An index-linked gilt ladder is oft touted as solving two big problems for investors:

- Hedge against unexpected inflation – something that by contrast inflation-linked bond funds have conspicuously failed to do recently.

- Ensure a predictable supply of real income to meet living expenses in retirement.

And it’s true! A ladder of individual linkers 1 can deliver on both these scores…

…but you have to watch your step.

Linker ladders solve some risks while introducing others.

So let’s run through the two main use cases, examining the pitfalls and potential remedies as we go.

‘Safe’ retirement income

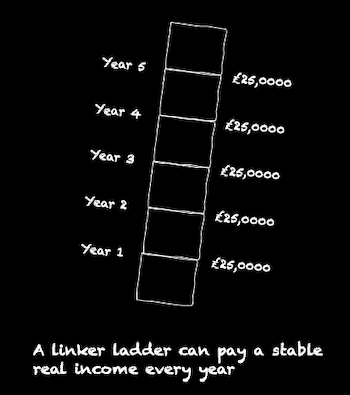

In principle, an index-linked gilt ladder is a much safer way of generating a retirement income compared to a volatile portfolio of equities and bonds.

Buying a series of linkers enables you to secure a reliable cashflow of government-backed, inflation-protected income.

Hey Presto! No more sequence of returns risk.

- See our member’s article on how to build an index-linked gilt ladder for further details.

A linker ladder has two big problems however:

- The danger you outlive your ladder. You build a ladder to deliver 40 years of income but then you have the temerity to last for 41. This is longevity risk incarnate.

- Relying 100% on ladder-generated income requires you to predict your after-tax living costs far into the future. Get it wrong – with insufficient alternative sources of income – and you land on the liquidity risk square. “Do not pass go, do not collect £200…”

Unexpected bills are as inevitable as their more infamous ‘death and taxes’ counterparts of gloom. Your financial firepower may have to deal with waves of such baddies in the future. Think divorce, chronic health expenses, family members in need of support, and social care – to name just a few end-of-level bosses.

Moreover, your personal inflation rate may outstrip official measures. Which means RPI 2 increases in purchasing power from linkers may not cover your needs.

Please sir, I need some more

Twenty years ago a laptop, a broadband Internet connection, and a mobile phone were not an essential part of life, never mind retirement.

Nowadays pensioners without these items find themselves sidelined by society.

Who knows what’s coming next? Personally, I’m factoring in a neural uplink plus bionic exoskeleton maintenance plan.

Meanwhile, higher taxes in the future could leave you with a lower net income than you anticipated. The country isn’t getting any younger, after all. The national fairy godmother isn’t waving her wand over the raggedy NHS. The military aren’t sure about that nice Mr Putin and there’s an energy transition to pay for.

True, you could sell an individual linker ahead of time to cover an emergency. But do so and then what happens when you arrive in the year 2049 and the gilt that was meant to fund that year is already spent?

It seems the twin threats of longevity risk and liquidity risk must be met by more than a ladder.

The floor and upside strategy

A floor and upside strategy can provide a middle ground between going all-in on a linker ladder, and depending entirely on the favours of the stock market gods.

Here your floor can be built from any blend of linkers, escalating annuities, the State Pension, and defined benefit pensions. Anything inflation-linked that provides ‘guaranteed’ income is ideal.

At the bare minimum, your income floor should cover your essential spending requirements. (That is, your non-discretionary expenses.)

Beyond that the upside is handled by a portfolio of investment assets. Fully 100% equities is often prescribed because the floor element effectively counts as your bond allocation.

The upside portfolio’s job is to grow and provide for the fun stuff. That is, it pays for the discretionary ‘nice-to-have’ part of your lifestyle.

You can dip into the upside portfolio to fund unexpected expenses, too. It can also extend your linker ladder if that nears exhaustion while you’re still going like the Duracell bunny.

Safety first

Your precise floor and upside formula depends on your personal circumstances. If your entire income (discretionary and non-discretionary) is amply funded by defined benefit pensions then you can afford to be more aggressive with your upside portfolio.

On the other hand you’ll need to be careful if operating on a super-lean essentials budget that’s barely covered by your ladder and an ‘It’ll be alright on the night’ personal philosophy.

Cutting it fine is not recommended.

Annuities are the right tool to combat longevity risk

Annuities come in for a bad rap. But index-linked (or escalating) annuities solve the longevity problem by providing inflation-adjusted income for so long as ye shall live.

If an escalating annuity funds the same income as your linker ladder – but for similar or lower cost – then it’s by far the better choice.

The older you are, the more likely it is that an insurer will offer an annuity product that makes it worth your while. (Though it’s interesting/alarming to note index-linked annuities are no longer available in the US.)

The key point is that an annuity income lasts as long as you do. In contrast, a linker ladder’s lifespan is finite (unless you can keep extending it using cash drawn from other resources).

You can quickly check the going rate on annuities with Money Helper’s excellent comparison tool.

Make sure you choose an annuity that’s linked to RPI and not one of the lesser ‘increasing income’ options.

At the time of writing I was quoted the equivalent of a 4.1% sustainable withdrawal rate (SWR) for a 65-year-old on an escalating annuity.

That compares well with a 3.9% withdrawal rate for a 30-year linker ladder. It also sidesteps the gymnastics needed to wring a similar SWR from a volatile equity-heavy portfolio.

No surrender

People tend to shun annuities because they don’t like handing over a big bag of swag to an insurance company.

Perhaps those people have not heard of a floor and upside strategy?

Moreover, they probably don’t realise that mortality credits make annuities the cheapest way to beat longevity risk.

Mortality credits are like the bonus balls in the lottery of life.

In annuity land, the spoils go to the long-lived.

Supercentenarians make annuity managers weep as they win their personal bet with the insurance firm.

One can almost imagine shady annuity goons trying to drop pianos on sweet old ladies in the street as the insurers desperately try to stem their losses.

But there’s no need, because they collect on those who fall at the early fences.

The house always wins. But so do you if you last long enough – and durability is precisely the risk you’re insuring against with an annuity.

Of course, linkers are backed by the UK government. But annuities are backed 100% by the FSCS protection scheme. During a crisis that may well amount to the same thing.

Juggling linkers, annuities, and the state pension

If you retire too early to make an annuity cost-effective then building a linker ladder to carry you to state pension age is a viable strategy.

The state pension will then help with the heavy-lifting from age 67, 68, 106 – or whatever your qualifying age is. (Unlucky, Generation Alpha!)

At that point, you can also decide whether to fund the rest of your income requirement from your upside portfolio, an annuity, a linker ladder, or a patchwork of them all.

Laddered couple

Monevator reader @ZXSpectrum48k has sketched out a helpful example of how this might work.

Picture a couple of early retirees, age 55. Their vital statistics are:

- Essential income: £21,000

- Discretionary: £7,000

- Portfolio: £700,000

A linker ladder funds £28,000 of income for 12 years until the State Pension arrives.

The linker ladder costs £320,000, leaving £380,000 for the upside portfolio.

The upside portfolio can then be left alone for 12 years, so long as the linker ladder is supporting expenses.

Alternatively, if a bombshell bill hits you could sell the portfolio down a bit to meet the payment. This will likely be fine provided you’re not systematically plundering it.

Then from age 67 the state pension (x2 in this case) takes over from the linker ladder to bankroll essential income.

Even if the Upside portfolio only stands still for the next 12 years, it could fund the remaining £7,000 of discretionary income at a mere 1.8% withdrawal rate. That’s pretty safe.

