The 4% rule does not work as advertised. Where does that leave folk with dreams of retiring one day? What’s a better number for UK and global investors who need a SWR that survives contact with reality?

The big benefit of the 4% rule is that it’s inspired some brilliant research. You can use this research to find your baseline SWR and calculate a reasonable retirement target figure. If you’re retired or near retirement, that baseline SWR offers you a simple formula for drawing down your nest egg at a prudent rate.

So a realistic SWR is worth having. We just need to know where to look for it.

The World portfolio SWR baseline

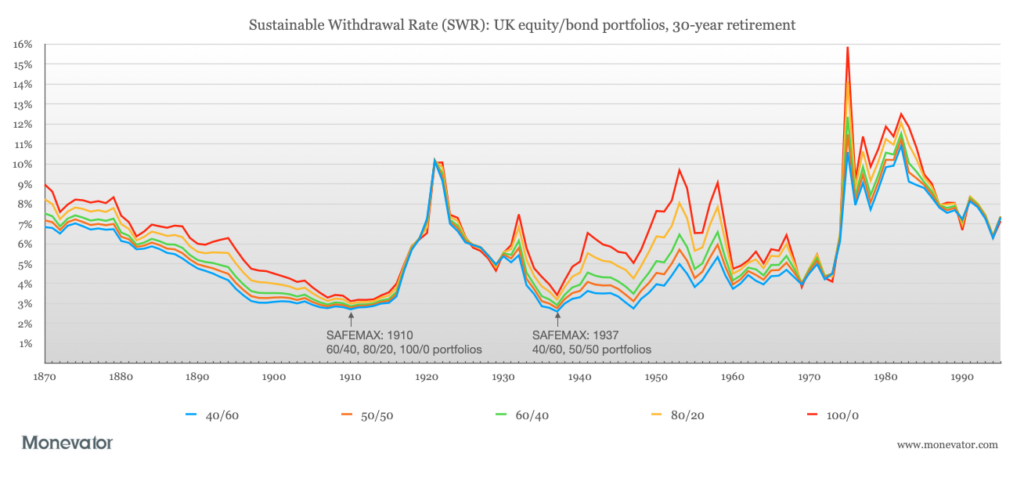

Wade Pfau is a leading researcher on international withdrawal rates. He used historical returns from 1900 – 2015 to calculate a SWR of:

- 3.45% for a Developed World portfolio (50:50 world equities / world bonds)

- 3.36% for a UK portfolio (50:50 UK equities / UK bonds)

This theoretically means that you could withdraw an inflation adjusted 3.45% from your Developed World portfolio annually – without running out of money – throughout a 30-year retirement, no matter when you retired from 1900 to 1986.

Note I say ‘theoretically’. In the real world the SWR shrinks before the headwinds we’ll discuss below.

We’ll use the Developed World portfolio SWR from here on in. It best tallies with the diversified Total World portfolio we think makes most sense for UK investors.

Failure rate bonus

It’s not often we’re rewarded for failure but our SWR goes up to 3.93% if we’re prepared to accept a 10% failure rate, according to Pfau.

Failure means our money would have run out before our 30 years was up in 10% of all historical scenarios. I think this is an acceptable failure rate because:

- A conservative SWR strategy leaves lots of money on the table in the majority of scenarios.

- People can avoid running out of money by cutting back their withdrawals when they see their portfolio drying up.

- The 10% failure rate is reduced by the cheery chances of you dying before your nest egg dwindles. (Jump to our article on investor maths and scroll down to the Probability: Will you need all that money? calculation for more.)

Okay, so a 3.93% SWR it is. How much do we need to retire on then?

1 / 3.93 x 100 = 25.45 times our annual retirement income need.

For instance, if you needed £25,000 income in retirement:

25.45 x £25,000 = £636,250

Editor: You clutz! It’s the 3.93% rule then? In short, the 4% rule does work, you total time-waster?

No!

Much like Monty Python’s Black Knight, our SWR is about to get chopped down to size.

Or maybe eaten is a more appropriate analogy…

SWR layer cake

Your personal SWR depends on ingredients such as:

- Investment fees

- Taxes

- Length of retirement

- Asset allocation

- Sequence of returns

- And more

These factors vary by person and help explain why the 4% rule is one size that fits no-one.

To narrow the uncertainty William Bengen (the father of the 4% rule) proposed the withdrawal plan layer cake.

The layer cake customises your SWR by adding bonuses and penalties for various factors that may influence your retirement outcome. The concept was expanded by Michael Kitces, the renowned financial planner and retirement researcher. It’s Kitces framework we’ll use to hone our baseline SWR.

Be aware that the layer cake is a confection standing on a pedestal of assumptions.

