For someone like me from a pretty normal lower-middle class background, buying shares, bonds, and other assets once seemed about as relevant as joining the Freemasons.

I used to watch the prices on TV before starting my paper round as a kid, when I’d guess which ones would go up and down by tomorrow. I was reading the business section of the newspaper before university.

But actually dealing directly in shares? I’m not sure I even knew it was possible.

If you’d asked me, I’d probably have said it was something chaps from public school did in the City of London, having joined a club with handshakes and secret whistles and getting red braces with their membership card.

I was wrong to think it was that exclusive. Investing in shares was already being done by tens of thousands of ordinary people using a stockbroker, and by some brave souls using an execution-only service over the telephone.

Millions in the UK also owned shares thanks to Margaret Thatcher’s privatisations of the giant state-run utilities in the 1980s, and the demutualisation of building societies in the early 1990s.

But few such people would have called themselves share traders. Most had the certificates showing they owned a stake in one or two companies stuffed at the back of their filing cabinets.

In terms of day-to-day life, those share certificates were about as relevant as their old Scouts and Guides certificates on the wall.

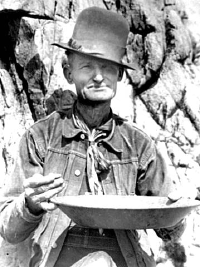

The gold rush that taught us how to trade shares online

The dotcom boom of the late 1990s changed everything. Not only did buying and selling shares in companies like eBay, Autonomy, Amazon, Marconi and a host of now-forgotten tech outfits turn investing into an extreme sport for 20-something desk jockeys, making and taking away fortunes in the process. The Internet also provided the tools required to play the game.

With a PC wired up to the Web (yes, you still needed wires back then) and an account with an execution-only online broker, anybody could – in theory at least – buy shares toe-to-toe with the professionals.

One famous eTrade advert captured the zeitgeist by portraying a truck driver who reputedly day traded from his cab. Old City of London brokers would have turned in their graves (if there’d been a profit in it).

When I think back to those times, it seems scarcely believable it was just a decade ago.

I regularly visited San Francisco and L.A. for work, and the airport shops were full of books about local (if often recently arrived) boys and girls made good, who half the incomers on the plane wanted to emulate. Several friends left the UK to join Silicon Valley’s ecosystem and never returned, although none hit the big time.

One personal standout moment was when a vague friend – a banker who is now a senior Vice President in one of the biggest City names – urged me to give him a call if I launched one of my mooted dotcom start-ups.

I was young-ish, had hung around technology most of my life, and knew people who did exciting-sounding media things. What’s more, I always had opinions and ideas.

As my acquaintance knew, that was quite literally enough to land you millions of dollars in investment in those strange times, as long as you didn’t think too hard about how you were going to make money. (This was where I always came up short.)

Once you had your Internet venture underway, anything could happen. The banker, already on his way to millions, wanted skin in this game.

From wage slaves to company owners

Even if you didn’t aspire to found the next Netscape – the first such super-success story – you could still be touched by the dotcom boom.

One company where I was among the launch team lost its sales manager within six months after he declared he’d made so much from share trading that he was cashing in his winnings to open a diving school somewhere hot. I don’t know if his business prospered; the point is that he could afford to retire before he was 30 and having never earned a silly salary – all on the proceeds of technology share trading.

Another former employer got a stock market listing and all the staff – mostly on meagre salaries and only on their first or second jobs from college – were granted a generous allocation of shares. Sadly I’d left before then.

Visiting an old friend at the company, I was amazed to see that many of these formerly artistic types, from the secretaries to my friend in management – now had shortcuts to stock tickers on their desktops.

They were entranced to see themselves become richer by the day (shares in this sort of company didn’t go down much in 1999) and they watched their share prices like parents cooing over a new baby.

Share trading after the dotcom boom turned to bust

Very few of my former workmates sold their shares, and as a result the dotcom crash left them much worse off. The stock tickers left the screens when the price fell by more than 90% from their peak.

Next to go were the office flowers and plants that were being supplied by a third-party on contract, then the fancier offices, and then freelancers like me. Finally their jobs started going, too.

I admit I’d been jealous when I saw the windfall shares my former workmates had been granted – I didn’t begrudge them a piece of the action, but I wished I’d been so lucky. Naturally I was now grateful I’d avoided the whole debacle.

