What caught our eye this week.

Hello campers, TA here – standing in for TI, who’s off on his annual hols this week. That means topping up his monitor tan in some seedy foreign hotel instead of his seedy London lair. Ah well, a change is as good as rest as they say.

Right, with that piece of libel out of the way, I understand there’s a big event coming up on 4 July that simply cannot be ignored. That’s right, my assault on the Bitchfield pie-eating record. Oh, and this news just in: there’s a General Election on, too.

So as reluctant as I am to spend all day fighting fires in the comments section, I can’t rightfully ignore the political earthquake incoming.

Personally, I chart a wavy political line: weaving around the traffic cones of the centre ground.

I’ll happily borrow my opinions and remedies from the sane of the centre-left and centre-right. My vote goes to whoever I think will best govern in the interests of the whole country.

In 2010, I felt Labour could do with a spell in opposition. They needed time to think again.

So here we are in 2024 and we’re faced with a choice: more of the same or time for a change?

As ever, it’s Red vs Blue.

But governments shouldn’t be judged like football teams … “I’m Accrington Stanley until I die,” or whatever.

Governments should be judged like football managers: on their track record.

Why as citizens would we offer politicians our unconditional support?

Either they put the country on a sound footing and create the necessary conditions for prosperity, or we turf them out.

It’s the only leverage we have. If you’ve done a bad job, you have to go. And, my god, have any of the country’s problems appreciably improved over the last 14 years?

- Low productivity

- Economic competitiveness

- Public services: NHS, social care, education, welfare

- Housing

- National debt

- Immigration (interpret this according to your political taste)

- Regional imbalances

- Environmental protections

How about the two big promises of the last election: Brexit and Levelling Up?

Whatever you think of those two issues, it’s telling that the Conservatives aren’t shouting about their achievements on either count.

They haven’t got a vision beyond staying in power: witness ad hoc policy gimmicks like National Service. Tories were pooh-poohing that idea only weeks before the election was called.

They’re afraid to take difficult decisions to solve the country’s problems: hence the lack of progress on planning reform or social care.

And now they’re laying traps for the next Government by ruling out every tax rise they can think of. The objective being what? To keep the country in a mess until we fall back into their arms? Love it. Essentially, they’re saying: “If we can’t have you, nobody can.”

This from the people who gaslit us with ‘fiscal drag’ – raising the UK tax burden to its highest level since 1950, while simultaneously claiming they’re cutting taxes because they’ve knocked a few quid off National Insurance.

Not to mention the chaos of four prime ministers in five years – at least one of whom was manifestly unfit for office.

Casting a vote for this lot again is like going back to a bad boyfriend who says it’ll be different this time.

You may doubt Labour. “All politicians are the same,” is the cop-out defence I keep hearing. Well, let’s find out shall we?

The ire of the electorate should be biblical. Not because ‘beating the Tories’ is an inherently good thing. But because all politicians need to know that if they screw us around, they’re out.

That if they spend their time spinning and lying and fudging and faction-fighting instead of mending and sorting then they’re goners.

Remember how Boris Johnson’s 80-seat majority was meant to be unassailable? He was being talked about as a two-term prime minister because Labour needed an impossible swing to overturn their historic 2019 defeat.

Thankfully those political assumptions are in the shredder. Unquestioned party loyalty is breaking down. Tribalism is dissolving.

So, if Labour get in, they’re on notice. The electorate is volatile and vengeful.

That’s how it should be.

Some may still be stuck in the trenches, unable to overcome their fear of the Red team. But in truth, neither of our two main parties are radical. They’re usually only elected when the moderates are in charge.

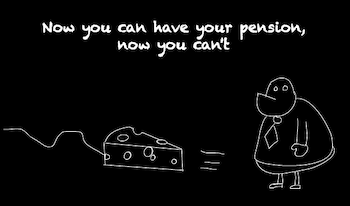

Can things only get better? Definitely not. But tribalism doesn’t help us. It’s the political equivalent of auto-renewing your subscription. You will be taken advantage of.

So it’s time to switch supplier. I’m not expecting massively better service just because I’ve moved from EDF to E.ON or whoever. But it’s the only way to keep them both in line. Hence, I say:

- Vote tactically

- Vote on record

- Do not reward failure

Have a great weekend.