As Kitces says:

Although the ‘layer cake’ approach of safe withdrawal rates does allow for planners to adapt a safe withdrawal rate to a client’s specific circumstances, there are several important caveats to be aware of.

The first and most significant is that many of the factors discussed here were evaluated in separate research studies, and it is not necessarily clear whether they are precisely additive.

Ongoing SWR research certainly implies that your specific cake mix will raise or lower the profile of individual ingredients.

For instance, Early Retirement Now (ERN) has shown that higher equity allocations have historically enabled higher SWRs over long retirement lengths.

Note: Double beware: the layer cake is baked with US data. The assumptions may not hold to the same degree using international datasets.

TL;DR – the layer cake approach is art as much as science, but it is more sophisticated than the naive 4% rule.

Let’s bake our SWR cake.

Deduct fees

Our SWR is nibbled away by investment fees. Fund fees, platform fees, advisor fees – in short any percentage slice of your returns that you don’t account for in your annual income requirement.

Happily, your portfolio’s percentage fees aren’t just chipped straight off your SWR. There’s good evidence that the loss isn’t that bad. 1

Multiply your total expenses by 50% instead.

For example:

0.5% (my total fees) x 0.5 = 0.25% SWR deduction.

The Accumulator’s layer cake SWR:

3.93% – 0.25% fees = 3.68%

Retirement length

This one is a biggie. So far we’ve assumed that we’re willing to cark it within 30 years of retiring. But what if you’re not feeling so co-operative?

The quicker you clear off, the higher your SWR can be. Plan on hanging around? You incur a SWR penalty for loitering.

Blogger ERN uses US data to show that SWRs gradually decline as retirement stretches from 40 to 60 years. The SWR tends to level out at some point along the curve, especially if your SWR is conservative.

I haven’t found publicly available global historical data for retirements over 30 years, so let’s apply Kitces’ time horizon modifier:

- +1% SWR for a 20-year time horizon.

- +0.5% SWR for a 25-year time horizon.

- -0.5% SWR for 40 years or more.

Intriguingly, Kitces’ modifier tallies with the results published by Morningstar in a research paper: Safe Withdrawal Rates for Retirees in the United Kingdom.

Morningstar employs a proprietary formula to estimate future SWRs for UK retirees, assuming a diversified portfolio tilted towards UK securities.

The Morningstar results suggest:

- +1% to +1.3% SWR for retirement lengths ranging from 20 to 25 years (depending on equities allocation and failure rate)

- -0.4% to -0.6% SWR for retirement lengths ranging from 35 to 40 years (depending on equities allocation and failure rate of 10%)

I’d like a long and happy retirement, please: I’ll take the -0.5% hit on 40 years plus.

The Accumulator’s layer cake SWR:

SWR 3.68% – 0.5% retirement length = 3.18%

Taxes. Uh-oh

You can’t avoid death and taxes they say (though watch me try!) and both must loom large in our SWR calculations.

The baseline SWR does predict your death. But not your tax rate because that’s a lot of work.

The simplest thing to do is to estimate the annual, gross, pre-tax income you will need.

For example, say you need £25,000 to live on. You believe it will all come from taxable sources, such as your SIPP and State Pension, but remember that everyone has a personal tax-free income allowance:

£25,000 – £12,500 tax-free personal allowance = £12,500 (the portion taxed at 20%)

£12,500 / 0.8 = £15,625 (the gross income you need to meet your after-tax income target)

£12,500 + £15,625 = £28,125 (the total gross income you need to live on £25,000 a year)

£28,125 / 3.18% SWR = £884,433 (target wealth required to retire and pay your taxes)

If instead you intended to draw down £12,500 of your £25,000 from ISAs then you wouldn’t have any more tax to pay on this sum.

That would make your target…

£12,500 / 3.18% = £393,081

…in your ISAs and the same again in your SIPP.

Think tax rates will be different in the far future? You’re right. Feel free to input whatever tax schedule you prophesise.

The Accumulator’s layer cake SWR:

3.18% (with taxes accounted for by gross income estimate)

Leave a legacy

Want to leave something for the kids? Then you’ll need to lower your SWR. The baseline case assumes you’re prepared to spend your last penny.

With that said, Kitces has also shown the baseline normally produces a large legacy in most 30-year historical scenarios. You only check out with less than your starting capital in 10% of cases (again, US data).

If you want to improve your chances of leaving 100% of your nominal capital then Bengen and Kitces suggest cutting your SWR by 0.2%. Increase the penalty for more glorious legacies.

