Can you take the pressure when your portfolio is sinking faster than a sub with a leak? At what sorry depths does your brain implode and your stomach dissolve in an acid bath of its own stress?

That’s what risk tolerance hopes to tell you.

By staying on the right side of it, you’ll hopefully resist the urge to panic sell in a crisis as if you’re throwing small children in the way of an escaped lion that caught you pulling faces when you thought his cage was locked.

Knowing your risk tolerance helps guide your asset allocation so that you’re not over-committed to equities when the market drops.

But nobody’s born with an innate knowledge of their risk tolerance. You can take a test, but it doesn’t come with a reliability guarantee.

Also, ticking boxes on a questionnaire is an entirely different experience to coping with the emotional shock of confronting your first bear. 1

Bear market survivors

The surest test of your risk tolerance is how you reacted last time 20% or more was wiped off your wealth. (If that’s never happened to you then we have some helpful ideas in the next section).

Your first bear market raking represents hard won experience that you can put to good use:

- If you panicked and sold up then your asset allocation is too aggressive. You need to dial down your equities and dial up your bonds. Your risk tolerance is likely low or very low.

- If you felt worried but held your nerve without losing sleep then your risk tolerance is moderate and probably about right for that level of loss. You just need to consider a worse-case scenario (see the next section).

- If you rubbed your hands at the sight of securities on sale and rebalanced into the battered asset class then your risk tolerance is high. Consider a more aggressive position.

- Your risk tolerance is very high if, instead of praying for deliverance, you prayed for further falls so you could grab even better bargains.

Passive investing champion William Bernstein matches these reactions to the table below published in his brilliant book The Investor’s Manifesto.

| Risk tolerance | Equity allocation adjustment |

| Very high | +20% |

| High | +10% |

| Moderate | 0% |

| Low | -10% |

| Very low | -20% |

The non-equity part of the portfolio is in intermediate or short duration domestic government bonds.

- Your bond allocation equals your age.

- Your equity allocation is then adjusted higher or lower by your bear market reaction as described above.

- A low-risk 30-year-old would be 60% in equities and 40% in bonds.

- A high-risk 60-year-old would go for a 50:50 portfolio.

Whatever you do, do nothing in the heat of the moment. You may feel like you’re being water-boarded while Donald Trump screams “LOSER!” in your ear but hang on. Sales during a storm can only crystallise losses.

Aim to gradually increase your bond holdings a few percent per year in line with the table above.

If your behaviour under fire suggests you can handle more adventure, then you can think about upping your equity position.

But again, only gradually.

Remain alive to the possibility that you may not feel so calm in the future if a bigger loss rips a chunk out of your bigger portfolio.

Bear market virgins

It’s better to be opt for an asset allocation that’s too conservative rather than too aggressive.

That’s because one of the worst things that can happen in investing is that you panic-sell, lock in losses, and swear off equities for good – missing strong returns in the future.

If you don’t have a real-life reference point to work from then assume your first big losses will feel much worse than you can predict.

A cautious approach enables you to build up your capabilities rather than having your confidence destroyed by an early trauma.

We’re generally advised to assume that equities can lose 50% of their value at any time.

The UK market’s biggest real 2 return loss was -71% from 1973 to 1974.

And it lost over 33% in 2008.

If you missed that debacle, try this:

- Write down the equity value of your portfolio.

- Halve it.

- How would you feel if that’s the amount you had in six month’s time?

- How would you feel if it took 10 years before your equity portion recovered its original value? Would you hate yourself? Would you feel stupid? Sick?

- If so, repeat again only this time you lost 25%. Then 20% and 10%.

- Can you cope if your portfolio doesn’t recover for 10 years?

- Dampen your portfolio with bonds or cash until you reach a position you can live with.

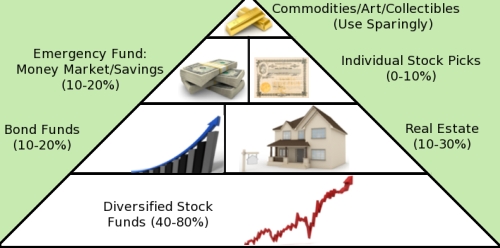

Prolific passive investing thinker Larry Swedroe has published the following handy table as another way to find that position by allocating more of your portfolio to government bonds.

| Max loss you’ll tolerate | Max equity allocation |

| 5% | 20% |

| 10% | 30% |

| 15% | 40% |

| 20% | 50% |

| 25% | 60% |

| 30% | 70% |

| 35% | 80% |

| 40% | 90% |

| 50% | 100% |

The non-equity part of the portfolio is in intermediate or short duration domestic government bonds.

