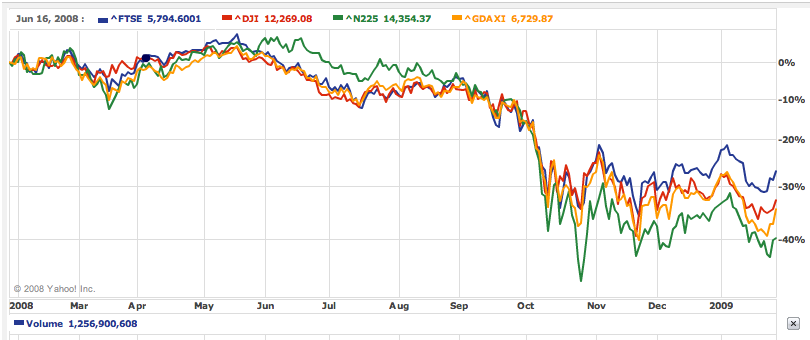

One of the mantras of those gloomy about Western economies is that we face a lost decade like that suffered by Japan.

In fact, Japan endured more than one lost decade, going on the performance of the Nikkei stock market.

Having hit a high of 38,957 in December 1989, the Japanese index had fallen to 6,994 by October 2008.

That’s a decline of 82% over 19 painful years!

But Japan’s lost decade wasn’t just about stocks. Economic growth came to a near-standstill in the 1990s. Worst of all, with house prices slumping, Japanese firms retrenching and personal consumption evaporating, Japan entered a deflationary spiral – despite near-0% interest rates.

With US and UK interest rates now hovering barely above zero and a convincing economic recovery still not apparent – especially in the US, which has a persistent unemployment problem – the doomsters see parallels with Japan in the late 1980s:

- The US tech boomed propelled the Nasdaq market to a peak of 5,049. Ten years after the crash, it’s at just 2,291.

- The FTSE 100 peaked at 6,930 in 1989. At 5,366, we’re still in a bear market.

- We had a lending boom and a banking crash, just like in Japan.

- The US is even flirting with deflation (unlike the UK where inflation is stubbornly above target).

These things keep investing refuseniks up at night, counting their gold coins, shotgun cartridges, and cans of baked beans.

We’re not turning Japanese

While there are echoes of our predicament in the Japan of 20 years ago, I personally sleep well and don’t expect a lost decade either here or in the US.

That’s because I see more differences then similarities with Japan.

In contrast, like stalkers looking for signs of love in a restraining order, the Lost Decade obsessives ignore evidence that contradicts their thesis.

The reality is that our cultures, economies, and our response to the financial crisis have been very different in the US and UK, compared to Japan.

Savers versus spenders

Perhaps the biggest reason for my optimism is I see very little chance of deflation taking root in the West.

The Japanese were once notoriously high savers. Just look at the following graph from Investor Insight:

Japan is a savings-driven culture, even today. Back in the 1980s, credit card debt was unheard of, and 20-somethings stayed at home for years to save a deposit for their super-expensive shoebox houses.

If you’ve got a lot of savings tucked away, deflation isn’t so bad. In fact, your money is worth more every year as goods and services become ever cheaper.

Japanese citizens could therefore spend their savings to top up their living standards throughout the lost decade. Terrified of debt – especially after that massive housing crash – even super low interest rates didn’t make the alternative attractive.

Compare that to the US:

US consumers only really save in economic downturns, as can be seen in the early 1990s, the recession that followed the tech bust, and the big spike upwards in savings in 2009.

While US households in aggregate have financial and housing assets to at least match their liabilities (contrary to the hype) they don’t have – and are not used to having – massive amounts of cash tucked away. Deflation would bite the US hard.

What this suggests to me is that near-0% interest rates – and quantitative easing – will work in the US, and here in the UK where the situation is very similar, because consumers would eventually start borrowing again.

If the authorities print as much money as is needed, we’ll get inflation and escape the deflationary component of Japan’s lost decade. That is half the battle won.

Response to the banking crash

The next difference to appreciate is between Japan’s response to its collapsing asset bubble of the late 1980s, and our own more recent one.

- The Japanese housing bubble was insane, and on a different scale to our own.

- Perhaps our tech boom was similar, but thankfully that never spilled out to inflate the value of all companies. (Instead they sold at bargain prices)

- In Japan, broken banks limped on for years.

- In the West, banks like Northern Rock and Lehman Brothers went bust.

- In Japan, banks continued lending cheap money they’d never get back until late into the 1990s.

- In the West, our banks have dialed back on bad lending and are actually hoarding cash.

