whether that theory is right or wrong, by refusing to play the consumption game and choosing to own assets instead, you’re closer to the top of the pile than the bottom.

4. Treat yourself as a company

Who is the archetypal capitalist – Bill Gates or Richard Branson?

For me Branson wins that matchup every time.

Gates may be richer, and with Microsoft he built a far bigger and more world-altering business than Branson ever did.

But Sir Richard is the consummate entrepreneur. He’s restless and forever shuffling his cards, always looking for how to best spend the next year and the next dollar to greatest effect.

Branson understood early the power of personal branding, especially in a nation of shrinking violets. And on a personal level, he doesn’t get hung up on what he can’t do (he’s dyslexic, for example) but rather on what he can.

Virgin is Branson, and his business activities are an extension of his ambition and of his curiosity about the world. It’s as far from the wage slave mentality as you can imagine.

Like Branson, you can treat yourself as a company, too.

What are your strengths? Where can you deploy your talents to earn the highest return? What assets are you not using, and where are you wasting money? Did you over-invest in a university education and under-invest in networking? Did you skip classes in the school of hard knocks?

What does your personal profit and loss statement and your balance sheet look like?

Not everyone needs to start a business or turn into an entrepreneur.

But to thrive in a capitalist world, it pays to sometimes think like one.

5. Turn yourself into a company

That said, it’s actually not a bad idea to become a company if you can.

I don’t mean you need to give up being a doctor or a programmer or whatever you are, in order to launch a rival to McDonalds.

But if you can you do your job as an independent, one-man band – a freelancer or consultant or small business owner – then there are plenty of advantages:

- With a diversity of clients (at least two!) you’re less exposed to the cost cutting measures of your capitalistic taskmasters. (i.e. Getting fired.)

- You’re usually taxed more attractively.

- It’s easier to put large amounts of money into a personal pension.

- If you invent something, you’ve a better chance of owning and exploiting it.

There are some disadvantages, of course.

When you run the show you can’t slack off, and the freelance and consultant budget can be the first to get chopped in hard times. Put money aside in case.

There’s also more paperwork, and you may need an accountant.

In many countries you’ll need to budget for healthcare, too, although in the UK we have the NHS to show for our taxes – a boon that’s often underestimated by UK entrepreneurs.

The next step beyond being a one-person show – running a proper, expanding business – is obviously gold stars and top marks when it comes to being a capitalist. Instead of making someone else rich, you have people making you rich.

Marx would say you’ve turned the tables. Now it’s you exploiting labour for your own profit – which is a result for our purposes.

Besides, there’s nothing to stop you implementing profit sharing or other enlightened benefits should you want to be a conscious capitalist.

It’s hard to start a business – much harder than some pundits with books to sell will tell you – and it’s risky.

I think becoming a self-employed problem solver is a good halfway house.

6. Create multiple income streams

Another baby step towards being the J. D. Rockefeller of your neighbourhood is to look for ways to add to your primary income.

Can you teach a musical instrument or a language, or some other skill? Could you invest in a franchise alongside an ambitious niece or nephew? Do you have expertise that would enable you to trade antiques for a profit? Could you write and publish your own digital books?

The list is very long, and your hours will be longer than Joe 9-5, too, so try to pick something you enjoy.

The benefits of adding extra income streams are you diversify your earnings, you can save and so invest more, and you think of yourself even less as someone with a job, and more as an entrepreneur. Mental beliefs are an important part of the picture here.

Don’t dismiss the value of even small amounts of extra income. Any additional passive income streams are valuable when you think of all the capital it would take to earn the same return in a low-interest rate world.

7. Diversify, diversify, diversify

Capitalists know the world is changing fast. Rather than moaning about it, they look for opportunities.

If you can address a strong need someone has, then they’ll pay you for it. Over time we get most of our new gadgets, services, and vices like this.

But that same rapid change that capitalism thrives on – and indeed fuels – is also a threat.

Sentimentalists think we should still be making all our own cars, washing machines, and aeroplanes in factories in each individual country.