All this said, as a professional party-pooper, it’s my sad duty to mention that there’s no guarantee that bonds will actually save you in a market crisis.

A 50:50 portfolio of UK equities and bonds still went down -58% in 1973 to 1974.

Like flood defences or an asteroid-proof umbrella there is no way to defend against the very worst that can happen.

But all the same, you are much less likely to suffer unbearable losses with a large slug in UK government bonds.

Risk tolerance fine-tuning

Don’t assume that your risk tolerance is a fixed characteristic.

- How you feel when you’ve got £300,000 on the line may be different to when it was only £3,000.

- How you feel when you’re 60 may be different to when you’re 30.

- How you feel when you’re close to your goal may be different to when you’re 20 years away.

- How you feel under strain may be different to when the market is buoyant and everyone feels invincible.

Err on the side of caution and be honest with yourself about how you felt during dark times versus how you would liked to have felt.

Don’t take unnecessary risk even if you can handle the consequences. Once your goals are in reach there’s no point letting Mr Market knock them out of your grasp again.

Pare back your equity allocation to take risk off the table.

If you need all your capital back within the next five years then you shouldn’t be in equities. Do the 50% loss exercise and see how that looks.

Self-education can improve your risk tolerance to some degree. Many Monevator readers report taking comfort from their knowledge that major losses are commonplace.

History also tells us that we’re likely to recover our losses within a few years.

You just need to view investing as a long game.

Try horror-binging on a gory book of past stock market manias and crashes to understand the polar extremes that we’re likely to weather in the future.

It’s a lot easier to deal with a crisis once you realise it’s normal.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

- A bear market is commonly considered to be a 20% fall from previous market highs.[↩]

- That is, inflation-adjusted[↩]

Comments on this entry are closed.

I think I have been very lucky with the funds that I have in my portfolio. Over all my portfolio growth in value and did not go bacmwards. While I was reading this article I was also re-evaluating my risk tolerance. Funds only takes 50% investment portfolio. And other 50% is on P2P lending and Crowd funding. I just took hit on a 2 defaulted loans and It really hurts. But thanks to growth on my funds, overall portfolio performance was acceptable. I think I would personally find 10% hard to swallow. 10% would be my personal limit. I don’t think I am mentally ready to swallow any number higher than 10%. I understand possibility of losses is part of investing but it doesn’t mean it is not going to hurt. I think it is imperative that time to time we have to re-evaluate our tolerance for risk and pain. Thanks for great article .

My risk tolerance feels very different regarding my SIPP and ISA. For my SIPP, I look forward to market drops where I can by more units for UT’s/ETF’s at bargain prices.

However, for my ISA’s I feel very nervous with any market drop, as I know I can take sell-up at any time (for a potential loss).

How do I “dial up my bonds” in an ISA context? All the funds I see seem to be equity-based. For example, the range of investment trusts from houses like F&C Asset Management — they’re all equities, plus a bit of real-estate.

Who’s got the collective-investment vehicles which are ISA-able and do the boring, steady, reliable UK-government fixed-interest thing?

My approach is to hold more cautious equities (mostly UK income growth investment trusts) that should ideally go down less than the market, and should hold or still increase their dividends, during any downturn.

I believe that investors should have enough employment income, cash, or dividend income so they do not have to sell anything to raise cash during a downturn that could last two years.

On a calendar year basis we have had seven down years in the last thirty years according to the FTSE All Share Total Return. Only 2001, 2002 and 2008 saw falls of more than 10%. Having been through those years and not sold out I believe I have a good tolerance for risk.

More recent investors could usefully study that history and consider their likely reactions.

@Jonathan.

See http://monevator.com/low-cost-index-trackers/

Read the information at the top, then scroll down to UK Government bonds. OCFs are around 0.07% to 0.15%.

I’m starting to realise what bothers me about coming up with one number for risk tolerance – I don’t need the money in my SIPP all at once. I’ll need a small part in maybe 10 years time, the rest I won’t need for 20 or 30 years, if I last that long.

