Bonds are among the most confusing and misunderstood of asset classes. This makes it harder to choose a bond fund suitable for your objectives and exposure to risk.

Bonds are often lazily mischaracterised as ‘safe’. They can be anything but. A major problem is the term ‘bonds’ covers a vast menagerie, running from benign to beastly. Yet the bond funds that most of us need can be boiled down to a handful of choices.

2022 has been historically bad for bonds. But we’d still argue they belong in a diversified portfolio, along with equities, cash, and perhaps gold.

It’s all part of weatherproofing your wealth against whatever economic switcheroos come next.

Please see our refreshers on the point of the different bond asset classes and whether bonds are a good investment. Our bond jargon buster is also worth a quick read if you’d like a clear definition of the key terms.

How to choose a bond fund: the quick version

To choose a bond fund that’s best for your needs, you need to match their properties to your investment goals and the threats that could derail you.

The following table maps portfolio demands against the most appropriate bond fund type to fulfill the brief:

| Role | Bond fund type |

| Diversify against deep recession | Long government bonds |

| Protect against rising interest rates | Short government bonds |

| Finance near-term cash needs | Short government bonds |

| Balance current risks vs reward | Intermediate government bonds |

| Protect vs unexpected inflation / stagflationary recession | Short index-linked government bonds |

Note: UK government bonds are called gilts, and the terms are used interchangeably.

That’s the York Notes version of the story. But it’s a good idea to scratch beneath the surface to understand the pros and cons.

Long government bonds, for example, are the best defence against a classic deflationary recession. But they’re a liability in stagflationary conditions.

And while index-linked government bonds are the best protectors against a sudden flare-up in inflation, they come with health warnings. Not all index-linked bond funds are the same. Take the same care when choosing between them as with a sharp axe when chopping wood.

The rest of this post is about understanding what you’re getting into and how to avoid the big bond fund pitfalls.

Bond aid

We favour high-quality government bond funds because they’re the best diversifiers of equity risk. In other words, when equities are down a lot, these types of bonds are the most likely to be up.

By high-quality we mean funds that are dominated by government issued bonds with a credit rating of AA- and above. A sliver of BBB rated bonds in the fund is okay, too.

Short, intermediate, and long refers to the average maturity date of the bonds held by the fund.

Maturity refers to the length of time a particular bond pays interest before the issuer redeems the bond in full.

A bond fund’s average maturity – reflecting all the bonds it holds – influences its level of risk. We explained how that works in our piece on bond duration.

Here’s the cheat sheet on how average maturity influences bond behaviour:

Short bond funds

- Short bonds are less volatile. That is, they experience smaller swings in value (up or down) as interest rates change.

- However, that makes them less beneficial in a recession, because they don’t make the capital gains that intermediate and long bonds do when interest rates fall.

- Short bonds also offer the lowest expected return over time. Less risk, less reward.

- Maturities range between zero and five years. Look up your short fund’s average maturity figure on its web page. It’ll be somewhere between 0 and 5.

Long bond funds

- Long bond values are the most volatile. You can experience a significant capital gain when interest rates fall, or a loss when interest rates rise.

- That typically makes long bonds more beneficial in a demand-side recession.

- They offer the highest expected return over time (for bonds). More risk, more reward.

- Long bond funds are dominated by maturities over 15 years. Average maturity is likely to be 20+.

Intermediate bond funds

- Intermediate funds are the Goldilocks helping of bonds, versus the short and long varieties.

- They are somewhat risky, moderately helpful in a recession, and offer a middling long-term expected return.

- Intermediate funds hold bonds across a wide range of maturities, from short to long, and everything in between.

- Average maturities range upwards of 8+ to the late teens, depending on the intermediate blend you pick.

Next time might be different. We’re describing here the typical behaviour of the various bond fund types. They are not guaranteed to work this way in the short-term or during every economic event. Learn more about bonds behaving badly.

Short index-linked bond funds

- Index-linked bonds offer unexpected inflation resistance that other bond types don’t have.

- Unexpected inflation means high inflation that consistently outstrips market forecasts. This is the most dangerous type of inflation for equities and non-index-linked bonds (often called nominal bonds).

- Index-linked bonds make payments that are pegged to official measures of inflation.

- This should make them useful in stagflationary recessions that hurt equities and nominal bonds.

- But you may have to stick to short index-linked bond funds for reasons explained briefly below, and detailed in our post about the index-linked gilt market’s hidden tripwires.

Young investor bond fund selection considerations

Are you a young (ish) investor who wants to guard against the threat of a deep, deflationary recession? (Think Great Depression, Global Financial Crisis, Dotcom Bust, Japanese asset price bubble).

Then long government bond funds are the best diversifiers for you.

That’s especially the case if your portfolio is heavily skewed towards equities. (Say a 70% or higher allocation.)

Diversification decrees you want the bond class most likely to profit when your big equity holding crashes. That’s long bonds.

Meanwhile a 70%-plus equity portfolio is likely to be so volatile you probably won’t much notice the relatively wild swings of long bonds on top.

Consider the long bond trade-off carefully

The opportunity: Because you won’t withdraw cash from your portfolio for 30 years or more, you can ride out capital losses should bond yields rise. But when the world is laid low by a major recession, you should capitalise on surging long bond values as interest rates tumble.

In this scenario, long bond gains cushion your portfolio from equity losses. We’ve seen bond funds do just that during past market slumps.

Later you can mobilise your bonds as a source of financial dry powder. You sell some bonds to buy more equities while they’re on sale – a technique known as rebalancing.

The threat: Long bonds can suffer equity-scale losses during periods of rising interest rates and when inflation lets rip. This risk has materialised with a vengeance in 2022.

