I can’t think of a much trickier in-tray than that facing governor Andrew Bailey at the Bank of England right now.

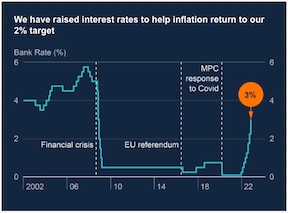

The institution he runs just hiked UK Bank Rate by 0.75% to 3% in the biggest jump for three decades.

And nobody is very happy about it.

“Too much too soon!”

“Too little too late!”

Everyone could do a better job than Bailey.

Never mind that just a month ago the Bank had to intervene directly in the market to stop a liquidity crisis in gilts cascading into the banking sector.

A mini-crisis manufactured overnight by wonks, that took less than a week to blow up.

And never mind – as many now seem to forget – that less than three years ago we faced a depression had not governments and central banks alike acted to offset the economic hit caused (unavoidably) by Covid and (perhaps over-egged) by repeated lockdowns.

Just look at where this interplay of fiscal stimulus, near-zero interest rates, economic inactivity, Brexit, and the shifting demand for goods and services has put us:

- Consumer price inflation – 8.8% (6.8% above target)

- GDP – minus 0.3% (recessionary)

- Unemployment – 3.5% (the lowest since 1974)

- Average house price £296,000 (an all-time high)

- Average five-year fixed mortgage – 6% (highest for 12 years)

- GBP/USD – $1.12 (down 15% over five years)

- Number of UK chancellors since July 2022 – four (careless!)

- 10-year gilt yield – 3.5% (up 250% since the start of the year)

It’s a cat’s cradle of contradictory indicators – and it could have been worse.

Truss and Kwarteng: gone but not forgotten

In the wake of the Truss and Kwarteng mini-budget show (parental discretion advised) the market briefly expected the Bank of England to have hiked rates by as much as another 2% by now.

That fear saw banks scrambling to raise their mortgage rates, if not pull their products altogether.

Thankfully the decapitation of the Truss regime saw new chancellor Jeremy Hunt undo a lot of that damage. Rishi Sunak as prime minister has further soothed frayed nerves.

It now feels like a bad dream. We still got the same 0.75% interest rate rise that we expected before Liz Truss had ever said she’d never resign for the first time.

Except that like in some horror movie where the relieved victim wakes up from a nightmare only to discover their cat impaled on a candlestick in the living room, those higher mortgage rates have yet to drop back to where they were.

Partly as a result, some pundits now forecast house price falls of 10-15%.

And if you think that’s not so bad – overdue if anything – then be careful what you wish for.

So long and thanks for all the cheques

Because just as one does not simply walk into Mordor, one does not simply repeatedly hike rates, play musical chairs with prime ministers, and ding the housing market without consequences.

Sure enough, the Bank of England has got even gloomier about the economy.

It already thinks a recession is underway. And its chart now suggests the pain will last for two years:

Source: BoE

The good news is the Bank’s central projection is for a shallow recession, albeit an overlong one.

The better-but-not-exactly-news-news is that – contrary to what many people now protest – if the Bank and politicians hadn’t acted in 2020, then that plunge in GDP (orange line) would have taken far longer to bounce back.

In other words, the pain we’ll suffer soon is to pay for what we avoided back then.

The Bank of England governor under fire

For me, inflation continues to be the truly perplexing puzzle.

Some left-leaning rabble-rousers economists pitch the BoE as raising rates simply to mete out justice:

According to this fellow, Andrew Bailey actively wants to put millions out of work.

Obviously I don’t see it that way. Because I am a grown-up.

Nevertheless there is something perverse-seeming about raising rates even in the same breath as you forecast a two-year recession.

And I find the issue even more vexing because I’m seemingly one of the last people who still believes (perhaps being biased, having predicted it) that it was mostly the economic disruption caused by the pandemic and repeated lockdowns 1 – rather than solely excessive monetary and fiscal stimulus – that’s behind most of this inflation.

But whatever the origin story, at least inflation is forecast to start falling sharply, and soon:

Source: BoE

With a fair wind and/or a bit of luck (peace in Ukraine, say) the inflation shock could be abating by the middle of next year.

