Just as one of the most dangerous phrases you can hear in investing is…

“This time it’s different.”

…one of the least profitable things you can utter to yourself is:

“I’ll never touch that again.”

Let me qualify that. The investing world does have its untouchables – not in the Prohibition Agent Eliot Ness sense, but in the old Hindu caste system sense, in that you should ready your bargepole at the first sniff of them.

I’m thinking of expensive managed funds, initial and trail fees paid to financial advisers, structured products you don’t understand, and opaque long-term vehicles that lock away your money for a few decades before returning it (assuming the managers haven’t squandered the lot in-between) – all radioactive from an investing standpoint.

Moreover, in today’s low interest rate era, anything offering 10-15% a year like clockwork is either a Ponzi scheme or you don’t properly understand the risks.

Nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so

Away from those perennial nasties, however, there’s a time and a place for most investments.

In particular, when it comes to asset classes and out-of-favour strategies, yesteryear’s irrational exuberance is often tomorrow’s post-crash bargain.

Obviously I am speaking mainly to more active investors here. If you’re a purely passive investor, then you may consider that even pondering these gyrations is beyond the pale . More power to you, but for those of us who stray from the true path, to quote Ecclesiastes III and The Byrds:

“To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven.”

House rules

Let me illustrate the point with something everyone can relate to: residential housing. At the time of writing, barely a week goes by without some American columnist proclaiming they’d never be so stupid as to buy a house in America again. The whole consumer economy there is mired in the doldrums as a result, despite already significant house price falls.

US websites have ran countless articles this year on why housing is a terrible investment, and how it will remain so for generations. In one piece entitled Attention America: We are terrible homebuyers, the Motley Fool’s author writes:

Fact: It’s a crapshoot whether most people make money on the purchase of their home.

The real fact is that’s not something you heard much in the run up to 2006.

Even when I began Monevator, I regularly heard that America was immune to a nationwide property crash. Another fact: Nearly everyone only wakes up to the downside of any risky investment after the slump, and then they go overboard trying to understand what hit them, as if it will belatedly protect them.

Some articles do dig deeper: One good New York Times piece I read recently has a useful table of rent-versus-buy comparisons across various American cities.

But others express sincerely held views that I suspect only find a wider audience because of the tenor of the times, such as hedge fund manager and infuriatingly great writer James Altucher’s Why I Would Rather Shoot Myself In The Head Than Own A Home.

Recent event syndrome

The plain reason why US publications are filled with articles extolling the carefree benefits of renting are summed up by this graph from The Big Picture blog, which updates Robert Shiller’s legendary graph of US home values in real terms:

(Click to enlarge)

After the bubble must come the bust. Prices may not have completely bottomed, but another boom is surely just around the corner, if your time perspective is long enough.

Unlike American house prices, which until recently were flat for many decades in real terms, UK house prices have shown modest but meaningful real growth over time. Blame the small island effect.

Yet this doesn’t justify any old price for a two-bed terrace – and these small real gains also underwrite one of the most volatile housing markets in the developed world.

Check out this graph of real UK house prices from Economics Help:

Life is a rollercoaster, if you're a house price index.

The graph runs until summer 2007; I have left filling in the sharp lurch down that began later that year as an exercise for the reader.

But now look back to the trough of 1995; in real terms house prices were approaching half their 1989 peak. I was newly-graduated in those days, and I can well remember reading articles explaining that my rootless generation would never buy again, but would instead holiday for months in Thailand and telecommute (as it was called then) from Berlin.

In reality of course the journalists were trying to put a plausible story on an age-old cycle – few had any inkling that the greatest house price bubble the UK has ever seen and the birth of buy-to-let mania were just around the corner.

The lesson? It’s safer to trust the graphs, the numbers, and reversion to the mean than any fanciful macro-economic theories.

The main boom-to-bust cycles

I’ve labored the point with house prices because nearly everyone knows they move from boom to bust with some regularity, even if timing the shifts can make an idiot out of even the smartest of us (he says, having been calling the top of London property prices since 2004…)

But you get these waves in most assets, driven by deep and recurrent cycles:

The inventory cycle – Companies expand as business booms until they’ve got too much stock (/materials), then halt new orders, which hits their suppliers, shakes out weaker ones, causes a downturn, and so on.

Capital spending – Like the inventory cycle, only slower to unfold because it costs more to build new factories or oil wells than it does to make more widgets – and therefore it’s more expensive and protracted when it blows up.

The business cycle – There is a clear pattern to how economic expansion and contraction ripples through different segments of the economy, related in the crudest form to how we first get raw goods out of the ground and eventually turn the value into iPhone-wielding designer clad hairdressers.

The property cycle – As detailed in the graphs above, this is intimately linked to…

The credit cycle – Banks move from hyper-cautious to carefree with money, increasing the extent of their loans over many years even as the quality of those loans deteriorates. The buck invariably stops with an over-priced semi at Number 23 Acacia Avenue, and/or Number 1 Canary Wharf. The downswing of a credit cycle can be hugely painful, as we’re experiencing as I write.