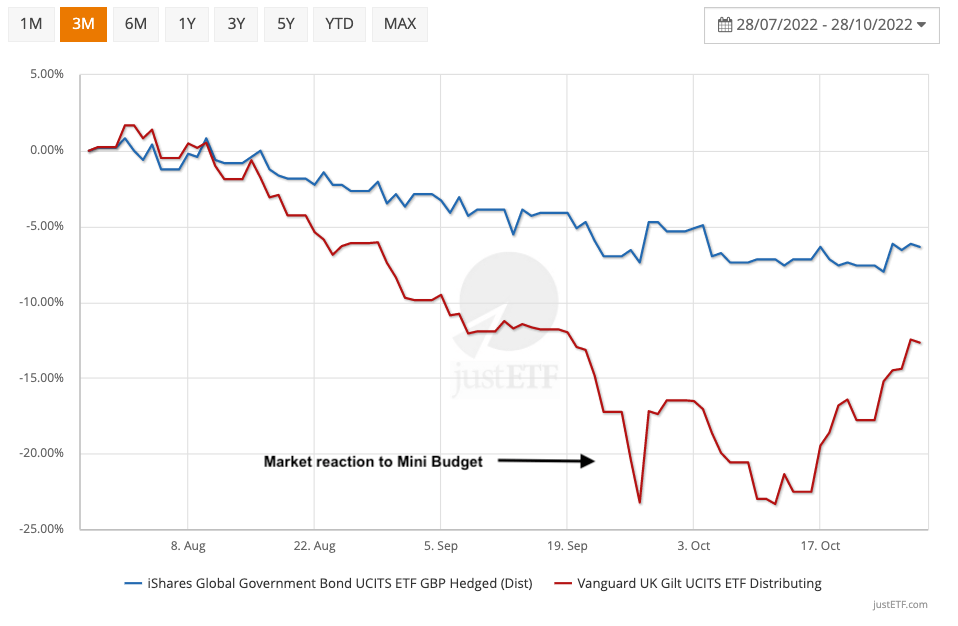

This chart (from JustETF) shows how one long UK government bond fund has dropped 36.5% year-to-date:

Hardly an easy loss to shrug off! Even a young investor should think twice about long bonds given the current balance of risks – the strong possibility of prolonged rising inflation alongside interest rate pain.

That goes double if you’re the sort of person liable to get distressed by individual losses in your portfolio. (Versus viewing it holistically as a system of complementary asset classes that thrive and dive under different conditions.)

Intermediate high-quality government bond funds may offer a better balance of risk and reward for you.

Older investor bond fund considerations

Near-retirees or retired decumulators have a trickier balancing act. That’s because you’re likely to withdraw funds from your portfolio in the near-term.

Short bond funds and/or (especially) cash won’t suffer from a rapid capital loss like long bonds can. So owning them means you’re less likely to face a shortfall that derails your spending needs.

Demand-side recessions are still a threat to a retiree’s equity-dominated portfolio. But adding long bond fund risk on top can ratchet risk to an unacceptable level when there’s less time to wait for a recovery.

Again, intermediate bond funds chart a better course between the threats of rising interest rates and insufficient diversification during a crisis.

But why not just stick to short bonds or cash?

The next chart shows why. This is how short, intermediate, and long UK government bond funds responded during the COVID crash:

As equities caved during the early days of the crisis, long and intermediate bonds spiked almost 12% and 7% respectively.

Short bonds barely registered there was a pandemic on. Cash was similarly indifferent. So while these assets didn’t lose, they didn’t counterbalance falling equities much either.

On the right-hand side of the graph, you can see long bonds came out ahead, with intermediates and short bonds in the silver and bronze positions. Just as you’d expect in a deflationary slump.

Meanwhile – in the middle of the crisis – a whipsaw effect temporarily crumpled all gilts thanks to a sell-off by large investors desperate for liquidity.

It stands as a useful reminder that our investments rarely work like clockwork during a panic.

Inflation protection

There’s no one-and-done, slam-dunk solution to inflation risk.

Anyone who fears uncontrolled, high, and unexpected inflation should consider an allocation to short maturity, high-quality index-linked bond funds.

But young investors with a long time horizon could just inflation hedge using equities.

That’s because the long-term expected returns of equities are higher than index-linked bonds, even after inflation prospects are taken into account.

Retirees, by contrast, are better diversified if their defensive asset allocation includes a slug of short index-linkers.

The twin thumbscrews of rising interest rates and inflation are torture for nominal bonds. Short index-linked bonds are better equipped to take the pain:

- Blue line: This short global index-linked bond fund (hedged to GBP) has returned -1.1% since inflation took off.

- Red line: Our short, nominal UK government bond fund fared worse with a -6.4% return.

- Orange line: But the intermediate, nominal UK government bond fund did worse still. It took a -24% hit in the last eighteen months.

The index-linked bond fund has fared better than its two nominal bond counterparts in an inflationary environment. Just as you’d expect.

What’s surprising is that the index-linked bond fund is down at all. What happened to its vaunted anti-inflation properties?

Index-linked bonds can fall even when inflation rises

The problem is that index-linked bond fund returns are composed of two main elements:

- Coupon and principal payments that are linked to inflation

- Capital gains or losses that are determined by fluctuating interest rates and bond yields

Interest rates can climb so quickly that the resultant capital losses can swamp an index-linked bond fund’s inflation payouts.

This is what has happened in 2022. Hence index-linked bonds haven’t protected our portfolios nearly as well as we’d hope.

In particular, long index-linked bond funds have been absolutely awful these past six months:

The long index-linked bond fund (blue line) is down 26% vs -1.1% for the short index-linked bond fund (red line).

Why? Because the long index-linked bond fund is much more vulnerable to rising interest rates. Its underlying bonds – with their longer maturity dates – are subject to more volatile swings in value when interest rates yo-yo.

That makes a short index-linked bond fund a better analogue for inflation. Though it too suffers (smaller) temporary setbacks from rate hikes.

Which is why I keep saying choose a short index-linked bond fund.

And because there isn’t a short index-linked gilt fund in existence, you’ll have to choose a global government bond version, hedged to the pound.

Hedging to the pound (GBP) removes currency risk from the equation.

Global government bonds or UK gilts?

You also face choosing between high-quality global government bond funds hedged to GBP or gilt funds, which are still AA- rated (at least for now).

We used to be agnostic about this choice. There are good intermediate index trackers available in both flavours.

But then this happened:

Gilts got pummeled relative to global government bonds when Truss and Kwarteng went on their bonkers Britannia bender.

UK government bonds have since climbed someway back out of the hole. Sanity has been restored, but this was a wake-up call. A stiff lesson in the danger of concentrating your risks in a single country.