More likely we’ll need to wait until early 2024.

Another chunky crumb of comfort is that the Bank of England baked a 5.25% terminal rate for rates into its macro projections.

But that 5.25% was informed by our brief dalliance with Trussonomics, and it shouldn’t come to that.

The peak in rates now is expected to be 4.75%.

So bad it’s almost good

Nevertheless on these figures as published, the Bank of England expects unemployment to climb above 6% by 2025.

Which will be miserable for anyone who loses their jobs – especially if house prices do start to fall sharply.

Indeed it’s not hard to see the potential for a fresh ‘doom loop’ where forced selling meets negative equity to make a bad situation even worse.

Think early 1990s, only with social media.

All of which is also what makes investing especially tricky at the moment, incidentally.

I’ve been getting more bullish for a while, partly because I had judged that market expectations for US rates were peaking.

But this isn’t a sunshine and roses view. Rather it’s because I think rising mortgage rates in the US have already done enough to throw that nation’s housing market into a funk.

It’s a similar story in the UK – albeit more Monty Pythonesque thanks to our political backdrop.

For me it’s a reason to avoid entirely abandoning those hated growth stocks, and to be wary of overloading on the cyclical value-style shares that have done so well since the end of 2021.

My hunch is the worst of the valuation compression is behind the growth companies, while at the same time the economic outlook is deteriorating for cheaper but less exceptional firms.

As for passive investors, no reason not to keep on trucking of course.

At least your bonds will be increasingly throwing off useful income.

Bailout Bailey?

As recently as December 2021, Central Banks didn’t think inflation would get so high, nor that they would have to raise interest rates by very much.

Low and slow was the forecast back then.

I can understand why central bankers feel they have to act tough now, given how wrong they were. But I also think a sharp pivot is increasingly more likely than not, as the cumulative effect of all this tightening adds up.

Personally, I see stagflation threatening to turn into mild deflation as becoming more of a risk than runaway inflation.

But it doesn’t have to end so bleakly either way. We could yet muddle through.

As anyone who saw the Lord of the Rings knows, it turned out you could simply walk into Mordor.

So perhaps Andrew Bailey similarly can raise interest rates, slow the economy, and then pull us up out of the descent before we dive into a really deep decline.

But I’d rather him than me.

- And latterly war, which I didn’t foresee![↩]

Comments on this entry are closed.

The biggest problem with the CPI inflation fan chart is that the projection part (which IIRC apparently covers 90% of the modelled outcomes i.e. not the full story) has basically been telling the same story for well over a year now; whilst the reality line just keeps on climbing. Thus, the projection may look pretty but has IMO very little credibility now.

Amusing (sort of) to look back at the BOE’s Nov 2021 report (i.e. a year ago):

“In a nutshell … we expect inflation to rise to around 5% in the spring, but then fall back….we expect interest rates will need to rise modestly to return inflation to our 2% target”. At that point, BOE was predicting a base rate of 1% for today (i.e. Q4 2022) instead of the correct 3%! And for 2024 they predicted 1.1% (yes well…let’s see).

My lesson (if not already learnt) is this: Don’t believe BOE projections!!

Something really is deeply wrong when interest rates of 3% are seen as a dire calamity. I paid more than that for my entire mortgage career. I’m not using that to start the Four Yorkshiremen sketch, merely to illustrate that interest rates of half the historical UK medium-term average are not high in the wider picture.

This isn’t just the covid-19 or even Brexit, or the nightmares of a decaying lettuce. Much was never repaired after the GFC, and this seems to have impaired economic resilience in many parts of the economy.

Perhaps this is how money dies, simply being asked to feed too many dreams in too many places all at the same time. 3% interest rates are high in recent history, but are not high for Britain before the GFC – indeed 3% would probably be considered pathologically low before then. You don’t have to believe me – you can download historical bank of England interest rates from the Bank of England right here, back to 1700. People considering interest rates of 3% as massively high are more an indication that historically we aren’t in Kansas any more.