Let’s say the portfolio actually caved in by 50%, in real terms. It could finance discretionary income thereafter at a near 3.7% SWR.

That’s a reasonable SWR too, but especially so after a 50% decline. That’s because stock market valuations will have contracted. And the evidence generally shows that lower valuations support higher SWRs.

(Of course the 3.7% SWR is higher risk than the 1.8% SWR. And you’d leave a smaller pot behind for your heirs if withdrawing at a higher rate.)

Something for the weekend

Alternatively, from your late sixties onwards you could periodically check index-linked annuity rates. At some point your age and health are likely to make annuities a good deal for delivering the remainder of your income. Even more so if you don’t want the burden of managing a portfolio in your dotage.

Personally I’d still leave something in my ‘Upside pot’, regardless of whether or when I bought an annuity.

In later life this allocation could come to represent one last spin on the wheel of fortune.

Will it defray unwished for emergencies? Fund round-the-world trips, grandchildren, or a legacy? Or just fizzle away in an almighty stock market crash? (In which case, thank goodness you built your income floor first).

Much depends on the cards you’re dealt.

How long should an index-linked gilt ladder last?

Our example demonstrated that the length of an index-gilt ladder depends on what you’re using it for.

The doubt creeps in if you want it to last the rest of your life – so long as your date with destiny remains a tantalising mystery.

For context, according to the ONS’s UK life expectancy calculator, a female has a 6.8% chance of blowing out the candles on her 100th birthday cake.

Your income, health, and family history may indicate your chances are better.

I think longevity risk is easier to handle than liquidity risk. So I’d be inclined to overcook the length of my ladder.

Our post on life expectancy will help you think through the issues.

Take a butcher’s at our piece on life expectancy for couples too if you really like your other half. The odds are surprisingly high that at least one of you will last a very long time.

Meanwhile, if you’re using a linker ladder to meet a future expense (but without spending income en-route) then see our post on duration matching. Reinvest those coupons!

Upside portfolio management

Sustainable withdrawal rate research typically shows that 100% equity portfolios entail more boom or bust scenarios than more diversified allocations.

The unpredictability of equity returns can result in anything from you dying very rich to watching your portfolio drain inside a decade.

The lower your SWR, the more probable it is that a 100% equity bet pays off.

Conversely, SWRs much north of 3% from a global equity portfolio are edging into the danger zone.

Consider diversifying beyond global equities if your SWR is above 3% when you retire and the global CAPE valuation metric is well above its historical median.

A 90/10 split between equities and conventional bonds or an 80/10/10 division between equities, bonds, and commodities give you more options to fall back on when the stock market hits the skids.

In reality, your overall position should be more stable than implied by these equity-skewed allocations. That’s because your guaranteed income products and pensions all count as fixed income.

Using a rolling linker ladder to hedge unexpected inflation

You may not want to buy a linker ladder for the rest of your life, but maybe you’re still interested in protecting a wedge of your wealth from being withered by inflation.

Equities will probably do that over the long-term. But in the short-term, individual index-linked gilts held to maturity better fit the bill.

By holding each linker to maturity you avoid the price risk that has hammered inflation-linked bond funds over the past couple of years.

Bond managers typically sell their securities before maturity in order to maintain their fund’s duration.

As interest rates took off in 2022, managers were therefore booking capital losses as prices fell in response to rising bond yields.

Those capital losses were severe enough to swamp the inflation-adjusted component of linker returns.

Hold!

The bottom line is you can avoid price risk by acting as your own bond manager and holding your index-linked gilts to maturity.

To hedge unexpected inflation with index-linked gilts:

- Follow our How to build an index-linked gilt ladder guide.

- Construct a shorter rolling ladder instead of the long, non-rolling ladder discussed in the guide.

- Hold 0-3 or 0-5 years worth of index-linked gilts – just as a short-term bond fund would.

- When a linker matures, reinvest the proceeds into a new linker at the long end of your ladder.

Now you have an investment that directly responds to UK inflation.

You can reinvest your coupons into the ladder whenever you have enough piled up to make it worth your while. Or you can spend them, or reinvest them into another asset.

However you must reinvest the coupons if you want to achieve – approximately – the yield-to-maturity on offer when you first buy each bond. (This involves duration matching and is difficult to do perfectly.)

Remember, your linkers’ pricing will still bounce around as market conditions change. So you’ll still feel the volatility if you track your gilt’s fortunes from month to month. Moreover, you’ll crystallise any loss (or gain) if you sell early.

However, all told the volatility should be relatively tame on short-term linkers. And, as mentioned, you can ignore it entirely if you hold your gilts to maturity.

We’ll write a post soon on how to buy individual index-linked gilts.

But in truth – providing your platform offers them – it’s not much harder than buying a fund or share.

Granted you may have to buy over the phone instead of online, but it’s completely doable.

Stepping up

After many years of negative yields, individual index-linked gilts are affordable and worth buying again.

The window may not stay open forever. We might well fall back into negative real yield territory.

But for now, in an uncertain world, linkers offer something few other investments do. Just so long as you know how to make the most of them.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

![How to build an index-linked gilt ladder [Members] How to build an index-linked gilt ladder [Members]](https://monevator.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/index-linked-gilt-ladder-1-1024x212.png)

Great article, and opportune.

FWIW, I recently made a tool to build gilt ladders, https://lategenxer.streamlit.app/Gilt_Ladder , supporting both indexed and non-indexed gilts. I made this because I too am considering using gilts to fund certain short / medium term liabilities.

> Of course, linkers are backed by the UK government. But annuities are backed 100% by the FSCS protection scheme.

That’s good to know. One of the complaints I recently heard on annuities was precisely that the counterparty risk, but it was a north american speaker.

Annuities probably deserve their own post. One thing one might want to do for example is to buy the annuity later in retirement.

> We’ll write a post soon on how to buy individual index-linked gilts.

Indeed such a guide would be useful. I bought my first bond a few weeks back on IWeb. It went ok because I was aware of the pitfalls (clean vs dirty prices, prices quoted in nominal £100 units but units purchased in nominal £1), but it could easily gone awry ending up buying more/less than desired.

still think 2 to 4 years in cash and equites tracker is the way to go. cash as you mention is your bond and if you can find interest rates for cash then like we have now then all the better but of course that is the future

@ MCM agree Cash is good for many reasons but the linkers are almost tax free (most are low coupons) as are low coupon gilts. To me that is very valuable as the ISA rates are ok but I would rather have equity in the ISA for capital gains savings than a fixed rate on cash. Seems to me that annuities are good for a fixed base income and best come from the drawdown part of the pension as you have to pay tax on the income, but at 3.6 % for RPI linked (at 60) it feels like taking money from the pension pot is a just as reasonable as long as you don’t stress!

@TA:

As I am sure you recall, IMO floor and upside has always been the way to go.

I am some seven years into executing such a strategy, and the key lesson from my experience to date is that plans change – often in response to events entirely outside your control and/or influence. Hence, reversibility can be a useful feature. Annuities are rarely this flexible though.

At the next level down, by design, I chose to not to cut things too fine with my flooring. I also locked-in at the outset some 85% of the flooring I estimated would be required until I took my DB pension. However, I never once spent my annual budget and just rolled forward any unspent flooring. Then, I commenced my DB pension several years earlier than I had initially planned. There are probably numerous mistakes/lessons in all of this, but I guess it could have gone the other way too.

The late, great Dirk Cotton used to say the trickiest decision in an F&U approach is just how much of your Pot to dedicate to flooring; as in so many things he was not wrong!