I don’t have kids, so…

The Accumulator’s layer cake SWR:

3.18% – 0% legacy = 3.18%

Market valuations

Since the global financial crisis of 2008/9, bond yields have collapsed and equity prices soared. Many commentators suggest we now live in a low growth world with weaker expected returns relative to historical norms.

Wade Pfau warns that lower bond yields diminish the chances of the 4% rule working for US portfolios with 50% bond allocations.

Worse still, ERN has shown that high US equity valuations bring down the SWR over long time horizons. Toppy valuations increase your chance of running into an adverse sequence of returns – the risk that near and early retirees are especially vulnerable to.

The good news is the rest of the world does not look as expensive as the US today by the light of the CAPE ratio – a widely used measure of stock market value.

- The US CAPE ratio is over 30 versus its historical average of 16 – pricey!

- World CAPE is 23 versus an average of 20. A little high but not too rich.

- UK CAPE is 16 – right around average.

That suggests high equity valuations are less worrisome to globally diversified investors than to home-biased American investors hoping their stellar run continues.

The World SWR already incorporates losses far beyond the worst suffered in the US. The World dataset includes the hyperinflation and physical destruction of two World Wars that laid waste to the Japanese, German, Italian, Austrian and French markets among others.

This should all (hopefully) mean the World SWR can cope with a wider range of nightmare scenarios than a US SWR buoyed by the bounty of the American Century.

Kitces’ valuation recommendation is:

- +0.5% SWR for an average valuation environment

- +1 SWR for a low valuation environment

Kitces also says:

Consider reducing the safe withdrawal rate in extreme combinations of high valuation and low interest rate environments.

Certainly Developed World bond yields are low. But equity markets don’t seem overcooked on aggregate. I’m going to play it cautiously and round down my SWR to 3% due to the low interest bond situation.

The Accumulator’s layer cake SWR:

3.18% – 0.18% valuations = 3%

At last! My world portfolio SWR

I’ve battered my personal SWR with every negative factor going and ended up with an SWR of 3%.

My desired income in retirement is £25,000, so my retirement target at 3% SWR is:

1 / 3 x 100 = 33.3333 x £25,000 = £833,333

But the story doesn’t end there! We can add another set of tiers to our layer cake to make our SWR rise again. Like blowtorching an edible Paul Hollywood on Bake Off, these moves require upgrading your skills – read about improving your SWR here.

If you want to keep things simple and just apply your SWR at a constant inflation-adjusted rate to produce a predictable retirement income, then the steps above can put you on a sounder footing than naively following the 4% rule.

The important thing is to be conservative with your assumptions, understand how SWRs work and have a back-up plan.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

- From the link: “The explanation for this is that, under the SWR framework, income withdrawal is adjusted for inflation, which means the income goes up over time and as the account balance is depleted over time, the impact of %-based fee is reduced.”[↩]

Comments on this entry are closed.

Really nice post and analysis, many thanks. I guess you’re being conservative here as you’re thinking that you will receive no benefit from the state pension in later years which would reduce your lump sum requirements.

What is likely to prevent me from being able to FIRE is the fact that majority of my assets will be in pensions and ring-fenced until I’m (at least) 55. Do you have an article about how to manage that process and how to allocate savings?

Why would you want to adopt a strategy that might well leave you with a mountain of money when you are too old or decrepit to enjoy it, and have no grandchildren to leave it to?

Here’s a more rational approach which might be adapted to work well in Britain even though the design was intended to exploit an idiosyncratic feature of the US pension rules.

I invite you to calculate what the approach would imply for you.

http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/IB_12-19-508.pdf

If the SWR means you draw an income without touching your principle then why does it matter how long your retirement is because if you select a suitable SWR then at the end of 30 years you’ll still have the original principle which is continuing to earn?

@Conor, SWR is not about not touching capital, its a drawdown strategy that ensures you don’t run out of money after a set time. The capital growth of equity markets above inflation allows you to spend some of your capital and keep the initial sum index linked to inflation, but a pure live-off-the-dividends approach will require a much larger initial pot

“If you want to keep things simple and just apply your SWR at a constant inflation-adjusted rate to produce a predictable retirement income, then the steps above can put you on a sounder footing than naively following the 4% rule.”

Hmm, a fixed percentage SWR does not provide a predictable income from a largely equity based portfolio, where prices can change +/-40% in a year (mitigated a bit, but not eliminated by any bond/fixed interest holdings)

@Kraggash – You select your initial SWR percentage in Year 1 and just adjust for inflation each year. If your Safe Withdrawal Rate is, well, safe, your money will outlast you. If your money falls 40%, you still adjust for inflation and carry on.

@Brod – that I understand. But getting e.g. £50k one year and £30k the next is not what I would call a ‘predictable income’.