We Brits proudly think of ourselves as members of the premier league of nations. So was this a one-off shocker or evidence we’re on the brink of relegation?

Your answer to that will determine whether you choose gilts or global government bonds.

Government bond funds or aggregate bond funds?

Another decision!

Aggregate bond funds cut high-grade govies by mixing in bulking agents like corporate bonds. The upshot is you gain a little yield but you give up some equity crash protection.

Crash protection from bonds is paramount in my view, therefore I favour government bond funds.

Our piece on the best bond funds includes ideas for intermediate gilt and global government hedged to GBP bond funds.

And when you do come to choose a bond fund, this piece on how to read a bond fund webpage may help.

Hedged or unhedged?

Should you choose a global bond fund, we think the argument is tilted in favour of selecting one that hedges its returns to the pound.

In other words, you’ll receive the return of the underlying investments unalloyed by the swings of the currency markets.

Bonds are meant to be a haven of relative stability in your portfolio. (Even though that hasn’t been the case for many of us in dystopian 2022.)

If you invest without hedging then you’re exposed to currency volatility – on top of whatever else might be knocking your bond investments around. Such currency moves may work for or against you. It’s lap of the gods stuff, despite what that nice man on YouTube says.

Hedging removes currency risk. Probably a good idea in the case of bonds though probably1 a bad idea for equities.

Hedging is particularly sensible if you’re a retiree who can do without their bond fund plunging just because some loony gets installed in Number 10 and tanks the pound.

Obviously UK-based investors don’t need to hedge gilt holdings. They’re valued in pounds in the first place.

Go West, young man (or bond-buying woman)

There is a nuanced argument that younger investors might want to choose to invest in unhedged US treasuries – or at least that those young investors who are very hands-on with their portfolios could consider it.

That’s because US government bonds and the dollar often benefit from safe-haven status during a crisis. As such, returns from unhedged treasuries may temporarily outstrip any gains from gilts valued in sterling.

If they do then you can sell your treasuries and pop the proceeds into gilts, potentially adding a kicker to your overall return.

Historically, however, gilts have then reeled treasuries back in over time. So this ploy probably isn’t worth the trouble for proper passive investors.

How to choose a bond fund: model portfolios

Here’s some asset allocations devised in the light of all these ‘how to choose a bond fund’ ideas:

Young accumulators

| Asset class | Allocation (%) |

| Global equities | 80 |

| Intermediate global government bonds (GBP hedged) | 20 |

Long bond funds are technically the best diversifier but we think that the threat of high inflation and continued rising interest rates makes them too risky right now.

There’s a more nuanced approach that involves holding a smaller allocation of long bonds while attempting to dampen the risk with an accompanying slug of cash. Read the Long bond duration risk management section of this piece if you want to know more.

Older accumulators / lower risk tolerance

| Asset class | Allocation (%) |

| Global equities | 60 |

| Intermediate global government bonds (GBP hedged) | 20 |

| Short global index-linked bonds (GBP hedged) | 20 |

Equity risk is cutback while unexpected inflation protection is introduced. Note that index-linkers are nowhere near as effective as nominal bonds during a deflationary, demand-side recession.

Check out our other ideas on improving the 60/40 portfolio and managing your portfolio through accumulation.

Decumulators – simple

| Asset class | Allocation (%) |

| Global equities | 60 |

| Intermediate global government bonds (GBP hedged) | 15 |

| Short global index-linked bonds (GBP hedged) | 15 |

| Cash and/or short government bonds (Gilts) | 10 |

Decumulators use cash / short government bonds for immediate needs, equities for growth, intermediates as shock absorbers, and linkers for unexpected inflation defence.

Decumulators – max diversification

| Asset class | Allocation (%) |

| Global equities | 60 |

| Intermediate global government bonds (GBP hedged) | 10 |

| Short global index-linked bonds (GBP hedged) | 10 |

| Cash and/or short government bonds (Gilts) | 10 |

| Gold | 10 |

This portfolio adds gold to the armoury of strategic diversifiers.

Gold isn’t an inflation hedge per se. But it has worked relatively well in two rising rate environments that have hammered nominal gilts (the 1970s and now).

“I think interest rates will continue to rise…”

Okay, if you’re sure rates are headed higher then stick to cash.

Or if bonds seem too scary at the moment then stick to cash.

But remember that ever since the Global Financial Crisis ushered in near-zero interest rates, cash has done little more than protect your wealth in nominal terms.

You’ve lost spending power after-inflation with cash, whatever your bank balance says.

Look, we get it. 2022’s historic kicking for bonds has been so savage that even ten-year returns are lousy for many funds.

But it would be bold – to say the least – to bank on a repeat performance over the next ten years.

The expected returns from cash are worse than bonds over the long-term.

Cash is not a free pass.

If you don’t believe you can predict the future course of interest rates (you can’t) then put your faith in diversification.

If you’re still not sure, maybe split the difference: some cash, and some bonds.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

P.S. If you’d like to know more about bonds then check out these posts:

- How rising bond yields improve returns over the long-term

- What bond duration tells you about your fund’s risk level

- How interest rate shifts affect bond prices

P.P.S. When we mention ‘interest rates’, we’re referring to bond market interest rates, not central bank interest rates. References to ‘yield’ mean yield-to-maturity. Please see our bond jargon buster for more.

- We are saying “probably” here not because we can’t be bothered to consult a textbook, but because the case isn’t clear-cut and nobody knows the future. [↩]

Thanks Monevator! As always appreciate your effort!

I’m a long time reader but haven’t commented before, currently wondering whether to ditch bond funds and buy the bonds directly (creating my own bond ladder) so I can hold to maturity and not worry about the drop in price.

This is mostly driven by having no idea how the coupon redemption works in a bond fund. I suppose my question is does anyone know of the advantages/disadvantages to this and how easy it is to set up a monthly buy order for the latest government bonds?

@Martin — I’m seeing a lot of people talking about owning gilts directly instead of investing in a fund.

And there can be benefits, such as you can be very specific about exactly what you own (duration, yield to maturity, and so on) and in particular if you’re trying to match a particular required and known stream of income in advance.

But it’s important that more casual bond ‘tourists’ don’t think there’s something magic going on here.