I note an email today from Freetrade highlighting the imminent opportunity to buy “UK Treasury Bills”. Bit of a foray into the small retail world for zero coupon instruments? Marketing over usefulness?

Great post and very timely as I am neck deep in spreadsheets working out what approach to take to give me a “guaranteed” income without buying an annuity. Over the past few months, I have been building up a gilt ladder to provide a base level of spending between retirement in a year or two and the state pension. The question I have is, can nominal gilts also be useful for building the ladder? The way I see it, future inflation expectations are taken into account for the nominal. An IL gilt will work out better for unexpected inflation. A nominal if inflation is less than expected. So I was thinking of going for a 50%/50% split. Or am I looking at this incorrectly?

I notice mention of “longevity annuities “ in the USA where you retire at say 65 and purchase a deferred annuity that pays out between 75 and 85. If the latter, you could finance the first 20 years of retirement with a bond ladder and the deferred annuity comes into play if you make 85. I have not seen these explicitly for sale in the UK, the deferred annuities on offer here tend to defer payment for a much shorter period.

https://www.cnbc.com/amp/2021/10/22/longevity-annuities-can-be-a-good-deal-for-seniors-but-not-many-people-buy-them.html

@Mr H (#6),

All of my purchased flooring was in nominals – no automatic inflation uplifts. I just assumed a flat level of inflation across the period and included that in the yearly ‘budget’. I chose 3.5%PA; it worked out just about OK over the period in question, and I was well ahead for the first few years. But we all know what happened then. I also assumed no interest/coupons and that more than made up the shortfall to inflation – as measured by CPIH. IMO, RPI is a fundamentally flawed measure which generally over-states inflation. Also, I can see the attraction of the so-called personal inflation rate, but happen to see it as practically unactionable; and I have tried!

If I were to do it again I would set my level of flooring lower. I think the “correct” level is to floor your ‘essentials’ if you can actually work out what that is in advance. It turns out that I couldn’t and – at the time of pulling the plug – I had some twenty years of fairly accurate records too.

Having said that, sh*t happens and that was what I was trying to allow for.

I essentially floored what I thought was our lifestyle in a very conservative manner. I also over-estimated our lifestyle too. So all my ‘errors’ compounded in the same direction; but I guess they could have gone the other way too.

Furthermore, I would advise that if you are looking at floor and upside you also have a ring-fenced instant access reserves fund of TBD years of foreseen expenditure too. I did and I have not spent any of that either to date; but I still think the idea of dedicated Reserves is sound!

Key questions IMO are:

a) if you floor to your lifestyle what is the upside actually for, especially if you also hold reserves too?; and

b) can you really know what your retired lifestyle will cost in advance

As I hinted in (#4) above, my assumptions turned out to be rather conservative, but so be it. And sleeping soundly is nice too!

Retaining a fair degree of flexibility IMO is essential. Things will inevitably evolve in ways you did not and could not foresee. To paraphrase Macmillan:

‘Events, dear boy, events’.

Re: 50/50 split: you pays your money, and just be happy you can live with your decision ….

@HS (#7):

AFAICT these are not generally available in the UK. Having said that at least you can still buy inflation linked annuities here!

Thanks for another great article @TA. Plenty of food for thought on using F&U to bridge gap from legacy DB FS scheme retirement age (60) to current DB CARES & State Pension retirement age (68 when I reach it). Beats the ‘alternative’ of part retirement @60, which likely just means being given same workload for less pay 😉

These are great articles highlighting how I think you need to switch your thinking in the transition from Accumulation to Deaccumulation. I’d recommend the four pillars by Bernstein even if you have a previous edition as I do as it is extensively re-written. It helped me frame all these considerations for my circumstances.

I did/am doing the linker ladder out to 30 yrs at current family expenditure. So not really F&U. Included in my considerations were solutions for: if I died tomorrow (I don’t have a TI in my corner unfortunately), tilt towards guranteed income in early yrs as don’t want to live on floor income if equities hit a 20 yr flat patch, purpose of Up side (how much income/inheritence is help or hinderence), retirement spending smile (trending down by 1% under inflation p.a.), cognitive decline, & any possible future inheritences boost risk assets, but aren’t critical.

Finally, I tried to minimise taxes (annuites & SP) and maximise the 25% PCLS) whilst considering which drawdown method to use. It’s quite the cauldron of options and levers to think about!

@Sleepingdogs (#11):

Have you considered anything other than indexed linkers? I ask as if my experience to date is anything to go by (and for info it is definitely not unique) – see above – it may take you a few years of being retired to better understand what your retired lifestyle might initially cost. For completeness, this could range from less than current lifestyle to more than current lifestyle. And, of course, things can (and almost certainly will) change too. Think about the go-go, slow-go, and no-go model of retirement phases. Your current/historical spending data can be a handy guide but it is unlikely in my experience to be an accurate guide for the first stages of deaccumulation.

A pseudo-ladder of FSCS guaranteed fixed rate savings bonds* (or CD’s as our US cousins like to call them) coupled with an assumed rate of inflation could be worth a look. Mixing and matching flooring products may also offer some additional flexibility [and/or risks] too. Please remember that linkers are only guaranteed if you hold them to maturity; i.e. sell them early and you could face a loss. IMO predicting the next thirty years with any certainty is nigh on impossible. If nothing else, the last seven years have fully reinforced the extent of such a challenge.

I also note you make no mention of explicit Reserves. FWIW, I am convinced that this is just as sound an idea in deaccumulation as it is in accumulation.

Lastly, if you like the F&U approach IMO the best [technical] text is “retirement Portfolios” by Michael Zwecher. It is written for the US market (but reading across to the UK is not too hard); having said that it is not the easiest of reads, but is fairly comprehensive. I bought my copy of Z years ago (a few years before I pulled the plug), and it remains my go-to text. I do however consult it far less often now. What, unfortunately, is lacking in Z is any real world execution experiences/lessons, etc. Sadly, this is also almost totally absent from the net too; although Dirk Cottons Retirement Cafe blog is still active.

*Unfortunately, UK CD’s are now less flexible than they used to be and often cannot be surrendered early or, if they can be surrendered early, require a forfeiture of some interest or payment of some other penalty. The longest UK CD term I recall seeing is seven years, but more usually they max out at five years.

@ Mr H – I think nominal bonds vs linkers when constructing an income floor is a good example of Pascal’s Wager. The potential upside from nominals is marginal if inflation proves benign. But the downside is potentially ruinous if inflation runs amok. That said, much depends on circumstances… I’m imagining a ladder lasting for 30-40 years without much in the way of reserves if it goes wrong. You may only need the ladder to last for a decade and have plenty of reserves to dip into.

@ LateGenXer – awesome work! Thank you for sharing.

@ Al Cam – re: judging future expenses, I was struck by @BBBobbins suggestion (https://monevator.com/index-linked-gilt-ladder/#comment-1731638) of splitting spend into 3 pots rather than the traditional 2.

BBBobbins 3 pots are:

Essential

Lifestyle

Discretionary

This makes more sense to me than the traditional hardline drawn between discretionary and non-discretionary.

I’m interpreting what BBB had in mind but I think of essential spend as the non-negotiables: food, heating, fuel etc. I’d want that element covered by linkers or an index-linked annuity

Discretionary is ‘nice-to-have’ and life would still be good – if less exciting – without that spend. I’ll cover that with the portfolio.

