Part one of this two-part series explored why the future expected returns of the 60/40 portfolio are unlikely to match the last ten years.

In a nutshell, negative real bond yields plus richly valued US equity markets imply weak capital growth ahead.

Past experience shows expected returns predictions are more reliable than some chancer with crystal balls telling you that a dark, handsome stranger lies in your future. But not by as much as you’d think.

Still, a deluge of fiscal stimulus and near-zero interest rates has created a sticky financial quagmire. As a result, returns could be muted for a while.

In the face of all this, you can better position your 60/40 portfolio. But there are no magic bullets.

The alternatives come with consequences.

I’ll take you through the non-magic bullets you can fire in a moment.

First though, let’s talk about what not to do.

Don’t buy it

Improving expected returns typically means taking more risk. That’s the trade-off ignored by most of the 60/40 portfolio articles dominating Google.

Here’s a selection of their suggestions for your portfolio:

- Uranium

- Big tobacco

- Russian equities

- Private equity

- Hedge funds

- Timber

- Collectibles

- Music royalties

- Currency trading

- Junk bonds

- Chinese government bonds

- Infrastructure

The correlation between these ideas? They offer hope and are difficult to falsify. So let’s be clear. This is rampantly speculative stuff from the Donald Trump School of Medicine.

These articles are mostly generated by active managers and / or journalists. Their stock in trade is the turnover of ideas, not their quality.

60/40 portfolio: guiding principles

Recall that the 60/40 portfolio’s asset allocation aims to:

- Control risk and cost.

- Be simple to understand and operate.

- Work for investors with little interest in the market’s machinations.

None of those principles apply to the schemes I listed above. Mostly they’re complexity masquerading as strategy:

- Each ‘idea’ increases your exposure to risk and cost.

- They typically involve chancing your arm in opaque markets, which shortens your odds of being the sucker at the table.

- Little to no evidence is given to explain why these options are a good choice.

Sure, a couple of those suggestions may outperform a 60/40 portfolio in the next ten years.

But which ones?

In contrast, the following articles deploy evidence and data to expose how directionless some of those ideas are:

As for Russian equities – they have been abysmal since at least 2007.

Moreover, autocratic leaders like Vlad Putin and Xi Jinping derive credibility from painting the West as an adversary.

Good luck landing outsized future cashflows as a foreign owner of Russian or Chinese securities.

Ditch bonds

The other ‘big idea’ you hear a lot these days is to drop bonds.

That’s because owning a large holding of government bonds right now is like riding a bicycle with a slow puncture.

But getting rid of them – or even switching up to a 80/20 portfolio? That ignores why government bonds are a mainstay of the 60/40 portfolio.

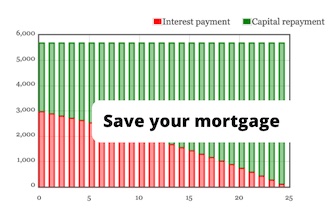

Holding bonds was never about earning big returns. The point of bonds is to lower the risk of you selling out when stocks crash.

Bailing can permanently damage your returns.

Yet this danger of cracking under pressure is not well understood, especially given how a bull market buries memories.

Panic is an insidious threat because we underestimate it.

Markets can be more brutal than most of us have experienced.

That’s why bonds are still a good investment, even today.

Some commentators state bonds can no longer protect your portfolio, but that’s not true.

These pieces show you why bonds retain some protective power, even at negative rates:

Alright, that’s enough about what not to do. Now for some practical suggestions for 60/40 portfolio investors.

Can you take more risk in your 60/40 portfolio?

The risk of investing in volatile asset classes means the answer to our malaise isn’t: “throw your bonds overboard.”

However, can you live with fewer bonds and more equities?

Can you handle a 70/30 portfolio, for example?

The answer will be very personal.

I’ve previously compiled the best advice I’ve found on risk tolerance to help you explore this issue.

One option is to try an industry-standard, online risk tolerance questionnaire. The idea is to discover the riskiest allocation you can comfortably deal with.