An ETF or index fund comprised of gilts just contains a basket of gilts like you would buy in the market yourself. The only (potentially very big) difference is it regularly sells/redeems gilts and purchases new issues in order to maintain the mandate of the fund.

So, for example, an intermediate bond fund would sell bonds as they became too short and replace them with longer-dated bonds in such a way as to maintain its desired duration posture.

Obviously the same thing would happen if you owned a basket of bonds yourself that you wanted to maintain at a particular duration, except that you’d probably pay higher costs and have more hassle.

Aha! But you wouldn’t, you are going to hold to maturity? This way you will avoid capital losses!

Okay, that seems like a canny move after 2022, I get it.

But remember that you only avoid capital losses if, yes, you hold to maturity AND if the bond was priced below its par/face value when you bought it.

Mostly no worries about buying below face value today. But if you’d undertaken this two years ago then you could well have been buying gilts at well above their par value – guaranteeing a capital loss if you held to maturity.

Over time such bonds would have suffered capital losses to redeem at par, either quickly (as we’ve seen in 2022) or slowly (over several/many years), with (presumably, given you bought them) the coupon payments sufficiently offsetting some or all (at a point yields were negative, so maybe just ‘some’) of your capital losses.

In other words, people seem to be taking the view that 2022 has shown bond funds are a bad idea.

But if you want to take a lesson (and even this certainly has two sides, as shown in @TA’s many articles and above) I’d say it’s more that buying bonds at negative yields to maturity is a bad idea, whether you buy them directly or via a proxy within a fund.

The other important thing to remember is that yield-to-maturity is what matters — which comprises both income and capital returns — not capital losses per se.

If a bond’s income is sufficiently high (to you, regarding *your* goals) to compensate you for a baked-in capital loss, as represented by the yield-to-maturity, then the capital loss doesn’t matter.

This is a good read through the lens of hindsight, from June 2020. It shows that the potential for what we’ve seen in 2022 was in the price at the time:

https://monevator.com/negative-yields-bonds/

In reality, 2022 has been worse for bonds than almost anyone anticipated. It’s been as bad as almost anything in the history books.

Still, note that @TA said even in that piece (which was broadly pro-bonds for crash protection reasons): “I’m using a negative real expected return for bonds – I don’t think hoping for the historical average return is realistic.”

For all of us 2022 has been a learning experience. However it would be a mistake IMHO to change one’s approach to bonds based on a very extreme year, coming off very extreme circumstances (negative yields across the developed world).

@investor – Thanks for the detailed response! As you said 2022 has been a tough year for bonds which is why I’ve been evaluating my current strategy!

Will probably end up doing nothing and letting the automated purchase orders work their magic, however bonds are an area I don’t understand as well as equities which is why your articles are so useful!

I have in my bookcase and recommend if you don’t own it, “The Sterling Bonds and Fixed Income Handbook” – Mark Glowery – first published by Harriman House in 2013 and available from Amazon Books and others. “A practical guide for investors and advisors”.

No connection with author or publisher etc.

Thanks for the detailed and informative article as always.

The big problem with UK government gilts (and hence gilt funds) at the very least up to 5 years term is that they don’t offer as good an effective interest rate as equivalent best buy savings accounts. And that’s been the case for many years. Probably the reason they are poor value is to do with certain institutional investors such as pension funds needing to hold gilts to match liabilities hence bringing down the returns (but I’ll leave those sort of explanations to others)

In essence (there are many differences of course) you can think of UK government gilts as savings accounts that you can buy and sell in the market.

And at time of writing for example the 5 year redemption yield on a UK gilt is around 3.54% pa while the best buy 5 year fixed ISA is around 4.3% pa (and around 5% pa for non ISA best buy 5 year accounts).

And with gilt funds you’ve got charges to add in as well, albeit they don’t amount to that much, and it’s the differential effective interest rate that is the real issue.

To state the obvious a 0.5%pa difference in effective annual interest rate very roughly amounts to losing 10% of your gilt investment over 20 years compared with using savings accounts.

It is sometimes said that the lower returns on gilts (vs savings accounts) are made up for by a magical rebalancing bonus to be had by keeping the proportion of the value of the portfolio invested in equities and gilts constant over time. If that is true (it’s nuanced in my view, but there is some potential truth in that) you could achieve the same thing with savings accounts, e.g. by moving money out of savings accounts when equities suffer a significant fall (e.g. when fixed term accounts mature after a significant equity price fall moving the savings maturity money to equities).

Let’s also note that you do have access (with penalty) to money in most fixed term cash ISAs before the fixed term ends. And at the moment because interest rate expectations have increased significantly in the past year it is often worth paying that penalty to switch to a higher paying account over the original outstanding term where the additional future interest considerably outweighs the penalty. So with ISAs you essentially usually have an option against the savings provider on longer term accounts should interest rates significantly increase.

While you can sell government gilts at any time (whereas a fixed term account might only be accessible at the end of the term), does that really matter if this is money that is only needed in the distant future?

Of course there can be practical difficulties with best buy savings accounts, for example you can’t really access them through money within a pension, but I think in most cases it should be possible to structure your assets to use your non-pension assets for the savings accounts element.

And when we talk about gilts over 5 years term, while there may not be good savings accounts of equivalent term you are still losing out because the institutions essentially still drive up the price for gilts and hence reduce returns below that of what such savings accounts might offer over the long term.

I don’t and have never held gilts (and have always chosen savings accounts as a way of watering down risk) so I have a cognitive bias against gilts that I have to fight. But at the same time I’ve never seen a credible argument to persuade me to reconsider at least in relation to my own assets.

@accumulator

I will be retiring in my early 40s in Southeast Asia. Due to this in my ISA and pension I have used unhedged global bonds and my portfolio has no UK home bias. My thinking is that the £ won’t be my local currency and so I don’t want to tie myself to it. Additionally, as my local currency is an emerging market, I don’t want to hold a bond fund in it. What is your view on hedged vs unhedged if your local currency is not GBP and you don’t have a suitable local alternative?

As a side note, once I live there, I am also considering a rolling 3-year bond ladder using local government issued debt. This would be included in my total equity / bond ratio.