Lifestyle is the grey area. I could live without items in this category but it would be a spartan existence. I’d cover this area with guaranteed income if I possibly could, or as much as possible. If not, then it’s over to the portfolio. It’d be worth going back to work to earn the readies to pay for this stuff.

What I really like about splitting expenses into 3 like this is that I’m forced to think harder about what discretionary means. In extremis, discretionary is anything which isn’t putting food on the table and a roof over our head. In reality, that category contains items we’d happily live without, and items that are important to our quality of life.

“Fully 100% equities is often prescribed because the floor element effectively counts as your bond allocation. ”

If the floor element consists of DB pension, state pension, or RPI annuity then since these could be considered as perpetual bonds (at least for a lifetime) then this is probably fair enough – although see my second point). If the floor consists of an inflation linked bond ladder, then as this is spent down the amount in the ladder (and hence ‘bond’ allocation) decreases with time and changing equity allocation in the residual portfolio might be considered.

The second point is that risk aversion (not everyone was happy to hold 100% equities even in accumulation) and the potential for a change in circumstances can also militate against holding 100% equities even if expenditure is fully covered by RPI sources. For example, assume essential expenditure and most/all lifestyle expenditure for a couple is covered by DB and/or state pension. In the event of the couple dying, the state pension element will be halved as, potentially, will the DB pension (depending on who held the DB pension). This may result in the flooring falling below essential expenditure levels and income from the portfolio being required once again. Having a portfolio with an asset allocation already below 100% at that point may be useful.

“After many years of negative yields, individual index-linked gilts are affordable and worth buying again.”

Even with negative yields, a ladder may be able to support greater income than a simple stock/bond portfolio. For example, modelling of UK and US retirements in https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4256534 (not peer reviewed), suggests that for the UK even real yields as low as -2% would have improved portfolio survivability – but shorter ladders were necessary. While that paper doesn’t cover it as well as it could, later work has suggested that the optimum ladder length and spend was one that gave an income slightly below that required with the remaining spend made up by the residual portfolio. I also note that the paper fixes the asset allocation at 80/20 while the ladder exists rather than, more correctly, gradually reducing it with time (again something covered in later work).

@TA:

Pascals wager is IMO just one aspect of it. The over-riding lesson from my experience to date is that you do not want to lock yourself in [to anything] anymore than you absolutely have to, especially from the very outset of deaccumulation. Things will change! And this will probably never stop changing either. How to assure flexibility (inc. at least some reversibility ie the ability to change your mind) is a personal choice, but most options have downsides as well as upsides. IMO, there is no perfect retirement product that is well suited to likely real world experiences.

The split of expenses into two types is tough enough; IMO three types just makes it even more complicated. I think there is actually a better way to parse your expenses, specifically recurring vs one-offs. These then may be further sub-divided into essentials and non-essentials if you are so inclined. A new roof is hopefully a one-off expense, that beyond a certain level of patch-up jobs it may well become essential. IMO the split is actually only of academic interest, the key point is that flooring your whole lifestyle (prior to retirement) could prove to be be wasteful or, on the other hand, too little! With the benefit of hindsight, trying retirement for a bit, and finessing things as you go along is probably a better approach. FWIW, it took me years (and I do mean years) to accept that I had purchased too much flooring in advance even though I spotted the signs very early on!

I would definitely look to hold Reserves. If nothing else, the logical approach if you under-spend is to put any surplus into your Reserves, and if the Reserves grow beyond a certain limit, upside the excess. I did not actually do this “upsiding” which came at a not insignificant opportunity cost to me.

The role of the upside is somewhat situational, some folks may see it as a legacy pot, others as dry powder to cover unknown unknowns, etc. In most cases IMO it should not be seen as a rose garden that you admire as it grows unbounded until you pop your clogs. However, this is a very real possibility if you floor your whole pre-retirement lifestyle from the outset.

“People tend to shun annuities because they don’t like handing over a big bag of swag to an insurance company.”

The annuity puzzle (i.e., why don’t retirees buy annuities when it is in their interest to do so?) has been wondered about since at least 1985, with, as far as I am aware, no-one yet coming to a definite answer (although your point quoted above features heavily). It probably also explains why nominal annuities are more popular than ones with any of the various types of escalations (80% or more are level if memory serves, data from a while back can be found at https://www.fca.org.uk/data/retirement-income-market-data-2021-22 – it will be interesting to see whether the recent bout of inflation has changed these stats) since people underestimate both the potential effect of inflation and their longevity (particular since there is ~10% chance of one member of a 65 year old couple surviving to 100).

I also note that the payout rate on a joint RPI annuity with 100% survivor benefits is closer to what can be achieved with a ladder and if there is a legacy motive, then this can tip the balance

One reason for this is that with level annuities insurance companies have a lot more things to invest in with higher returns than gilts (e.g., corporate bonds) while for RPI annuities they essentially only have index linked gilts to invest in. So, while there are mortality credits, these are weighed against fees and little or no outperformance compared to the retail investor. McQuarrie’s paper on the ‘annuity wager’ is interesting in this respect (although he only deals with nominal annuities).

@TA:

IMO a rather useful diagrammatic overview (from Pfau) can be found by putting “Pfau RIO Map” into google images. RIO = Retirement Income Optimisation.

@ AL Cam. Yes I’ve got cash, equities, nominal bonds 15 yrs duration (proxy for eventual annuity purchase), and a small DB pension in the mix plus two staggered SP’s. The equity is lower than I’d like at circa 15%, but this will be topped up with any extra income/wind falls that may come our way.

I’m somewhere between comfort and luxury retirement income on those surveys that make the rounds occasionally. Yes, I’m probably over egging the guaranteed inflation proof assets, but it helps me sleep at night. I now know that I don’t have the gung ho I had with a salary coming in and the inflation bogey man is the one that really scares me. I’m looking to avoid dieing poor rather than getting richer. Thanks for the book tip, I’ll look into that one…

Sensational news (to me anyway): from Inv Chronicle:

“That said, there are funds that function more like direct bond investments. iShares launched its iBonds ETFs, the first fixed-maturity bond ETFs in Europe, earlier this year. They mature on a fixed date just like their underlying portfolio of bonds, at which point they pay out their net asset value (NAV) to shareholders. That allows investors to build so-called ‘bond ladders’, a strategy that involves buying bonds with equally spaced maturity dates in order to reduce interest rate risk, by buying ETFs rather than individual bonds directly.

https://www.investorschronicle.co.uk/ideas/2023/12/14/should-investors-keep-on-buying-bonds/

To me this is truly sensational news, partly because Lloyds where I have my trading account say “ring us” if you want to buy bonds, presumably at £40 a pop. I am much more comfortable buying ETFs.

@B. Lackdown, I have 3 problems with available iShares iBonds:

1. they’re US Treasury’s, not UK’s Government (US is giving higher interest now, but that could change)

2. they’re in USD, not GBP (so currency risk)

3. being inside a fund, they’d not be exempt from CGT (all return would be taxed as income)

But I’ll admit that buying gilts directly has its challenges, and I’d be tempted to use iBonds inside a tax efficient wrapper like ISA/SIPP if iShares provided UK equivalent ETFs.

@lgx thanks, useful points. Not sure why my post has disappeared…

Now it’s back

More good news, email from those nice chaps at AJ Bell saying price of a trade for shares etf etc dropping from 9.95 to 5.00 from April 1.

@B. Lackdown — I’m not sure what happened either. I saw your post in moderation and approved it, but it shouldn’t have appeared before. Possibly either myself (or @TA accidentally) marked it as spam somehow.