A prolonged bear market, think of Japan, can be devastating for a retiree using SWR rates. It produces a scarcity mindset when your depleting capital each year and your drawing income to live off. I much prefer a cash flow model of dividend growth stocks and direct ownership of rental real estate which results in an abundance mindset and its much simpler to understand, you only spend what income your assets throw off. I know it takes a larger capital base but your truly FI when your cash flow producing equity is generating income > expenses. Regards, Jon

I prefer to consider the actual natural dividend yield of my portfolio rather than a theoretical “safe withdrawal rate”. If you’re prepared to invest in investment trusts in the UK equity and bond income, property direct UK, Asia Pacific excluding Japan (income), global equity income, and UK equity income sectors then yields of 6.0%, 5.0%, 4.8%, 4.0%, 3.9% are attainable (Source: http://www.theaic.co.uk at 08/04/2019). Based on these yields you don’t need more capital to follow this approach, but you do need to focus on investments that generate a growing income.

@TA. If you want a 3% yield from a global portfolio then a 60/40 split between the global equity income and global investment trust sectors would currently deliver that with yields of 4.0% and 1.6%.

@minted this might explain why many people are not keen on the ‘dividend yield’ approach to designing a portfolio

http://www.theretirementcafe.com/2019/04/a-good-many-retirees-seem-to-be.html

@Vanguardfan – yes that confirms my thoughts.

Plus, people in search of dividend often select high dividend funds/stocks, (rather than the natural yield from e.g. a index tracker) which is then only a subset of the whole market. (A subset with a lower total return, in my experience).

@Kraggash, you won’t get £50k then £30k. If the initial SWR gives £50k in year 1, then if inflation is running at 2%, in year 2 you drawdown £51,000.

@Vanguardfan. I don’t agree with Retirement Café’s negative view on a spend the dividends only approach. I left comment #67 on the earlier article (https://monevator.com/why-the-4-rule-doesnt-work/).

@Kraggash. I agree that you are selecting from a subset of the world market. I believe my chosen subset can match or beat the FTSE All Share index but not the global index at present. For the last five years (to 31 December 2018) I have compound growth of 4.68% per annum compared to 4.07% for the FTSE All Share index.

@minted. I would say that five years experience of one portfolio is insufficient evidence to make a general conclusion. Have you looked at what happened to dividend income during the financial crash? What is your strategy if your dividend income falls substantially?

I thought the article made a number of thoughtful points quite well. I don’t think it’s saying a ‘live off the dividends’ strategy is ‘wrong’, but that the main benefit may be psychological, and that there are some common misconceptions. If you are happy with your approach, that’s fine.

@vanguard, Dividend Aristocrats are stocks with 25 years of increasing dividends, Dividend kings are stocks with 50 years of increasing dividends. Dividend income is fairly stable if your diversified across 30-60 high quality stocks. However the future is unknowable and I feel Dividend stocks should only be one element in your overall strategy. Real Estate is a good diversifier.

@W Neil – I am talking about when an equity portfolio drops in market value, and you are using a fixed % SWR. Your £ annual income will drop as well.

Nothing to do with inflation.

@Kraggesh,

I was referring to your reply to @Brod who replied to you “@Kraggash – You select your initial SWR percentage in Year 1 and just adjust for inflation each year.” You: @Brod – that I understand. But getting e.g. £50k one year and £30k the next is not what I would call a ‘predictable income’.”

The point is you would still withdraw £50K +/- inflation regardless. Your first post quoted TA about inflation adjusted SWR but your comment for some reason referred to a fixed percentage SWR. I don’t think anyone on here is suggesting anything based on withdrawing a fixed percentage of your portfolio every year, are they?

I’ve always found the SWR rather low, I mean you could put your money under the mattress and withdraw 3% for 33 years, ok your not taking into account inflation

@ Kraggash – the phrase ‘constant inflation-adjusted income’ refers to the practice of taking the same income amount from your portfolio year-in-year out. It’s very purpose and attraction is that it provides a predictable income. An SWR strategy attempts to square the circle of withdrawing a constant income from a volatile portfolio by setting withdrawals at the minimum amount that history says would investors could have sustained over X years of retirement. You seem to be referring to variant strategies that do allow income to fluctuate. A fixed % withdrawal strategy as mentioned by W Neil is one such variant.