But I did have some near scrapes with the dotcom boom and bust. For a start, I spent too much time dreaming up those dotcom ideas that I never went through with. One might have been a whopper, as fishermen say of the ones that get away. My career went a little haywire in the meantime. Only myself to blame.

More importantly, I almost opened my first ISA in 2000 in March, just days before the dotcoms began their death plunge.

Still knowing little about the stock market, I used an online fund supermarket to select a fund relevant for my age and risk profile. It suggested the Henderson Technology Trust, presumably on the grounds that I was too young to deserve any money I’d saved up – so what the hell if I lost it?

I knew nothing, really, about diversification, let alone averaging into the market, nor did I have more than a vague sense from my general reading that the market might be expensive.

The truth is that in 2000, not being invested in technology or having options in your dotcom employer meant you felt you were being left behind every day.

Luckily I was younger and more pre-occupied with my work that then took me around the world – and even with the odd party in-between – than with using my ISA allowance.

So I never got around to putting the money in, at what would have been the peak of the market, almost to the day, and I thus saved myself several thousand pounds in the peak-to-trough fall in the Trust that followed.

Emerging from the wreckage

As well as making share trading accessible to everyone including me, the dotcom boom and bust helped instil in me a fascination with the markets and investing that endures to this day.

At the peak on December 30th 1999, the FTSE 100 hit a P/E ratio of 30, despite its relatively low weighting of tech stocks and the fact that shares in so-called Old Economy shares had been falling for months already.

Yet rather than see the market as expensive after a ten-year boom, otherwise sensible people saw it as cheap. How and why they reached this conclusion fascinates me – and I think of it often when I too warn against being too pessimistic about the market.

I don’t believe anyone can predict the market even over the medium term, although I do think you can play probabilities – but I really don’t want to be writing the liner notes for the next bear market.

Many people swore they’d never invest again after the dotcom crash, but personally I became addicted to online investing forums after thankfully arriving too late for the party.

It was particularly fascinating reading the tales of lost fortunes from people writing in 2000 and 2001 as their holdings fell. Buy on the dips, they said. Most who clung on lost nearly everything, but they kept believing until the end.

Luckily I didn’t start putting money into the stock market until the dust had settled; perhaps jumpy from the recent crash in shares, I was overly pessimistic about the UK housing market (I still think it’s overvalued!) and decided to invest my money in shares instead.

Ten years on I now own shares in the Polar Capital Trust – the Henderson Trust as was, renamed after the dotcom crash.

I picked them up earlier this year with an eye on all the cash that the big U.S. tech giants have ferreted away. Polar Capital is up over 50% and I’m happy to keep holding, if only to make up for the UK market’s under-weighting of the sector.

But I also suspect we’re due another technology boom in the next few years. And I feel rather better placed and far more well-informed to profit from this one.

Note: The title of this post is a play on Jesse Livermore’s barely-disguised biography, Reminiscences of a Stock Market Operator. It’s well worth a read, whether you buy it from Amazon UK or Amazon US

.

Comments on this entry are closed.

You should stop by San Francisco again. It’s absolutely nuts out here how bullish everybody is!

Homegrown Linked-in is now worth $1 billion, Facebook is probably going to go public over the next 13 months with a valuation of $10 billion. They’re also based here. Meanwhile, Twitter is right in the heart of downtown San Fran as well and they’re doing well.

There’s so much money out here, I don’t understand why everybody wouldn’t want to move here to network and try and make it big. The Venture Capitalists are a bumping!

Cheers,

Sam-urai

@FS: “Facebook is probably going to go public over the next 13 months with a valuation of $10 billion”.

Roll on to 2021 and FB (now rechristened Meta) hit $1 tn cap, 100x the $10 bn IPO being salivated about in 2009.

2022 saw it fall nearly 80% peak to trough before staging no less than a 178% bounce back in 2023.

Just about anything can happen out there in the markets, and the longer the horizons the more scope for craziness both to the upside and to the down.

Case in point: ~ a decade ago the 7 biggest tech stocks were collectively capitalised at $1.5 tn. Now they’re at $12 tn, which is bigger than the combined caps of the stock markets of Japan, China, France and the UK.

If there’s a lesson in there, then I’d venture that it’s along the the lines that just because something sounds nuts doesn’t necessarily mean that it can’t happen.