Capitalists know global trade has (rightly) ended all that, but they also understand it could be their business that is “creatively destroyed” next.

Rather than hope that laws and regulations can protect your industry – let alone assuming you’ll have a job for life – it makes sense to diversify your skills, knowledge, investments, and other assets.

Be ready for total upheaval, because the chances are it will come at least once in your lifetime.

Getting the right balance is tricky, because capitalism rewards specialists – up to a point. They are more efficient, productive, and usually do a better job. But that also makes them expensive, which increases the chances they’ll one day be replaced by a robot, or cheaper talent in India.

I’ve personally tried to be a generalist for this reason. The alternative is to keep on the cutting-edge of your speciality, to stay young-minded, and to continually seek education and new opportunities.

Don’t fight inevitable change. Just ask the old music label bosses undone by digital file sharing, the engineers replaced by Japanese assembly lines, the IT managers whose jobs have been lost to The Cloud, and so on and on and on.

As for assets, old money diversifies, spreading its wealth. Many new rich people keep it all in one or two assets and either become a lot richer, or go bust.

8. Become an expert asset allocator

One huge reason capitalism works is because it harnesses millions of people’s individual decisions about where to put their capital and effort to best use, as well as what to spend it on.

In communist Russia, comrade Igor and factory chairman Alexander had to decide how many tractors the company would produce in five years. They’d consult with higher-ups in the party and local farmers, and be told there wasn’t enough steel anyway because some other comrade who ran the steel plant was pessimistic and had turned to drink.

These people were just as smart as us, but the system was stupid. They didn’t have the information required to best allocate their resources.

Capitalism replaces all this guesswork and centralised control with prices, which reflect supply and demand. Capital flows to the places where it has the best chance of multiplying, for a given level of risk. Prices of goods and assets change to reflect this.

The system is far from perfect. Despite what academics need to believe to make the sums work, none of us is ultra rationale. Amongst many other things, we get greedy, we get fearful, and we don’t always have perfect information.

As a result, capitalist economies have booms and busts.

Sometimes certain assets and opportunities are too expensive, while others are a steal. Capitalists can make mistakes at knowing which is which, just like two comrades could disagree on the national cabbage target for 1956.

Your job as a capitalist is to try to do a better job at telling the difference between cheap and expensive opportunities. You want your money – your capital – to be in attractive and sustainable places, and you want to pull some or all of it out of areas that look too frothy or, conversely, look doomed.

You don’t want to invest in flaky stocks at the height of the dotcom bubble, but equally you don’t want to retrain as a horseshoe fitter the year before Ford takes motor cars mass market.

Try to be alert to the relative attractions of cash, bonds, shares, overseas markets, and the other assets you invest in.

This is easier said then done, and many investors find they’re better off adopting a passive approach to their portfolio, periodically rebalancing to ensure they don’t become too exposed to fads. This method automatically puts money to work in the unloved – and under-priced – opportunities.

There are allocation decisions to make outside of your share portfolio, too.

Stuck in a country lane for two hours on a Friday night? Maybe it’s time to sell your holiday home. A third person asks if they can buy your antique Aston Martin? Perhaps you should sell it. Can’t sell your Spanish buy-to-let for love nor money, despite deep price cuts? Maybe you should be a buyer, not a seller.

You might not want to sell granddad’s medals from the war (I’m always amazed by how people on the Antiques Roadshow will swap precious heirlooms for two weeks somewhere sunny) but otherwise, all your assets should have a price where you’d sell.

And a price where you’d buy back in!

9. Be flexible

Be open-minded. Money doesn’t care where it’s put to work, and nor does a capitalist, beyond legal considerations and your own ethics.

How many people have daydreamed about opening a cool coffee shop? Countless – there are even books on it . I’d suggest there are probably less over-supplied areas to look towards if you want to get into retail or restaurants. Think creatively.

. I’d suggest there are probably less over-supplied areas to look towards if you want to get into retail or restaurants. Think creatively.

