I’m very pleased to introduce this guest post by Pete Comley, author of the hit free eBook, Monkey with a Pin. (Now also available as an iTunes podcast). Take it away Pete!

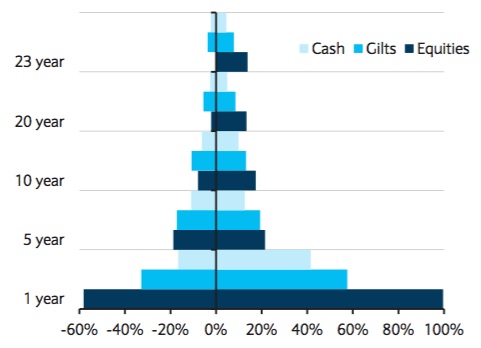

“Over periods of five years, the returns from shares have historically beaten cash around 80% of the time. Over 10 years, this rises to about 90%, and for 20-year periods, it’s 98%. With odds like that, investing [in shares] for the long term remains one of best ways of building your wealth.”

The above comment from The Motley Fool’s “10 Steps to Financial Freedom” has become the accepted orthodoxy by most investors.

What’s more, we are now living in a period of amazingly low interest rates. Base rates are at their lowest level for hundreds of years.

So what is the point of holding cash?

In this post, I will argue that the superiority of shares is not as great as the finance industry would have you believe. In addition, cash does have some key benefits like cheapness (no charges), simplicity, low risk, and optionality.

Cash is not without its own issues, and I’ll discuss how to mitigate these.

However, it is my view that neither cash nor equities are likely to beat inflation over the next five years. This article discusses how I’m going to play the ‘bad hand’ we all seem to have been dealt.

The effects of financial repression

Firstly, why am I so negative about the coming years?

It is not because of the Euro crisis per se or the stalling Chinese (and therefore world) economy. It is the debt mountain everywhere.

History suggests that there is only one easy solution for governments to this debt mountain, and that is something called financial repression.

The UK government has a track record of using this solution since Napoleonic times. It does two things:

- Firstly, it creates high inflation to erode the real value of its debt.

- Secondly, it suppresses interest rates to ensure it has to pay as little as possible to service its debts in the meantime.

The Bank of England appears to be enacting this time honoured strategy. Using QE to buy government debt not only ensures rates stay low (for the time being) but also that at some point soon all that money supply is going to fuel inflation. The blue touch paper has been lit and the fireworks display is just starting.

Historically – i.e. the last 50 years – interest rates averaged about 2% above inflation. But this is probably not going to happen over the next 5-10 years due to financial repression. Instead, even the best interest rates are going to be lucky to match it.

Equities trading sideways and consolidating

So given my views on cash, why am I writing a blog post arguing its benefits over equities?

Because equities are not going to do much better, in my view – at least not for a few years. We seem to be stuck in a sideways consolidation secular bear market, and have been for 12 years. These typically run for 13-16 years or thereabouts.

Source: Barclays Equity Gilt Study 2011. UK equity index without dividends but adjusted for inflation.

Until we break out of this into the next secular bull market (which would see the FTSE 100 make new highs above 7000), the average equity holding is going nowhere. A report by Deutsche Bank published in late 2011 estimated that the average net return of the stock market over the next decade will be barely above inflation (+0.6% per annum).

When is cash not cash

But this isn’t my main issue with the finance industries’ claim that equities outperform cash. I think their argument has some serious flaws, as I outline in my book Monkey with a Pin.

To start with, all the key comparative historical studies like the Barclays Equity Gilt Study and the Dimson, Marsh & Staunton data don’t use a measure of ‘cash’ that you and I think of as cash. They normally use something called a ’91-day treasury bill’. It is a wholesale instrument that’s unavailable to the average saver (unless you have a spare £1/2 million or so).

When they do attempt to compare with building society rates, they use accounts that no one else is using and are not representative of the market.

Since 1998, Barclays has been indexing against the postal Nationwide InvestDirect account. It pays just 0.2% (i.e. 3% below many instant access accounts). If you adjust for this alone, the gap between cash and equities narrows.

The missing 6%

As if this treatment of cash was not bad enough, in my book I also show that the average investor is losing 6% a year from their theoretical equity return.

The main reason they never achieve the projected returns that the industry promotes is charges – be they fund TERs, hidden charges, or just share trading commissions, stamp duty, and bid offer spreads.

You also have to factor in that on average, most private investors have a negative alpha (skill level), especially when new to investing.

Lastly, the theoretical return is usually based on measures that exclude survivorship bias, so that also drags down the actual return versus expectations.

When you add in this further negative 6% drag on equity investing and compare it with the real return on cash over the last ten or even 20 years, the comparison actually favours cash.

Cash vs equities scenarios

There are ways to mitigate this average 6% loss in equity investing, as I describe in my book. The key one is to buy and hold a very low cost passive index tracker, which gets your loss down to about 1% per anum.

However even after doing so, the actual equity return over the next five years is probably going to be less than inflation, if Deutsche Bank is right:

This means that the best-case scenario for both high interest rate cash ISAs and low cost tracker equity investments will not match inflation.