No problem, and merry Christmas to you and TA.

@LateGenXer, @B. Lackdown: perhaps these iBonds are a 1st product creation response (i.e. cashing in) to pretty much the whole of the duration range for US TIPS briefly hitting 2.5% p.a. real yields and conventional US Treasury Bills hitting 5% p a. nominal yields.

For a short moment before yields fell back you could, in principle, have put 50% of the $ equivalent value of a portfolio into 30 year TIPS and have been guaranteed a $ return adjusted for (US) inflation after 30 years of 100% of the $ starting value of the portfolio.

Assuming the starting value purchasing power of the portfolio in year one was sufficient for your needs in year thirty (an extremely big assumption to make, obviously, and one which would have been unlikely to have been applicable for many people) then you’d have been essentially free for 30 years to take as much risk as you’d like with the remaining 50% $ portfolio start value.

Even if that remaining 50% went all the way down to zero, you’d still have gotten the full $ value starting purchasing power of 100% of the portfolio back at the end of the 30 years.

Of course, there would be FX risk on USD to £Stg over three decades. That uncertainty could have worked both ways though, either to one’s detriment or benefit.

Sadly, those real TIPS yields of 2.5% p.a. lasted all of a matter of days, and we’re now back well below 2% p.a., albeit still a much higher figure than the current equivalent real YTM on ILGs.

@TA:

This recent post from the Kitces blog proposes yet another way to parse/categorise expenses:

https://www.kitces.com/blog/retirement-spending-increase-financial-advisor-client-guardrails-guaranteed-income/

and uses a histogram-like sketch to illustrate what they are getting at. OOI, this is very similar to the approach recommended years ago by Jim Otar.

@Al Cam (27) I think the Kitces blog article of distinguishing expenses between Core and Adaptive is slightly more useful than the usual Essential and Discretionary. Personally I would deem it highly desirable for Core to be covered by guaranteed income. Fortunately for me, my more than six years of retirement have demonstrated that I have achieved this, as I seem to live quite comfortably within my DB and state pensions (plus a very small level annuity purchased because of a vagary of a small Section 32 DC pot).

I’m sure I’d be characterised as a ‘Tightwad’ in the description used in the article, but I don’t consciously hold back from spending on Adaptive if I identify something I want or need. Nevertheless I seem to be able to cover this from guaranteed income or earmarked savings (e.g. car purchase), so do fret that I should somehow expand my lifestyle to actually start drawing down my portfolio.

It was interesting to read in the article that reluctant spenders are more inclined to spend from guaranteed income than draw down from a portfolio (once they had overcome the initial pain of the annuity purchase!). Indeed, although I clearly have no need of further guaranteed income, I have often considered whether buying more guaranteed income would somehow induce me to spend more (I have no legacy motive). This feeling has intensified as annuity rates have improved and as I have aged. One factor constraining me is the prospect of fiscal drag leading me into the higher rate tax band if I fix additional income rather than accessing it flexibly.

As this article is about index-linked gilt ladders, I should have discussed in my comment above that a ladder with low-coupon gilts would be one method of increasing my guaranteed income for a fixed time period while minimally increasing tax liability. As, in my case, Core is already adequately covered, it would not be a serious problem if I outlived the ladder. It would best be done with unsheltered assets, of course.

@DavidV:

I recognise most of the points you make.

The principal reason I took my DB several years earlier than initially planned was that it became clear that I did not need to maximise everything and that an actuarially reduced pension would probably be ‘enough’.

As I mentioned above, if you floor your entire lifestyle [with guaranteed income] it is a very real possibility that any upside could grow unbounded until you ‘pop your clogs’. Clearly this is not the worst problem to have, but it is possibly wasteful?

@DavidV:

P.S. the Blanchett & Finke paper referenced from the Kitces blog post is worth a read.

And @Alan S (#14) nicely outlines the survivor scenario that may apply. In essence, the living costs for survivors are usually greater than half of those costs for the erstwhile family unit!

@Alan S (#17):

Re: “One reason for this ….”

Page 64 onwards of this paper from 2014 may be of some interest:

https://www.royallondon.com/siteassets/site-docs/media-centre/cazalet-consulting-when-im-sixty-four.pdf

@Al Cam (#32)

While I’ve read that report before, it certainly contains a useful level of detail. There another report at https://www.wtwco.com/en-gb/insights/2017/07/how-does-a-bulk-annuity-provider-invest that is also interesting (bulk annuities appear to be an ‘exciting’ area of insurance!). I guess the point I was making that the range of investments with reasonably well guaranteed inflation adjustments to underpin RPI annuities is limited compared to those for nominal annuities (e.g., holding TIPS or other foreign inflation linked bonds doesn’t necessarily protect against UK inflation). On a very limited set of calculations (with various assumptions made about longevity), the underlying yield for nominal annuities appears to be greater than that of gilts by a larger amount than the equivalent for RPI annuities. However, this difference could be because of greater fees (fewer RPI annuities are sold).

One interesting test is to run moneyhelper to obtain a quote for a single life RPI with a 30 year guarantee period (currently 3.72% for a 65 year old) and compare this against what could be achieved with a 30 year ladder (payout rate of about 3.73% for a gilt yields of 0.8%). Of course, the annuity provides income beyond 30 years. Doing the same thing with a level annuity and nominal ladder one obtains 5.96% and 5.62% (gilt yields of 4.1%). In other words there is currently a slight premium for building a 30 year nominal ‘ladder’ (i.e., an annuity with 30 year guarantee period) through an insurer than self-constructing it from gilts, while for the equivalent RPI ladder there isn’t.

@Alan S:

Thanks for the link , which I will peruse in slower time.

That is an interesting calculation, which on the face of it comes to the same conclusion (in terms of VFM of level vs index linked annuities) that Ned came to nearly ten years ago.

IIRC, there are nothing like enough [inflation linked] gilts in the market to satisfy the overall demand. Thus, life insurers, DB pension funds, etc have to use other instruments.

@Alan S (33) Your analysis comparing gilt ladders against annuities with a 30-year guarantee is fascinating. It surprised me that with such a long guarantee period the level annuity still beats the nominal ladder and even the inflation-linked annuity is very close to the linker ladder. As the guarantee period effectively eliminates mortality pooling for that duration, it shows that annuity providers do indeed invest in many more instruments than government bonds.

@Al Cam (31) Thanks for encouraging me to read the Blanchett & Finke paper. They certainly seem to make the case that having guaranteed income is a potent force for spending compared to drawing down from a portfolio. I’d almost be tempted to annuitise some of my SIPP to test the theory on myself, except that with tax thresholds currently frozen until 2028, and with my unsheltered assets currently throwing off more (non-guaranteed) income than expected, I don’t want to shoot myself in the foot by entering the HR tax band in two or three years. Although a linker ladder would generate a comparatively lower tax liability than an annuity, I don’t think it would quite cut it psychologically. The income would be guaranteed but its infrequent and somewhat irregular arrival would make it more like investment income. It would not have the same psychological effect as a pension or annuity’s monthly payment into your bank account.

@DavidV:

Glad you found the paper an interesting read. Some of the numbers do seem quite eye opening. Having said that, IMO some of the caricatures they sketch are a bit simplistic, for example they seem to state that a person with a high risk tolerance is unlikely to underspend in retirement. Well, we can both think of at least one exception to this.

Fiscal drag IMO is insidious. Fortunately, you are alert to its creeping corrosive nature. The best I think we can hope for is a change of heart at no.11; but I would not bet much on that happening any time soon!