This FT article by Don Ezra explains it better than I can – search result link (hopefully avoids the £) https://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwj5uq6zkbHLAhUGeSYKHUKqB6kQFggcMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ft.com%2Fcms%2Fs%2F0%2F3d32069e-da34-11e5-a72f-1e7744c66818.html&usg=AFQjCNGGN96Lm_XAlYCPiEHiMvv5XiQ62Q&sig2=ny80Rgz1SP4bV_LFyBrctw&bvm=bv.116274245,d.eWE

PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE stop calling a drop in the stock market a ‘loss’. It isn’t. It only becomes a loss if you have to sell.

No wonder the average person (and many finance ‘professionals’) don’t understand investing when a website as clever and useful as Monevator keeps on calling a fall in current market value, a ‘loss’.

No wonder the average investor panics and sells at the wrong time (ie after markets have fallen). You keep on telling them they have made a ‘loss’. They haven’t. And I know you (Monevator) understand that. But the average investor doesn’t.

You have a responsibility to use language more carefully.

Another risk related question to ask is whether you get more pleasure out of winning than misery from losing. People who do become gamblers, even if the odds are stacked against them. People who don’t might spurn equities as they think thats gambling too, without understanding the odds are in their favour.

So ask yourself, are you much more unhappy when the market falls than happy when it rises. If yes then you will be paying a financial penalty for your mental health. If no, be wary of the gambling that is frequent trading.

@John — I know what you’re saying but I see it differently. Your net worth is the sum total of your assets. If some of those assets are now worth less than before, you’ve lost net worth.

For those familiar with company accounting, it’s like a write down on balance sheet assets.

It’s only NOT a loss if it comes back in value. Of course we overwhelmingly expect markets to come back over the long-term (and in particular to shrug off short term wobbles) but if they don’t (1930s Germany, arguably 1980s Japan in practice, many individual shares of course) then it’s a loss.

What selling really does is it stops you benefiting from a recovery in prices, if/when they come.

As I say, I take your point and many novice investors would do well to think on it, but I think for me you overplay it for reasons above, and so I won’t be changing the language I use, personally. 🙂

Cheers for your thoughts.

It is good to have “rules of thumb” for managing risk, very useful. Thanks.

Currently I have savings, which are readily accessible, in a reserve which hopes to cover any unexpected expenditure needs in the near term (say 2-3 years). This helps me to not become a forced seller of either equities/funds or of investments held in tax free accounts.

Although various equity sectors or markets can perform differently, if there is a significant downturn then it can be felt over many markets together.

@John @TI

I fully agree with TI that a “paper loss” is a “loss” whatever adjective you stick in front of it.

To me it all comes down to what you do with the proceeds of the sale after you have “panicked” and how this affects your asset allocation.

If you leave the proceeds in cash you are really skewing away from your asset allocation against equities and so will not see the same return when/if equities recover. If you sell out completely you of course will never see it.

If you re-invest the proceeds in some mad high yield emerging market leveraged bond because the DT Money pages tell you “only an idiot would hold on to UK equities now”, you are skewing to more risk and either end up a star or broke.

I have sold UK Equities and Commodities several times in the last year or so as they have declined but have re-invested in the same asset class through similar but different ETF. I did this to crystallise a tax loss, that I judged was worth the transaction cost (trading plus spread).

So selling isn’t the problem, it’s what you do next…

(I find focussing on asset allocation and re-balancing provides a calm methodology for coping!)

Reading this post made us have yet another conversation about whether our equities portion (75%) is too high. This is starting to be a regular topic in our household, which is making us wonder whether we do need to re-adjust our asset allocation.

We are in our late 40’s and wanting to retire in about 2 years, so we are juggling two different objectives: 1) make sure that our investments are conservative enough that we don’t suffer (paper) losses before we need to draw on the our investments; 2) make sure that our investments are aggressive enough that we have enough to pay for a long (hopefully 40+ years) retirement.

On the positive side, at least we still have the option to postpone retirement a few years if the markets don’t cooperate. (Though, of course, we’d like to stick to our original plan of retiring around 50.)

@david m makes a good point: “Only 2001, 2002 and 2008 saw falls of more than 10%. Having been through those years and not sold out I believe I have a good tolerance for risk.”

We too survived those years without making any changes–with steeper drops in the US. But, of course, things are different when you are not only older but also closer to your goal–two items TA lists above about evaluating our risk tolerance.

Food for thought here, and an interesting (and timely) post. I’ve noticed my attitude shifting over the last decade, as my ‘there’s plenty of time to build it up again’ mind-set has waned. I’m almost 60, and I’ve worked for 40 years.