How to get the most from cash

Having debunked the industry brainwashing that holding cash is a completely stupid idea, let’s look at it in more detail and examine how you might best do so.

First, a big caveat: Many people will not do that well out cash.

In my scenarios above, many people will be lucky to get back any more than they put in, in real terms, if they pick the wrong ISA account (the fourth bar in the graph). But remember that I think the same will happen to the average share investor, too, by the time you factor in their missing 6% a year (far right bar above).

Indeed, the biggest issue with cash is that most people put up with receiving a much lower rate of interest than they could theoretically get.

It may hardly seem worth bothering to switch accounts for 1% or so more on the interest rate. However what most savers fail to realise is that due to compound interest, the impact is quite big, as the following chart illustrates:

We all live busy complicated lives. Although we seem happy to spend a lot of time researching exciting share opportunities, we are reluctant to spend a fraction of that effort on ensuring we get a good interest rate on our cash. Even if we start with good intentions, we often find a few years down the line that our introductory bonus rate has long expired without us doing anything about it.

Savings tip: Want to audit your interest rates? This handy tool from Which? enables you to easily check the rates on your old accounts.

How to be a rate tart

I’ll admit it, I’m a bit of tart. So what are the options I’m using (or have considered using) to ensure I maintain good rates on my cash?

1. For money I’m prepared to put away, I use fixed rate schemes for a year. They automatically write to me near the end and tell me it is expiring. That forces me to go online and compare the rate and if necessary switch provider.

2. I try and time my accounts so all the bonuses and fixed rate schemes expire at a couple of points in the year (so I don’t keep having to think about it). The March ISA season is a good expiry point to renew at good rates.

3. I am looking at using the free MoneySavingExpert Tart Alert tool. By registering the expiry date with it when you set up the account, it will text or email you six weeks before the end to remind you to switch.

4. I have looked at the Governor account. It is an intermediary website, which sends you alerts when your accounts interest rates decline and makes it easy for you to switch. Why have I not used it? A few reasons: It won’t take transfers in, it only takes fixed term deposits, it has a very limited choice of accounts (just five small building societies currently show offers), and the rates are below the best elsewhere (as Governor takes its cut).

5. I’m thinking about opening an Investec High 5 or High 10 account. These offer a rate that is equivalent to the average of the top 5/10 saving accounts, respectively. The main snags are you need a minimum of £25,000 to tuck away, and you also have to give 6/3 months notice, with no early withdrawals permitted. You can’t use it for ISA funds, either.

All in all, I am still likely to be using a manual process for accounts in the future, despite the potential financial innovations out there.

Tax doesn’t have to be taxing

Another issue with cash often overlooked in the comparison with equity investing is that of tax.

Few people pay much tax on their dividends or gains from shares because they are within their tax allowances, they are basic rate taxpayers, or else the shares are sheltered in tax-free wrappers like ISAs and pensions.

Compare this to cash savings, where many pay the 20% basic rate, if not higher rates of 40% to 50%.

The annual cash ISA allowance is (for some reason) just half the potential stocks and shares ISA allowance, amounting to £5,640. This – together with the fact that you can’t get the money out of an ISA and then put it back in – means that many of us have savings accounts where we’re paying tax.

Tax can massively reduce your returns, as the following graphic illustrates:

Sipping your glass empty

If this were not bad enough, those trying to hold cash within SIPP pension schemes typically receive near-zero returns on it.

There is a solution to this, however, which I use myself. That is to have a SIPP set up with a provider that allows you to put your cash in building society and bank accounts of your choosing. Admittedly they have to be postal-administered trustee accounts, which restricts your choice severely, but if you look at Investment Sense’s listings, you’ll see the rates similar to the usual best buy tables – indeed the current five-year fixed rates are higher than the comparative ISA ones.

A word of warning: Suitable SIPP accounts don’t come cheap in their running costs, nor in the set up charges for each building society account. You are probably going to need a pension pot in excess of £100,000 to make them truly worthwhile.

Spreading your risk

Any discussion of cash savings can’t pass without a reminder about the Financial Services Compensation Scheme. In the event of another banking crisis that threatens your cash savings, the FSA will cover you for up to £85,000 deposited with each banking group in the scheme.

To ensure you’re protected, you must understand which banks are part of which groups – see the FSA for full details. You must also check before you set up an account to make sure it’s covered at all – this is particularly important for international banks.

If you have more than £85,000 to invest, then you are going to have to open and administer two or more different bank accounts (which can significantly add to your hassle/costs in a SIPP, for example).

Optionality

Having looked at all these negatives, I’m sure many of you still think I’m mad bothering with cash. But the main reason I do so currently is optionality.

At some point in the next few years, I think there is a good chance that asset prices will mark a significant low point. If you go back to FTSE chart I showed earlier, there has to be chance that we’ll see another stock market low before we finish this secular bear market.