Merry Xmas.

@DavidV (35). When I first did it, I also found the comparison between a ladder an annuity with long guarantee period an interesting one and the result surprising. I also note that, as well as other instruments in their investment pool, one of the other things that insurance companies can do is (at least partly) offset annuities against life insurance (my understanding, is that overall value of life policies is significantly larger than annuities). There’s a section in Pfau’s book (Safety First Retirement Planning) on the details of costing life insurance , albeit from a US perspective, that I’ve never been sufficiently motivated to explore further.

As you mention, tax is a consideration (usually neglected in general academic calculations because there are so many possible permutations). I do note that the fact that capital gains with a ladder are free of tax actually means that it might be better constructed in a GIA rather than a SIPP. If I understand it correctly, this also applies to an annuity if purchased using funds from an already taxed source (the so-called purchased life annuity) rather than a SIPP, since only the interest component of the income is then taxed (although I note that the payout rates for PLAs are lower than for regular annuities). However, while I might be wrong, I don’t think PLAs are offered with RPI option.

@Alan S (37) Tax considerations do indeed put considerable constraints on decisions of what investment instruments to use in which accounts – all the time trying to be mindful of the old adage of not letting the tax tail wag the investment dog. As acknowledged in (29), linkers’ exemption from CGT and the low coupons of most, means they are best purchased from unsheltered assets. You make a good point about PLAs having similar advantages of lower taxable income as much of it is deemed as return of capital. One problem is that it is difficult to find much information on PLAs, such as the current rates and the portion deemed taxable. I also don’t know if inflation-linked options are available.

As ever, I think the decision comes down to psychology. Any assets in a SIPP are going to be taxed eventually when extracted, whether as drawdown, lump sum or pension annuity. It is one thing to defer this taxation while trying to construct a lower taxable income from unsheltered assets using gilts. It is another to make the irreversible decision to annuitise unsheltered assets and leave the SIPP untouched (I’m speaking here as someone with no dependants to leave a legacy to).

I think it is common for annuity providers to match their annuity liabilities against the complementary liabilities of their other books. My small annuity happens to be from Just Retirement, who are also providers of equity release products. It is no surprise to see in the Cazalet report linked by Al Cam (32) that a major portion of their annuity book is backed by equity release. I’m not entirely sure how the liabilities of each book complement each other. Presumably long-lived equity release customers generate more profit from rolled-up interest payments, while short-lived annuity customers are obviously more profitable. I’m not sure how the cash flows can match though.

Awesome article, wonder if you guys came across this paper and talk Challenging the Status Quo on Lifecycle Asset Allocation , where paper argues that being in 100% stocks is better even in retirement, curious if you have any thoughts about it or even an article would be great to read.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y3UK1kc0ako

thank you

@ramzez (#39): Somewhat similarly, over at “the7circles.uk” (part 2, 7th Circle, point 6) for dynamic asset allocation they recommend 60% equities at retirement “rising to 100% equities as the best glide path, especially when starting at a high CAPE”. Sequence of returns risk matters less & less as there are progressively fewer years of retirement to finance.

@TA, et al

Re: “(Though it’s interesting/alarming to note index-linked annuities are no longer available in the US.)”

This post may be of some interest:

https://howmuchcaniaffordtospendinretirement.blogspot.com/2023/12/fixed-dollar-spias-vs-fixed-rate-cola.html

@Al Cam (41) In any US-based discussion of annuities it always strikes me that their annuity rates are consistently higher than ours, even though I understand that interest rates are already beginning to come down there.

It did strike me as a rather strange article. ‘Bill’ decides to assume future inflation at 3% p.a., yet chooses to compare the PVs of a level annuity with one with a 2% annual escalation. (Why not a 3% escalating annuity?) In both cases he needs to retain some of the early income to invest (in risk-free investments) to provide the shortfall in later years. Under his inflation assumption he could have eliminated this need by choosing a 3% escalating annuity. In calculating the PVs he assumes a discount rate of 5%. He concludes that the 2% escalating annuity provides better value based on its PV compared to the level annuity. Of course, assuming a different discount rate would provide a completely different result. I wonder who is more skilled at selecting appropriate discount rates – ‘Bill’ or the annuity provider? It is credible, though, that the escalating annuity does indeed provide better value for those who achieve or exceed their life expectancy. The lower initial payout will provide more mortality credits from those who die earlier.

I freely admit that choice of discount rate in time value of money calculations has always confused me. Sometimes they seem to be based on assumed inflation, other times on assumed returns available on alternative investments. Presumably in this case it is based on a risk-free investment with assumed 2% real return. Is this realistic?

@DavidV:

Re US vs UK annuity rates, I tend to agree but could only speculate as to the underlying reasons.

As seems usual in a lot of these types of calculations, the method appears sound but the detailed parameterisation is rarely explained/justified.

I tried to locate the Joe Tomlinson work mentioned (the source of the 2% escalating annuity pricing) – but unfortunately had no success. I suspect Joe did not provide pricing for a 3% variant.

There is a “contact us” button on the blog page and from what I understand Ken is usually quite responsive.

I recently tried to find an IFA to help buy a fixed term annuity froma SIPP but none of then (i approached 10) would do it without a full and very expensive financial review (none willing to do execution only) so this analogy feels spot on.

“To make a health sector comparison, it is as if medical advice could only be given by leading (and expensive) Harley Street specialists who were required by law to undertake a full range of head-to-toe checks on the patient (CAT scans, eye tests, auditory perception, blood analysis, lung performance, metabolic rate, liver function etc) and carefully consider all of these before, say, removing the patient’s tonsils or prescribing cream for eczema.”

Cazalet Consulting: When I’m Sixty-Four (September 2014)

https://www.royallondon.com/siteassets/site-docs/media-centre/cazalet-consulting-when-im-sixty-four.pdf

PS Someone suggested I create a gilt ladder instead but although I’ve learned a lot from this article this was way outside my expertise/comfort zone

@Snowcat – I think maybe you’d be fine if you went through an annuity company rather than an IFA?

It’s possible the regs have changed since I did it, but I was able to get annuity quotes for my mum a decade or so ago without going through a financial review. I got quotes from:

https://www.sharingpensions.co.uk/

https://investmentsense.co.uk/

https://retirementsolutions.co.uk/

@TA

Thanks. We had been told that an IFA could get a better deal (after paying their fee) than otherwise or going direct. In the end we went through Retirement Line, a broker, who were very efficient and professional. Their quotes were much better than on Moneyhelper etc despite their commission (about 1.5% of the pot)

“FWIW, I recently made a tool to build gilt ladders, https://lategenxer.streamlit.app/Gilt_Ladder , supporting both indexed and non-indexed gilts. I made this because I too am considering using gilts to fund certain short / medium term liabilities.”

I wanted first to add my thanks to @LateGenXer for this incredibly impressive piece of work. A real public service! One question – does this still allow you to use index gilts ? I could only see nominal gilts.

Secondly I think there is lots of room for an article comparing ladders with fixed term annuities. Since a year ago annuity rates have improved further and I chose an 8 yr fixed term annuity (with full term guarantee period) to bridge an income gap to state pension age. I also used this tool to look at how the costs compared to a (nominal) gilt ladder constructed to give identical income and found the gilt ladder was dearer for annual payments (1%) and only slightly cheaper for monthly (0.5%) cf annuity. This was despite holding the ladder inside a SIPP with no tax to pay before withdrawal, and a 3.25% cash interest rate. Of course SIPP platform fees then make it even dearer.

