The 4% rule went viral because it was billed as simple and safe (*coughs a noise that rhymes with bullwhip*).

The 4% rule went viral because it was billed as simple and safe (*coughs a noise that rhymes with bullwhip*).

Unfortunately, the 4% rule is not safe.

Nor is it simple, once you put the nuance back.

The story is seductive – that you can withdraw 4% a year from your portfolio and never run out of money.

This is often known as a safe withdrawal rate (SWR). Unfortunately the 4% version is about as reliable as that other withdrawal method you’ve heard of.

Got a portfolio of £1 million? The 4% rule claims you can safely withdraw £40,000 in year one, adjust that amount by inflation in year two, and so on, every year until the happy hereafter.

The 4% rule also gives us the rule of 25. Want to live the life of Reilly on £40,000 a year?

£40,000 x 25 = £1 million

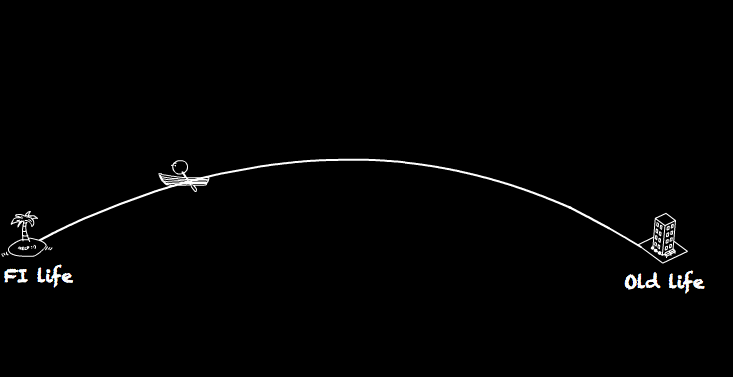

That’s the sum you need to amass before you can hit the beach.

Simple as that. At a stroke of the calculator anyone grappling with a defined contribution pension can treat it like it’s one of those turnkey defined benefit, gold-plated jobs!

If only.

The 4% rule: the things they forgot to tell you

Where to begin?

The 4% rule doesn’t include taxes. The £40,000 figure above is gross income. You’ll need to live on less after tax.

Worse: the investment growth assumptions that underwrite the rule assume no capital gains, dividend or interest taxes. If your investments aren’t completely shielded from tax then you’ll need to lower your SWR.

The 4% rule doesn’t include investment costs. Fund charges and platform fees chip away at your annual returns and leech the SWR. Financial planner and researcher Michael Kitces explains that the answer isn’t as simple as deducting your portfolio’s total OCF from the SWR either.

(Another thing to note: the 4% rule reinvests dividends. If yours are spent or taxed then fuhgeddaboudit.)

The 4% rule applies to 30-year retirements. If you live longer than 30 years then the failure rate creeps up unless your SWR goes down.

Financial planner William Bengen, whose research inspired the 4% rule, recommended a 3% SWR to see you through 50 years or more.

The 4% rule uses US historical returns. Bengen’s original portfolio comprised:

- 50% US equities

- 50% US intermediate government bonds.

Bengen then used historical annual returns from 1926 onwards to discover that an initial withdrawal of 4% would have enabled retirees to live out the next 30 years on a constant, inflation-adjusted income, without running out of money, come hell or Great Depression.

That’s nice, but remember the US enjoyed super-powered investment returns during the period studied. Other developed countries did not fair so well. Retirement researcher Wade Pfau calculates:

- The UK’s SWR as 3.36%

- Germany’s as 1.01%

- Japan’s as 0.27%.

- Even the global portfolio only made 3.45%

Apply the 4% rule to Japan and your money ran out one third of the time. In the worst case, your money evaporated in just three years!

Pfau and others even doubt that Americans can rely on future returns being so kind.

Known safe withdrawal rates will fall if a future sequence of returns is worse than anything currently stinking up the historical record.

What can you do with that information? Well, some researchers have worked on the link between current asset valuations and SWR. You’re advised to choose a more conservative SWR when valuations are high, while you can live a little when valuations are low.