At that point, I want to have as much cash to invest as I can muster. I don’t want to be thinking that my portfolio has just declined 50% and the end of the world is coming. I want to be thinking positively like Buffet does in such situations. I want to be shopping in the biggest sale we’ll potentially see for another 20 years afterwards.

If I’m wrong and the FTSE does not put in a new significant low, I plan to invest when we break out of this sideways trading into the next secular bull market. At that point, the wall of cash out there is also going to pile in and drive stocks to new highs.

FTSE 20,000, anyone?

Concluding the case for cash

Holding cash at the moment is not a good idea, but in my view holding equities is potentially even worse.

I view cash as a short-term strategy to preserve my wealth in some form for the great potential opportunities to come.

So has Pete persuaded you to shake that equity monkey off your back? Or do you believe like me that now is already a good time to buy shares? Let us know below. (Note: I fully agree that cash is under-rated for private investors.)

Finally, my thanks to Pete for this very comprehensive article. Don’t forget to download his free eBook!

Comments on this entry are closed.

I agree that at some point over the next few years, the markets will move north and could well rise above 7000. The trouble is, nobody can time the markets and the probability is that by the time it become clear what is happening, those in cash deposits will have missed out on the surge.

A better strategy, imho, is to stay in the markets holding dividend yielding equities (shares or investment trusts) – collect the 5% yield (and rising year on year) while you wait for the upturn which is better than any cash deposit rates. When the markets rise, you are already on board to benefit from the capital appreciation.

My two penn’orth fwiw!

Great article, although it’s left me feeling depressed!

Using regular savers to build up a lump sum, ready for the March ISA offers is an approach I use too and have advised others to follow.

Best regards,

Guy

I personally believe that high debts themselves are a key factor in suppressing interest rates. With high debts, monetary policy becomes much more effective and any incipient inflation can be quelled at much lower rates and with much smaller increments.

Just look at how interest rates have moved inversely to debts over the last 30 years. Of course there is a chicken and egg situation here in that the lower the rates, the more it makes borrowing affordable and the more loans get taken out. However, inflation has not risen as a consequence. You could look at Chindia and say they have been effective at quashing cpi and you’d be right. But don’t ignore the effect of debts themselves in quashing inflation and interest rates.

Of course, once people suspect debts are unpayable the risk premium rises – but that is a separate component of the rate charged.

Consequently I don’t believe the popularist mantra about how all that additional base money will uncontrollably feed into a hyperinflationary episode. All the BoE have to do is to raise rates or buy back its bonds – if it wants. But of course you are entirely right in that repression is the way forward and inflation of about 5% pa suits them just fine.

An interesting analysis – which I may even agree with (that cash will outperform equities over the next 3-5 years).

But yet the ‘conclusion’ that we should therefore poo-poo equities as a result is rather invalid. The vast majority of us Monevator lot are investing for the long term. If given the choice between a smooth and steady rise over the next 40 years, or a 10 year period of no gains, followed by compensatory gains – I would choose the profile which allows me to invest nice and cheaply at the beginning of my life, and experience strong gains in the next ‘secular bull market’ when a lot more of my money is invested.

Therefore I’ll stick with the more traditional allocation.

most depressing article ive ever read about investing

suicidal

Of course the best approach is probably to use both cash and stocks and shares. In my mind the allocation of bonds or cash should be at least 25% and the allocation of stocks at least 25%. In my mind the best thing about cash is that is will adjust your returns towards 0… when you are in profit that is not so good, but who cares, you are in profit. However, when you have loses, that cash component will minimise those losses and make them more palatable.

That said I say this because I do active stock picking which ups my risk of human error and makes such a fall back a nice option to have. If I was a passive investor, perhaps the need for cash would lessen.

I read Monkey with a Pin just after it was published and it is an excellent book. New and more experienced investors will get a lot from it. Thanks again Pete.

The only part of Pete’s advice I take issue with is the ‘optionality strategy’ which is based on timing the current market. In my or rather the view of many distinguished professional investors (John Bogle, William Bernstein etc etc) this simply can’t be done. All the evidence seems to suggest that even professional investors can’t market time consistently. Any individual private investor who thinks they can market time has to ask themselves why (after costs) they are better investors than the average (made up of mainly professional investors). Even if you don’t accept the above statements, clearly ALL investors can’t market time as the market is merely the net result of the trades of ALL investors.

The only rational investment strategy is surely to think in terms of risk management:

Balance the risk of low, perhaps less than inflation returns, from not investing in equities (thereby losing the equity risk premium), against the risk of losing 30-50% of equity capital in a single bad year. To do this choose an equity vs cash + bond ratio which suits your risk appetite, age and wealth.

Stick with the above strategy through thick and thin for the long-term.

Diversify across markets and keep costs as low as possible.

Feed significant capital sums into the market gradually over 6 – 12 months.

Everything else is at best not very important detail and at worst wealth destroying snake-oil.