The big debate is whether such questionnaires work. The finance industry has used them for ages. But clearly they’re an imperfect measure.

So only increase your equity allocation cautiously and thoughtfully.

More risk, more reward?

Beyond incrementally revisiting your asset allocation, I wouldn’t recommend making changes on the risky, growth side of your portfolio.

That’s because the other options increase your exposure to investment risk and/or the risk of being ripped off.

For instance, long ago I invested in risk factors. The promise was outperformance in exchange for more risk.

Of course, I knew there was a chance my factor bets would disappoint.

Guess what?

I got the risk but not the reward.

Oh, and let’s shoot another white elephant in the room while we’re here.

The SPIVA study shows that active management is no solution either.

Remember, all the active money in the market – added together with all the passive index funds – is what makes up the market.

That means active management is a zero sum game because when one active fund wins another loses. Or more accurately: when one actively invested dollar or pound beats the market, another must do worse.

Active funds in aggregate can only deliver the market return – minus their higher fees.

The bond trade-off

Is there more you can do with your defensive asset allocation?

Perhaps.

Today’s government bond environment feels like a Tarantino-style Mexican standoff:

- Long bonds are your most potent protector against a deflationary recession.

- But they could inflict equity-scale losses if inflation runs wild.

- Index-linked bonds are your best defence against galloping inflation.

- However they won’t do much in a recession. And their yields are more negative than conventional bonds.

- Short bonds are as much use as a concrete zeppelin in a recession.

- But they’ll do okay-ish if the issue is inflation.

- Cash should be part of your mix, but it isn’t a panacea.

Which way do you turn?

Many fear the return of 1970’s stagflation will financially embarrass us like a kipper tie of woe. Meanwhile, the next recession is a ‘when’ not an ‘if’.

We need a portfolio for all weathers.

An intermediate gilt ETF holds short and long UK government bonds. It’s a muddy compromise that offers decent downside protection in a recession.

And owning some inflation-resistant, index-linked government bonds is de rigueur – even though they are expensive.

I discussed some linker options in this post. (Another global index-linked bond ETF (hedged to GBP) has come onto the market since.)

Fiddling around the edges

Higher-yielding bonds like corporate bonds and emerging bonds are not an alternative to high-quality government bonds in a 60/40 portfolio.

Emerging market bonds behave more like equity. You don’t need them.

Investment-grade corporate bonds offer a little more yield in exchange for less protection than high-quality government bonds.

You’ll probably see owning US Treasury bonds mentioned, too. It’s a decent idea that could offer a smidge of extra return. But it only works under specific conditions. And the risks need to be understood.

You’ll have noticed by now that every ‘if’ comes with a ‘but’.

I prefer to keep things simple:

- Equities for growth.

- Index-linked bonds for inflation protection.

- Cash for short-term needs.

- An intermediate bond fund to cushion stock market falls.

However, I’ve been tipped off about a bond allocation that might work more effectively in the current conditions.

It’s an advanced strategy that requires a good understanding of bonds.

Long bond duration risk management

One logical response to a low yield world is to make like American politics and move to the extremes.

That means replacing intermediate and short bonds with long bonds plus cash.

This barbell approach hopes to capitalise on:

- The slightly higher yields of long bonds.

- Their better track record in recessions, relative to other bonds.

- The low duration risk of cash. This offsets the vulnerability of long bonds to rising market interest rates.

Here’s an example:

Desperate Daniella holds 100% of her bond allocation in an intermediate gilts fund with a duration of 10.

She replaces that fund with:

- 50% Cash (duration 0)

- 50% Long gilt fund (duration 20)

Daniella’s reallocation still leaves her with a weighted duration risk of 10:

- Duration 0 x 50% = 0

- Duration 20 x 50% = 10

The long bond duration risk is dampened by the cash.

This is not a free lunch. It gives you greater exposure to the longer end of the yield curve. That could be hard to live with should that part of the curve steepen in response to, say, spiraling inflation.