- Japanese banks kept near-worthless securities on their books for years at inflated values.

- While our rules have been softened more than some critics would like, the US and European stress tests show we’ve flushed out the vast bulk of toxic assets, albeit at a huge cost to shareholders and taxpayers.

I’m not saying our banks covered themselves in glory before or after the crash, or that the transfer of risk from private companies to the State is without other consequences.

I’m saying these things have happened here, and a heck of a lot faster. So again, we’re different to Japan.

Different economic models, too

Finally, look at how we’ve responded to the recession in the West, compared to the zombie-like situation of Japanese corporates in the 1990s.

In the Lost Decade, much of what had been lauded in the Japanese economic model turned around to drag it under.

Not the good stuff – Kaizen, automation, and the just-in-time production lines that made Japanese factories the envy of the US rust belt.

Rather the networks of family and corporate cross-holdings, the jobs for life of salarymen, and the extreme desire to save face that also was part of the Japanese economic miracle.

It took a long time for the scale of the crisis to become apparent in Japan, because as I’ve said the banks obfuscated for years, as did politicians.

- Interest rates were far slower to fall than more recently in the West.

- Even when it was clear to everyone that Japan was in a hole, companies failed to shed workers or factories.

- Banks didn’t make savage writedowns over a couple of quarters like ours – they limped along, technically broken, for more than a decade.

- Cross-holdings between Japanese companies saw dying ones kept alive by healthy ones.

To be sure we’ve had some of this in the West. Lloyds and RBS survive due to taxpayer support, as does the likes of GM in the US.

But look at the bigger picture. The massive bounceback in corporate profitability and the coincident rise in unemployment in the West is evidence of capitalism working at its ruthless best.

Incidentally, demographics in the US are totally different to Japan, too. Thanks to immigration, the US still has a growing young workforce – yet another critical distinction that the Lost Decade doomsters overlook.

No easy ride, but no Lost Decade

I appreciate this may sound Panglossian to some readers, but it’s really not.

The Japanese experience is near-unique in our experience of capitalist economies. Even today it confounds the economic rules. It’s the exception, not our inevitable fate.

We might well suffer other bad stuff that I don’t expect, such as a double-dip recession or a period of extremely high inflation from our warding off of deflation. Our future standard of living has definitely fallen from where we expected it to be three years ago.

If you want gloomy scenarios, those are much more likely. But to say we’ll go Japanese is really a leap, considering how un-Japanese we were to begin with.

![The Japanese stock market crash: the bursting of a bubble [Members] The Japanese stock market crash: the bursting of a bubble [Members]](https://monevator.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Nikkei-225-Total-Return-1980-2024-1024x586.png)

Comments on this entry are closed.

Hi TI

Really interesting post. Some great food for thought in there.

As you know I’m an after inflation guy and those equity market price examples you gave look even worse adjusting for inflation.

The only thing I’m wondering is what do they do when interest rates get to 0%. Surely you can’t QE forever.

.-= RetirementInvestingToday on: It was all so predictable – Bank of England Rate held at 05 – August 2010 Update =-.

“If the authorities print as much money as is needed, we’ll get inflation and escape the deflationary component of Japan’s lost decade. That is half the battle won.”

No you won’t. Creating money doesn’t necessarily lead to inflation. You first have to max out the other two variables ‘velocity’ and ‘output’.

The trick is to create money and then deploy it effectively so that ‘output’ goes up. You don’t do that by giving it to a bunch of broken banks via ‘QE’, cos it’ll go straight to their balance sheet.

I’m not sure there is evidence of banks being balance sheet constrained. The issue is that there aren’t enough people chasing loans with a low enough risk profile to make what they are proposing viable.

What the government really needs to do is just net spend directly into the economy at the low end. Unfortunately it is doing exactly the opposite.

“But look at the bigger picture. The massive bounceback in corporate profitability and the coincident rise in unemployment in the West is evidence of capitalism working at its ruthless best.”

Yes, and it will until you realise that those newly unemployed were the people buying the products/services in the first place and now they can’t afford to. And more importantly because the credit cards/houses are maxed out they can’t *borrow* money to do so – which is what kept the boom going so long. Instead the newly unemployed start saving like mad/going bust.

So this half year might make good reading, but it is largely due to the deficit spending that happened over the last eighteen months. If that now stops then it will reverse unless the demand is replaced somewhere.

The real issue is this slump in demand, and that is what happened in Japan. Now it is happening globally so the usual panacea of an ‘export boom’ isn’t going to work. Since everybody is in the same boat who is going to do the net importing?