The trouble with the ‘sit on the side-line until the market declares itself’ strategy is that there is more risk that this strategy will lose by missing out on a sudden market rise rather than win by missing out on a large fall. After all, over the long-term markets rise – in other words there are more ‘up’ movements than ‘down’ movements. It follows that the more periods of your investing life-time that you sit out the market ‘waiting for it to declare itself’, the more chance you have of missing out on market movements the majority of which will be ‘up’.

In addition to all the information here on Monevator there is a nicely succinct summary of the above investment strategy on

http://www.longtermreturns.com/p/how-to-invest.html

All the best

Adrian

Does the UK equity index include reinvestment of dividends? Can’t make my mind up if its the right thing to do for comparison purposes.

Price inflation on its own does nothing to help household debts, it just hurts real living standards. Wage inflation would help households with debts, but we have none of that. We are nearing 0% wage inflation rates.

Price inflation absent wage inflation does not help the government much either, except if you confuse cause and effect – that VAT rises in 2010 and 2011 are the *cause* of the price inflation.

Complaining about the government “creating high inflation” to reduce its debts is frankly dangerous nonsense.

I’m with Simon Oates

Pardon my simplicity but: if you take your money out of equities into cash you are going to miss that big day equities will skyrocket. And that day you’re going to lose more than you have saved the previous years by splitting hairs with the cash-equity comparison.

Unless you can predict the moment the bear market ends he-he

I’d rather consider a bond-cash comparison.

I am a big fan of cash but I do not expect it to outperform equities over the next few years. With reducing money supply in the UK and elsewhere I do not see QE as inflationary unless it is coupled with a gilt cancellation programme.

Consequently, I do not expect to see inflation and rates move up significantly in the short term. Although I do not expect to see a bull market develop anytime soon, I think dividends from quality stocks will hold up and may even rise.

“Equities trading sideways and consolidating”. I’ve just run my monthly Severe Real S&P500 Bear Market analysis and can see a similar phenomena in the US. Looking at the historical data going back to 1881 we could still very easily see or be in one of only four severe bear markets where stocks fell by 60% in real terms. By my calculations, as of today the S&P 500 is a real 33% of its peak of August 2000.

@Lemondy

It’s even worse than your asumption of 0% wage inflation. Latest ONS data suggests it is more like -2.7%.

RetirementInvestingToday

‘we could still easily be in one of only four [going back to 1881] very severe bear markets’

Yes we could, or we could be in the middle of an even more severe bear market or we could be at the beginning of a bull market. The point is we don’t know. Someone wrote that there are only two types of investor. Those who can’t predict the market and know they can’t and those who don’t know they can’t predict the market….

@Adrian

I agree. I’m certainly in the ‘can’t predict the market and know they can’t’. That’s why my investment strategy is very much mechanical (strategic with a twist of tactical) with absolutely no emotion involved. Since I’ve gone this way I’m doing a whole lot better than when I thought I knew what I was doing.

Pete has some well thought out ideas on equities, but as others have said, he might want to review his opinions on market timing. There are ways to do this, but not with what amount to guesses on the market’s future direction.

To me this just says any new offering of index linked bonds issued by NSI or a substantial bank or company is worth a look if/when it comes out

@All — While I’m pleased we’ve all given Pete a polite hearing and I personally valued his perspective and especially his practical tips on investing cash for the best return, I can only echo the thoughts about market timing.

From my 2009 article about investing in bear markets, some interesting statistics:

Have a small cash reserve to make yourself feel better by enabling you to buy after plunges is one thing, but wholesale market timing is a lottery IMHO.

Showing a graph of real UK equities without dividends reinvested is a bit like showing real capital in a bank account without interest added….now that would be a frightener.

That said I have compared the graph with the similar graph for the US (Shiller) and the differences are so great that I have to doubt that Barclays data.

For instance, the change from 1899 to 1974 is +100% in US vs -60% in UK. Inflation was crazy in the UK then but even so…….The change from the low point of 1920 or 1921 to the 2010 level is 13x in the US vs only 5x in the UK. The change from 1952-2010 is 3.5x in UK vs 5.6x in US. I appreciate that there should be differences but these seem just too big.

I agree with many above who say market timing is not a good idea. The thrust of Pete’s book is that amateur investors are no better at picking stocks than a monkey (i.e. randomly). Why then would amateur investors be any better at market timing (and valuation) than random? I didn’t see any evidence to support this, and indeed evidence I’ve seen elsewhere like TI’s comment above is against it.

A Deutsche Bank report is quoted in the book saying stocks will do badly over the next 5-10 years and Pete interprets this as a sign to stay in cash. That’s fine, but what makes DB’s report any more valid than reports saying Stock XYZ will soar, sector ABC will crash, buy gold etc. etc. To me it’s more noise telling you to buy this, sell that even if it’s whole assets rather than individual stocks. It still encourages churn.

Pound cost averaging is dismissed, quoting a study saying you’d be better off buying straight away, as markets on the whole tend to rise. Again, this is not an invitation to time the markets – most will likely wait too long and lose out on returns. Since most people will be investing from a salary, they will naturally use PCA, and should buy when they get the money rather than trying to further average each lump of income, or wait until conditions match some magic formula. That is the take-home for me.

