When stock markets slump, people pay attention.

In some ways that’s a shame, because falling markets are as normal as rising markets.

Stock markets that go down faster than they went up are perfectly normal, too.

A stock market slump is therefore literally unremarkable.

But we’re human. We evolved to take an interest.

Our instincts run on fast-forward, even if our wiser slower brains try to press pause and ponder.

The price of admission

When markets fall, some panic and consider selling. That’s natural.

Others act brave, rub their hands, and boast about it being time to buy – to be greedy when others are fearful.

That sentiment is right, and they can sound like bold geniuses.

But how long were they sat in cash, waiting for the moment to get back in?

If you buy equities when they drop 10% but you missed the previous 50% rally, you’re not being greedy when others are fearful.

Not in the bigger picture.

You’re actually being timid when others are stoically betting on the long-term propensity of stock markets to rise over the long-term.

And you’re probably going to be left poorer compared to someone who is less cunning but more pragmatic.

The price they pay for their long-term gains is not feeling as smug as you when the market does swoon. They have to take their lumps.

Usually that’s a price worth paying.

Molehills and mountains

Investing is a marathon, not a sprint.

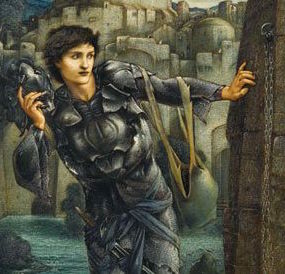

When markets fall you can feel like Indiana Jones, running down some corridor with the precious prize in your hand – but with a boulder thundering behind, threatening to squash you.

But that’s only one scene of the story.

A better movie metaphor might be The Lord of the Rings.

I’m thinking of that montage scene where three members of the Fellowship are shown galloping across at least three mountain ranges as part of their continent-spanning quest.

The heroes go up one peak, but right ahead of them is a march down the other side.

If the Fellowship had thrown in the towel at the bottom of one of those valleys then the ending would have been very different. 1

Investing is likewise – at best – a long march through peaks and troughs.

Hopefully you’re heading higher overall. But it’ll be a long time before you know for sure, and you need to be careful not to end up in a hole when your time runs out.

Otherwise it’s two steps forward, one step back – and repeat.

You knew this was coming

Fresh comments appear on old Monevator posts when markets fall.

- “I’m re-reading this post to remind me why I’m invested this way.”

- “I thought I was ready for a hit but I have to admit it hurts.”

- “This is my first real experience of falling off a cliff and to be honest…I feel alright really…”

It’s humbling to think we’ve built a site that people come to when they feel unnerved by investing.

It’s great too when another reader replies with some sensible words. That means we’ve built a community.

My co-blogger The Accumulator is always more alert to these sorts of emotional shifts than me.

He suggested I write a post reassuring readers about investing through tough times.

I suppose this is my attempt, but it might not be quite what he was expecting.

If you look around the Web you’ll find plenty of pundits saying this latest correction was overdue, or the slump is overblown, or that it’s a buying opportunity, or that in a year it’ll be forgotten.

Perhaps. Nobody knows. Not just in the short-term – we all understand such volatility around here – but also in the long-term.

We make our best guesses and we build diversified portfolios that can hopefully withstand those guesses being somewhat wrong.

But we never truly know.

All over in a flash

I’ve lived through a few of these stock market storms, and they can still surprise me.

Regular readers will know I’m an active investor for my sins, despite my believing in the gospel of passive investing (we can discus why I’m active some other day).

I’m used to choppy asset prices, and to an extent I seek it out.

Yet on what they’re already calling the Black Monday of August 2015, I was newly dumbfounded.

I had cash ready to deploy into certain US companies, if I could get them at the right price.

So I waited and watched the US markets open – only to be left open-mouthed as the prices of huge firms like Apple, Facebook and Visa fell 10% or more on the off.

It was almost what I’d been waiting for. Yet I did nothing.

Why?

Because it was almost but not quite what I expected.

The deep price cuts were too much, too mad, too crazy.

I was shocked.

I remembered the financial panics of 2008 and 2009 and I wondered if I’d misread the situation. Was it happening again?

This moment seemed to last for an age as I dithered over whether to buy.

Then suddenly prices reversed and began speedily climbing (which seemed equally strange) and a company that I might have bought at 5%-off now seemed expensive at 7% lower – because 30 seconds ago it had been 15% down!

This craziness lasted barely five minutes in total, and by the end I’d bought … nothing.

So much for the bold old investor!

Cliff notes

That’s what markets do. They surprise you and unsettle you.

In response to the reader’s comment about falling off a cliff, another Monevator regular said: “This isn’t a cliff.”

And he’s right, according to the history books. Markets have fallen much further than 10%.

But perhaps for that reader, it was a cliff – even if statistically a 10% fall is nothing to write home about.

You’ll know when it’s a cliff for you when you feel it in your stomach.

Prepare yourself for a normal 10% correction and you’ll not be prepared when markets fall 20% or 30%.

Prepare for that and you’ll still feel sick from a 50% plummet like we saw a few years ago.

Been there, done that?

Perhaps they’ll fall 80% in our lifetime.

Who knows?

This uncertainty is paradoxically why equities can be expected to return more than cash over the long-term.

People hate this uncertainty, they hate the random plunges and swoons, and they hate the long periods where you feel like you’re banging your head against a brick wall for getting into shares instead of saving into cash, buy-to-let property or premium adult phone lines.

As a consequence, people under-invest in shares, and they over-invest instead in cash, bonds, and property.

And so most of the time those of us who do bite the bullet and buy shares get rewarded with superior gains over the long term.

Most of the time – but not always.

Expect the unexpected

If the volatility of equities was truly predictable – if a 10% correction did come along every 10 months, or whatever the statistics imply – then nobody would be too concerned by it.

Perhaps you’d book your holiday to coincide with the falls, and avoid all the fuss entirely.

But that’s not how markets work.

Markets do things like go up when the news is relentlessly terrible for years – and then plummet on a blue sky day.

Or you’ll have heard that shares “climb a wall of worry” and so you’re happy because everyone seems scared – and then the market crashes anyway, right in the face of that fear.

Or shares fall hard like in 2000-2003, and so people talk about a once-in-a-generation cratering – and then they crater again just a few years later.

That’s only once in a generation if you’re a gerbil with great grand kids.

The truth is you don’t know what shares are going to do. You just don’t.

You might think you do – that you’re girded for the long-term returns and for short-term volatility – but then, say, the whole world turns Japanese for three decades and even after dividends you barely break even.

Do I expect that to happen?

No.

But it might.

Known and unknown unknowns

- Nobody expected interest rates to be held near-0% for six long years.

- Few expected super-safe 10-year government bond yields to wallow below 2% – or to turn momentarily negative in Germany.

- Newlywed home buyers in Tokyo in 1989 did not expect to be underwater 30 years later.

- No gold bug expected the metal’s price to fall under $1,200 back in 2011 when gold was hitting new all-time highs above $1,800.

The subsequent fate of these surprising outcomes is misleading.

After a few weeks, months or years, they lose their power to shock and we come to accept what happened as just another data point.

They seem less scary then, and we return to believing we know what’s going on.

But do we?

Something else we don’t expect is already waiting in the wings.

Back yourself

You don’t need predictions from a talking head about where the market is going to go in the next six months.

Nobody really knows is the fact of the matter.

Deep studies have proven that rules of thumb for forecasting the market don’t work.

In general, some people are just better at talking like they know what’s going on than others – especially if they also happen to have been lucky recently.

Equally, you don’t need me to tell you to stick to your volatile equity allocation because the stock market will come good in the long term.

You need to be able to find that voice for yourself.

I love it when a plan comes together

The reality is you cannot be certain that even a well-diversified All-Weather portfolio will eventually deliver the returns you expect it to.

If you’ve done your planning properly then the chances are it will.

But it might not.

You have to understand that investing is the ultimate example of our brain’s capacity to anticipate the future and contemplate uncertainty (as opposed to living on your monkey brain’s fight-or-flight wits) but also that to prepare for the future is not to claim to predict it.

You need to create a financial plan that reflects this reality. Take your time.

Your plan should be:

Beyond that, it’s your plan, and it needs to be specific to you.

Whatever it becomes, you need to be able to stick to your plan when times get rough.

Not because things might not be rough for a reason – who knows, the boat might well be sinking – but because it was your best, most rationale, most well-considered plan that you devised on a calm day when you were thinking straight.

The chances are that if things now seem rough enough to give you second thoughts then you’re also being emotional.

That will play havoc with your perceptions and decision making abilities.

Better to act dumb.

What have you signed up for?

Lash yourself to your plan like Odysseus had his men tie him to his ship’s mast.

That way you should avoid throwing yourself into the sea.

Why not stuff your ears with metaphorical wax if you’re a passive investor, too?

Odysseus had his men do that, so they avoided the sirens’ song altogether 2.

Treat your investing like you buy your house – just get on with it, month in, month out, and don’t panic at every headline.

When I asked my co-blogger how he was doing during the last wobble, he told me that he was feeling fine, but that it might be because he hadn’t actually looked at his portfolio for several months.

Months!

Is that wise? It’s at least worth thinking about.

His investing runs automatically. It will go on like a robot slave, shunting money from his bank account to his diversified passive funds regardless of his opinion about the front page of the Financial Times.

It will throw money into the abyss if it comes to it.

Some will say that’s madness. Others will say it’s the height of passive investing wisdom.

I say it’s a plan. It’s his plan, and that’s why he can stick to it.

What’s your plan?