I agree with the points but there’s one thing in the last 6 months I would blame Bailey for. Not being forthright about Truss’ ideas being a non-starter during the initially leadership campaign. If Sunak could predict them in his initial leadership campaign, surely they could have too. I think his line to the press at the time was we don’t get involved – whatever measures the Government puts in place they will respond. Staying on the fence is pretty weak. I mean.. haven’t we learnt the lesson that if we leave an unviable option on the table for British voters to decide, they usually lap it up.

@ermine – agree with your sentiments. Having emigrated from a country where 8% interest rates were a norm, I find the gloom amusing. Dare I say, if families have been managing their finances just like the Government has – yes, there will be vulnerability to interest rate changes. But you have been more prudent it’s not a shocker by any margin.

Just to point out the obvious, its not the absolute value of interest rates thats the issue, its the rate of change in percentage terms in the upwards direction.

Thats the bit that is unprecedented and super painful.

I would imagine there is a strong argument to be made for impartiality from the BoE w.r.t political nonsense also..

I’d say that UK Prime Minister and England Football Manager are worse jobs than BoE Governor. The former of which attracts a far smaller salary than the latter.

> Thats the bit that is unprecedented and super painful.

No. It’s not. Imagine a stupid young mustelid, rocks up to buy a house. Interest rates are 8%, mid ’88. Yup. Have some of that. Sucker

“Hold my beer” says the Fourth Horseman, and gets on his horse. One year later, in October ’89, interst rates are just shy of 15%.

We’ve seen this movie before

@ermine — Yes, and average start prices were what c.4-5x earnings in the late 1980s, and that was peak London, versus, at least 11x today.

And also interest rates were 15% for about an afternoon. 😉

Of course you can say only an idiot would pay 11x earnings for their own home (and to be fair to you, you have said that over the years 🙂 ) but firstly, people who say that invariably already own their own properties in my experience (or have no feasible way of owning one at the other extreme) and secondly sitting out the market waiting for a correction back to what you thought was the trend can literally eat up a generation. (Been there, got several t-shirts from the several tours of duty…)

I’d also push back on the idea that something is necessarily ‘wrong’ with a rise to 3% interest rates causing pain.

Interest rates reflect demand for demand, and there’s been a glut of it for various big picture reasons (China, demographics, rich getting too rich and hoarding, arguably QE) for many years.

It would perhaps have been weirder if rates had been a more ‘normal’ 5% in such a world (well no, it would have caused a depression) given this backdrop.

But more importantly, the world normalized around the rates it was given and everyday people have had to go through their lives making decisions based on the cards they were dealt.

Of course some prudence is required, and nobody was forced to go hog wild on low rates. But a very ordinary couple in a very ordinary part of London buying a very ordinary starter flat have been stretched to their absolute limits — and required parental top-ups — for the best part of the last 20 years to buy their own home, for example. And in more recent years across much of the rest of the country, too.

We can say they shouldn’t have if they couldn’t afford mortgage rates doubling in a year, but owning your own home is a pretty standard part of life and you only live once.

Moreover, again, sitting out has been a hugely costly decision for most people. As I’ve said before I have friends who made just one big and brilliant financial decision in their life — buying a flat in the mid to late 1990s — who literally made at least half a million pounds out of it. It’s very hard to watch that recede in the mirror for one, five, ten, 15 years…

True, if there’s a reckoning now then we may both — after some argy bargy — agree that’s equally the way the cookie crumbles.

But I for one won’t be dancing around laughing at the folly of most of the people who got themselves into trouble.

Living a very normal middle-class life for people under 40 has forced very difficult choices upon them. And perhaps painful consequences. We’ll see. 🙂

Haha, that’s exactly what I was imagining, i.e. I was thinking of your housing narrative and the late 80s early 90s pain and comparing and contrasting in my head.

But this is worse right, in as much as we’ve just seen a tripling of rates rather than a doubling over a slightly shorter period, less than a year.

You watched ‘Scary Movie’, now we’re watching ‘The Shining’.

I was probably overcooking it with ‘unprecedented’ but I think this is another step up. the pain ladder than that era? Possibly I need to check the numbers though, maybe it is roughly the same? You still think same ballpark?