Pete’s book is worth a read – I enjoyed the first section which covered the consequences of high fees, lack of skill etc. Survivorship bias in particular is an interesting topic dicussed. Lots of interesting data and I agree the case for cash is stronger than industry lets on. But the second section – on implementation given the findings – seemed to fly in the face of the conclusions of the first section for me, namely don’t be over-confident and make sure you minimise fees and churn. The poor performance quoted on equities assumes a typical investor (lack of) strategy – but an index investor buying and holding would still do better than cash, which is all we really need to know. Buy and hold index investing entails its own risks, but it is the best option for most. Anything else, be it stock picking or timing, is likely to damage returns.

Personally, I think examining the case for cash against bonds would be more interesting, as these asset classes are typically used to preserve wealth rather than grow it. Would a low-cost bond portfolio e.g. 50/50 inflation-linked/long-dated UK gilts beat cash in an ISA, either in instant access or 5-year fixed accounts, after all fees? Enquiring minds would like to know!

Thanks to Pete and TI for the article & book.

All said, to argue that at an inflationary period the asset cash would do not as bad as equities, that’s a rather mind-shattering statement to me.

Perhaps the key here is inflation+strong bear market.

great reply rob—especialy PCA

mwap suggests timing the market

easier said than done—also when do you sell the market

Glad to see this post here, I think it is a good book and felt when I read it that it would be interesting to see it on Monevator.

Pete Comley has done a great job on this book which is certainly though provoking. It is very generous of him to give up so much of his time and effort for free.

Firstly can I thank you all for your feedback on my post. I’m a great believer in constructive criticism!

I have been away working (and what with exciting the football last night), this morning is the first opportunity I’ve had to read some of your comments. Let me take them one by one. Firstly I’m going to look at the issue of market timing.

One thing I did in my book was to always try to go back to source articles and really understand them. The key article here (according to Monevator’s 2009 article) is: http://www.marketwatch.com/story/survey-finds-sidelines-costly-when-market-turns-up?siteid=mktw

This is based on a press release issued in 2002 by a junior analyst working at SEI Investments. The original press release does not exist anymore and all we have a report based on it in Marketwatch which has been quoted hundreds of times by people since to back up market timing being futile.

Unless someone can provide me the full original survey results so I can verify what they did, I’m going to give you may take of how they probably got to those figures which so say justify their conclusion.

They state that if you’d held on to your stocks you’d have gained 32.5% in the first year of the recovery in the 12 bear markets from 1945 and 2002. Instead if you’d bought three months after the market turned you’d have made just 14.8%.

What this logic fails to present though is that, to have made the 32.5% you’d have needed to held your stocks during the preceding market decline of potentially 50% or more.

Therefore the true comparison is probably more like buy and holders still be doing down 10-30% after the first year of the recovery whilst those buying three months in being 14.8% up. This does not look like evidence against trying to time the market to me.

As I said, if someone can provide me the original source to critique, I’d be more than happy to potentially revise my view on it.

Regards

Pete

Pete

I agree that you are right to point our that the buy and hold strategy in the Marketwatch report would have suffered a substantial loss before the 32.5% rise.

Your comparison with the market timer being up 14.8% is only right though for the unusual investor who only ever makes a one off lump sum investment.

Most market timers will expect to nip out as well as in to the market. Clearly the market timer in this more common ‘out and in’ scenario will only be up 14.8% if they sold at the peak. More likely they missed the peak and associated rises by several months in which case they will be up quite a bit less than 14.8% and depending on figures (if they missed a lot of the rise) they may even be down more than the ‘buy and holder’.

I didn’t read the Marketwatch report as being unequivocal evidence in favour of buy and hold. I see it more as evidence of how accurate a market timer has to be with their timing not once of course but twice!

Glad to see your book is getting a lot of attention. I am still very grateful to you for demonstrating just how much portfolio turnover contributes to costs and how much survivorship bias flatters mutual fund tables.

Regards

Adrian

Adrian,

Thanks for the comment and follow up.

You are right to point out issues of people selling existing shares before buying back low. Their comparison will be different.

However I think the key issue has to be about new money. The finance industry mantra is to drip feed into your fund continually as that leads to the best outcome. Although this may be a good strategy in a secular bull market, it is not a wise one in the current secular bear market.

For this new (monthly) money, you might be better to be like a panther and store that up as cash in a pile and when the market puts in a serious low, pounce and buy stocks with all your accumulated cash at that point. That is what I’m advocating.

If you already have a portfolio built up over a period of time, and especially during the previous secular bull market, you are obviously better to just hold it through the market gyration.

But I still hold that the folklore that you can’t time the major gyrations of the market is not completely true. Interestingly, it is mainly perpetuated by those who stand to gain by you following that strategy. Also I’m not saying it is an easy strategy to follow, as the time when you have to buy will be one of downright fear and revulsion towards shares.