@ Martin – this piece is worth a look on what happens when yields rise: https://monevator.com/rising-bond-yields-what-happens-to-bonds-when-interest-rates-rise/

The only point in holding individual bonds is if you expect to use the money invested to pay a specific liability when they mature (e.g. your annual expenses for the year 2030). If you don’t have a specific end date in mind for the money and will just reinvest as the individual bonds mature then it’s a bond fund by another name.

@ Snowman – I agree with you that I’d rather hold cash than short nominal bonds if I can – that was the motivator behind writing cash / short bonds in most instancesb where that applies.

Just a few counterpoints for balance and debate more than anything:

The same analogue doesn’t exist for index-linked gilts without our beloved index-linked National Savings Certs. (I know you weren’t suggesting otherwise, I’m just clarifying.)

Personally I’ve just been caught out with a fixed rate savings account that I really wish I could redeem now. Circumstances change and it turns out I’m not Nostradamus 😉

Some people do hold significant amounts of cash or cash-like securities in their SIPPs, and that’s when I’d hold short bonds, and maybe money market funds.

Shorter bond funds are also handy for duration matching with bond funds, although cash could do that job too.

Over the longer term, I’d take the crash protection of longer bonds. Be interesting to know what analysis you’ve done though. Knowing you, you’re bound to have spreadsheeted this!

@ Dan H – Interesting! My starting point would be what does my local currency tend to do in an equity market crisis. If it falls vs the dollar then I’d look to hold US treasuries or hedge to USD.

My theory about why the high-street bank savings accounts offer more than gilt YTMs do is that the banks are willing to pay a premium to lure new customers in, knowing that most won’t bother to move once the account’s rate falls below what’s available elsewhere (which always happens eventually), at least until the gap becomes too huge to ignore. The banks have been doing this for decades and have a good idea how sticky customers are, how much it’s worth paying to acquire them and how much can be extracted from them subsequently. Obviously that’s quite exploitable by agile people chasing the best rates, but most can’t be bothered.

@The Accumulator

All good points re savings account vs government gilts.

Unfortunately haven’t created any good spreadsheets here. I just recall every time I’ve looked for many years savings account rates have exceeded the corresponding gilt redemption yield for the same term and that’s put me off UK government conventional gilts.

I recall the Bank of England has historical gilt yield data, but getting hold of the corresponding best buy savings accounts for the corresponding terms is pretty much impossible. So you can’t really work out the historical rate differential on which the ‘best buy savings accounts are better’ argument is based.

And my own re-balancing is very ad hoc. I’ve moved from almost 100% equities to 70% equities/30% cash over the years. I have a real return figure calculated based on the return needed for me not to run out of money during my lifetime (ignoring contingencies like house ownership as your house is not an asset ha ha). I’ve generally tended to reduce the equity percentage on an ad hoc basis as my required return came down and then went negative.

So while I talk about being able to adjust the amount in savings to mirror what would happen if investing in gilts and maintaining a consistent asset proportion, it’s not something I’ve done in practice and I’m just pointing out it could be done. My issue with rebalancing assets is in any case what happens if one of your asset categories becomes gradually worthless in some extreme scenario or at least suffers a continual decline over your lifetime; you are going to funnel more and more of your assets into that asset category, at what point do you stop?

Psychologically it’s annoying if you get a fixed rate account and then future interest rates go up and better rate fixed rate accounts are available and you are stuck with the lower interest rate. But of course if you had bought a gilt instead of the same term its price would have gone down following that interest rate expectation rise or if held to maturity would have left you with a similarly low return while you held it.

I’ve missed out on national savings certificates when they were available, there were some good rates available once. I’ve found it difficult to invest in index linked gilts while they are providing negative real returns. But I wouldn’t disagree with someone saying a holding in index linked gilts is a good idea, and makes more sense to me because there is no savings equivalent currently. It always amazes me that people will prefer a 5% savings rate when inflation is 10% than a 2% savings rate when inflation is 2% when their future income requirements are inflation linked.

Whilst interest rates are increasing/bonds falling, holding a Global Equity fund and Cash (at your chosen asset allocation) works well with Vanguard as they are currently paying around 1.8% (after platform fee) on the cash.

Presumably as rates rise this will increase.

Once rate increases seem to have topped, you can revert back to Bonds.

@snowman

You might consider Vanguard’s Short £ Investment Grade Bind fund. ( Vanguard professional web site shows the portfolio characteristics) cost .12%, ytm is 6.1% credit quality is A+ it’s not gilts but not junk by any means, 400+ holdings, UK holdings are a minority , the price has fallen this year as yields are sharply higher but worth a thought…

@TA Great post as ever.

I totally agree that it is a good idea to hedge foreign bonds in general to reduce the currency risk in the portfolio, and especially for the part that is supposed to be lower risk.

However, I wonder if the same is true for the inflation-linked part. If there is high inflation in the UK but not abroad then a Hedged Global I-L Bond fund will not provide much solace as it reflects the inflation in the other countries (mostly US). But in such circumstances of higher UK inflation it it likely* that GBP will fall in value versus other currencies. For a non-hedged fund this would bring some compensation to match the inflation, as a mostly USD fund will rise in value as GBP falls.

I am not sure if there is any real evidence of this as I don’t think UK inflation has been substantially different to other developed countries in recent years, but the way things are looking…??

* similar caveat as you use in the post – markets don’t always react as they are “supposed” to do!

Apologies if this maybe isn’t the right thread. For a long time I’ve wanted to remove the home bias in Vanguard Lifestrategy by switching to a world equity fund plus two bond funds (global government bonds & global index-linked).

My question is – is it a ‘good’ time to sell the LS60 and put 40% into the 2 bond funds? I understand that the LS60 (for example) has lots of corporate bonds and only 3.4% of the bonds are index-linked – ie it wouldn’t be swapping like-for-like Any comments gratefully received.

Where would you see something like a active managed strategic bond sitting ( if at all) in the mix for young or decumulator portfolios?