> I’d also push back on the idea that something is necessarily ‘wrong’ with a rise to 3% interest rates causing pain.

I wasn’t gaslighting what people feel as pain, that’s of course their experience. But the policy that normalised historically low interest rates and finacial repression in general were because the GFC was not resolved. It was bought out/appeased, and gave rise to unslayable monsters. Zombie firms consuming resources without returning useful productivity, asset price bubbles. And low interest rates – there wasn’t enough return on typing up capital. Those historically low interest rates were a symptom a a pathology.

I suspect we now get to pay that off in the aforementioned pain of some other sort. Or the money dies, in inflation, or capital is destroyed in war. The Beast of Capitalism seems to have to eat some of its children to find its way. If you arrest that, then you can put the unpleasant symptoms off, but you feed the monster, and it grows angry in the darkness, like the Id in Forbidden Planet, and its power to consume grows unseen, bcause it is starved of creative destruction.

> You still think same ballpark?

It’s difficult to say, because the higher absolute level of interest rates made it harder in a different way. Think about what say a 10% IR actually means – you’re effectively paying 10% of the capital value of the house just to stay still. At 3% that’s less bad, although of course the pathology is that absolute levels of the capital price go up. Having said that, a few years of 10% inflation can help with that no end – low interest rates and high inflation are a gift to mortgage-holders as long as they stay employed and their wages track up. My Dad bought his house outright on a blue collar wage earlier in life than I did because he say 20% inflation + for part of his mortgage-paying time.

I’m in a little bit of an uncomfortable position. My employer is still spending and hiring aggressively but simultaneously removing perks and signaling low expectations for annual reviews this coming New Year.

I’m staring down the barrel of a mortgage of 3.9x household gross income on a rate locked in for 5 years, back in May, at 2.7%. This is comfortable.

But by my estimation my income needs to increase by 5%/yr just to cover potentially increased mortgage payments come 2027 (assuming a 6% mortgage rate is obtainable then).

My vague plan at the moment is to just use the 5 year leeway to keep front loading my pension… before the government inevitably take away all the tax advantages. At least if I go bankrupt and can’t pay my mortgage my pension is protected.

Well the April 2023 CPI, and the 2023 recession shape, must be mostly down to how energy gets priced come April. What’s the middle path?

We’re just at the awkward point where rates have increased but home prices have barely moved. Borrowing costs up 80% and prices down all of 0.9% to October. I’d bet on rates decreasing again before home values fall 40% (albeit as someone with no skin in the game).

@ermine

It wasn’t high inflation in the 70’s and 80’s that was so good for mortgage-holders, it was the matching wage increases.

High inflation combined with low (or no) wage increases just adds to the cost of living without significantly reducing mortgage debt as a proportion of income.

Dave.

Surely inflation is on the rise not because the economy is blowing hot and there’s too much money but because of the escalating costs of energy and comodities. How will raising interest rates make a difference to these in any way?

@ Grumpy Tortoise. I’m of exactly the same opinion. The only solution I can come up with is that if we were to enter a global deep recession then pressure on those commodities would ease and prices come down. I feel that UK base rate is pretty irrelevant to global demands so no matter what the BoE come up with we’re going to be tracking EU woes + a factor for poor management, Brexit and the like.

I would like to say a big thankyou to Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng.

Without their political kamikazee economic strategy, the BoE would not have had a brilliant excuse to start the momentum of raising interest rates quickly. Now they have. Interest rates were going back to historic norms at some point, what better way than to have a PM and Chancellor heroically dive in between the decision and that first finger pointing bullet.

Now is the time to see who’s been wearing their swimming trunks in the sea or not…..

I’m certain there’s still time to buy a pair with some financial planning / buffering if you are feeling overexposed!

I have sympathy with those expensive houses, given the choice has been to buy an expensive house or spend a fortune on rent – especially in the London vicinity.

However, our institutions are largely to blame. The BoE could have raised rates many years ago; there was no reason to keep them so low for so long, unless the economy has effectively been dead for a decade. At the time of inception, ZIRP was meant to be a temporary, emergency thing, not BAU.

