Who needs to make back-up plans when you’ve spent a decade writing about and otherwise pondering living off a portfolio in (early) retirement?

Surely I’ve thought of everything!

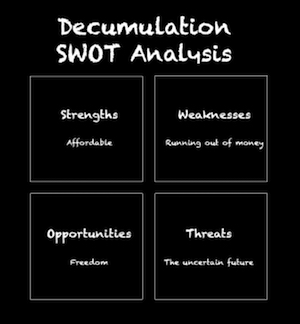

I mean, in part one of this series I outlined my decumulation plan in excruciating detail.

And part two saw me thrill you with an explanation of how I’ll use a dynamic system to manage my asset allocation and determine what we can withdraw to live on each year.

In short, I’ve put more thought into this than anything in my life before.

But what if I’ve miscalculated? Or what if we face market conditions that out-disaster any historical catastrophe?

Then we’re fu-

…then we’ll turn to Plan B.

My A-F of back-up plans

The ultimate plan B in decumulation is our house.

The Investor convinced me years ago that it’s rational to think of your house as an asset, even though that’s difficult emotionally.

If I really have to, I can convert my home’s estimated sale price into X years rental income, or X months in a care home.

Alternatively, it could provide an income injection via equity release.

We have other back-up plans, too.

Our State Pensions and Mrs A’s small DB pension are Plan C. These don’t come on stream for years but I haven’t included them in our SWR, so they’ll be a bonus when they do.

Plan D is working for money from time to time.

I want the option of never needing to work again. That doesn’t amount to a religious vow never to work again.

I’m happy to work on projects I think will be challenging in an enjoyable way. I just want the freedom to choose, and to walk away if need be.

Mrs Accumulator will also maintain part-time hours for now.

It’s good that we’re both keeping our hand in to some extent. Even a small amount of income takes huge pressure off our portfolio in the early years. This reduces the chance of us being forced back into the labour force from a position of weakness.

Plan E is annuities. At some point in our seventies there’s a good chance the mortality credits will make them a worthwhile hedge against longevity risk and portfolio volatility.

Annuities get a bad press. They make people bristle psychologically. Near-zero interest rates don’t help, but annuities are still a useful tool if you’ve got a long lifeline.

On that tip, Professor Moshe Milevsky, who’s done ground-breaking work in this area, recommended a biological age test as a way of taking a bearing on your longevity.

Check out his appearance on the excellent Rational Reminder podcast.

Just do it already

Plan F? I believe I covered that one at the start of this section.

You can’t escape the rat race by creating an adamantium-plated decumulation plan. You’ll never leave the grind.

I can conjure any number of phantoms if what I secretly want to do is to stay chained to my desk.

And whatever happens, I’ve still got my wits.

(“Oh dear. We’re fu-” – Mrs Accumulator)

The inflation problem revisited

The thing that almost keeps me up at night is inflation. It can be ruinous for unlucky retirees.

There are a couple of inflation beasties hiding under rocks that require consideration, beyond the threat of a reckless future government doing a ‘Weimar Germany’ or revisiting the stagflationary 1970s.

One is that your personal inflation rate doesn’t track CPI-inflation, nor even old granddaddy RPI.

There is in fact no chance that your personal inflation rate tracks the headline inflation rates exactly. So it’s worth getting a handle on it before you head into decumulation if your budget is relatively tight.

If our personal inflation rate goes wildly off-piste (which it has done in the past) then we’ll need to rein it in. Nominal asset returns and pension cost-of-living adjustments don’t give two hoots for our personal rate.

The second issue is hedonic inflation, which we’ve been warned about by Monevator reader ZXSpectrum48k.

Official measures of inflation don’t accurately measure rising living standards, as opposed to rising prices.

Nobody thought a mobile phone was a basic necessity 20 years ago. Or the Internet 30 years ago. Or anti-lock brakes on your car back in the Dark Ages.

ZX’s point is headline rates of inflation understate the prices we actually pay for items that are subject to hedonic adjustment, like a computer.

Technically the price of computing has plummeted in the last 25 years. Except that I pay more every time I upgrade, because my computer displays more colours than I can comprehend, and is so thin I could cut a house invader with it.

Maintaining your standard of living on this measure is under-researched (in fact I haven’t seen any research) and it could easily knock another percentage point off your SWR.

Which kinda drains the colour from my face.

No inflated expectations

I don’t want to end up like my gran who couldn’t afford a car until one of her sons was able to give her his.

On the other hand, my parents don’t understand the fuss about mobile phones. They have one each but they forget to charge it, or turn it on, so you think they must be dead.

They certainly haven’t found it necessary to figure out how mobiles work, despite having all the time in the world.

Then again, I can see why my retired parents, wafting around in full control of their personal agendas – and without any pressing need to be hyper-connected – don’t see smart phones as a fundamental human right.

Not every rise in living standards improves quality of life for everyone.

So while I’ll be gutted if I can’t afford the immortality drug available in Boots from 2045, I’m hopeful that we’ve got enough flexibility in our decumulation finances to afford those things we do need.

I see this problem as a chance to focus on what really matters. It’s just not worth spending another decade in the office trying to make ourselves bullet-proof.

We’ll live with less later if it means living more now.

Back-up plans aren’t foolproof

Do you trust your numbers? This is a psychological question more than a financial one. Decumulation looks like a high-wire act in comparison to the comparative cakewalk of accumulation.

Ultimately, you have to pick the numbers that let you sleep at night.

My decumulation plan is predicated on historical withdrawal rates crash-tested by two world wars, The Great Depression, and the turmoil of the 1970s. I find that pretty comforting.

Fair enough, I haven’t prepared the stables for the Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse.

My plan won’t cope with:

- The breakdown of society

- World War III

- Fascist coup / Communist revolution / The rise of the robots / A takeover by the Tufty Club.

I guess I’ll just have to take my chances.

Wish me luck!

Take it steady,

The Accumulator