This surprised me as a poster on another forum urged me to look at gilt ladders and suggesting it would be cheaper. I think someone above pointed out that that this may not be the case and my experience seems to bear this out.

Ramin on Pensioncraft video gives a stark warning about ‘egregiously high fees’ on annuities as an argument against them, but I think this now looks misleading and overly negative.

So the question I have is – if a FT annuity can give more income than a gilt ladder, with the same zero risk, why would you go for the latter with all the hassle of setting it up, manually transferring out the income 12 times a year, etc etc? I guess you can always abandon your ladder but at an unknown cost but is that worth the cost?

@snowcat – if you die the annuity money is lost and the insurance company wins. Gilt ladder – you can pass on to your beneficiaries. That is my take on it.

@snowcat

I’m glad you found the tool useful.

> One question – does this still allow you to use index gilts ? I could only see nominal gilts.

It does: left-hand side bar, towards the bottom, “index-linked” toggle button.

> So the question I have is – if a FT annuity can give more income than a gilt ladder, with the same zero risk, why would you go for the latter with all the hassle of setting it up, manually transferring out the income 12 times a year, etc etc?

There’s no free lunch: all the extra income an annuity gives over a gilt-ladder comes from the chance you’ll die early and end up paying in into the pool more you you than took out. The more likely you’ll die earlier, the cheaper it gets. The more likely you’ll stick around for the whole term, the more closely it will match the ladder, minus fees, of course.

So if you want to maximize income and don’t care to leave a bequest, annuities should beat an gilt ladder.

These are not the only two choices though: for those not risk averse, it should pay off remain invested in the equity market for and defer an annuity purchase to later in life, when payouts are higher.

FWIW, I wrote some thoughts on annuities on https://www.reddit.com/r/FIREUK/comments/1fz9o0e/wear_sunscreen_and_buy_an_annuity_in_your_80s/

Thanks for the replies @Mr H and @LateGenXer

The fixed term annuity we took has a guarantee for the full 8 year term so it continues to pay out the full amount of the monthly annuity for the whole term to the named dependent in event of death. Hence no chance the annuity provider will win on this one.

Taking the FT annuity now fills the income gap for my wife between now and the state pension when it’s most needed, and more reliably than a ladder. And given there is no income penalty (and even a bonus) this seemed clearly the best solution.

In terms of potential bequests the Reeves budget put paid to the plan to leave the SIPPs to children as they will now almost certainly be caught by IHT.

Will have a read of the reddit post

PS After I pop my clogs my wife will get a good NHS survivor’s pension and also inherit my own SIPP which she can annuitise or drawdown at a lower tax rate than I would pay to take it.

My age (71) means I’m clearly well past the FIRE demographic and some of the comments look pretty funny to me now (’80 is incredibly old’)

@snowcat

> The fixed term annuity we took has a guarantee for the full 8 year term so it continues to pay out the full amount of the monthly annuity for the whole term to the named dependent in event of death. Hence no chance the annuity provider will win on this one.

Interesting — a fully guaranteed fixed term annuity — it’s indeed a gilt ladder in all but name. If they don’t use mortality credits then I don’t see how providers can price it more cheaply though.

I went to https://www.legalandgeneral.com/retirement/pension-annuity/pension-annuity-calculator/ , and entered 65 y.o, £133,333 (so it’s £100k after 25% TFC), and the figure I got for “Guaranteed income for a set period, Cash-Out Retirement Plan” with 10 years is £12,150/yr.

For a non-index-linked ladder, https://lategenxer.streamlit.app/Gilt_Ladder is giving me today £81,341.75 for £10k/yr, which normalized for £100k purchase cost gives £12293/yr.

So, assuming I made no mistake, taking L&G quotes at face value, they would be charging £143/yr (around 1%) for the hassle of setting up the ladder. Not exactly a low fee, but not high way robbery either.

“There’s no free lunch: all the extra income an annuity gives over a gilt-ladder comes from the chance you’ll die early and end up paying in into the pool more you you than took out.”

I think I have to challenge this based on what I have learned for the like for like comparison, the extra income from the FT annuity must come from the better returns the provider can achieve compared with gilts.

@LateGenXer

Just for info, our quote was on a £125758 pot (before TFC), £94319 (after TFC), age 58, and the L&G calculator gives £13800 pa on a 8 year term (which is very close to what the broker got).

The non indexed gilt ladder cost for the same monthly income is £93979 depending on starting date (this is 28/1/25). If i have use it right!

So in gross terms the ladder is £330 cheaper (41 pa). But the ladder would also have SIPP platform costs (8 years capped at 120 for me) plus buying costs for 18 gilts (90) which then turns it around to make the ladder much dearer (I reckon by approx £820 total = £102 pa). [Taking the sum out of the SIPP into a GIA would incur a hefty income tax bill I presume. ]

> Interesting — a fully guaranteed fixed term annuity — it’s indeed a gilt ladder in all but name. If they don’t use mortality credits then I don’t see how providers can price it more cheaply though.

I have read elsewhere that insurers can and do get better returns from instruments other than gilts. Maybe with some risk, (but they don’t seem to price that in to customers amazingly)

Anyway my conclusion -which I think you share – is that annuities should not be dismissed out of hand because of historic prejudices. It also seems most people (even those who are generally up on finances) are unaware of fixed term options and they definitely deserve to be considered more along with drawdown options.

@snowcat

Right. I’m not averse to annuities in general — they are an unique mean to get those mortality credits and hedge against long lifespan. These guaranteed FT annuities are a completely different (and novel) beast, but they don’t look a bad deal neither: I wouldn’t recommend a gilt ladder to an ordinary (non-confident-investor) person, but a well priced guaranteed FT annuity does look like an affordable and hassle free proxy.

Regarding annuity provider profit, I also heard about insurance float, but I thought it applied to much longer investment horizons. It’s not my area of expertise — you might be right.

Definitely not my area of expertise either! The comments on another board were ” insurance companies are investing in corporate debt with higher yields than gilts (as well as other more exotic instruments) and have economies of scale and can offset their annuity business against their insurance business” And “insurers hedge interest rate and inflation risk using derivatives to a varying degree with only some physical gilts/ILGs. Most of the rest is in corporate credit for the yield spread plus some other matching longer dated secure assets (often illiquid but that doesn’t tend to matter). The yield pick up from all these accounts for the better rates over and above a gilt ladder.” Sounds plauible I guess.

And a month ago I wouldn’t have known one end of a gilt ladder from the other – now I would feel reasonably confident if it fitted the bill.

@Snowcat – I missed your reply on 14 November. I’m glad you’ve found a good solution. My thanks to you and LateGenXer for the ongoing exchange, too. I need to write a Monevator series on annuities, so this is all very interesting to me. I don’t remember anyone mentioning annuities as a tactical bridge to the State Pension before.

I also agree with both of you that annuities have had an undeservedly bad press.

I was going to mention that an annuity company entails credit risk vs gilts but that doesn’t actually appear to be the case as the FSCS offers annuity protection at 100%.

Thanks TA – I will be very interested to read that series.

It’s clear that most people still think of annuities as meaning lifetime and are unaware of fixed term products, or how they are now much more generous than a few years ago. The addition of a guarantee period (on either lifetime or FT) also mean that the risk of losing the investment due to premature death can also be minimised or even removed – at surprisingly low cost. This means the monthly payout continue to your beneficiary. This is more generous than the ‘protection’ option which just pays out a lump sum of pot invested minus payments made. These should help with the psychological barrier of handing over a large sum of money and worrying about mortality risk

I have discovered that even a lifetime annuity can come with a guarantee period of up to 30 years, so this becomes income guaranteed to survivors. I assume that this may however get assessed for IHT following the Reeves changes (consultation still ongoing?)