Pete

Thanks for coming back to follow up Pete. 🙂 I don’t want to intrude too much into the conversation here, but FWIW my view is that there’s a continuum between no market timing, a sort of ‘weak’ market timing, as advocated by Ben Graham (basically shift a little more between your allocations of fixed interest and equities, and never go all in either way) and a ‘strong’ form (trade in and out wholesale). I think the Graham-ish middle is more respectable. It seems clear that cash/gilts at 6% in 2000 should have been in most investors portfolios in a fairly decent slug, for instance.

A critic could argue this just replaces a demonstrably bad idea (wholesale market timing) with a more fuzzily bad one (i.e. you still lose returns only it’s not so obvious) but as I think psychological well-being is probably one of the major benefits of market timing (because people hate losses more than they love gains), ‘fuzzy’ may be no bad thing. 😉

I’d personally also have to take issue with a market timing system that doesn’t suggest a heavy equity weighting right now, with gilts yielding c.1.7% person, the 30-year yield around or even under 3%, and inflation making all that and cash less valuable over time, especially with cyclically-adjusted PE ratings and the like (for what they’re worth) suggesting the market is at worst fair valued. The only reason I can see not to favour equities is bad headlines, and they have a very bad track record of predicting future returns.

That’s not to say cash won’t do better. My main personal belief is nobody knows, you can only make an educated guess, and most should stay diversified.

(A lot of waffle for someone who didn’t mean to intrude. 🙂 )

” The finance industry mantra is to drip feed into your fund continually as that leads to the best outcome. Although this may be a good strategy in a secular bull market, it is not a wise one in the current secular bear market.”

This is because dumb money tends to have a better chance than clever money when it comes to market movements, mostly because the clever money often fails to be all that clever. The issue is when to buy – Sometimes there are clear moments in time when the market might move back up, say on the outbreak of a minor war, but most of the time you are unsure. Take investing in stocks now… many people have sold up and many more will sell up over Euro-zone fears, so you could argue that stocks are cheap, but then you have to assign a value to the cost of the Euro-zone problems, most notably in reduced bank lending to be sure across an entire stock market invested in a large number of different businesses. The question is when do you jump in – when Greece falls, a year after Greece falls, if Spain falls….? There are an immeasurable number of possibilities and scenarios to consider… all of which will be responded to by a market driven over-ridingly by irrational chemical impulses. All of this you must account for, accurately assess and then you must time an entry point that is reasonably near this irrational and unpredictable low point. You will undoubtedly miss the absolute lows and then if you want an exit point undoubtedly miss the absolute highs so 15% is your best bet and all this while the true disciples of Buffet, Fisher and Graham will find themselves earning at least 10% per year without breaking sweat once they have become sufficiently experienced.

If you can’t find businesses that are able to grow at 10% per annum then you have to really wonder whether you could time a market movement to perfection and also consider really whether it is going to pay off that well given all the effort. If you pull market timing off and make a mint out of it, then my next bit of advice to you would be to head to Vegas and carry out an Oceans 11 style robbery of all the big casinos. It might be interesting to document your progress in this, but most people who try market timing end up miserable.

We currently hold about 10% cash, mainly in NS&I linkers. The rest is fully invested but each pot (SIPPs, ISAs, etc.) tends to have about 2-5% cash.

My plan is to keep re-balancing, keep investing, and be grateful for the bargains that the market keeps throwing my way.

Pete

How do you know now that we are in secular bear market and how will you know three weeks on Tuesday that we still are?

For me that is the central question that a market timer has to answer.

I do think that Rob’s earlier comments that many of the reasons a private investor can’t stock pick apply to market timing too are very relevant.

Any way I have enjoyed the debate.

All the best

Adrian

Adrian,

Now we are starting to get a bit philosophical. How do I know we’re in a secular bear market? That is merely a description for a market which short term (ie multi-year not centuries but neither months) is trading sideways or down, of course. It has been doing this since 2000.

No one can tell you what it will be in 3 weeks time.

However, personally I think that there is something in history rhyming. Moreover the bigger the pattern (over multi-years) and involving more stocks (ie on an worldwide index level), the greater the potential predictability aka Issac Asmov’s psychohistory concept – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychohistory_(fictional).

Given this, individual stock picking is going to be more difficult than predicting the broad direction of the world equity index (inc FTSE). That is not helped of course because so much of the variance of an individual’s shares price is determined by market sentiment.

I guess only time will tell which of the two scenarios I predict in my post happens first ie FTSE 4000 or 7000. I still stick by thinking that whichever of them happens will be followed by a high probability of a marked capital appreciation of the FTSE in the following years. In contrast if I invest today, there is potentially an equal probability of the FTSE being higher or lower in say 2 years time. It is therefore just a mathematical calculation in my head of most likely gain x probability.

Like you (and all the others on this thread), I think this is a very interesting debate. I may well be wrong (as I feel in a distinct minority!), but we’re all wiser for challenging our ideas and being forced to try to justify them.

Regards

Pete

How about this line of thinking. If we’re waiting for the FTSE to hit 4000 or 7000, we have three entry points; 5500 (i.e. today), 4000 and 7000.