I’m thinking of ( as UK investor for my Sipp ) below in a blend about 30-35% of my PF with rest in Equity

1. IBTG hedged to GBP 1-3 year Treasury while yield inversion

2. IBTL 20 year non hedged treasury for recession – sell to buy cheap equity

3. And thinking need middle ground of something to cover other bond offerings lower ratings, Europe , UK EM markets – RL Global opportunity, Alliance Strategic Bond, Twenty Dynamic Bond or something like CG Dollar Fund or CG Real Return hedged funds with current duration about 7 years.

Any comments on this ?

Appreciate DYOR

Best

MrBatch

Sorry if veering off-topic and a bit too in-the-moment, but:

why is the bond market asking for interest of around 4% when inflation is around 8%? (don’t investors at large care about this loss?! I assume for longer bonds they are asking for an average of 4% and they expect inflation to collapse, but shouldn’t, say, a 1-year yield be relatable to something like inflation in the moment?)

Another helpful article on bonds!

How does the young accumulator turn into an older accumulator – other than by acquiring grey hairs and chronic health conditions? Is this a matter of gradually adjusting allocations when the time comes to rebalance? I’m interested in how people manage these transitional phases, in particular during volatile markets (such as this year), when you might end up selling funds (e.g. intermediate/long bonds) while they are down.

Perhaps this is just another variant of sequence of returns risk?

@TA:

Not sure who said it, but apparently the best time to buy something is when nobody else is buying it!

@Meany — If you don’t like the c. 3.5% yield you can get on a two-year bond, then you are perfectly at liberty not to invest in them. 🙂

What’s that? You don’t have much other choice?

You can only get <2% on an account with instance access? You want some safety buffer in your portfolio but you don't want to risk long duration bonds? You'd prefer not to lock your money away for two years in a fixed-rate savings account? You have too much -- six or seven-figures -- which is beyond those account limits? (Or are you asking on behalf of the company you work for, which has tens of millions of pounds in cash reserves?)

Hmm, then maybe you'll have to go and buy that two-year bond after all.

I don't mean this, um, meanly. 🙂 I am putting it this way to show that these yields result from the interplay of various factors in the market, and supply and demand. It seems like a trivial point but it's really *the* point.

It's also why it's best to think in terms of a yield curve of market interest rates, rather than to silo your thinking into little buckets of this or that, if you really want to try to see what the market is telling us.

Incidentally, your intuition about long bonds is quite correct. The market expects inflation to be back to target in a couple of years.

If it isn't they'll get mullered, which is one reason why yields spiked so much during the five-second era of Trussonomics (though I'm still convinced the optics looked worse than pure 'market judgement' due to the LDI distress...)

Hope that makes sense.

@TI, thanks for your thoughts.

it must be that somehow yield ~3.5% is the agreed compromise of sellers and buyers. I’m not sure if the government are getting a bargain, or maybe they always do quite well but the effect is exaggerated when inflation jumps up.

@Dalek, I think the ideal is to make these allocation changes when the new fund has better prospects than the old one. So I might switch VLS100 to VWRL if VLS100 has fallen less this year (think that’s true), but the uk bond excess in VLS60 has probably made the bond part fall more than the balanced global bond fund you want to buy. So, I’d do the calc of whether the new fund combo has fallen more or not, then hum about whether I believe in the switch enough to lose the difference if it’s not favourable.

@Meany — I do think it’s an interesting point, but remember the UK like other developed world countries has been living with negative *real* rates for many years. We’re tending to pay renewed attention now both rates and inflation are higher — and yes, current inflation is *very* high — but real rates have been on the side of borrowers for most of the past 13 years. (See my articles on getting and running my big interest-only mortgage, albeit that’s looking a bit less compelling on the repayment side after the recent mortgage shocks!)

As for whether the government is getting a good deal, I suspect as you say it does tend to, but then we demand it borrows and spends money on services we arguably can’t afford so we’re all in it together! 😉

But it’s worth noting that persistently higher than expected inflation isn’t great for the UK finances due to our relatively large stock of index-linked gilts. From memory they comprise about a quarter of gilts outstanding, but high inflation means that even with low yields they’re now making up about a half of the UK’s interest payments.

Really the government should have issued a trillion in very long-term nominal debt at 0.5% or something during early 2020, and earmarked the majority for investment (e.g. green revolution). I suppose there might be good reasons why it didn’t, but some of us not knowledgeable enough to be certain of what suggested it at the time and events have gone in our favour.

On the other hand many would say that would have only made the inflation picture even worse. However if the money had been genuinely targeted at infrastructure etc not too much would have been spent by now, and in practical terms a big chunk of debt could have been refinanced, including perhaps some of this index-linked stuff

I should stress I’m no expert on government debt/financing, just enjoying the conversation etc. 🙂

@Meany – thanks, you’ve nailed my concern by saying ‘does the new fund have better prospects than the old one?’ but I’m cautious of making an ‘active’ decision.

I should have given a clearer example:

Say I have UK government gilts but agree that (as mentioned above and on the S&S Q3 update) a more diversified and passive approach is to hold world government bonds.

Is it a good time to make this change? Have UK bonds been more adversely affected by the recent troubles, and therefore might have a better prospect of recovery *from this point* than world government bonds?

@ Moo – Cheers! I looked into the question of how closely UK inflation was correlated to other country’s inflation rates when I made the shift to a short global index-linked bond fund. The answer was it was highly correlated.

Remember we’re talking about highly interconnected developed markets here and we have a very open economy. UK linkers are also a big slug of global linker’ funds holdings. We have a large linker market and from memory UK bonds are the second biggest holding in the funds I looked at.

Ultimately the objective here is to get the best short-term analogue for inflation you can and so I’d rather avoid layering currency risk on top.

The other way of doing this would be to DIY and create a rolling 3-5-year ladder of individual index-linked gilts. That would solve the problem. I need to get on and write that piece about building your own bond ladder.

@ Mr Batch – what’s the problem you’re hoping active management will solve?

@ Haphazard – after reading lots about gradual transitions, my two major rebalancing acts came in the aftermath of market lurches which made me realise I was less brave than I thought.

For me, it happened once I felt I really had something to lose. For example, once I’d accumulated enough to pay off the mortgage or was 75% of the way to FIRE. In the case of the mortgage, I’d have been much better off (financially) staying in equities but I’m very glad I did not.

The stress of watching that money evaporate would have been too much.

@ Dalek – it sounds to me like you’re making a strategic shift and you’ll be content to hold that position for years after? If so then I say plough on and ignore whatever temporary lurches the market makes in the aftermath. They could work for you or against you but you can’t control them. A few years hence they’ll look meaningless. There’s never a ‘right time’ as such. The world is constantly in turmoil, so it’s better to make your move and be confident that you’re choosing an allocation that suits your situation in the long term.

@ The Accumulator Post 23

Really whether the more complicated stuff (corporate bond, credit, High Yield, Emerging market bonds etc ) is best handled by active manager ie TwentyFour/Vontobel, RL, Allianz, Capital Gearing etc or best avoided and just go for cheap etf for hedged short Tbond/TIP/short Gilt, unhedged 20year us treasury with cash to manage duration down

@TA – Thanks. Yes, a strategic shift

I’m curious – might there be change a similar strategic change reflected in the Slow & Steady portfolio at some point?…

I often find the ‘when to press the button’ passively difficult. You’ve written about lump sum vs drip-feed before and I’ve understood that lump-sum is usually better. I save funds into my ISA as soon as they’re available, but have constant arguments with my better half, who sits uninvested waiting for a ‘better time’, sometimes for long periods, paralysed with indecision.

Another option re: global inflation-linked bonds for those who aren’t ultra-wedded to owning the whole market, passive-style, is to just add (/swap into) a big chunk of US TIPS, which make up the majority (i.e. over 50%) of the global inflation-linked funds I can recall looking at.

You could sell some UK linkers and swap into the US 0-5 year TIPS ETF from iShares which has a duration of less than 2.5 and really pull down overall duration. From memory even the standard TIPS ETF from iShares (ITPS) has a duration of 7-8.

Of course you do forego the inflation-linked bonds from France and Italy and Japan and so forth. From an ‘owning the market’ and diversification perspective that’s certainly downside, and I can foresee @TA coming along to rap my knuckles in a moment.

But you do perhaps get some ‘flight to quality’ benefit from focusing on US TIPS, too, I’d imagine, as per @Finumus’ recent piece.

@TI – Interesting. I recall shifting my UK linkers to global ones (RLAAM) in line with the prescient strategy shift in the Q1/2019 S&S update…

https://monevator.com/the-slow-and-steady-passive-portfolio-update-q1-2019/

I’m wandering off-topic here but a last bit on the cost of TIPS/Linkers to governments here:

https://riskyfinance.com/2022/10/21/when-linkers-bite-back/

@TA, @TI, loved the article and the responses. I know what kind of bonds I am happy with – U.K. intermediate gilts…

… what I didn’t see in your analysis of bond funds vs bond ladder was my fear that individual investors might sell bond funds when they fall leading to the fund selling bonds to meet redemptions thereby crystallising a loss ?

Is this a concern ? I don’t want to set up a ladder but it does rankle

@ TI – Where’s my ruler? Actually, just eyeballing the available TIPs ETFs, this looks worth further investigation: iShares USD TIPS 0-5 UCITS ETF GBP Hedged (TI5G) available for a very reasonable 0.12%.

It did better than the short global hedged linker ETF mentioned in my piece too. 0.37% vs -1.1%. It’s shorter duration so less real interest rate risk.

What I like about global linker funds is they have gilts in them so should better reflect UK inflation. The Royal London fund is shorter duration then the one quoted in my piece. Be interesting to match that up against TI5G.

@ Mr Batch – The evidence I’ve read indicates those additional bond asset classes have lower long-term returns than equities and little to no diversification benefit in a crisis so I don’t think there’s any need to hold them. Might also be worth looking at the US SPIVA study which typically shows active bond fund managers being pwned by passive over time.

Note, I’m not against active funds when they have a strategic role to play. I’ve owned a short-term global index-linked bond fund by Royal London plus risk factor funds.

@ Dalek – drip-feeding into a position often helps overcome the psychological barriers you describe. You could move a chunk every month or every quarter.

I’d guess “waiting for a better time” means when the market is rising again i.e. when assets are more expensive than they were. It’s a very human instinct but it’s the opposite of buy low, sell high.

I found the maths in this piece useful – might be a helpful one for your partner:

https://monevator.com/pound-cost-averaging-the-buy-low-superpower/

@BBlimp – Cheers! If I buy a share in an open-ended fund it uses the cash to buy whatever underlying asset the fund tracks e.g. world equities, gilts etc. If you then come along and buy into the fund, same thing happens. Now you sell. The fund sells enough of the underlying asset to return whatever your share is now worth. But it still holds enough assets to cover the value of my share. I haven’t crystallised a loss because you’ve sold. My assets are still worth whatever the market thinks they’re worth. Once the market rises again, or rolls up enough dividends/interest, then the value of my share rises.

The same wouldn’t necessarily be true of a close-ended fund. Index funds, ETFs, mutual fund types – they’re all open-ended.

@TA

Very topical and informative post, thanks.

I’m wondering if anyone has any suggestions they could kindly share on unhedged GBP bond funds / ETFs?

Struggling to find practical ways to buy say short term Treasuries in USD. The GBP share classes of the big ETFs seem to always be currency hedged, reluctant to buy USD share class given FX fees and tax return PITA accounting for the currency

Not generally one for currency bets but Powell yesterday, Bailey today and the UK’s apparent proclivity for self flagellation has me looking to up the USD exposure in my portfolio a bit notwithstanding the ‘GBP’s down a lot and might go back up’ analysis

Thanks if anyone has any thoughts

Oh god, now I’ve read the explanation I’m embarrassed ! Thanks. For some reason I had in mind bonds were bought and sold as a whole rather than fractionally, thanks again.

@A Reader: You could cover the spectrum with US bonds as it’s the largest, most liquid bond market in the world. A mix of very short TIPS and long Treasuries gives a triple rebalancing bonus between £ and $, inflation linked and not, and long and short durations. This can be achieved with a mix of TP05, TI5G, IBTL and IDTG. I hold only TI5G and IDTG cos I am expecting the £ to recover eventually, but it seems to me that holding all four is a less active arrangement.