“The Japanese experience is near-unique in our experience of capitalist economies. Even today it confounds the economic rules. It’s the exception, not our inevitable fate.”

No. What it is hard data. And what that tells you is that the economic theory you’ve been working to is just plain wrong.

So you can get yourself a new economic theory that fits the Japanese facts, or you can wait for the confirmation that is about to happen. Either way the economic theory is bust.

@RIT – Well, QE goes beyond low interest rates. It literally involves boosting the money supply with a few keystrokes at the Bank of England, then as Neil says giving the newly created money to the banks in the hope that it will stimulate economy / drive down gilt yields / increasing lending / your own definition of QE success.

As such, there’s no finite end to – it doesn’t even have the practical issue that printing money did in the old days. Rather, the downside risks are potentially asset bubbles (some bears would say that’s what the stock market recovery is post QE) and hyper-inflation down the line.

@Neil – Thanks for spelling out the other side of the argument, albeit rather robustly. I have to head out for the weekend so I can’t write more now, but just to say I hope you’ll pop back here in a year / decade to compare notes. I won’t be going anywhere! 😉

(On the banks and lending, you may find it interesting to look at Barclays versus Lloyds’ results this week. The former has increased net lending to the UK, but its net interest margin has fallen, while the latter has decreased net lending by 1% yet seen net interest margin rise above 1% – and blamed consumers for paying back debt for the lower lending. So you pays your money and take your choice as to whether their constrained or not. Far from broken, I see banks riding the unusual new realities to suit them).

To Neil on printing money… well, so you say… Helicopter Ben was going to chuck it green stuff out over Idaho… I note that he’s in charge of the Fed and you (or for that matter me) are not.

To The Monevator, why are you so sure all the toxic assets are no longer on the balance sheets of the banks…? Even Sovereign Bonds are toxic these days some say… though I predicted QE from Trichet (on your other site stocktickle) and expect more to come.

Hi there,

Firstly, I want to push back on a point you made; you say that “The Japanese housing bubble was insane, and on a different scale to our own.” The housing bubble in Japan was insane but it wasn’t as insane as what we’ve seen in the UK and US, as this graph from The Economist indicates: http://bit.ly/cjXO19

I agree with you that there are some important differences between Japan and the UK/US that are encouraging: the speed of the policy response and banking clean being a big one; the flexibility of the workforce and relative integrity and stability of the political system being others.

However there are some important differences that are concerning. Firstly, in the US/UK it is the consumer sector that needs to clean up its balance sheet; in Japan it was the corporate sector, which accounts for a much smaller share of the economy.

The deleveraging of the consumer sector has some way to go here and therefore significantly risks sucking demand out of the economy and creating deflation. This has been called a balance sheet recession, and in such an environment, QE is useless, as it proved to be in Japan.

Another key difference is the state of the governments’ balance sheet. In Japan, the drop in corporate investment was offset by massive government spending. In the US and UK, the government has limited/no ability to step in and offset any drop in demand from the consumer sector.

So while the situations in Japan and the US/UK are not exactly the same, some of their differences actually increase the risk of creating a similarly protracted downturn.

Jim

Well, even though you were partly what convinced me that shotgun cartridges and tins of beans should perhaps not part of my future strategy 😉 there are other structural similarities with Japan. An ageing population applies to Europe at least, and some new hazards like an increased world population after what seem to be limiting supplies of energy and water.

Real incomes in the West have been falling for decades and credit is what has been masking that. My Dad working in a blue-collar job was able to support a family and buy his semi-detached house on a single wage. You can’t do that nowadays. Now that a lot of that fall in income is getting shaken out, and banks aren’t lending so profligately any more. The banks will do well, but the punters will get to eat the crow with disposable incomes squeezed even more by a) not being able to borrow and b) possibly having to pay down debts.

I am personally trying to save, reducing my spending like one of those cash-strapped borrowers. I will be a much smaller part of the British economy in the future than I was in the past as a direct result, at least as far as consumer spending is concerned, which is bad for British companies and jobs 🙁

I hope that you are right, though 😉

.-= ermine on: Greed is Good – are Animal Spirits returning to the Square Mile =-.

I think we’ll be in an economic slowdown for a number of years, but in the end we’ll be better off for it. Much of the growth in housing, company profits, spending, and lending was all done on shaky credit. We’re working to shake that out of the system and in the end, we should have jobs, spending, profits, and loans that are made on solid footing. It might be true that the days of huge growth across the board could be over, and this will disturb many, but in the end, if we’re on better financial footing, we’ll all be thankful for it. If anything, looking at the stock market, housing prices, etc. I think we may have already seen the lost decade but it just hit us that much faster.