Re: dividend strategies. ERN has written several pieces on the challenges of a dividend strategy: https://earlyretirementnow.com/2019/02/13/yield-illusion-swr-series-part-29/

A dividend strategy really means you withdraw from your portfolio using a lower SWR. Lower is safer than higher, but it’s also more expensive i.e. you need a higher capital base to maintain a given level of income. If you think you can just withdraw at a higher rate because you can tap into ‘dividend aristocrats’ etc, well, then you’re hoping for something for nothing. Pain-free trade-offs are as rare as unicorns in investing. If you accept that dividends aren’t free – and many excellent researchers and commentators have gone to great lengths to show this to be the case – then taking 5% income from high dividend payers just means you’re drawing down at a higher rate than a total return investor selling 3% of their portfolio.

In my opinion, this is one of those areas of financial independence where your head risks exploding unless you’re careful.

And where trying to land on an SWR that’s more precise than one that you’ve rounded down (to be conservative) to, say, the nearest 0.5% is most likely claiming a false level of accuracy. And even that one’s only a guide, if you’re having to think more than 30 years ahead.

Using this more high-level approach, my wife and I concluded that 3% is the SWR that will guide our financial goals – significantly more conservative than using 4%, whilst 2.5% was too close to the yield on the world market portfolio.

And there’s a beauty in the simplicity that comes from using 3% (I can do most of the calculations in my head) that’s not to be undervalued.

@Accumulator – ok, I seem to have misunderstood.

But you can perhaps see that wording like “.. you could withdraw an inflation adjusted 3.45% from your Developed World portfolio annually…” (Your phrase) could mislead.

@Kraggesh. One of the problem of SWRs based approaches is that they clearly can’t be optimal. Take two people each have an identical £1mm portfolio at the beginning of the year. Person 1 retired at 50 and decides to follow the 4% rule and withdraws £40k that year. Person 2 retired say 5 years earlier at 45 when their portfolio was at £1.25mm (inflation-adjusted) but through withdrawals/negative returns, the portfolio is now £1mm. Based on the same SWR their withdrawal is still £50k. Despite having the exactly the same portfolio value, same age, person 1 and person 2 are withdrawing different amounts. They cannot both be acting optimally given they have the same boundary conditions.

SWR approaches (and those approaches derived from it such as Guyton-Klinger, harvesting etc) all have this time inconsistency problem. They all violate the principle of optimality (Bellman equation). If you are being nice, SWR is a historically stress tested solution. If you are being mean, it’s just data mining! But either way, it’s actually a very practical approach.

By constrast approaches such as using a constant percentage rate (so variable income), VPW, or valuation approaches (say using some CAPE yield, real bond yield etc) have the advantage they do satisfy the Bellman equation. They are optimal since at any point in time, all individuals with the same position would withdraw the same percentage that year. The problem is that they are not really practical. It’s incredibly hard to vary your spending, potentially by substantial amounts, each year just because the market goes up or down.

@dearieme thanks for highlighting the Sun and Webb article – very interesting and I’d encourage others to read it. I’ve not yet seen their full article but will try and get hold of it though is suspect it will be behind an academic subscription paywall. The modified RMD drawdown method is especially intriguing and only has a 3% penalty (i.e. increased initial required assets) against optimality compared to up to 49% in the case of other SWR rules considered, but allows for greater initial withdrawals by spending interest and dividends plus RMD drawdown. In the case illustrated by the authors of a couple with a £102,00 portfolio on retiremnt this meant a $5,130 permitted drawdown in year 1 vs $3,130, a substantial difference.

@ZXSpectrum48k Thanks for noting the ‘time inconsistency problem’; your example of how the problem arises I found very helpful.

Personally I’ve been ‘in drawdown’ for a couple of years now, and so far I have got by with taking an overview of several drawdown estimates to get an idea of the upper and lower bounds for an annual withdrawal. I keep drawdown towards the lower limits I find, but would not be overly concerned if I needed to drawdown up to the upper end of the range say 1 year out of 4. The lower end of the range I find is based on an actuarial approach (explained here: http://howmuchcaniaffordtospendinretirement.blogspot.co.uk/) requiring estimates of forecasting future expenditure (including long term health and bequest motivations), portfolio returns, inflation etc. and this works out at 3.75% drawdown, though I worry I am a bit optimistic about the 5.75% real growth estimate I use. The upper end of the range for my case is the McClung harvesting strategy which currently produces an estimate of 5%. A big chunk of my income though is an index linked pension and I think if I had a large investable fund and no pension base I would certainly consider replicating it with an annuity for peace of mind – even at the current rates (https://www.hl.co.uk/retirement/annuities/best-buy-rates), which provide 5.3% for single life cover (not index linked) at age 65. I’d take that and plan on saving at least 1% (i.e. 20% of the 5%, if you see what I mean!).

I’m not so sure its difficult to vary your spending if you are living the good life. You can postpone capital costs like new cars, patios or roofs to good years, switch from exotic holidays to UK based ones, play with the toys/books you’ve got rather than acquire new ones. Its much harder if you are close to the limit of course. While there is lots of research on market returns, I wish there was more social survey data on actual retirement spending.