Also, the govt (and govts over the past 2o+ years) have gone all in to keep house prices high and pushing higher. Again, unnecessary and punishing the prudent.

On top of that, govt policy of recent years has been to hurt the incomes of the (now very) squeezed middle, with very high personal income tax rates at relatively low levels of income. One commenter here mentioned they need a 5% pay rise p.a. to cover expected future mortgage payments. More likely it’s a 10% rise to account for the tax man dipping into pay cheques.

So to stand still from a standard of living perspective is nigh on impossible for the employed.

Finally, QE is very much to blame for rampant inflation. Admittedly, the inflation has manifested in asset prices in the main, since the printing presses were turned on, but it was inevitable this would leak into consumer prices at some point. But ensuring consumers have no spare cash at the end of the month to consume, which is likely to be the case for the majority, given taxation and the cost of essentials, consumer inflation is likely to fall.

Interesting, and completely unsurprising given UK rates follow the US, that getting rid of Truss & Kwasi didn’t stop rates rising and also ensured economic growth is in the toilet for the foreseeable. Which is worse in my opinion than keeping “Trussonomics”.

Your point about people owning property commenting on house price multiples is very salient. If you say you think houses are overpriced and yet own property then either you are lying to yourself or knowingly making inefficient financial decisions which probably don’t qualify you to give advice.

The sheer importance of property to people’s long term financial wellbeing is hard to understate. I’m in my late 30s and first bought in 2011. Between savings on mortage vs rent and house price rises we’re easily £400k+ better off. House prices seemed ridiculous even back then yet they keep trending up.

@ Andy (#19):

Re: “At the time of inception, ZIRP was meant to be a temporary, emergency thing, not BAU.”

Really………..???

Just like the £20 pw rise to Universal Credit and look at the flack around trying to reverse that. IIRC, winter fuel allowance was similar. IMO best one of all was when Pitt the younger introduced income tax as a temporary measure in 1798 to help fund the war against Napoleon!

> The sheer importance of property to people’s long term financial wellbeing is hard to understate.

Well, I am the exception, and since every other bugger that screwed up with property is staying schtum on the subject in the face of the 95% who made hay on it I will do my bit for reminding people this isn’t a one-way bet. It nearly is, but if it ain’t for you, it’ll be the worst financial mistake you will ever make. I still loathe residential property with a passion and I don’t regard it as any part of my networth despite our host considering that irrational and bonkers. I have gone out of my way to make sure res prop is as small a part of my notional networth – no Rachmanesque BTL empire, second homes or all the property is my pension passions of my age cohort. I am of the view, to paraphrase Hunter S Thompson that “property is uglier than most things. It is normally perceived as some kind of cruel and shallow money trench through the heart of [the journalism industry] ^H^H^H^H British people of a certain age, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free and good men die like dogs, for no good reason.”

Unlike everyone else, I not regard buying a house as an investment in anything other than to keep the vile, loathsome and unregulated army of BTL landlords off my back. I had eight years of exposure to these bastards in my student and early working life. The experience was foul enough to make me ignore the sensible counsel of those around me, and perpetrate the worst financial mistake I ever made.

Before I get eaten alive by those feeling the forecast hurt of now, I acknowledge your pain, in no way do I deny it. I have seen the trailer for what may be to come.

Property was nothing but a blot on my financial wellbeing. Buying a house in 1989 was the worst financial decision of my entire life, and still is. It shat on my financial wellbeing such that it was only as an old git past the very end of my working life that I was able to afford the housing level of my erstwhile peers thirty years ago, by spaffing some of my investment gains on lifestyle inflation. As an investment property stinks for me, even 35 years after buying a house it’s not the largest part of my networth. Saving and investing knocks it into a cocked hat; I have made more money on the stock market between 2009 and now than I ever made on housing in 35 years, largely because housing was a twenty-year long misallocation of capital. The gory details are deconstructed here. Three million souls were hammered in that period, many lost their houses, the people either side of me were repossessed.