The idea comes from Monevator reader and hedge fund quant, ZXSpectrum48k. I’ll refer you to some of his comments on the topic:

What about gold in the 60/40 portfolio?

From a strategic perspective, the best thing going for gold is its zero correlation with equity and bonds.

Gold randomly does its thing like Michael Gove in a nightclub – spasming erratically regardless of the drumbeat moving other assets.

Gold did amazingly well in the stagflationary 1970s. Back then equities and bonds got hammered. However, one-off historical factors were in play. The US Government had stopped fixing the gold price and legalised private ownership.

The yellow stuff smashed it during the Global Financial Crisis, too. But gold cushioned portfolios less successfully than gilts in the coronavirus crash.

And gold lost 80% between 1980 and 2000.

So no, gold isn’t a no-brainer. You still have to use your nugget. (Alright, that was just gratuitous – Ed).

Some model portfolio allocations like the Permanent Portfolio and the Golden Butterfly include a generous dollop of gold. How clever that looks depends mightily on the timeframe you pick.

Meanwhile, gold’s long-term return hovers right around zero. It’s crock-luck as to whether gold will work for you. The hope is it comes good when everything else fails.

For me, this boils down to a 5-10% allocation in a multi-layered defence.

Where does that leave the 60/40 portfolio?

We live in interesting times. Diversification remains the right approach.

The all-weather portfolio below is positioned for uncertainty, without sacrificing the principles that first made the 60/40 such a godsend.

- 60% Global equities (growth)

- 10% High-quality intermediate government bonds (recession resistant)

- 10% High-quality index-linked short government bonds (inflation hedge)

- 10% Cash (liquidity and optionality)

- 10% Gold (extra diversification)

This asset allocation maintains the 60/40 portfolio’s balance of growth and risk. Granted, it adds complication. But every asset has a clear strategic role.

That makes more sense than knee-jerking into private equity and uranium.

Remember the 60/40 portfolio was never a get-rich-quick scheme. It gained traction because it was good enough.

For more:

High-quality government bonds means gilts or a developed market government bond fund hedged to the pound.

Taking control with a 60/40 portfolio

The more effective countermeasures you can take are technically simple but emotionally difficult.

You can’t control future asset returns. But you can control these mission-critical factors:

- Contribute more money to offset lower growth expectations.

- Increase your time horizon to benefit from compounding.

- Lower your financial target to make it easier to hit. That ultimately means living on less, if we’re talking retirement.

To see what a difference this makes, run your numbers in a calculator like Dinky Town’s Retirement Income Calculator.

Adjust contributions, income target, and time horizon to suit your circumstances.

See how things look under a range of expected return scenarios. Try plugging in optimistic, pessimistic, and middling predictions.

For example, these expected return forecasts come from Vanguard:

- Optimistic: 4% (75th percentile)

- Mid-ground: 2.6% (Median outcome)

- Pessimistic: 1.2% (25th percentile)

Those are 10-year annualised expected returns for three alternative universes.

To turn those into real returns, I’ve subtracted an average annual inflation guesstimate of 2% from Vanguard’s nominal figures.

Put the expected returns into the calculator’s rate of return field via the Investment returns, taxes, and inflation dropdown.

Periods of lower (higher) returns tend to be followed by higher (lower) returns. Accordingly, you can hope for improved growth beyond the next ten years. The Dinky Town calculator lets you play with that, too.

The three most powerful changes you can make are putting more money in, waiting a little longer, and lowering your income bar.

They also save you from meddling with your 60/40 portfolio if that suits your risk tolerance.

Not-so-great expectations

Multiple crises over the past 15 years have trapped us in an escape room with no easy way out.

I wish there was a clear answer to this puzzle but there isn’t.

Taking action now means short-term pain for long-term gain.

On the other hand, what if the next decade exceeds expectations?

Hallelujah! We’ll be better off than we thought – living on more or retiring earlier.

In conclusion: fingers crossed.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator