Everyone says our homes cost too much to buy. But few look deeply into UK historical house prices for context.

Yet if you were to go back through the ages with a time-traveling estate agent in a TARDIS (period features, surprisingly roomy, in the same family for 900 years) you’d find it’s been a long while since British homes were cheap.

Even when property looked more affordable – the 1970s, say, or briefly in the 1990s – there were other things going on.

High unemployment, punishing interest rates, recession, or a more restricted market for mortgages.

With that said, the housing market did start to undergo a step-change roughly three decades ago. In hindsight, the advent of buy-to-let mortgages and steadily falling interest rates kicked off a 30-year housing boom. The tax advantages enjoyed by landlords versus homeowners didn’t hurt, either.

This all eventually made property more expensive on historical measures, such as the ratio of house prices to earnings.

But wait!

Like everybody who talks about house prices, we’re already rushing to diagnose what (supposedly) ails the market.

For today, let’s just look at UK historical house prices through various lenses, to put current prices into context.

House price growth over the past ten years

The average new home in the UK costs £294,845, according to Halifax. That’s an all-time record.

What’s more prices have been rising at an 11% a year clip.

At a time when wider inflation is approaching double-figures, this rate of gain may not seem so shocking for once.

Then again, the persistence of any price growth is a bit surprising. We’re at the tail-end of a pandemic, after all. Most other assets have crashed this year. Not coincidentally, interest rates are rising. That directly leads to costlier mortgages.

So is property simply proving its worth as a store of value? Or is this ongoing strength an anomaly?

Well UK house prices have already been climbing for ten years. See this graph from the Financial Times:

Source: Financial Times

Note that the Financial Times is using Nationwide figures. Nationwide has house prices a little lower than the Halifax ones I quoted earlier.

Indeed it’s worth knowing that all the different house price data compilers use their own data sets. Each with its own quirks. Nationwide excludes buy-to-let purchases, for example.

According to Nationwide the average UK home now costs £270,452.

That compares to £164,955 in 2012 – a total price gain of 64% in a decade.

However that figure isn’t adjusted for inflation.

Most things are more expensive than in 2012, right?

Ten-year house price growth: after-inflation

We can use the Bank of England’s cute inflation calculator to convert the price rise cited by Nationwide into real terms. (That is, inflation-adjusted).

Inflation data for 2022 is not yet available. Let’s therefore use 2021 as our base year, given how hot inflation has been running for the past eight months.

- Nationwide says the average house cost £251,133 at the end of 2021

- At the same point in 2011, the average house cost £164,785

Using the Bank of England’s calculator, we can see that the 2011 house price equates to £196,776 in 2021 money. (That is, adjusting for CPI inflation.)

Play with Monevator’s compound interest calculator and you’ll see that it takes about 2.5% a year over ten years to turn £196,776 into £251,133.

Therefore house prices went up by about 2.5% a year ahead of inflation over the ten years to 2021.

This is mildly interesting for property nerds. But it gets more dramatic looking further back.

Consider that by the end of 1991 the average house cost £53,635. That’s £99,618 in 2021 money.

- In nominal terms, house price growth was about 5.3% a year over the 30 years from 1991 – or 368% overall.

- But in real terms – after-inflation – annual growth was only a little over 3%, or 152% in total.

Clearly 152% is a lot less vertigo-inducing than a 368% nominal terms price rise.

Although as we’ll see later on, it’s still a lot faster than wages have grown. Which is why we keep hearing about a housing crisis!

(It’s also a reminder of how property has protected you against inflation).

Real UK historical house prices: a longer-term view

Nationwide produces an alternative real price index. It saves all this mucking around doing estimates with calculators.

Here’s how Nationwide’s real average house price has risen since 1984:

Interestingly this graph suggests that – in real terms – house prices are yet to recapture their 2007 pre-financial crisis peaks.

Conversely, you can argue it’s a bit silly to adjust asset price inflation by changes in the price of a basket of goods and services. But that’s for another day.

Very long-term UK house price history

It’s fun to induce vertigo by looking at the Nationwide and Halifax price data via longer-term charts. Download the Nationwide series and you can do so yourself.