Unless I’m mistaken in the taxes calculation above the impact of the PCLS isn’t included? Seems like it should be as this will significantly reduce the gross income required to meet the target income and therefore increase the SWR…

When did index funds arrive on the investment landscape? 70s? before then, the cost to invest was higher, surely? can TA not add back in a few basis points now that todays investement costs are much lower ? why has he not taken this into consideration?

@Dawn — He’s discussing ways to increase the SWR in the next part, as mentioned at the end. With that said the 4% rule research was from the early 1990s from memory.

@ZSX +1. The whole idea that you could be 15 years into retirement and still executing a plan you made 15 years ago without attending to what happened since is bizarre to my thinking. So I reckon SWR is ok to get a feel for what may be a sound approach now, but makes no sense if applied as a baked in plan. Annuities are based on models of returns and life expectancies. I don’t see how, as individuals, we can beat that in aggregate if we adopt the same rules. Some will win – spend high die young- others will loose: spend low die young, spend high and run dry. If the SWR guided return drifts away from annuities then something has shifted and I reckon that’s risk. So out of a possible 100 lifetime trajectories from here, perhaps 90 are successful and 10 crash. Which lifetime am I actually going to get. 9 make me look a genius, 1 makes me claim to be unlucky. Same smart thinking applied to them all :).

@ Adam B – the tax example was just an example. The idea was to show how you can incorporate your tax situation into the calculation. The 25% tax-free lump sum just gets folded in to your personal circumstances.

@ Dearieme – do you use the RMD system? If so, how do you manage the income volatility implied in the system? How does the system work if you want to retire before 65.

@ Dawn – the baseline SWR comes from historical prices that don’t include investment costs. So the higher costs that would have actually burdened investors are factored out already. You won’t need to deduct much if you’re investing in cheap index funds but it’s still a cost not a bonus.

I don’t buy that you neccessarily need a bigger pot stashed to support a natural yield approach. It depends what you’re invested in. And I wouldn’t expect to take much income if you’ve got 50% of your pot in UK gilts paying 1% (especially when inflation is double or triple that).

I’ve managed a net 4.25% yield over the last tax year after all fees and charges, based on current pot valuation.

We’ve had a good start to the year so the average yield over the last 12 months is higher than that. The real test will of course be how yield is impacted in a bear market.

But not all companies cut their dividends in slumps, as evidenced that the yield on major equity indices typically rises in a bear market.

Added to which anyone following this natural yield approach should – in addition to equities – probably have exposure to REITs, infrastructure, various types of bonds (EM, corp, etc) that have more stable yields and are less prone to being cut.

Jon and Getting Minted seem of similar minds on this to me.

For someone who’s income (nearly) entirely goes on basic needs, the possibility of failure under a swr is unacceptable and an annuity is the appropriate solution.

For those of us with large discretionary spend, we’re happy to adjust spending and roll with the punches (@zxspectrum48k the “pain” of adjusting spending rate is the reason persons 1 & 2 should have different rates in the swr framework).

Therefore I don’t think the swr approach is appropriate for anyone (although it gives a ballpark). If one wants to get a really good plan, simulation is the only way. Ever more fiddling with the swr won’t get you there.

@Semipassive. I was taking my cue from here:

http://www.theretirementcafe.com

‘But, if you plan to spend down retirement savings with a strategy based on preferring a dollar of dividends to a dollar of capital gains, you are betting against economic theory, portfolio theory, historical evidence, tax law, behavioral finance and the wisdom of Warren Buffett.

Then again, maybe you will be lucky.’

And

‘A recent series of three posts at the EarlyRetirementNow blog entitled “The Yield Illusion: How Can a High-Dividend Portfolio Exacerbate Sequence Risk?,”[3] shows that a high dividend yielding portfolio doesn’t mitigate sequence risk and can, in fact, exacerbate it.’

Thanks Dirk, hope you don’t mind.

@ SemiPassive – how do you counter the arguments of credible commentators who think there is no advantage to a high yield approach? If you invest in higher return assets then do you accept you’re taking on higher risk? How and when does this show up? High dividend assets are not a source of outsized returns according to the financial academics who discovered factor investing in the shape of value stocks, small cap stocks, quality and so on. The high yield bonds you listed… they are prone to default i.e. your yield gets cut, particularly during downturns.

@ Ben – what do you mean by simulation? Also, by SWR approach do you mean the 4% rule? Barring world war scale / hyperinflation disaster I think 3% and below is pretty safe. If you have the chops to bring some of the more sophisticated techniques into play then 3%+ will leave you in the black most of the time. I agree that many will benefit from an annuity come the day (although only an expensive escalating annuity has inflation protection), but few of us will need to rely solely on any strategy as eventually the State Pension comes along. Ultimately I want to have as many tools in the box as possible: a good drawdown strategy based on techniques devised by the best retirement researchers, knowledge of when to annuitise (and not to irrationally dismiss this as a strategy), and understanding of my options should I ever need to tap the house as an asset.

TA, I’ve never claimed a high yield approach outperforms the market as a whole. I don’t even care if it underperforms given the advantages I’ve already blathered on about on here before. Simplicity being a key one.

Re: “If you invest in higher return assets then do you accept you’re taking on higher risk?” – Yes, totally. Aware there is no free lunch.

Also when discussing risk, I’m sure you are aware of the difference between short to medium term volatility vs the longer term risk of assets failing to keeping up with inflation or provide an adequate return. If you are holding assets forever (and just taking the natural yield) then volatility is not a problem.

On EM govt bonds, only a few weeks ago this blog linked to an article regarding long term performance stacking up very favourably against equities, only with less volatility.

And spotted this one yesterday:

https://moneyweek.com/504960/it-makes-sense-to-lend-to-governments/

Of course they are riskier than US treasuries, I’m not disputing that.

For interest I’ve split my allocation to this area between a couple of iShares ETFs, tickers SEML and EMHG.

As usual don’t put all your eggs in one basket, while skewed to a higher yield approach I still hold ETFs linked to general indices that hold growth stocks and have a separate pot with safer assets like short dated gilts and other GBP bonds, and cash.

I am tracking progress and it will be interesting to see how my income portfolio fairs against the market as a whole (maybe comparing against VWRL) over the next 5 to 10 years.

I certainly don’t expect VWRL to be as good over the next 10 as it was over the previous decade. I do expect my portfolio yields to at least be more predictable, so I have a more realistic idea of that component of my total returns. But who knows?

I hope that helps explain my point of view.

Hi TA, constant real withdrawal (swr) assumes adjustment aversion of 100% (you’d rather withdraw your last £ and hope for death in 12 months than adjust). Being more realistic means replacing this assumption with subjective info like a utility function, death probability function etc. Withdrawal strategies can then be compared by stepping through time, withdrawing your spend and making a return. If the returns are drawn from a real sequence (a la pfau), you get limited repeats but using bootstrapping or an RNG you can simulate as many observations as you like.

I’d suggest a strategy with floored percentage withdrawals where the percentage increases with age (not wanting a legacy means there’s little point withdrawing only 3% of funds when you’re 80).

@SemiPassive – Thanks for clarifying. Your comment: “I don’t buy that you necessarily need a bigger pot stashed to support a natural yield approach. It depends what you’re invested in.”

I interpreted that as you saying an investor could withdraw at a higher rate from their portfolio than allowed for by a total return approach, if they stuck to natural yield, and invested in high yield stocks.

I think the risk that entails is the natural yield investor may need to cut income later, perhaps because dividends are cut / defaults rise / portfolio underperforms. You can’t run out of money with a natural yield approach but volatility is still a problem, except it’s income volatility.

I see that there’s more to your approach than ‘dividend investing’ but I’m debating it because often the natural yield approach is talked about like it’s a ‘get out of jail free card’.

Re: EM bonds / high yield corporates – they may have a place in a portfolio (though not mine) but I was trying to say that their default rates rise at the very time you might hope for diversification benefits in a portfolio – during recession, when equities are under pressure too.

@ Ben – your strategy very much tallies with McClung’s approach. Does RNG mean Random Number Generator? What tools do you use to run your simulations?

A short, readable post that highlights some of the shortcomings of dividend investing:

https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/5-reasons-to-avoid-focusing-on-dividend-stocks/

for a start the 50/50 allocation is not the most optimum to test the 4% rule – 75/25 in favour i believe is – so 50/50 @ 3.94% would mean 75/25 would be higher than 4%

the 4% rule with flexibility is needed and anyone who has studied the 4% rule I do not believe is dumb enough to just forget about their portfolio balance for 30 years and hope.

I also feel that inflation increases are a bit OTT coinsidering most people in the UK have had no pay rises until recently on average… they lived with that for 10 years whilst working… how hard would it be to go through a decade of no inflation increases in retirement? not too hard considering most have gone through it whilst working.

the average UK equities return is over 6% – I really struggle to see such fear around 4% – it is just fear based and people in the UK are overly negative about pretty much everything for some odd reason

@Jamese20 Ten years when inflation has been at historic lows. If inflation rises to a higher rate (possible with the fall in the pound) you may struggle.