Workers tend to pigeonhole themselves, whereas capitalists are business people first and foremost. Richard Branson is again the supreme example – he’s not just the record shop guy, the airplane guy, the fizzy drink guy, or the financial services guy – he’s all of that and more.

Stay alert to opportunities. They come up in strange places.

As a freelance I earn most of my money from something that began as a hobby when I was doing something else, and I have various other income streams that deliver the same again from assets I own.

I’m not Richard Branson. But I am a capitalist.

10. Minimise your taxes

Capitalists believe that free markets – and companies and consumers expressing their choices and voting with their wallets – deliver the most productive allocation of humanity’s resources.

That’s not to say markets necessarily deliver the “best” allocation, because the word “best” is so subjective.

I’d personally prefer half the money spent on cheap clothes in Primark went on conserving the world’s rainforests, for example, but few shoppers would agree.

What if 90% of people in the world got 100% richer but 10% got 50% poorer – would that be good or bad?

If you were one of the unlucky 10%, you’d probably think it was bad.

What if that 10% wasn’t at the bottom of the pile, but rather they were the richest? Is your answer different now?

This sort of conundrum – invariably combined with self-interest – is why even close friends rarely entirely agree about politics and economics.

I have dear friends who will find this whole post horrendous! The fact is though that I believe the private sector will deliver better outcomes in most cases. Even for some thorny issues. In my ideal world, beyond a safety net for all citizens, government is mainly about setting the rules for society to get the results the majority want.

Cleaner lakes and rivers? Less fat cats in the boardrooms? More houses? Fewer people dying of heart attacks? The State doesn’t need to make that happen through the public sector. Change the rules and set the right incentives, and smart entrepreneurs will find a way.

The logical conclusion is that a capitalist believes she knows better how to spend her money than the State does. Money is better off in our hands.

It’s a legal requirement to pay your share of the taxes, and I’m not suggesting otherwise. But there’s a big difference between tax evasion and tax avoidance.

A capitalist doesn’t donate money to the public purse – not when he or she believes it’s better being put to work by hungry entrepreneurs and companies. I don’t believe in a zero-sized public sector, but with the government already taking more than 40% of the UK’s GDP, I think it’s got enough to be getting on with.

Besides, if you’re taking the risks, why should the State take a big slug of the rewards?

Always take into account capital gains tax and taxes on income. Paying high taxes on your investments makes a big difference over the long term.

11. Give something back

My comments about taxes may have riled some readers, but I’m not praising personal gluttony and excessive hedonism.

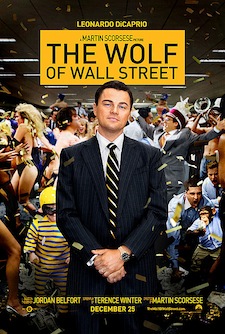

I’ve not once mentioned driving sports cars, bathing in the milk of alpacas, or guzzling expensive champagne with high-class strippers (whether Wall Street asset strippers or the more traditional variety).

Although who wouldn’t want some that now and again? Perhaps not all the same time.

Whatever, it’s a personal choice that has nothing to do with capitalism. Many communist and socialist legends could spend money with the best of them on the backs of the workers. Plenty of capitalists have been wildly greedy, but Bill Gates has devoted the rest of his life and fortune to philanthropy, and Rockefeller didn’t drink or smoke.

Nobody succeeds in a vacuum. A healthy, educated population, family and friends, infrastructure, and the rule of law – none of this comes cheap. That’s why I’m happy to pay a fair share of taxes, and why I think it’s good to give something beyond that to causes that are meaningful to you.

Plus it feels good to spend your money helping others.

Some of the greatest modern mega-capitalists including Gates, Warren Buffett, and Mark Zuckerberg have pledged to give away at least 50% of their fortunes to philanthropy. Others work behind the scenes – and yes, a few inevitably want their names above the wing of a hospital or library.

Who or what would you like to help if you were wealthy?

Thinking about it might just help you get there.