.-= Money Beagle on: Flexible Spending Account Review =-.

I also don’t think we’re in for a lost decade. Like Money Beagle said, we may be economically slowed down for a little while and grow back slower than usual, but I doubt it will take 10-15 years and I think it will be very beneficial for us in the long run.

Hmm, based on the data that Japan’s citizens are huge savers, and they are stuck in a very slow declining economic spiral, I wonder why the US President, Mr. Obama wants the US citizens to save more?

It seems that saving more and job growth (people spending more) are on separate sides of the same coin…

Odd times for the US…

@MR – They *were* huge savers. If you look at the graph, the saving rate has more recently been declining. I’d expect deflation to end soon, too.

Great article Investor.

I worked for a couple of Japanese tech companies, during their heyday in the ’80s and ’90s. They were well-run companies, staffed with smart people. They copied American technology and produced their products cheaper than we could, with incremental improvements.

Both companies were very slow to react to market condidtions. One made dot-matrix printers and the other made copier sorters. Just like the Japanese bankers and politicians, they didn’t know how to handle the obvious changes. To be fair, I don’t think most people could have predicted what would happen to Japan’s economy. I sure didn’t.

@Bret – Glad you liked the article, and thanks for sharing your first-hand recollections. I especially agree with your last line – hindsight is always very wise, but it’s not so easy to predict things at the time! On that note, I don’t think it’s impossible the Lost Decade doomsters will be right and I’ll be wrong, of course. I think many of them could do with a tad more humility, however, especially given how badly they’ve tended to call the downturn and recovery so far.

@ermine and @moneybeagle – I agree there’s a ‘paradox of thrift’ effect happening in the West, particularly in the US where both corporates and consumers are now hoarding cash, which is ironically slowing down the recovery.

However even this relentless is very different to Japan in the 1990s, especially the early half where there was very little official recognition that there was a problem afoot.

People need to think about whether it’s most like they’re being influenced by their economic reading of our situation, versus how they read it 2/5/10 years ago, and how much they’re being influenced by stock market falls, bearish media and especially bearish bloggers. Generally, people are much more influenced by the latter, I’d submit. And that make stocks a buying opportunity in my book, because the gloomy consensus should be in the price. (Touch wood! 😉 )

@Jim – Very interesting graph, thanks. Of course there are lies and damned lies etc.

Picking 1995 for the starting point in the UK at least is potentially rather misleading, as that was at the very bottom of a huge former crash in the UK from the late 1980s. Houses were going for far below their long time price/earnings ratio. In comparison Japan in 1980 was, as far as I’m aware, already moving nicely along economically, without a similar slump in house prices in the late 1970s.

I’m not surprised therefore that our bubble looks worse in that sense. But I still believe Japan was a more extreme case… they had commonplace 100-year mortgages, properties getting mortgages at 10x earnings (as opposed to here where you had to lie to get that), Central Toyko land valued at the same as the state of California (or similar – I forget the exact specifics) etc.

Either way, you won’t hear me arguing we’ve not got/had a house price bubble in the UK/US. I’ve sat out the market since 2003 (much too early, as it happens).

I’m in a minority in that I don’t think consumer balance sheets are as bad as the consensus argues. Most evaluations ignore assets, which while well down after the stock crash (and real estate crash in the US) are still substantial. And our corporates are rolling in cash, with booming emerging markets to tap into if our markets remain sluggish.

Finally, on QE keep in mind the Japanese have not done as much or done it as swiftly as they might have. Even now, to make an extreme suggestion I don’t really see why the Bank of Japan doesn’t massage down the Yen by QE-ing by issuing Yen at the ridiculously low yields on offer and spending the result buying foreign assets, perhaps for a pension fund to provide for its aging population. Sure the Yen would wobble – that’s exactly what they want and need.

Thanks for your thoughtful comments.

@OldPro – I’m sure there’s still some dodgy stuff on the books, especially if ‘dodgy’ is taken to read, for instance, commercial property which is predicted to hold it’s value over the next 5 years or so, and you’re a perma-bear who thinks it’s all going to crash again.

What perma-bears need to be sure of is that they apply these ‘terrible things will happen’ metrics in the good times as well as the bad. If they do fair enough, but as far as I can see most of them are a swarm of self-reinforcing copycats seeing a disaster over one shoulder and therefore assuming there’ll be another around the next. Hindsight bias, in other words. (Er, and present company excepted!)

The Americans will not be able to save for long, they will need to spend it just as Japan did to buy the ridiculously higher priced food and gas. The stock market will drop hard just as it did in Japan because what follows inflation is deflation, and the only reason the banks are hoarding cash is because they are using it to prop up the markets, it isn’t even their money, it’s the people’s money from bailouts.

The banks in the West are gambling with our money, then when deflation follows through housing dropping further, and lasting years through lack of employment, everything will go like a pack of cards as banks hide their losses. Then they will start WW3.

It’s a pyramid scam, designed to get investors to part with their money so the banks can run for the exits at the top of the market, leaving the people owning crap of which many companies they hold stock in will go bankrupt.

@TI #4 & @Neil #2: an interesting debate.

Now 15 years on from QE starting, with multiple geopolitical & global public health crises inbetween, both of Neil’s observations hold water, namely that:

– “The trick is to create money and then deploy it effectively so that ‘output’ goes up”; and,

– “Creating money doesn’t necessarily lead to inflation. You first have to max out the other two variables ‘velocity’ and ‘output’”.

We had a very weak ‘recovery’ from the GFC, despite QE.

Austerianism rescued the bankers and the asset rich (the present writer included) but threw those less fortunate under the metaphorical bus.

That gave us Brexit and populism with their attendant traumas.

When inflation finally came it wasn’t as a result of QE (in 2009/10 or otherwise) but instead from a massive supply disruption following:

– a global pandemic that, all told, killed 17 mn to 24 mn in just 3 years.

– a well intentioned but (after Omicron) ineffective and ‘too high a price to pay’ 2021/22 second Chinese lockdown.

– An enormous war in Europe (with 450,000 Russian dead and wounded to date, and goodness knows how many Ukrainians, and now well into its third year, with a bloody grinding stalemate) which, via sanctions, cut off one of the world’s principal oil and gas suppliers from its European customers.

And, even then, and after all that, the inflation was a far cry from the 1970s, painful though it’s been for us all nonetheless.

Basically, in the aftermath of the GFC, we chose to forget our Keynes, and placed too much faith instead in the likes of Ludwig von Mises and F. A. Hayek.

@Delta Hedge — Um, I know I’m biased but I find it hard to take anything other than a victory lap on this article. 😉

True we didn’t get much inflation as a result of QE — but we did get inflation, and we certainly didn’t get deflation, which was widely predicted at the time.

I agree @Neil had a good grasp of the transfer mechanism, and like many (pretty much everyone, thinking back) I didn’t fully understand back then how QE would or more pertinently wouldn’t interact/interfere with the money supply.

Also growth hasn’t been gangbusters, even before the pandemic, although much better in the US than the UK.

But overall, 15 years on, no we weren’t Japan.

I score it 1-0 haha.

You were definitely right in the article, and fully deserve to take a win 🙂

QE rescued the US/EU from the Thirties redux, or from the fate of Nineties’ Japan.

It gave the desired low stable inflation, reduced unemployment, and in doing so avoided a deflationary recession in 2009 becoming a Depression 2.0.

@Neil’s comments in 2010 look now to better directed as a (IMHO effective and accurate) riposte to a somewhat different, but perhaps linked, argument that was going on from around 2009 to 2017: namely the austerity/spending debate.

The US managed this more successfully than the UK or Eurozone, notwithstanding the grand standing over the debt ceiling.

Over here we fell for Osborne’s seductive simplicities of TINA & ‘we’ve maxed out the nation’s credit card’. But there are always alternatives.

Public spending is not like a household budget; it doesn’t always crowd out private investment.

Moreover, neither public spending nor QE have led necessarily (at least directly) to any unwanted inflation. The inflation of 2022-23 followed the massive disruptions of Covid and Russia/Ukraine, not the BoE’s QE programme.

@Neil was right to suggest that what matters is whether or not the spending which money creation enables is used wisely to raise productivity (and I would add additionally to improve both the physical infrastructure and social capital of the nation).

Unfortunately, that didn’t happen in the UK. The BoE more or less got it right, but the political class failed abjectly. Fiscal policy was pro cyclic across the 2010s, whereas it needed to be aligned with the (appropriately) counter cyclic monetary policy of the era.

When it came, Brexit was a self inflicted wound, created as an all too avoidable consequence of policy choices. 15 years on from the GFC we may have avoided going Japanese, but we’re still a poorer and a shabbier country than we should have been:

https://www.itv.com/news/2023-12-04/low-growth-and-high-equality-leave-britain-in-relative-decline