Alternatively, you can wait for someone else to do it for you – the media is forever knocking such graphs out.

For instance one-time Monevator contributor Tejvan Pettinger recently published this chart showing UK historical house prices spanning more than 50 years:

Source: Economics Help

Any graph that rises from (apparently) near-zero like that will grab your attention. But remember these property values are not adjusted for inflation.

And is even 50 years a long enough time over which to evaluate house prices?

The UK is a very old country. And we’ve been buying and selling property since well before The Beatles released Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

The long, long-term: house price history before Hitler

Academics have made various stabs at estimating the returns from property over more than a century.

For example, in the paper The Rate of Return on Everything: 1870-2015, the authors calculate that the very long-run return on property across 16 countries was just over 7%, in real terms.

Interestingly that’s very similar to the long-term real return from equities.

However this 7% annual return isn’t comparable to the house price series we’ve been looking at. That’s because its property values also incorporate the return from rent, to come up with a total return. In contrast, the house price data series only track prices.

But a bit later on the same paper estimates UK capital gains on housing since 1895 at 5.4% in nominal terms, or 1.25% real.

Which would indeed suggest the past 30 years have been a bit frothy, historically-speaking.

Meanwhile a more recent paper, The Best Strategies for Inflationary Times, pins UK annualised real housing returns from 1926-2020 at 3%. And as best we can tell that’s capital gains only. (It’s based on ONS data, which uses Land Registry house prices.)

My interpretation of these studies – together with the data from Nationwide and Halifax – is that property prices in the UK have been going up for over a century, but that growth has accelerated in the past few generations.

This would correlate with the popular notion that an increasingly egalitarian Britain has steadily transformed from a nation of renters to homeowners. At least until the past decade or so, when sluggish wage growth hurt affordability.

It’s fascinating research, with a lot of nuance and discussion that I’ve glossed over in this quick summary. Dive into the papers for a more thorough perspective.

How much do house prices go up in a year?

Looking at long-term house price history charts can be deceptive. The steady line rising from the bottom-left of the graph to the top-right makes a house price boom look as smooth as ascending a ski-lift on a windless day.

However just as icy gusts will rock your cable car, so house prices actually move in fits and starts.

Study the historical house prices graph below, which charts annual changes over the past 30 years:

Source: Nationwide

At first glance you might wonder how today’s prices are any higher since 2002. The graph appears to move downwards as you go from left to right.

Remember though, this is plotting annual house price changes. Not the absolute level of house prices. Anything above 0% represents a year when prices rose.

Looking more carefully, we can see there was a huge boom at the turn of the century. House prices rose by at least 10% a year – and as much as 25% – between 2002 and 2005.

Growth continued at a slower pace until 2007, when the market cooled. You’re seeing here the impact of the global financial crisis.

Don’t believe anyone who says house prices never go down! The chart shows that by mid-2008 prices were falling 15% year-over-year.

However this crash was short-lived. The Bank of England cut interest rates, and mortgages became much more affordable.

The falls soon turned around. And by 2014 house prices had recovered much of their losses.

Another brick in the wall: small annual gains add up over time

It’s interesting to note how often prices barely budged in the years between 2012 to 2022. Especially compared to that 25%-a-year surge of two decades ago.

Yet despite this sometimes-sluggish market, we saw in the ten-year price FT graph at the start of this article that house prices overall rose around 60% between 2012 and 2022.

This underlines that property is best approached as a long-term asset. Especially given the high cost (and hassle) of buying and selling. Inconsistent annual gains add up mightily if you give them enough time.

Indeed most people feel they do better with their own property than their pension precisely because they get on the property ladder for the long-term. They ignore its short-term fluctuations, and instead they commit to holding on to their homes.

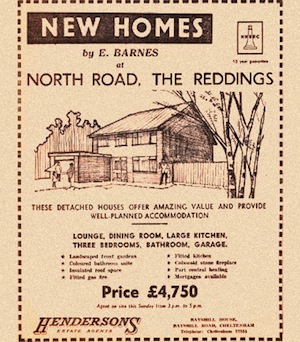

This is exactly what leads to your parents or grandparents sitting in houses they bought for what seems like peanuts compared to today’s prices.

