A lament regularly heard in school playgrounds across the land goes something like this:

“Eeeeeuuugggh! Shuuuttttt up!”

…followed by:

“Girls are gross!”

So proclaims generation after generation of little boys – only a few years before the hormones kick in and they spend the rest of their lives obsessing over women.

As goes the birds and bees, so goes home ownership.

People love to debate renting versus buying a home, the imminent collapse of house prices, or the stupidity of tying themselves to a mortgage when they could be travelling the world.

If they’re young and politically-aware, they may even decry the whole thing as a capitalist con. (Been there, probably still have the T-shirt).

But in practice nearly everyone buys their own home as soon they’re able to. And if they can’t then they aspire to.

What’s more, most of us buy our homes with little more thought than went into that five-minute mumbled lecture from your parents that they hoped would pass for sex education.

We simply buy our homes like our parents did – and their grandparents did before them.

Other ways to think about home ownership and mortgages

I’m not going to argue for a big change in the mechanics of how to buy a home.

Innovation in home ownership is usually cancerous – mostly doing local damage (timeshares, endowment mortgages) but sometimes metastasising (think Great Financial Crisis).

But I would like to remind you of some different ways to think about home ownership and having a mortgage, and how both can fit into your overall investment posture.

If you don’t own your own home then you’re ‘short’ one house

We all need somewhere to keep us and our stuff dry. Somewhere safe to sleep at night. You can either own this home or rent it.

If you don’t own a home then you’re effectively ‘short’ one, in financial terms. You have to borrow a home off someone else who owns it, and you pay the going rate to do so (the rent).

Shorting residential property is risky. In the UK house prices and rents have risen inexorably for many generations.

You close this housing short when you buy. If house prices fell while you rented then you benefitted from being short. If they rose you lost out. (Ignoring transaction costs).

Once you’re a homeowner you have a market neutral position. If you choose to buy more homes – via buy-to-let say – then you become overweight residential property.

Repaying a mortgage is the same as saving more cash

People tend to think of a repayment mortgage as a monthly expense.

They know they will own their home outright at the end of the mortgage term.

But they see the regular repayments as an expense that they mentally bucket exactly the same way as they would rent.

They usually don’t think of their repayment mortgage as contributing to their savings rate.

However repaying a mortgage on your own home is a very different financial move compared to paying rent.

Your monthly repayment mortgage direct debit consists of two parts:

- You pay the interest you owe to the bank in return for it lending you the money you need to buy your home.

- The other part pays down the outstanding loan. These payments will eventually reduce your mortgage debt to zero. Then you’ll own your property outright.

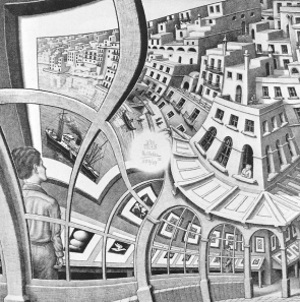

This graphic from our mortgage calculator shows these two parts for a repayment mortgage:

Here we see a £100,000 repayment mortgage that costs 3% being paid down over 25 years.

In the early years you can see you’re paying interest more than paying down capital.

But towards the end, capital repayment – effectively savings – makes up most of the money sent to your bank.

- The interest payments are an expense. They are the cost of having a mortgage.

- The capital repayments that reduce your outstanding mortgage are savings. They reduce your debt and increase your net worth.

You might think of an outstanding mortgage as a savings account that starts deeply in the red.

As you save money by repaying your mortgage, you move this ‘negative savings account’ towards a breakeven £0 balance.

Paying off your mortgage does not reduce your exposure to property

The market value of your home as house prices fluctuate has no bearing on your mortgage being effectively a savings account.

And the balance of that savings account does not affect your exposure to property.

Your house is an asset and an investment that is worth whatever someone will pay for it.

This is true however you financed buying it – whether with cash, an interest-only mortgage, a repayment mortgage, or some other less legal arrangement.

Separately from this, your repayment mortgage is a debt that you’re paying off over time.

True, this debt is secured on your home. But unless something goes very wrong – you lose your job at the same time that house prices crash and your bank decides to foreclose – house price fluctuations don’t impact your existing mortgage.

By the same token, paying off a mortgage doesn’t change your exposure to property one jot.

Having a smaller mortgage will make your finances more secure (because you have less debt).

But the affect house price moves have on your portfolio and your net worth is independent from how you happened to finance your home, and of the balance on your mortgage.

A mortgage is money rented from a bank

When you buy a house with a mortgage, the bank gives you money to make the purchase.

Let’s say it gives you £200,000.

Party time! You’ve swapped ‘wasting money on rent’ for owning a home of your own.

Well, yes, but you might want to turn down the music – because it turns out the bank didn’t give you that £200,000 for nothing.

No, it wants interest on the mortgage.

It’s as if the bank leased you the money. You’re paying to rent the money off the bank.

- At 5% over 25 years, borrowing £200,000 will cost you £833 a month in ‘money rent’

You have swapped rent payments to your landlord for rent payments to your bank.

Note that if you only ever pay your money rent and nothing else (like with an interest-only mortgage) then you must give back the £200,000 borrowed at the end of the mortgage term.

Just the same way as you hand back a rented house to your landlord when your lease is up.

To avoid this, you must repay the bank’s capital, too.

Seen another way, with a repayment mortgage you’re effectively buying £200,000 in cash from the bank, in monthly instalments, with interest.

A landlord is someone who rents money on your behalf

Instead of thinking of your landlord as someone who owns the house or flat they rent to you, you might think of a landlord as someone who borrows £250,000 or £500,000 or whatever to buy the property on your behalf.

They borrow the money required, and as a result you don’t need to do so.

You pay them rent in return for them borrowing this money. The cost is usually marked up for their trouble, so your rent is higher than if you’d rented the money from the bank yourself.

In addition, your renting hands the option on any rise in the property’s price to your landlord.

Then again, you’re also insulated from the risk of falling house prices.

You can go quite far down this rabbit hole.

You can also think of a fixed-rate mortgage as like a bond

A fixed-rate mortgage is like a bond.

From the point of view of the lender it’s an asset which pays an income, secured against an asset to reduce the risks of default.

Hence when you take out a fixed-rate mortgage – which is for you a liability, not an asset – it’s as if you’re shorting bonds.

Of course you might also own bonds in your portfolio. Maybe you have a typical 60/40 asset allocation, for instance.

Factor in your sort-of short bond position as represented by your mortgage, and your bond exposure will go down. Your overall posture may be riskier than you thought.

You can get very cute and calculate the money-weighted duration and interest rate exposure represented by your mortgage and your bond portfolio.

That’s probably not worth it though. Bonds are typically in a portfolio to dampen risk from equities, not to express a view on interest rates. And you got a mortgage to buy a house!

I’ve seen people do it though.

The Bank of England does not set mortgage rates

Unless you have a tracker mortgage that is explicitly linked to the Bank of England’s Bank Rate, your mortgage rate is not set by the UK’s central bank.

Rather, mortgage rates are based on swap rates – effectively the clearing price of debt of various durations in the open market.

Of course, the Bank of England is a player in this game. But we’ll leave debating whether it’s a leader or a follower for another day.

It’s also worth noting that mortgage lenders make their return via fees as well as the interest rate they charge.

And given that nearly all mortgages are two-year or five-year fixes – so they’re renewed several times over any mortgage term – these fees add up.

Indeed researchers have shown that lenders often explicitly lower mortgage rates but jack-up fees to appear more competitive in the market.

Your own home is an investment and an asset

Lots of people don’t think their home is an investment or asset.

I’ve burned thousands of words trying to explain why this is wrong. Please read them if you still don’t get it.

No, your home being an investment and an asset doesn’t mean it’s exactly like shares, or that you’re explicitly speculating on house price gains, or that you thought of it as an investment when you bought it, or that house prices can’t go down, or that you don’t need to repair the roof – or any of the other handwaving people do when they’re busy being wrong about this.

It means your house is an investment and an asset.