Incidentally, the 4% rule even fails in the US when you use a different dataset. Many retirement researchers argue that the sample sizes are too small anyway.

The 4% rule applies to a specific asset allocation. Change the 50-50 US equities and intermediate government bonds split and you’re playing a different game. Bond heavy portfolios (say over 65% bonds) have historically sustained lower SWRs, especially over longer time horizons.

Sticking with allocation, UK investors shouldn’t use US SWRs – but you should appreciate that UK SWRs aren’t appropriate either if you’ve got a globally diversified portfolio.

Bengen and others have shown that diversifying into certain risk factors can improve your SWR. What about other assets such as REITs or gold? Will they improve your chances? The future is uncertain.

The 4% rule’s definition of success is probably not yours. Some SWR studies apply a sneaky ‘success’ rate. They count a SWR as sustainable if it only failed 5% or 10% of the time. The famed Trinity study did this. I think this is acceptable, but you may not. Either way it’s not ‘safe’.

Failure itself is defined as people running out of money before they run out of time. You spent your last dollar as you expired on the final stroke of midnight, December 31st, on the 30th year of your retirement? You’re a success baby!

This definition of failure keeps things simple but it’s not realistic. Most people aren’t oblivious to plummeting portfolios. They won’t fling themselves off the cliff edge like an Olympic lemming. Many will slow down their spending before it becomes unsustainable. People also cut spending in scenarios where the situation looks dire but hindsight tells us things ultimately worked out just fine.

Sadly, you don’t know which it is at the time. People cutback early because they can’t predict if they are history in the making, or whether they’re living through just another close shave for the 4% rule. In other words, living the rule can be pretty scary without a Plan B.

The 4% rule is inflexible. What if you need to spend more than your SWR allows? I don’t mean you have the occasional bad year. I mean something changes that proves your original income estimate to be off-base. Maybe you have unforeseen health costs, or a newly dependent family member. Perhaps there’s no obvious lifestyle creep but your personal inflation rate constantly outstrips headline inflation. Within five to ten years you’re spending way more than planned.

A high SWR like 4% gives you little room for manoeuvre when high spending meets poor returns. Everybody needs a more flexible plan than the basic 4% package suggests.

What if you spend too little? The selling point of a SWR is that it’s supposed to survive the nightmare scenarios. If life turns out better for you – and most of the time it does – then you could have spent more before you were gonged off. All the other caveats notwithstanding, Kitces shows that the 4% rule typically does leave large sums of spare lolly on the table.

Now that’s a good problem to have, especially for your heirs. Whereas, if you definitely want to leave something for your heirs, well, that’s not the 4% rule’s bag. It assumes capital depletion is A-OK. If it’s not then you’re into the expensive world of capital preservation.

So, you can spend too much or too little! Which is it? Well, naive application of the 4% rule can lead to either. It’s a rule of thumb not a strategy.

None of this is meant to impugn Bengen’s original research. It was groundbreaking and he clearly flagged his assumptions back in 1994. The 4% rule has taken on a life of its own, whereas Bengen’s work was only meant to be part of the puzzle. What’s often missed is the advances made in retirement research since.

You can devise a strategy from the wider body of knowledge. See McClung and also our post on how to work out a more sustainable withdrawal rate.

Step one is understanding that living off your money is as much art as science. And step two is knowing that the 4% rule does not work as popularly advertised.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

Bonus appendix: 4% rule maths

Year 1 income: Withdraw 4% of your starting portfolio value.

500,000 x 0.04 = £20,000 annual income

Year 2 income: Adjust last year’s income by year 1’s inflation rate (e.g. 3%):

£20,000 x 1.03 = £20,600

The 4% SWR only applies to your first withdrawal. Every year after you withdraw the same income as year 1, adjusted for inflation, regardless of the percentage that removes from your portfolio.

Year 3 income: Adjust last year’s income by year 2’s inflation rate (e.g. 2%):

£20,600 x 1.02 = £21,012

And so on. Until the end. Which this is. At least it feels like it.