Historical house prices compared to earnings

The absolute level of historical houses prices is endlessly fascinating for Britons. But what really matters from the perspective of a would-be buyer is how affordable they are.

If the average annual salary was £100,000, say, then an average house price approaching £300,000 would be cheap-as-chips.

Buying such a home with a 90% mortgage would cost you £1,365 a month, with a 3.5% repayment mortgage over 25 years.

Assuming £5,500 of take home pay after-tax, our £100K earner would have plenty of spare cash leftover each month for Netflix subscriptions and avocado on toast.

But of course most people earn nothing like £100,000 in 2022. The median average salary of full-time UK workers is £31,285.

Hence all the hand-wringing about home-owning being out of reach for young people.

The time-honoured way to show this is by plotting average house prices against earnings over time.

Again, back when I first fretted about a housing bubble – you probably weren’t born – you had to do this for yourself in Excel.

Nowadays the data providers do it for you in your web browser. (Seriously, you may not be able to afford your own home but just look at your Internet go!)

Here’s 30 years of the house-price-to-median-earnings ratio for the UK (pink) and also London (green):

Source: Nationwide

The merest glance at this graph shows you why people feel property values have become more expensive – particularly in London.

It’s because it has!

When I first started looking for flats in the mid-1990s, the price-to-earnings ratio in London was barely three. Whereas it now costs nearly ten-times the median income to buy an average home in London.

The wider UK ratio has escalated just as dramatically, albeit from a lower base. And unlike in London it’s still climbing.

Previously I’d end the story here. But in 2021 researchers from Schroders threw this intriguing graphical cat among the price-to-earnings pigeons:

Source: Schroders

The Schroder analysts dived into a millennia of data from the Bank of England to produce this 175-year chart of housing affordability in the UK.

And you can see that in the Victorian era, UK house prices were at least as expensive as today compared to average earnings.

Quoting Schroders’ Duncan Lamont:

It may only be of historic curiosity, but it is interesting that house prices were even more expensive in the latter half of the nineteenth century. They then went on a multi-decade downtrend relative to earnings. This only bottomed out after World War I.

There are three important drivers of this: more houses, smaller houses, and rising incomes.

When I next update this article (diary note for 2032) I might try plotting this graph against interest rates to see if that’s a factor too.

Although to be frank I don’t know if there was much of a mortgage market in the early 1900s…

Don’t bet against the house

Soaring house-price-to-earnings ratios in recent years underline how higher UK house prices have made property ever more expensive for British workers.

But even that’s not the end of the story. Not by a long shot.

Most people buy a property with a mortgage. And interest rates fell pretty steadily from the 1990s until, well, this year!

So buying a property became easier to finance as rates fell, even as the absolute price level rose and wages only inched ahead.

Of course you might argue that financing costs are a different issue, at least in theory, and I’d have some sympathy with you.

But the facts on the ground seem to be that cheap mortgages have (in practice) supported higher price-to-earnings ratios for property, even as house prices climbed ever higher – just as low interest rates supported higher (in theory) prices for shares.

Of course, that (theory) ended in a stock market crash when rates finally rose.

Will higher rates do the same for property prices?

As per the Schroders’ quote above, we could also talk about what you get for your money with an average home these days, compared to the past.

Flats and houses are certainly smaller than they used to be. But some people – especially homebuilders – would stress they’re better insulated and finished.

And just look at that kitchen!

It was ever thus. Your great-great-grandparents’ loo was in their back garden. And as we’ve seen above, UK house prices have steadily ticked higher regardless.

Driven most of all by an infuriating platitude: we all have to live somewhere.

Will UK property prices keep going up?

Despite costing higher multiples of earnings, property has continued to be bought and sold every year.

It’s a functioning market, and as such its hard to call property ‘expensive’. Isn’t it just the going rate?

Many of you will disagree – perhaps I do too – and there’s no doubt we’ll be speculating about where house prices will go in the next 12 months for the rest of our lives.

But where do you think UK house prices will be in the next 30 years?

My guess: up, up, and away!

Note: a version of this article was first published in 2011. It has been re-written after another ten years of historical house prices were added to the ledger. We’ve kept the comments below for posterity. Do check their dates for context.