Nothing more, nothing less.

Running a mortgage while investing is like leveraging your portfolio

A big advantage of looking at all your assets as being part of your investment portfolio is that it enables you to see where you stand in the round.

For example, you’ve secured a mortgage against your house. But when you choose to invest in shares instead of paying off your mortgage, you’re effectively leveraging up your portfolio because you’re not paying down the debt.

Congratulations! You’re running a DIY hedge fund!

Personally I think this is not a bad idea for young people with strong earning prospects, tax shelters to fill, and a long investing time horizon ahead.

But it is a risk – and one many people don’t appreciate when they do it blindly.

Indeed many times I’ve been chided for running my interest-only mortgage while investing, only for it to transpire that my critic is saving in a pension while they too have a mortgage.

Nothing wrong with that, but it’s more or less the same thing.

A mortgage is a hedge against inflation

Investors spend a lot of time fretting about how to hedge their portfolio against inflation.

It’s time well spent. Keeping ahead of inflation is a prime mover when it comes to investing.

However I seldom see home ownership mentioned in these discussions. Perhaps that’s because as we’ve just covered, many people think of their home as something other than an asset. (What, we might wonder? A daydream? A mirage? A poem?)

As a result they put the mortgage in a separate mental bucket to the rest of their portfolio, too.

However a house is typically the biggest asset most people own for most of their lives.

And happily, property prices have outpaced inflation for many, many decades.

Better still, you typically buy a home with a mortgage. This debt is partly paid off – in real terms – by inflation. The nominal money you owe is worth less in the future as inflation erodes the real value of each pound.

In my view a mortgage is such a great inflation hedge that it seems worth continuing to run my big interest-only mortgage indefinitely, despite the extra risks from doing so.

Most people’s own home is their best investment

I’ve previously explained why for most people their own home is their best investment.

This has nothing to do with the prospect for house prices today, or whether shares are cheap or the stock market is about to crash.

Rather it’s that buying your own home closes a risky short position, as we discussed above, and then imposes the toughest saving and investing regime most people will ever muster.

Still, it’s interesting to think about how well your grandparents who made a fortune buying a ‘cheap’ property a gazillion years ago might have done from the stock market if they’d treated shares the same way as home buying:

- Save into the stock market each and every month, like they did with their mortgage

- Invest sensibly after researching the best options

- Ignore price fluctuations for years at a stretch

- Hold on for the long-term because selling is a hassle

- Leverage up their portfolio 5-to-1

- Not calculate their gains for 25-50 years, and even then ignore inflation

- Get all the returns tax-free, like you do with your own home

You’ll notice of course that Monevator readers who invest in index funds within ISAs and SIPPs and ignore the market noise are actually doing most of this – just absent the leverage. (Because you can’t get a mortgage to buy shares).

And global equities have delivered far higher returns than UK property prices after costs over the long-term.

Perhaps even with the lack of explicit gearing for share portfolios, choosing the ‘best investment’ crown will be a tougher call in the future?

Bringing it all back home

To be clear I don’t think you should walk into Nationwide and ask for a bond-like mortgage so you can leverage your portfolio by renting money, instead of having your landlord do it for you.

Not least because it’ll see them asking you to please leave the premises.

These are simply different ways to think about money, investments, and mortgages, which can help you see where you stand in interesting new ways.

That said though, more flexible thinking can deliver concrete real-world outcomes.

When I struggled to get a traditional mortgage based on my pretty unimpressive annual earnings, thinking differently saw me borrowing backed by my portfolio.

Applying the principles

Today my portfolio is far bigger than when I took out the mortgage and I’m earning more, too.

If I was assessing myself like a public company, then my debt-to-equity ratio is lower and my interest cover ratio is improved.

I do own some bonds as well as having a mortgage. As we’ve seen above the bonds are effectively negated by the debt, but they enable me to keep my ISAs fully-loaded and they might deliver a rebalancing bonus now and then.

In the meantime inflation continues to erode the real terms value of my mortgage.

Hopefully my active investing returns will outpace my own home as an investment though!