History never repeats, but it rhymes. The pathologies of now are not the same as those of that time. Hopefully there will be more compassion in the way the denouement is handled compared to then. I did manage to hang on, many others at the time didn’t. They had some advantages – the massive increase in the canker of an army of amateur BTL landlords propped up by tax-advantageous borrowing had to wait for Paragon bank’s launch of BTL mortgages in 1996 – as the instigator John Heron said on Paragon’s website

That was Not a Good Thing. Precisely why the following Labour government didn’t spike the guns of this bunch of BTL landlords front-running first-time buyers’ taxable income-paid repayment mortgages with tax-deductible interest-only mortgages beats me, but they didn’t. Which is why we are here with 11 times income multiples. Back in the day you had to actually be rich enough to own your Rachmanesque BTL rented out hovels, as opposed to being subsidised by government tax breaks (slightly attenuated by Osborne’s conversion) to screw younger generations out of their hard-earned.

You waffle too much to make this stuff useful, and worse, it is smug waffle (‘I predicted this and that’). To help you out, here are the salient points :

1) BoE have no policy tools other than interest rates, so that’s all they use (I suspect to justify their own existence)

2) Energy and food costs caused by Putin’s insanity are the root cause of this inflation, and will not be affected at all by central bank policy

3) Given 1) & 2) above, not easy to see why BoE ‘s actions can be considered as nasty and cruel punishment.

4) Bailey’s foolish/pessimistic pronouncements are completely out of order, and will probably become self fulfilling

Maybe you are not so grown up after all.

I am confused as to what the BOE do (and what deserves the massive salary for the governor).

Their (sole) job is to keep inflation at 2% +/- which they don’t really have control over and didn’t do hardly anything for a decade of ZIRP.

They don’t collect data – ONS do that – they don’t make policy decisions – what do they do?

And do they really have any control over either money, the economy or inflation? I doubt it.

@John G — Indeed. Here’s Tweet that sums up what those of us on the front line went through, albeit an extreme case!

https://twitter.com/JoshLachkovic/status/1588438057157533697

There are quite a lot of different factors at play here and organisations have different aims. I have concerns about the Bank of England functioning but can see the argument that they have only limited tools available to achieve the desired inflation outcome(s). They also have very little direct control over many of the various factors that lead to movements in inflation.

I personally think economists have an easy life as they are some of the few people that are perceived as ‘analytical’ but can change their minds/positions regularly and no one really ever holds them accountable simply because they have so limited control over many of the variables they are working with. It does make you wonder what they are contributing. Most people doing rigorous scientific modelling work or analytic forecasting are held to account against what later materialises in terms of actuals i.e. “the model said the 1 year outcome rate was estimated to be X, or some interval around X, and the 1 year outcome was Y”. Economists seem exempt from serious accountability that other modellers face simply because the assumptions that go into forming their X are so wooly and outwith their control that forecasts are changed continuously and so often that no one seriously expects them to be able to predict well much further than a few financial quarters at most. Fine, but lets acknowledge this for what it is.

Further, when almost your entire remit is concerned with an economy wide measure and largely ignorant (by design/intent) of how your actions will hit different subsets of the population, I can see how they are on a hiding to nothing and end up in perceived conflict with other organisations who do need to worry about levels lower than some economy wide summary measure. No reasonable persons will be high-fiving if the 2% inflation rate occurs within the next few years but tens or hundreds of thousands of people lose their homes, or society sees large unrest because of the impact on many *individuals* or specific groups of society. The Bank of England only indirectly needs to worry about individuals or subgroups, whereas MPs need to worry about wider consequences on individuals, and organisations such as trade unions only really worry about their members. The inflation level of intervention, and wider aims make the Bank of England role a particularly difficult one to evaluate.

This all leads to the situation we now find ourself in as a country. Regardless of what we think of the Bank of England, most readers of this blog I would imagine, will understand the need for *some* organisations to be independent of government to make decisions that help shape longer term factors that are of great importance, and to not be at the mercy or whim of relatively transient governments and timelines. Inflation and other top level economy matters clearly fall in this area of interest.