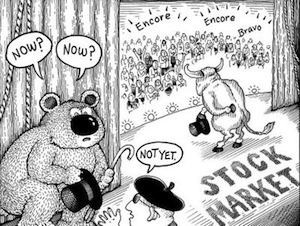

Investor sentiment cycles – Investors move from fear to greed as they remember and forget the risks inherent in different asset classes. Sometimes investor cycles proceed in tandem with the cycles above, other times investors have a mind of their own. They’re perhaps linked to demographic cycles, that see new generations of inexperienced professional money managers take the place of seasoned veterans put out to pasture.

These are my off-the-cuff terms, and they may differ from the textbooks. But the basic point should be clear – more often than not, the downturn is something we’ve seen a dozen times before, and yes, there will be an upturn. Yet in the midst of that slide down, you won’t be able to open a newspaper or click on a blog post without reading that some new and invariably grim reality is afoot.

Cycles in asset classes

Let’s consider a few more examples of how these wider cycles have been manifested in investing terms.

Commercial property from 2007 to 2011

In early 2007, commercial property was yielding less than you could get from risk-free cash on deposit. Madness. After the credit crunch, owning and letting out an office was considered akin to base jumping or shark wrestling in terms of riskiness. Yet it was hugely unlikely that the biggest real estate companies would never see their prime properties come back in fashion. Accordingly, I was buying commercial property in summer 2009. The property ETF I mentioned in that piece is up nearly 42% since then.

Oil explorers since the late 1990s

In 1999, The Economist famously published a piece arguing oil would remain at around $10 a barrel for the foreseeable future. It wasn’t a particularly contrary view – that was the prevailing wisdom in an era when the future was digital and energy intensity was declining in the West. Needless to say oil subsequently boomed in the next decade as the emerging markets, well, emerged, reaching $145 in 2008 before being knocked back by global recession. Innumerable small cap oil companies spiraled up with it. A typical winner (there were plenty of losers, too), which I held for a stint, was Soco International, which rose 4,900% between that Economist article’s publication year of 1999 and mid-2007.

The gold price

After a huge rally in the late 1970s, the gold price broke through $800 in 1980. Finally miners were convinced the demand for gold was here to stay, and ramped up investment and production (see the cycles above), which only helped usher in a 20-year bear market in the metal. Gold declined in value year-after-year, contrary to claims that it was a great inflation hedge. It took our own former prime minister Gordon Brown to inadvertently signal the bottom for the slump when he flogged off more than half the UK’s reserves at prices between $256 and $296 an ounce. As I write, gold is back above $1,500.

Tech shares AFTER the dotcom crash

You’d have to be a mug to ever touch tech shares after the dotcom slump, right? No, you just had to be patient. After most investors had sold out and innumerable tech funds and investment trusts had been shut down, the handful of survivors began rebuilding again from the bargain basement. Herald Investment Trust, for instance, is up 178% since the start of 2003 (around the bottom of the dotcom slump) compared to a mere 53% rise in the FTSE 100. Not bad given there’s been a second bear market in between then and now. Some individual tech shares, such as ARM and Autonomy, have done magnificently.

Cowardice will cost you dear

The takeaway is that being an active investor and trying to time markets is dangerous, but being a permanently bearish active investor is even worse – perhaps even worse than being perma-bullish. After all, stocks and most asset classes (though not most commodities) tend to go up over time.

Poor timing will decimate your returns. When I looked at strategies for investing in bear markets, I shared some telling results from a study of 12 post-World War II bear markets that stand repeating:

- Investors who held their shares through the bear market gained an average of 32.5% during the first year of recovery.

- Investors who bought one week after the market rally began saw a 24.3% return.

- Those who waited for three months before jumping back in achieved only 14.8%.

These are enormous differences – and in reality, many investors won’t have even bought shares again after three months!

For shares, read whatever spurned asset class you care to mention. The best time to buy is after an almighty crash, when everyone is telling you you’re an idiot, yet you can still see a future for the asset or sector. Yet most people do the opposite, timing their purchases with stunning incompetence.

For example, one recent study found the US S&P 500 market has returned 8.4% a year, but the average US investor has earned just 1.9%! The enormous gap is due in large part to their terrible timing decisions.

I’m not saying that you should leap into any old share or market sector that has wobbled recently. As I write, for example, many energy and commodity shares are down about 10% on worries about China. That’s not a rollercoaster, that’s a speed bump.

But when an asset class is really unloved, and really in the doldrums, and screaming that it’s going cheap – think ‘this too shall pass’.

To conclude, I couldn’t help smiling when Warren Buffett declared he was buying the Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroad company in late 2009. That’s one industry that’s been written off more times than Madonna, and yet it keeps on coming back.

When Buffett slapped down $34 billion to buy all the outstanding shares in the train freight giant, was he worrying about the railroad stock mania of many generations before that was the dotcom equivalent of its day? Was he thinking the US and its consumers were mired in recession and therefore always would be?

No, he was thinking it looked cheap for the long-term. And so he bought it.