While on the subject of annuities, I had often seen it said that an IFA can get a better quote than a broker or going direct to the insurer (not all insurers let the public do this but some do). The IFA usually takes their fee separately – I was quoted 1% of the pot; the broker takes commisson from the insurer (only revealed later – often 1.5-2%). IFAs are (since RDR?) no longer allowed to accept commission payments although they will if asked just take their fee before the purchase of the annuity – but that clearly reduces your payments.

Having just obtained figures for a lifetime annuity on my SIPP pot I can confirm this.

The IFA takes their 1% fee separately but their annuity rate was still 1.3% higher than the broker’s.

The reason for doing better than going direct is said to be that the IFA has access to the insurer’s Zero Commission rates but Joe Public doesn’t, so the insurer just keeps the commission themselves in this case.

So top tip – try to use an IFA on an Execution only basis and agree their fee first. The problem is finding an IFA who will do this. As i said in an earlier post I tried 10 but only one would. The others wanted to do full a financial review (fee – ‘it depends’) or charge a minimum or 2 or 4k. It seems most IFAs want fees from ongoing portfolio management and annuities are not that lucrative. The usually advertised sites as sources for IFAs – Unbiased and VouchedFor – were useless and packed with corporate and expensive ‘wealth managers’ who can pay these registers the big fees they charge for being on them. I found the IFA who agreed through a local search and he seems to get business on word of mouth. A good sign

It’s a shame that financial advice has been priced out of reach for the average punter, but that’s another story

I thought I ‘knew’ that an index-linked gilt ladder lasting 3 years was a guaranteed solution to my problem, but having read the above and a couple of other related Monevator articles I’m now uncertain.

I have accumulated 75K (after expected tax from a dealing account with a world tracker) to fund my grandson’s uni expenses. He starts in the 2029 academic year. All this stuff about volatility and so on, above, confuse/concern me!

Does this mean a 3 year index-linked gilt ladder, purchased soon, could/should ‘guarantee’ the equivalent of 3 payments of 25K’s inflated equivalent in 29, 30, 31?

Do market forces, including the current state, and/or interest payments make a substantial difference to my aspiration?

@Jerry W – a ladder of 3 index-linked gilts that mature successively in 2029, 2030 and 2031 will do exactly what you want – provided you hold them to maturity i.e. don’t sell them before they mature / redeem.

If you purchase them, then check their market price in the meantime, you will see volatility i.e. gains and losses. But you can safely ignore it. Provided you hold to maturity, then each £25K tranche will return your £25K investment, plus inflation, plus the real yield-to-maturity on offer when you purchase.

Nothing about the state of the market etc should concern you – the outcome is a mathematical certainty. We could talk all day about edge cases like government defaults or deflation etc but this is all vanishingly unlikely.

Ideally, you’d hold your linkers in tax shelters. Although gilts are capital gains free, they are taxable on interest as usual. Inflation-adjusted interest is also taxable. That would matter if your index-linked gilts are held in taxable accounts and we suffered a great deal of inflation in the meantime.

Here’s the line up:

T29 – matures March 2029

T30I – matures July 2030

TR31 – matures August 2031

Thank you. As I get into your well-documented spreadsheets more, into DMO’s documentation, especially regarding the Index Ratio, and remembering stuff from a bond position keeping system from 30 years ago, I feel increasingly confident in what I’m intending doing.

@Jerry W — Glad TA’s answer was helpful, and good luck with your position. Please remember we aren’t authorised to give personal financial advice, so please do continue to do your own research and, as you say, reach your own confidence in your actions. 🙂

@Jerry W – bear in mind – you have to reinvest the coupons to get the yield. Your yield will be less if you don’t, and will vary anyway depending on the prices you reinvest at over time.

Yes, I don’t take it as financial advice; no worries.

Yes, I’m getting to grips with the instruments and the spreadsheet, its uses, how it relates to my situation and so on – e.g. realising I’m buying ILGs today for redemptions some years in the future; I am pretty much ready to try an experiment of pretend buys using the latest index ratios and dirty prices and see what I will(?) get in 2029-31 (in terms of today’s £ aka real value).

There’s a 2030 issue here.

The issue is the planned alignment of the RPI which dictates payments on over £620 bn of ILG with the lower CPIH methodology for housing costs from 2030.

Since RPI has historically run 0.8%-1% higher than CPIH, this change is projected to save HMG and cost ILG holders ~£6 bn p.a. in debt interest and wipe an estimated £90-100 bn off the value of the relevant bonds.

The crucial financial and legal battle came when 5 major pension funds, inc. those for BT, M&S and Ford, sued HMT.

They argued the change was an unlawful act resulting in a 4%-9% avg. reduction in lifetime benefits for 10.5 mn people in DB schemes whose retirement income is linked to RPI.

The funds argued the change was a transfer of debt burden from the state to the pensioner.

Unfortunately, the High Court ruled in Sept 2022 that the change was lawful, affirming the gov’s authority under the Statistics and Registration Service Act of 2007.

For small investors holding ILGs through retail products (e.g. ILG funds or ETFs), the reduction in value post-2030 is to a large extent already embedded in market yields.

But for investors seeking protection against their actual cost of living, ILGs become a less effective hedge.

RPI, though flawed, tracked a basket closer to household spending (especially mortgage interest costs and housing). CPIH is lower running and excludes some of those pressures.

In practice, CPIH will under compensate relative to actual experienced inflation, particularly in periods of housing cost spikes or mortgage rate volatility.

This makes ILGs less attractive as a pure retail inflation shield. Despite the switch, long duration ILGs still play a role as assets that tend to rise in price when real yields fall (hedge against deflationary shocks).

But their role as a robust retail CoL hedge has for me been badly compromised.

IMO investors may need (at least after 2030) to combine them with other inflation sensitive assets (e.g. commodities, infrastructure, or even equities with pricing power).

Moreover, I think that if other jurisdictions (e.g. US TIPS) retain stronger inflation linkage, then they could become relatively more attractive inflation hedges for us in the UK.

And a final point. HMT having screwed over ILG holders on RPI once – what’s to stop them doing it again, given the court ruling?

@TA #61 still getting my head around ILGs. Re your example:

T29 – matures March 2029

T30I – matures July 2030

TR31 – matures August 2031

You say: “ If you purchase them, then check their market price in the meantime, you will see volatility i.e. gains and losses. But you can safely ignore it. Provided you hold to maturity, then each £25K tranche will return your £25K investment, plus inflation, plus the real yield-to-maturity on offer when you purchase.”

Parking the 2030 issue, does that not depend on the price you buy them at given the volatility between the issuing of the ILG and its maturity? In other words if you buy them at a premium mid-term you only get back the nominal (not what you paid) plus coupons & inflation adjustment etc?

Happy to be corrected.

Hi – just following up on my post #67 as nobody commented. @TA #61 still getting my head around ILGs. Do you have a view on my possible misunderstanding in #67?

@Ian,

At any instant, the quoted price/yield of any bond fluctuates. When you buy a bond at a given price/yield, you’ll _fix_ that return provided you no longer transact, and hold to maturity. This is because all future cash flows from therefore are fixed.

For ILGs, you’re fixing the returns in real terms (RPI adjusted.)