It is easy to be critical of the BoE, and I have done as much above, but what is the alternative? A key misunderstanding of policy work is the belief it can be done without some losers – policy can only ever expect to set the wider framework. The translation of ‘good’ policy into actions is where many a reasonable policy has failed or ground to a halt due to the impact on individuals or groups e.g. migration policies may be divisive, but it is not an unreasonable policy position to try to influence migration (in whatever direction). The ways of going about that however have consequences and can’t be ignored. The bank of England seems to be in a fairly unique position that their entire function does not really require them to worry about the consequences of their policy decisions at below the country/economy level and those lower levels simply become the governments problem. As much as I believe the Bank of England should be independent and are trying to deliver on their remit, I can see the reason that some parts of government might not be happy with the arrangements as they exist today.

I lived through a similar (worse probably as I’d borrowed a much greater income multiple) experience to the young ermine in the late ’80s and early 90s. I couldn’t understand at the time (and still don’t) why the government didn’t raise taxes rather than interest rates to tackle inflation (the BoE wasn’t independent then). The increased tax revenue could at least have been used to good effect.

Well, with an annual salary of over £575,000, Andrew Bailey’s job hardly looks like the worst job in the world. He sits in that segment of life that is usually described as highly privilaged, and even if it all goes Pete Tong for him in that job, he’ll hardly be struggling financially.

Anyway, He, the B of E, and the government are now singing from the same hymn sheet. More austerity. Same old, same old, failed thinking.

@Gizzard #28

> why the government didn’t raise taxes rather than interest rates to tackle inflation

It is a long time ago but I think the UK was in the exchange rate mechanism then and the interest rate hikes were made to make the pound more attractive to foreign investors, i.e. trying to to support the firefighting purchases done by the Bank of England. They needed response times of hours, not months.

Although TI frequently refers to this high interest rate as having been present for only a short while, days perhaps, my recollection is that this persisted in mortgage rates for months – in those days they were not generally a sequence of fixes and were revaluated only twice in the year. But it was a long time ago. It is possible that the high rates impaired my personal finaces and it was this overhang I remember, I was young and foolish then…

@ermine, it sounds as though you are letting your own bad experience of owning your own home cloud your judgement. For the vast majority of people buying their own home has and will likely be an excellent investment. We bought a house in London SW4 in 1985 and sold it in 1992, losing about 5% nominal (much more in real terms) and that was after a lot of improvements. But if we had stayed put that house would now be worth about 10 times the amount we sold it for. If we still had a mortgage, we would be paying substantially less now than then and all the time saving on ever increasing rent.

I do remember a lot of people suffering during that period and some in dire situations, such as splitting with partners but unable to sell/move out due to negative equity, but sticking at it, saving hard and paying down the mortgage would have come good for most people.

Sure there are risks with big financial commitments, but home ownership is a risk where the odds are heavily stacked in the investors favour.

@TI, if you look that extreme case up on Rightmove you will find that the property was bought leasehold, but sold freehold. It seems highly likely to me that the original property had a very short lease, not uncommon for central London, and the owners injected millions in buying the freehold.

The problem with all economic forecasts is that they can only ever take into account what they know. It is likely that what unfolds will be dominated by what is not known at the time of the forecast.

Good forecasters are merely lucky forecasters.

@Naeclue #31

> it sounds as though you are letting your own bad experience of owning your own home cloud your judgement. For the vast majority of people buying their own home has and will likely be an excellent investment.

Did you miss where I said

It’s Russian Roulette, but probably with 50 chambers, and a slightly less devastating tail risk. Sure, 49 others will say it’s great. It’s made worse by the fact that success in noisy whereas failure is generally silent. That’s why we have property is my pension, the Telegraph fulminating about how beastly the Government is to hard-working BTL landlords. I agree entirely, For the vast majority of people buying their own home has and will likely be an excellent investment.. For those that aren’t in that vast majority, it will be financially devastating.

@ermine, ok so what are you proposing? Go in with your eyes wide open to the risk? Mitigate the risk as far as you can by paying full attention to lease clauses, surveys, being realistic about your ability to pay in the case of rate rises, falls in prices, etc? Or just don’t buy because the tail risk is not worth it?