@Onedrew

Very helpful thank you, much appreciated

Please could anyone provide some examples of ETFs that cover these gilts?:

Intermediate global government bonds (GBP hedged)

Short global index-linked bonds (GBP hedged)

Cash and/or short government bonds (Gilts)

Thanks!

Intermediates

https://monevator.com/best-bond-funds/

The others:

https://monevator.com/low-cost-index-trackers/

also see the names of the ETFs used in the charts in this piece

Great article! When I was running 60/40 I bought gilts instead of using a fund. The ladder spanned roughly 7 to 13 year maturities. Every year when we rebalanced I would sell the short dated gilt and usually just buy a longer dated gilt. This was very cheap to do as gilts have very narrow spreads and I was only turning over a fraction of the portfolio each year. It was at times complicated though and now that bond funds/ETFs have such low charges I would hold them instead.

I would echo @snowman’s comments about cash, a much maligned asset class IMHO. You can almost always get better returns on term deposits than on short dated bonds. The last few weeks have been an exception, where you could get better returns on short dated gilts than on best buy deposits. I used the opportunity to buy gilts maturing in January 2024, 2025 and 2026. However, even in this case the gilts only give better returns AFTER TAX, not before tax. That is because the coupon on these gilts is very low at only 0.125%, 0.25% and 0.125% so most of the return comes as a capital gain, which for gilts is tax free. I have noticed though that better deposit rates have been appearing and the gilt yields falling, so it might be the case now that, for basic rate taxpayers at least, term deposits offer higher net returns again.

For “Decumulators – simple”, I would argue that FSCS protected cash deposits (or maybe short bonds where decent cash deposits are unavailable, such as in SIPPs) is likely to be the safest option. In my back tests using US and UK data I found that using intermediate/long bonds gave the best outcome on average and in the majority of scenarios, but there were a handful of cases where short dated bonds were better. However, these cases coincided with the worst case scenarios. Opting for short dated bonds in these worst case scenarios resulted in higher safe withdrawal rates than were obtained with intermediate/long bonds and gave a less uncomfortable ride (still very uncomfortable though). It boils down to a question of what a decumulator is looking for with their bonds. A likely better return, or a better outcome in very unlikely worst case scenarios. I prefer the latter.

Introducing short dated index link bonds is an interesting proposal, unfortunately though there is very limited historical data for these as government index linked bonds only started being issued in the 1980s, starting I think with UK linkers. TIPS date back only to 1997. So the arguments for index linked bonds is mostly theoretical. I note as well that even with the Lyxor short dated index linked bond fund, I would still have lost money this year, compared with a small positive return on cash.

@Snowman re #5 – You wouldn’t expect gilts (lending to the UK government which can print its own currency) to yield higher than bank deposits (lending to private corporates). The FSCS scheme is an implicit government guarantee which makes the savings yield lower than it should be, but still not equivalent to gilts.

@TI re #21 – The structure of gilt issuance is set by Government with advice from the DMO who then execute according to that remit. The below paper is a good overview. Note it was expected to be cheaper to issue index-linked vs nominal gilts in Jan-17 and pension funds were asking the DMO to issue more, however the amount was capped at ~25% to reduce inflation exposure.

The UK already has significantly longer term to maturity (~18 years) vs the OECD average of (~8 years). Chile is next longest at ~11 years. See figure 1.14 in the OECD pack.

https://www.dmo.gov.uk/media/iybgp5t1/annexb_debt-management_report_2017-18.pdf

https://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/public-debt/Sovereign-Borrowing-Outlook-in-OECD-Countries-2021.pdf

@Reader:

I have IBTS for short USTs, plus TP05 and ITPS.

All trading in GBP to avoid Fx fees. (Or you could go to IB who charge almost nothing.)

All un-hedged because I *want* to diversify away from the Great British Peso.

Much credit to Monevator for pointing out the flaws with UK linkers years ago.

@The Accumulator

You said earlier in relation to savings rates vs gilt yields ‘knowing you, you’re bound to have spreadsheeted this!’

Well I had to admit earlier that I hadn’t, but a poster on MSE called Ocelot has been keeping a record of best buy fixed rate savings accounts since the end of 2018 and posted the data up today

So that has now enabled me to compare the 3 and 5 year gilt historical redemption yields from the Bank of England website (spot rates actually) with best buy savings accounts (ISA and non-ISA) at the same time points.

Here’s the resulting chart from the spreadsheet.

https://ibb.co/zHDGqh5

Hi everyone. So, I think (thanks to super posts like this) that I now properly understand how bond funds work and how changes to interest rates impact their value (should you sell them), and how different types of bond funds (short, intermediate, long etc) all contribute to the whole risk vs return equation.

I also understand that when you get into decumulation mode that bonds are a reasonable asset class for smoothing out the risk of crashing “killing your pot” as they are usually less volatile than shares.

So, my question is this… As I understand it, there are still risks of price fluctuations when buying and selling bond funds (as they contain many, many bonds – all maturing at different times – as we saw in 2022). So is another reasonable strategy to look at buying individual bonds, that mature specifically when you need them – so you have no need to sell them – (potentially at a loss) – you hold to maturity? E.g. if you have a retirement time horizon of 40 years, would it be a reasonable option to have 10 individual bonds (specific UK gilts not funds), each maturing one year after the previous, providing the income you expect to need in that year… With the rest of the pension pot invested in stocks and shares for years 11 to 40.

I am thinking that with this approach there is no risk of interest rate fluctuation negatively impacting the price (as it does with a bond fund) at the time you need it. UK Gilt rates are currently about 4% YTM, and interest rate forecasts seem to be averaging around 3% over that period (so real return of 1% if that plays out – which of course it may not I guess)?

Is there anything inherently wrong with this approach? Or are there other factors I am not considering (for someone of 56 who is keen to offset sequence of returns risks – at the expense of sacralising potential growth / loss in that “early years” part of the portfolio).

Brilliant article as always! Keep up the good work!

Roy

@Roy — I’m out and about on my phone right now so have to be quick, but have you read our posts about index-linked gilt ladders? Eg.:

https://monevator.com/should-you-build-an-index-linked-gilt-ladder/

https://monevator.com/index-linked-gilt-ladder/

(Please note: never personal advice as to what exactly you should do here, just food for thought/further reading! 🙂 )