I’ve arrived at a comfortable accommodation for me – of my liquid assets, a third are in index-linked NS&I bonds, a third in index fund equities and a third in cash.

A large slug of my net worth is in a mortgage-free investment property, which provides a decent net return for only moderate hassle, as well as appreciating nicely over time even allowing for the CTG hit if I sold it. So far, so sorted.

But these unsettled times make one dwell on other types of risk, too. What really does my head in is my pension pot, currently in a DC scheme operated by my employer. It’s invested in index equities and bond funds, ‘lifestyled’ to age 65, which is fine for me and low-cost. At the moment, it’s covered by the advantageous deposit protection coverage provided for such schemes – fab, no need to worry at all.

But that will all change when I want to start to use the pension. Then, I’ll need to transfer it into a SIPP and that’s when the risk headache starts. Not so much allocation risk – I can cope with that. But structural risk, which is a whole other ball game. There’s no coming back from a loss of that type, and you have to rely on such investor protection as is available.

Multiple SIPP providers = less structural risk, but also = higher management costs (because most platforms give a reduction for size) and messy admin. The lure of putting it all into a tidy raft of V’rd LifeStrategy funds is tempting, but a range of fund providers = less structural risk but also probably = higher fund costs.

Dearie me. A nice problem to have, some might say, but a worry none the less and one that becomes more disturbing the older you get. I’d be really interested to know how others approach/manage structural risk.

Jane

A useful way of describing how and way risk tolerance changes over time is that it’s actually comprised of two components:

1. Your innate attitude to risk which is a psychological trait, is measured relative to a population and doesn’t tend to change much over time

2. You capacity for loss, which changes according to how close you are to retirement, sequence of losses and value of assets etc.

If you stick all these together with your financial goals, you get 3. – your need to take risk.

Matt

“A 50:50 portfolio of UK equities and bonds still went down -58% in 1973 to 1974.” TA

That’s a startling piece of data which raises many questions.

Having trouble picking out the figures from the link, but suppose we are talking here about real returns. In which case inflation and rising interest rates was the villain for bonds, coupled with a declining stock market?

Hiding in cash would not have helped! So dialling back on stocks would have been only a partial solution!

What would the best course for the poor investor have been?

Perhaps one lesson to be learned is that today we can hold Index Linked Gilts, and for the fortunate few, including it is noted some other posters here, long term holdings of the currently withdrawn NS&I IL Certs.

Any other ideas?

I remain baffled by the bond thing. The non-equity bit of my portfolio is in National Savings income bonds paying 1.25% gross. What incentive is there to put any of that money into gilts which give no more security, no or little more interest and a risk of loss of capital?

If you buy something and it’s current value falls, that’s a mark to market loss, which may or may not be relevant to you, depending on when you need the money, or part of it.

To me a paper loss, is making a loss from paper trading, fictitious trading, where you keep a note of what trades you would make without executing them. Might be OK for testing out a strategy but is completely missing the emotional stress.

In any case the only thing certain about markets is that they go up and down.

Magneto, I wonder if property investment trusts or gold might be a couple of ideas for asset classes that hold up in inflationary periods, although not sure whether they would beat index linked gilts (which were not around in the mid 70s) or how property investment trusts would have been affected by high interest rates in 1973/74.

I’m still puzzling how I can best fit a commercial property IT or ETF into my portfolio to offer less volatility than equities but a better yield than gilts or investment grade corporate bonds e.g. a better risk/return trade off.

I’m thinking my risk tolerance would allow for perhaps ending up with 50% equities, 30% bonds, 20% property ITs/ETFs in a drawdown portfolio where you live off the natural yield. But would need to run that mix through a 2008/2009 type scenario.

Ah fixed income, that misunderstood asset class.

The usual convention s that ‘bonds’ in an equity-counterweight context means domestic (£ denominated) government debt (default risk-free, or as close as you’d hope to get in the case of HM Treasury), ie gilts.

Totally agree that yields are low and that capital is at risk but typically when equity prices take a gut-punch, the fearful money sells and buys ‘safety’ in the form of gilts, driving prices up. While the par value of the bond stays the same, the mark to market value rises, delivering a capital gain to offset your equity losses.

Of course the converse is true, so while you and everyone else is riding the FTSE into the sunset, your gilts take an offsetting knock.

