The standard story is that when equities collapse we should be saved by our bonds. Like a financial Clark Kent, this hitherto unassuming asset class takes off its glasses, reveals its cape, and soars above the chaos, lancing losses with laser beam glances.

The so-called flight to quality – when capital deserts risky equities to take refuge in high-grade government bonds – worked during the meteor strikes of 2008-09 and 2000-02.

But – oh big surgery-enhanced buts – it doesn’t always work.

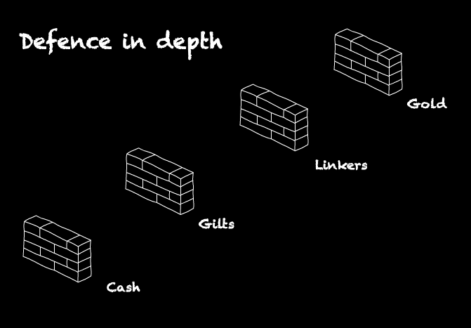

UK equity and gilt returns since 1899 reveal that bonds are not always enough. Our portfolio defences need to be multi-layered like a castle, with walls, moat, archers on the ramparts, and pots of boiling oil ready to meet the potential threats.

How often do bonds rise to the occasion?

UK equities have ended the calendar year with a loss 43 times between 1899 and 2018 according to the Barclays Equity Gilt study, the go-to source for UK returns data.

That’s a timely reminder that you can expect to see an annual loss on your allocation to UK shares around one year out of every three.

So how often have UK government bonds (or gilts) proved an effective remedy for that portfolio pain?

For each year that ended with a loss for UK equities, gilts:

- Rose 28% of the time.

- Fell by less than equities 37% of the time.

- Lost more than equities 35% of the time.

Two-thirds of the time you’d have been better off holding some gilts versus 100% equities during a down year – but even our safe haven bonds would have made things worse a third of the time.

Not ideal.

Do gilts save their best for darker days?

When equities lost 10% or more in a single year,1 gilts:

- Rose 25% of the time.

- Fell by less than equities 65% of the time.

- Lost more than equities 10% of the time.

This is more like it! Gilts made a bad situation worse in only 10% of major market corrections. Nine times out of ten owning gilts cushioned the blow.

When equities lost 20% or more in a single year, gilts:

- Rose 40% of the time.

- Fell by less than equities 60% of the time.

- Gilts have never underperformed equities in this scenario.

UK equities have lost more than 20% in a year on five occasions. Gilts didn’t do worse in these years but the airbag left you in a body cast three times. Double-digit inflation was running amok in each case – 1920, 1973, and 1974. Gilts got trampled like a traffic cop trying to halt King Kong.

To put some gory numbers on the UK’s biggest horror show:

- UK equities lost -71% between 1973 and 1974.

- UK gilts fell by 50% between 1972 and 1974.

You’d struggle to live on those crumbs of comfort.

As mentioned, gilts did register gains during the Dotcom Bust (2000 – 2002) and the Global Financial Crisis (2008 – 2009). Not by enough to fully cancel your losses if you held a 50:50 equity/bond portfolio, but enough to help you pay the bills and buy equities during the fire sale.

Just add cash

The problem is our memories are short and the textbook performance of quality government bonds during the last two meltdowns can easily blind us to the fact that gilts haven’t worked one third of the time.

Can we solve the problem if we diversify into other defensive assets as well as gilts?

Cash has lost value in real terms every single year since 2008. That dismal record might easily stop us digging deeper to learn that cash scored better annual returns than UK equities and gilts in 27 of the 43 drawdowns – or 63% of the time.

Note: The Barclays Equity Gilt study uses UK Treasury bills2 as a proxy for cash.

Cash looks worth holding because:

- Gilts and equities were both down 72% of the time in a losing year. But adding cash meant that you’d have at least one asset in positive territory 51% of the time.

- Cash outperformed bonds 65% of the time when equities lost more than 10% over the year.

- Cash outperformed bonds 80% of the time when equities lost more than 20% over the year.

- Cash beat bonds during all three of the supply shock years – 1920, 1973, and 1974. Cash was still down in real terms, but by much less than equities or gilts.

Index-linked gilts for anti-inflation

Might we improve our portfolio’s resilience with index-linked gilts?

These inflation-resistant government bonds (called ‘linkers’ by their fans) have only been around since 1983, which is a pity because they would have been more popular than flares in the 1970s.

- UK equities have had ten down years since ’83.

- Linkers only outperformed conventional gilts twice. And linkers were still in the red both years, just marginally less so than gilts.

- Linkers ended down when equities lost over 10% in 1990, 2001, 2008, and 2018.