@ kraggash

3 years lower the average alot but many of those years had over 2% inflation…… and dont assume I mean never giving yourself inflation rises… but you could have had 10 years of not doing it the last decade and been fine, meaning more growth in your account and a more secure retirement without feeling like you are much poorer.

You make reference to the first Morningstar research paper but not the more recent one ( October 2017). This suggests a SWR of only 1.9 % for a 40 year timespan with a 60/40 equity/ bond split. It’s not clear from the research but it may assume 1% on fees which is perhaps OTT.

Yes, that paper is here:

http://media.morningstar.com/uk/MEDIA/Comprehensive_update_on_the_Safe_Withdrawal_Rate.pdf

It’s not clear and is certainly one of the most pessimistic outlooks you can find. This paper’s assumptions about future expected returns suggest that your asset allocation is irrelevant. The SWR ranges from 1.8% to 1.9% (40 year retirement, 90% success rate) whether you choose a 0% to 100% equity asset allocation.

If this paper’s projections came to pass I’d be pulling every lever possible to make it: dynamic withdrawal and asset allocation, part-time income, State Pension, perhaps some equity release, dying early 😉

Great articles as always. Thanks. I would argue that the vast majority of retirees spend much less as they get older. The only areas of expenditure that must be inflation proofed are bills, fuel, and food. Most people slow down as they get much older. Perhaps more on heating and less on eating. How many 80 year olds do you know are spending more now than they did at 60? The fly in the ointment is if long term care becomes an issue. So I think it is a little unreasonable to think that all our income must perpetually increase in line with inflation. Spending less as we get older increases the chances of any of the SWR being sustainable. Low cost gobal trackers, and high equity content will also go some way to helping.

Thanks, Mike! There’s a good deal of evidence in favour of a spending decline on average but individual experience can differ – with the lottery of healthcare (including social care as you suggest) holding the key to the puzzle.

To my mind, that makes this question a test of risk tolerance. Do you spend more now on the assumption your spending will naturally decline later? Or do you keep money in the bank *in case* you’re one of the unlucky ones?

Even in the short time I’ve been retired, inflation has exceeded all expectations and the NHS has unravelled to a shocking degree over the past few years. No plan survives contact with the enemy as they say…

Here’s a couple of Monevator posts that collate the retiree spending decline evidence and discuss the issues:

https://monevator.com/spending-decline-in-retirement/

https://monevator.com/spend-less-as-you-age/

Hi, I recently found your site and these articles are gold dust to me. With a UK perspective (as opposed to USA), it is just great to read and learn…

So, one thing I am struggling with related to SWR… I am looking to retire early (56) and planning using a 40 year timespan for me and the Mrs. I know my income needs annually (these will adjust at different stages of retirement), so I am trying to work out (based on a conservative SWR) how large a pot I need to make it happen. The issue I have is that my income needs are not the same for every stage of my retirement. In the early years (kids still about and no state pensions) I need more, lets say £50,000 pa. At the next stage (kids gone) I will need lets say £42,000, one state pension £31,000 and so on down to £20,000 or so for the final 15 years of the horizon. So if take £50,000 (the starting need) as the basis for my calc and use a conservative SWR (2.55%) it determines I need an enormous pot based on it thinking I need £50K a year for the entire 40 years (which I do not).

So my question is… how do I tackle the above issue of different annual needs at different stages? I have worked out (in todays terms) the average annual need over the entire time horizon (annual need each year in all 40 years divided by 40) to get an average annual income need of around £30,000 – do I just use that average as the basis of my SWR / pot size calc (bearing in mind that in no one year do I ever take out “the average”)? Or is there a better way to do it?

Thanks in advance, and again… compliments on the site… it is a fantastic resource!

@Roy — Welcome and glad you’re enjoying the site. While this doesn’t exactly answer your question, you may find the following two articles — and the comment threads beneath each — of interest:

https://monevator.com/spending-decline-in-retirement/

https://monevator.com/spend-less-as-you-age/

I’d caution that the SWR methodology is based on certain assumptions such as a particular investment return over a particular long timescale. Trying to chop and change it into chronological sections in advance in your planning is both being a bit ‘cute’ and liable to break something. 😉

With that said some do presume declining spending with age and so on, as discussed in the articles above. This is most likely to produce a higher SWR at the start — at a greater risk of running out of money. Remember your SWR later would still be high in this scenario because you would have spend relatively more of your pot, so you’ll need the higher SWR to keep your income coming at the desired level (and you probably best not hope for a Telegram from the King, depending on your exact circumstances haha).

Nobody here can give you personal advice, just food for thought.