Increasing your bond:equity ratio tends* to both decrease your expected return AND your portfolio’s price volatility.

You can think of cash as a VERY secure bond with no duration. Counterbalancing equity with cash cuts expected return and volatility even more, but gives no capital upside.

Like any form of insurance, downside protection don’t come cheap.

You pays your money…

* cf Keynes and market irrationality.

Hi, i’m looking for a simple and easy way to invest passively, make monthly payments and forget about it for 10 years. If you had to put all your money and risk into one simple index, what would be the top picks?

I have now reviewed my approach (4 above) against the 1973-1974 market by looking at how some of my holdings performed then. The real (after inflation) total return drawdowns were around 51% – 57% and were not recovered until 1984-1985. Real (after inflation) dividend income fell by 10% – 18% and did not fully recover until 1984. The real income shortfall averaged 3% – 8% per annum from 1973 to 1983.

This would have been more testing than 2001-2002 and 2008. The problem was that the market drawdowns of 1973-1974 were accompanied by average annual inflation of 13.2% from 1973 to 1983. The real income shortfall would have meant that living standards would have fallen without a sufficient cash reserve to supplement dividends from 1973 to 1983.

@Grainne – If your avatar is a current selfie, stick it in a cheap global index tracker (see http://monevator.com/how-to-chooose-total-world-equity-trackers)

If your avatar is your daughter, or you read the above and thought ‘eek how scary’, stick it in a fund of funds like Vanguard LifeStrategy or similar, maybe looking for about 60% stocks.

If you’re 10 years from a fixed retirement date and planning on buying an annuity as you retire, more thought is needed and I don’t know enough.

If your monthly salary looks like my annual salary, you want an ETF (lower fixed one-time charges), for monthly contributions, if not then look for a fund (% charge, often with no monthly trading fee).

All the info you need to go passively DIY will be in the links from the Investing tab at the top of the page. If you need more help (or don’t believe strangers online), speak to an IFA.

Please guys

I am sitting on a cash hill (i.e. neither a cash mountain nor a cash molehill) in NSI income bonds, with a bit in lovely NSI indexed certs, and can genuinely find no guidance anywhere as to whether, and if so why, I should keep it as cash or stick it in gilts. I have a satisfactory proportion of stuff in equities and no immediate incentive to buy more equities with the cash.

Anyone?

“Magneto, I wonder if property investment trusts or gold might be a couple of ideas for asset classes that hold up in inflationary periods, although not sure whether they would beat index linked gilts (which were not around in the mid 70s) or how property investment trusts would have been affected by high interest rates in 1973/74.” SemiPassive

Casting mind back to those days, the early 70s, even though we were very far from financially astute at the time, the one thing we do remember is the rampant house price inflation. So direct holdings of Real Estate is one possible protection against such a repeat of real capital loss?

Gold scares this investor. With most investments should price fall one can seek solace in the continuing yield and maintain the holding through thick and thin. Unfortunately not so with gold. But others will praise Gold as a diversifier.

Over the years we have gently moved towards a ‘Well Balanced Porfolio’ of the four main income producing Asset Classes (Stocks/Bonds (IL and Nominal)/Cash/Real Estate). This has almost certainly been a sub-optimal allocation, but did has allow us to move progressively in and out of the asset classes as they fluctuated, taking advantage of the wilder swings to top slice and bottom-fill. Maybe such a ‘Well Balanced Portfolio’ is the best type of Asset Allocation an investor can hope for in the (unlikely?) re-run of the early 70s?

All Best

@R Lee — You say you there’s no guidance, but if you use the search box in the top right then you’ll find a dozen articles on bonds and cash on Monevator alone. And other websites are available. 🙂

I suspect what you want is certainty or for someone to tell you what to do. There’s never certainty in investing, but there’s no shame at all in needing professional guidance. Managing our own money is a great treat for those of us who want to do it and enjoy it, but it can be daunting and confusing. Strangers on the Internet can’t tell you *exactly* what to do — even if we were professionally qualified to do so, we only know the tiniest bit of your personal circumstances. Rather, a trip to a respected flat hourly fee charging financial advisor might be in order if you decide you’d like someone to help you make these decisions.

Anyway, as I say there’s no certainty in investing, only probabilities. As you’ll know if/when you’ve read all those articles about cash, bonds and gilts, the last do well in times of deflation. Such times are rare but they do happen. I still don’t expect it in the UK on a multi-year basis, but I’d say the odds for sustained deflation here are probably about as high as they’ve been in my lifetime, leaving aside ’08/’09.