This means we have two choices:

1. Invest now and get a 27% return when the market reaches 7000, which I assume it inevitably will at some point.

2. Take a bet on making a 75% return from 4000 to 7000, or a 0% return when the market reaches 7000 if you get in at 7000.

This means that you’d have to think the odds of the market reaching 4000 were better than about 36% (27/75) for the bet to be at least as profitable as getting in at 5,500 today (I guess there’s a little bit of fudging relating to discount rates and yields etc while we’re waiting for the market to get to 7000, but they can stay under the carpet for now).

I suppose the only way to make a guesstimate over the odds of the market reaching 4000 would be to look at something like the Shiller data on valuations in the US and see how often the markets tend to reach a valuation like the one we’d see if the FTSE reached 4000, given the level of earnings power (for PE10 etc) we currently have.

I guess that wouldn’t be too hard to work out with a bit of time and a spreadsheet, but how well it related to reality would be a different matter.

I do think something like that would be worth doing before leaping into a 4000 / 7000 market timing bet, otherwise it’s little more than a punt at the casino. It might turn out that, statistically and historically, it is actually a fair bet to take.

I’ll leave it to any resident statisticians to poke holes in that.

I promised to reply on some of the issues/comments made. Again thanks to all who raised them.

@ John – thanks for attempting to quantify my logic in a”back of an envelope” style. That is really useful. I’ll try and do it a bit more properly when I get a mo.

@David/Paul – Just to clarify that chart definitely is without dividends (and I’ve checked the data). I chose it because it is showing what is effectively the FTSE index (we all use day in, day out) but allowing for inflation. What it helps clearly demonstrate, in my view, is how important dividends are (ie they are normally pretty much all of your return).

@ Rob – You question if I’m right to highlight that DB study. Firstly DB are not the only people to suggest that – in the book I mention for example that Barclays Mortgage dept now assume that anyone using a stock ISA over the next 25 years is only going to get a return of the cash they pay in.

So why did I focus in on these when so many others say life is going to be rosier? I’ve been a market researcher for 30+ years and spend my time trawling data for weak signals that I think are significant. That is what I’m paid to do. This one triangulates with all the data about the ever growing size of our debts and so I think it could be important. Again, as I’ve said before on other issues, I may well be proved to be wrong. It is just a gut instinct about it for me.

Regards

Pete

Pete,

Well argued and well reasoned strategy that stands up on its own merit.

We all know the old adage about statistics and I’m surprised that some feel obliged to challenge your deconstruction of this particular statistic as it blatently supports your argument.

Utimately it’s all about confidence or fear if you like and buyers remorse is just as stinging as sellers remorse. The theme of this blog is passive investing and thus shouldn’t need any further comment as it has it’s own track record to support it as a strategy. There are many strategies out there and who can say if they’re worse or better in three weeks time, they’re certainly different if we feel the need to say something.

I’ve just thought of a new one “Passive investing for a pin owning Monkey” I may put it to the test, soon………. 🙂

I’ve tried market timing with mixed success, getting out of equities in Jan 2008 to miss the worst of the falls, then being overly defensive and not getting back in quick enough in 2009.

However my worst decision was selling out last summer and crystalising losses at what I now believe will be a floor (FTSE 4800-4900) barring a global depression.

Nope, the way forward for me is to keep pound cost averaging through thick and thin and keep a larger % in index linked gilts and cash than I previously did to suit my risk profile, which is something Tim Hale discusses well.

This is much easier to do with an ISA portfolio where you can get 4% on (2 yr fix) Cash ISAs without the downside risk of gilts to capital value, but tougher within SIPPs when you are loath to leave cash there earning 0%. A need to view a portfolio across all wrappers perhaps?

You talk a lot of sense, even though you say that holding cash at the moment is a bad thing but investing into equities is even worse. At the end of the day we can only make decisions on the information to hand and the opportunities available. The only other option is to keep the cash in the attic or under the bed, which is even worse. Therefore better to say that cash is the best option at the moment. Also, a lot of the decisions we make are based upon the outcome we perceive to be the most likely.

Forgetting all of the economic issues around the globe, which I am sure no-one fully understands, the average saver or investor is short on both information and options. No-one fully understands the issues and I personally believe there is still far too much that is yet unknown. I agree that printing more money is a dangerous game and the risks of hyper inflation are closer than we like to believe.

The problem is that politicians around the world are driven by attitudes of voters and to keep the votes coming in they keep feeding un-founded useless messages about the potential growth in the economy, whilst staving off the real threat of recession with even more capital injections. As this policy becomes more typical, more money will continue to be printed and since they have become used to managing from crisis to crisis, they will not change their behaviour until the crisis hits, which in my view, as yours, is inflation.

So what to do?

You are right with your views on cash and how you seem to be managing your money. To manage cash effectively you need to have a plan.