Index-linked gilts did register a small gain in 2002, when equities lost 24.5%. But all told they’re no replacement for conventional gilts as a safe haven.

With all that said, linkers are the only asset class regularly cited as offering useful protection against high and unexpected inflation.

Don’t expect equities, property, or most commodities to help when inflation is off-the-hook. Gold might assist, but not reliably so.

Talking of gold…

Gold for chaos insurance

Gold is famously uncorrelated with equities or bonds. It sometimes works when nothing else does.

We can take a look at whether gold improved a portfolio’s return during every UK equity market drawdown since 1970, thanks to the amazing Portfolio Charts.

There were 15 down years between then and now. Gold, equities, gilts, and cash all sunk together only twice – just 13% of the time.

Gold improved the portfolio return two-thirds of the time.

It did a spectacular job in the stagflationary 1970s. But it’s impossible to know how connected that performance was to the ending of US political controls on the yellow metal in 1971.

Gold also put in a good shift at the height of the Global Financial Crisis. It returned 90% between November 2007 and February 2009.

What’s less well remembered is that gold fell 30% in October 2008, swirling in the same toilet bowl as everything else. Year-end returns can only tell us so much about what it’s like to be a forced seller in the midst of a crisis.

There are many reasons to be wary of gold. It’s not a good inflation hedge for small investors and it has a long-term track record of low returns and high volatility – the opposite of what we want in an asset class.

But gold’s reputation as a safe haven holds up, on balance. Passive investing champion Larry Swedroe sums up the evidence:

As for gold serving as a safe haven, meaning that it is stable during bear markets in stocks, Erb and Harvey found gold wasn’t quite the excellent hedge some might think. It turns out 17% of monthly stock returns fall into the category where gold is dropping at the same time stocks post negative returns.

If gold acts as a true safe haven, then we would expect very few, if any, such observations.

Still, 83% of the time on the right side isn’t a bad record.

An asset that counterbalances falling equities 83% of the time is pretty remarkable in my view.

Gold may help you avoid being a forced seller of shares

Cash and gold do not feature in my personal accumulation portfolio because the evidence shows they’re a long-term drag on returns.

Instead, I’ve backed myself to ride out any crisis and to not panic sell if my portfolio heads south for a few years.

Living off your portfolio in retirement is a different ballgame, however.

A deaccumulator must sell to live.3 If a bear market lasts several years then ideally I’d have at least one asset class in my portfolio that’s above water when I need money. At worst, I’d want an asset that I can sell for a marginal loss.

The nightmare is selling equities at a loss over a protracted period and torpedoing the long term sustainability of your portfolio.

Retirement researchers have found that the dreaded sequence of returns risk hurts us most during the period that starts five years before you start living off your investments until about 10 to 15 years into your retirement.4

That period is the red zone for any retiree. Avoiding too much damage to your portfolio during that time is mission critical.

Which leads me to think that cash and gold should join my deaccumulation portfolio alongside conventional gilts and linkers to provide defence in depth when I’m most vulnerable.

Since 1970 there have only been two out of 15 total losing years for equities where all these asset classes ended the year down together.

I doubt I’ll hold more than 6% of my asset allocation in gold. In the deaccumulation red zone I could probably squeeze two years of living expenses out of that. The ever-excellent Early Retirement Now has also mentioned a couple of times that small allocations to gold (5-10%) can mitigate sequence of return risk.

Gold would be a one-shot weapon for me – fired off to protect my other assets from a worse loss. I’d be unlikely to replace it once used because I’ve only got to make it through that first decade or so. I remain firm in my belief that gold is an expensive insurance policy over the long term.

I feel similarly about cash. Again, I can see myself holding a couple of years supply to get through the height of sequence of returns risk.

One of the odd advantages of being a small investor is that I can probably do better than the Treasury bills rate by keeping cash squirrelled in the UK’s best buy bank accounts – refusing to let it rot when bonus interest rates evaporate. I’ve certainly done alright with cash in the last decade using that strategy.

The critical takeaway is that we need to diversify our defences so that the high watermark of a crisis does not flood our equity growth engines. History tells us not to rely purely on equities and conventional bonds to protect our portfolios.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

- There are 20 instances between 1899 and 2018. Okay, okay, I admit I rounded a -9.6% and a -9.8% to -10%. [↩]

- Short-term government debt with maturity dates of 12-months or less. [↩]

- Editor’s note: Ahem. Presuming they’re not following a ‘living off the income’ strategy, which requires a larger starting pot of capital. [↩]

- Peak vulnerability to sequence of returns risk can even last up to 20 years in the deaccumulation stage if you’re a precocious FIRE type looking forward to 60 years in retirement. [↩]