So, I don’t expect it but it’s more possible than usual. Ultimately time will tell. As I say, no certainties!

The yield on the 10-year gilt is currently 1.46%. This is around about as low as it’s ever been, and 15 years ago it was around 6%. 20 years ago it was over 10%.

Today’s very low yield tells us (a) these are unusual times, likely distorted by QE and near-zero interest rates (b) I’m not alone in thinking there is a prospect of deflation (c) if there’s no deflation and the economy and money returns to something like what we consider ‘normal’, then the chances of further gains from gilts seem remote, and the possibility of losses higher.

So, no gilts then? Not so fast, remember I said the chances of deflation are relatively high.

Japan is a country that has been grappling with deflation for years. Its 10-year yield is as I speak negative. If UK 10-year gilts were to follow suit, they’d deliver strong capital returns. This would be the famous ‘buffering’ of bonds in action, compensating for the extremely large chance that equities would plummet in such a scenario. (Japanese equities have fallen sharply over past year, for instance).

So something good would happen (a capital gain) if something bad happens (deflation). Many people might think that is worth getting exposure to.

What about cash? If rates for retail investors fall to 0% but there’s deflation, cash is still useful — it preserves its value, because deflation of negative 1-2% means cash is getting more valuable every year. (The opposite of what we’re used to with inflation). However you do not get the potential for capital upside too, with cash, that you might with rising gilt prices in a deflationary environment.

Boil it all down and the reason nobody can tell anyone exactly what to do with certainty is because nobody knows what will happen. That is why investors — and especially passive investors — typically diversify widely across the 4-5 core asset classes.

Remember that the idea of diversification is not to get a bunch of assets that all go up. Something will definitely do worse if you’re properly diversified. The good thing about government bonds is their ‘worse’ is usually (not always) not as bad as the worst case for assets like shares or property, especially over the short term and in nominal terms. However there’s not much in the way of returns in normal times, either. The past 20 years have been very unusual in that respect (see last week’s article on UK asset class returns).

I’m not going to tell you what to do, I’m just stressing in the hope you find it useful that the information is out there, and that you won’t get the ‘right’ answer, except with hindsight.

Personally I’ve held no gilts for 5 years, and while I’ve done well with my investments anyway, I think that was a mistake in retrospect, in terms of risk-adjusted returns for sure. But I continue to be satisfied with cash as my buffer. However I’m a still young-ish and very active investor.

Most people are going to be better off picking their asset allocations, rebalancing as necessary, and concentrating on other stuff like their job or the football this summer.

And as I say, exploring professional independent — and ideally recommended by a knowledgeable friend — flat-fee charging hourly advice if required.

Hope this helps, though I am not sure what you wanted. 🙂

“Please guys

I am sitting on a cash hill (i.e. neither a cash mountain nor a cash molehill) in NSI income bonds, with a bit in lovely NSI indexed certs, and can genuinely find no guidance anywhere as to whether, and if so why, I should keep it as cash or stick it in gilts. I have a satisfactory proportion of stuff in equities and no immediate incentive to buy more equities with the cash.

Anyone?

Others, esp TI, will be able to provide far better guidance and links to past articles.

We too see Gilts as unattractive at present, but nevertheless hold INXG (IL Gilts ETF) as insurance against inflation, and to counteract the long duration of INXG, also hold IS15 Short IG Corps (NOT GILTS).

Occasionally we have been able to top-slice INXG profitably as stocks tanked, using the proceeds to add to stocks on their weakness. But this sometimes negative correlation cannnot always be relied upon.

But we also hold substantial cash! So if stocks and bonds both tank at the same time (as has occured in past), cash comes to the rescue.

Maybe it is all about “eggs and baskets”?

Bonds/Gilts are worthy of far more attention/discussion than we give them!

Will be watching responses with interest.

Golly, there’s a Rolls Royce of an answer, thank you!

I had seen some of the posts here and elsewhere prior to asking the question. Actually you have my situation back-to-front. I know exactly what I want to do, which is stay in cash, on the basis that if I move from cash at 1.25% to 10 year gilts at 1.46% I am getting that negligible gain at the risk of capital loss. I was wondering if I was missing something, but I now know I am not.

I see the point about bonds appreciating if you get deflation, but actually cash appreciates too with deflation if you measure its value in terms of the stuff you want to buy with it.

Thanks again. Love the blog.

R Lee, your personal situation and investment wrappers used will have a bearing. My take is I only hold gilts if they are within a SIPP/pension where a) the alternative of cash is zero interest bearing, b) you get 40% tax relief on the way in, and gilts dampen the volatility of your equities.

Outside of a pension I prefer cash in ISAs, or an offset mortgage account, or simply paying off your mortgage, or even premium bonds “it could be you!”

Investment wrappers is a whole other question, if you are earning enough interest to take you over the exempt limit and are also paying the new dividend tax.

Presumably bonds make more sense when interest rates are normal because they are inversely correlated with cash (lower interest rates = rise in value of bonds and vice versa)

Understanding the theories around the damping effect of bonds on a diversified portfolio, it’s still feels fundamentally counterintuitive to buy something now, when you know that a capital loss will follow eventual interest rate rises.

As someone who needs to bolster my non-equity proportion (held solely as cash up to now), but as SemiPassive suggests, bond funds/ETFs lend themselves better to SIPPs, I wonder if anyone has a view on iShares interest rate hedged ETFs, such as SLXH (admittedly, corporate bond rather than gilts, but it’s the principle I’m interested in). Do these get around the interest rate wrecking-ball, or have I missed a fatal flaw?

@NotKeith — You don’t *know* interest rates will eventually rise. It’s a very reasonable assumption, but it’s just a probability, not a certainty.

You also don’t know timeframes. Look at the following graph of yields on Japanese government bonds. Click the “Max” view to see the long-term collapse in yields since 1986!

Like you I think we’re closer to the end than the beginning of the bond bull market, but we (and many Monevator commentators, who I’ve argued (nicely! 🙂 ) similar with over the last few years) have been wrong so far.

We’ve even been called irresponsible or stupid for including government bonds in our suggested passive portfolios. Of course they’ve been a decent addition since that name calling. (They could have been bad, too. That wasn’t the point).

Finally, remember that in a mixed bond fund that is rolling over maturities, rising yields will dampen the effect of capital losses if/when we see those interest rate rises. The maths on this can be surprising to many people. Provided rates rise at an orderly rate, the capital losses may be a lot more moderate than you might think.

I’m not a flag waver for deflation and gilts — as I’ve said above I hold none currently — but words like “know” without a “probably” following do set me off… (Ask my co-blogger T.A. who has suffered from my tendencies here, too! 😉 )

Ack — sorry, I mean closer to the end than the beginning. Fixed now. 🙂

@TA …

That year in the early 70’s you quote is terrifying… As is the word ‘Japan’… But both scenarios involve holding equities from one place (ie UK or Japan)… A lot of monevator readers will be holding equities from the whole world over… How closely correlated are they do you think?

How much of the risk inherent with holding equities can be lowered for the same reward by holding alternative equities ?

The person holding their 50pc equity allocation in Vodafone is surely carrying more risk than their neighbour holding a basket of funds from around the world…

Apologies if either of you have written about this before.

@Planting Acorns — You might find this article interesting:

World stock markets: How historic returns have varied by country

I did 2 seconds research to see how a global equity exposure would have protected a UK investor in 2008. Bad news: the FTSE (down 31.3%) was almost the best performer of the year among world stock markets, beaten only by South Africa (-27%)

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/dec/31/shares-markets-record-losses

*cough* The iShares Gilt ETF (IGLT) rose 9% in 2008 and paid you (from memory) 4%+ income on top. *cough*

😉

@TI, thanks – had a look at the linked 2009 article as well.

@R Lee… Ah that is interesting, although I’m not convinced it was bad news ! The pound fell by 27pc against the dollar (and presumably therefore against a basket of currencies) so any companies denominated in foreign currencies would be worth more pounds…

@TI

I respectfully disagree.

If we were talking about vintage cars then I could possibly see your point. We’re not though, we’re talking about a productive asset – equity, which is simply the mechanism by which you gain a portion of future dividends. It’s this future income stream that forms the bulk of equity’s total return. And once I’ve bought 10% of XYZ Corp, I get 10% of profits for the rest of my life. It may be that when the share price falls OTHER investors will be able to buy the right to 10% of profits for less than I paid….but…well…good for them. From my point of view it makes no difference, I’m already enjoying my 10%.

I really think this is the very crux of equity investment. Mark-to-market is meaningless UNTIL you either buy or sell.

Keep up the good work though.

@John — Fair enough, everyone is entitled to see things how they see fit. 🙂 As I say, I won’t be changing my language though, and your view is contrary to the entire financial world. (For a non-shares example, try re-mortgaging your house, after it falls 50% in value in a house price crash, by arguing your equity stake should be based on the price you paid for it, not the current market valuation).

I don’t disagree with your wider point of course, as I’ve already said. 🙂 (In fact I alluded to a similar point with the chickens/eggs Weekend Reading post the other day).

Interesting and well rounded article – on risk tolerance – but risk is more than just about how you cope emotionally. There are three elements to everyone’s risk profile – emotional tolerance to risk; capacity for loss; and need to take risk, ie the rate of return you need to achieve to meet the cost of your goals. Whilst emotional tolerance to risk is always going to take precedence (it’s a hard wired behavioural trait, whereas you can increase your capacity for loss by adjusting your goals / lifestyle, and reduce your need to take risk by earning more, spending less, working longer, downsizing etc etc) you cannot look at it in isolation, you need to be thinking about all three aspects of your risk profile.

Thanks for this article, some really useful tips and tools here.

@CCG, yes it’s quite complicated. I found this article on combating your psychological biases quite interesting:

https://online.email.hsbc.co.uk/wealth/wealth-series/money-on-your-mind.php?WT.mc_id=HBEU_HSBC_Email_wealth3&WT.z_deliveryID=210060179&nid=170866849

@ Magneto – yes, -58% was real losses. Soaring inflation simultaneously did for bonds and equities. Inflation-linked bonds would be my solution as Semi mentions. Gold, not so much. Commodities should also do well when the inflation genie is on the loose, but I don’t invest in them due to the problems of finding an investment product that behaves like the underlying asset.

@ Jane – that is a nice problem to have and I’m jealous of your extensive NS&I Linkers – I was too late to that game. Splitting your pot between two or three different brokers doesn’t seem to big a price to pay for peace of mind. Here’s some more info on the topic: http://monevator.com/investor-compensation-scheme/

@ Grainne – It doesn’t get any simpler than this: http://monevator.com/vanguard-lifestrategy/

@ Planting – a good piece here on global (developed world bear markets)

http://awealthofcommonsense.com/2016/02/when-global-stocks-go-on-sale/

1973 – 74 wasn’t as bad as the UK (-40%) but 2007 – 09 was worse (-54%).

Diversification is no guarantee, it’s just the closest you can get. Dev world equities are highly correlated but spreading yourself across the world (including emerging markets) makes you less vulnerable to a multi-decade market flatline e.g. Japan. Diversifying into bonds makes you less vulnerable to the risk of equities as an asset class under-performing.

@ CCG – we take a tour through those other aspects of risk here: http://monevator.com/what-you-need-to-know-about-risk-tolerance/

@ John – my language reflects how people tend to feel in the moment rather than your cooler calculus of the bigger picture. Sure, when I look at losses my rational self murmurs ‘paper loss’ reassurances but I’m also home to a panicky chimp who runs around like his fur’s on fire. The reason I use more emotive language is to try prompt people to consider how they feel when the chips are down. It’s all too easy to be over-confident when everything is going swimmingly.

@TA … absolutely brutal !

Thanks for the link, re-emphasises your article and ‘mantra’ – of buying long, buying low cost, diversification, automating ( as you say the best discipline is the one you don’t have to impose 😉 ) … And rebalancing to lifestyle…

… I think I’ve got to grips to with what I need to do, bit like we all know we have have to run into a burning building if there are kids trapped inside… Guess the only test that matters is if you do it when the time comes !!

@Jane @TheAccumalator:

re structural risk / investorcompensation: I have multiple StakeHolder pensions with Aviva UK. When the total exceeded 50k I asked Aviva re the available potential compensation .

I got a written answer in 2015q2 : “For pension products the FSCS cover 90% of the claim with no upper limit (increases to 100% from 3 July 2015) for claims relating to long term insurance policies (such as pensions and life assurance). ” I was further assured my SH pensions came in this category.

I feel reasonably confident this applies to SH’s with other providers. Whether SIPPS are treated identically I know not (but I’d like to find out!).

@Tom:

Hi Tom – sadly, SIPPs are not long-term insurance products and, instead, fall within the ‘investments’ section of the investor protection regime. Bummer, I know…

Jane