My plan operates around the following 5 principles:

1. Protect your capital.

2. Make a financial decision every year. (Do not allow your savings to be spread over too many accounts because it can easily become over whelming)

3. Save for the longer term. (The best rates are available on 5 year fixed term account. Structure your savings so that you can roll your money over into a new 5 year account as each existing account matures. But always have sufficient money accessible)

4. Do not be over-loyal to any bank or building society. As you put it – become a rate tart.

5. Utilise the full protection of the FSCS to make sure every penny is protected. We have no idea which banks are yet to fail!

Good to hear so much intelligent debate on this subject on one page.

I’m relieved to hear the likes of Pete Comley defending a case for cash for a change.

Why is it that individuals like me are constantly told by industry professionals not to hold cash, not to buy property, gold, land etc. – always types of asset that don’t benefit their industry (even though many of the funds they then put our money into actually include those assets) ?

Based on Barclays Equity Gilt Study data, if you consider cash to be a ‘stock’ whose share price remains the same (zero capital gain or loss in nominal terms) and that pays a ‘dividend’ (interest), that you might either spend or reinvest, then when compared to stocks, cash beat stocks in 39% of years since 1900 (i.e. stock prices declined) and cash on average paid a higher dividend (gross cash interest averaged 6.5% compared to average 4.5% stock dividend yield).

Where cash falls short when compared to stocks is in years when stocks provide strong gains. Whilst the worst half of years for stocks averaged -8.5% less than cash’s 0% capital gain, the best half of years for stocks averaged +20% (price only changes).

70% exposure to -8.2% and 30% exposure to +20% = 0% overall. If you allocate 30% to stocks, 70% to cash, its perhaps not as bad an investment as many might have you believe. Especially if you look to use low cost/low tax options. BRK-B for instance, 15% allocation has low expenses once bought and pays no dividends so there’s no US withholding taxes applied against UK investors, there’s also 15% FX (USD/GBP currency movements) wrapped up under that umbrella, as well as being a holding company that holds many other stocks (somewhat index like). FT250 is akin to a small cap value index and a 15% allocation to that will incur a 0.4% expense if held via MIDD.L, or less if held via HSBC. Tax harvest stock gains using yearly CGT allowances and hold ‘cash’ in a ISA’d 5 year gilt ladder and/or National Savings Index Linked Gilts etc. and MIDD.L expenses might be the only costs for the portfolio (excepting some share/gilt trading costs).

In GBP terms the worst year since 1986 was in 2008 when such a portfolio declined -2.8%. Since 1986 the portfolio averaged 6.9% real annualised (10.7% nominal annualised). Last year up 9.5%, year to date 2013 up 10% http://tinyurl.com/qbqglsg

[Note that the above Clive’s Lazy Portfolio for UK investors 🙂 assumes each gilt is held to maturity and as such interim capital price fluctuations in gilts are ignored. A 5 year gilt ladders yearly gains are then typically just the average of the current and past four years 5-year-gilt yields]

The only cash ISA’s that offer a competitive rate in comparison to inflation they seem to want to lock you in for 3/4/5 years in order to get a decent rate. Is this wise when interest rates and subsequently the cash ISAs rate will increase?

I was setting up my portfolio today. I stumbled into a cash fund from Blackrock. Can anyone clarify the purpose of these funds?

DOW—15 June 2012

12767

DOW—7 Feb 2014

15794

+23%

I don’t think you can time the market, cash or equities

Well, I don’t think the author Pete Comley can on this evidence (but it is only one piece of evidence).

Remember this is a guest post. 🙂

As I discussed at the time (and in other posts) the logic of calling for cash at that point seemed stretched. I thought he made a good case for cash as part of asset allocation, and for index trackers, and also for saying that most private investors can’t — as you say — call markets.

Which made his final conclusion that he was going to sit in cash rather perplexing to me.

Still, who knows, it might have all gone differently. Always have to remember the counterfactuals.

Interesting discussion and debate.

As I wrote in the conclusion of the original article, I saw two potential scenarios. One was that major indices would put in another low (in which case the cash would be useful). The other was that when they reached the top of the trading range they broke out upwards. Even though the FTSE has not done that, I think the evidence from the S&P is that it is this scenario that has played out.

Indeed I started dripping my cash into the market a while ago. Although I have missed out on some of the rise in the last year or so, I am more confident now that we’re at the start of the next secular bull market, so the downside risk is much lower.

Over cash more generally, a lot has changed over the last two years since I wrote that article. Financial repression from governments squeezing cash even more with its yields even lower – almost a half of what I was quoting. Moreover my current guess is that central bankers will keep their strangle hold over low rates for a good many years to come.

Therefore if I was to write this article again today, I’m guessing it may be quite different in a number of key ways.

Pete

isa cash saving rates also slashed last few years

DOW–1 sept-2014

17098

Firstly, why am I so negative about the coming years?

that’s calling the market?which you proved cant be done over longterm

As bank accounts are insured by the government up to a certain level but uninsured above that level (£80k I believe) does it not therefore follow that cash deposits are in a sense subsidised by the government up to £80k? If this is so, does that not therefore make bank accounts the best investment overall on a purely risk adjusted basis (for the small investor)? No other asset class attracts a subsidy in this way (except perhaps VCTs through the tax credit)