Okay, so you’re late in your career. Perhaps ten to 15 years from retirement.

Your pension pot is sizeable. But you’ve still got a way to go before it can support your ideal retirement lifestyle.

The problem? A major stock market crash would set you back years – creating a hole that can’t easily be repaired by new contributions.

This is dubbed the Retirement Red Zone by researcher Michael Kitces. Here sequence of returns risk looms largest over your road to freedom.

Once you’re in the red zone, your wealth outcome depends more on future returns than on future pension contributions.

A run of good equity returns in the next decade or so can speed you to the retirement finish line. Think of it as like a Boost Pad in Mario Kart.

Unfortunately, bad returns could lurk around the corner like banana peels. Hit one and you could spin off your retirement track:

- A sequence of poor returns will postpone your FU day 1 if you’re intent on hitting your original target number.

- If your retirement date is fixed, a large reversal means settling for a smaller pension than you’d planned.

Shifting your asset allocation from equities to more defensive assets is the tried-and-trusted way to reduce such risks.

The quandary is that the historically average investor scored the highest average returns by sticking with 100% stocks. So derisking is likely to reduce your long-term returns.

N of one

The key point to grasp: you’re not an average.

I don’t mean you’re a beautiful snowflake.

I mean you get one shot at this.

You’ll only ever travel along one foggy route to retirement. And we can’t know in advance whether it’s paved with Boost Pads or banana peels.

So how long can you stay pedal-to-the-metal in a high-risk, high-reward portfolio?

When should you ease off the equity gas, such that you can still reach your destination on time while lowering the chance of skidding off on the final bend?

Derisking your portfolio pre-retirement series Read part one of the series for the scene-setting explainer. It covers the central dilemma of derisking and runs through the risk modifiers that could influence your strategy. Note, this series assumes you intend to live off your portfolio. Some people have other options and can afford to ignore the Retirement Red Zone. If that’s you, and you’re willing to bear the risk of 100% equities, then best of luck!

Give yourself time to recover

One way to think about when you should derisk is to consider how long it takes to recover from a bear market. These are the stock market carve-ups most likely to derail your plans.

The average bear market recovery time for a 100% world equities portfolio is six years and six months. That’s an inflation-adjusted figure, which is what really matters since your cost of living will rise over time, too.

Recovery here means you just about get back to where you were before the crash. You’ve still got to reach your actual target retirement number.

Scare bears

The average bear market recovery for world market equities masks a range of fates:

- The shortest recovery time was one year and 11 months.

- The longest was 13 years and nine months.

And even that lengthiest global market bear was outdone by a terrible 16-year recovery slog found specifically in the US stock market record. This dream-crusher was formed from two bears that arrived in quick succession. Merge them into a single event and equities were underwater (aside from two months of real-terms recovery time) from December 1968 to January 1985. 2

As this chilling example demonstrates, you really can be battered by multiple bears in your final years of accumulation.

On the other hand, you might avoid a bear market completely.

Moreover, the timing matters.

Derisk early or late?

Imagine your portfolio as a civilisation that’s learned there’s such a thing as killer asteroids.

You know these cosmic collisions can vary from extinction-level events to flattening a bunch of trees in Siberia.

Sadly, your telescopes, astronomers, and computers can’t predict when the next Big One will be. They only know it will definitely happen at some point.

As the President of Earth, you order up a planetary defence system.

If you move enough money into the project then you could have a pretty good ‘iron dome’ operating in short order. Maybe even a golden dome!

But that’s expensive and it interferes with the other priorities of your United Earth global government. Such as maxing out growth!

So you decide to hedge your bets, mandating a gradual deployment of resources into anti-asteroid BFGs.

After all, the Big One might never happen.

You are indeed a wise and AMAZING PRESIDENT!!!!!!!!

Even if you do say so yourself.

An inconvenient truth

But wait! Your chief-of-staff cuts the power to your tanning bed to point out a flaw in the strategy.

What if a massive space rock smashes the planet in the next few years? Maybe even next year? While defences are still flimsy?

Yes, in a decade’s time you’ll have low Earth orbit bristling with nukes.

But until then the population will have to make do with hard hats and huddling in tube stations if the joint gets wrecked.

“Insolent cretin!” you sagely respond. “The longer we delay dealing with the risk, the greater our future wealth.”

“The people will rejoice and be happy! Assuming we’re not all flattened in the meantime.”

“It’s more costly to defend a smaller civilisation and there’s less point in doing so. I can’t justify that to the voters / demons in my brain.”

“Hence I’ll strike a balance between jam today and jam tomorrow. Don’t worry. It’s the same principle with climate change and look how well we’re doing with that.”

You pop your shades back on, fire your minion, and dictate a decree ordering a shift of 2% of planetary wealth into defences for the next decade.

Repair job

OK, let’s see if there’s a way to rev up those bear market recovery schleps.

In actuality, six years and six months average recovery time is probably too pessimistic. That’s because investing through the downturn will hasten the recovery, depending on the size of your portfolio contributions.

The table below shows this effect on the last two bear markets, both of which were monsters:

| Bear market | Monthly contributions (% of portfolio size) | Recovery time |

| Dotcom Bust | 0% | 13 years, 9 months |

| 0.125% | 10 years, 4 months | |

| 0.25% | 5 years, 6 months | |

| 0.5% | 4 years, 11 months | |

| Global Financial Crisis (GFC) | 0% | 5 years, 3 months |

| 0.125% | 3 years, 2 months | |

| 0.25% | 2 years, 5 months | |

| 0.5% | 2 years, 2 months |

Data from MSCI. November 2025. Monthly contributions are a fixed percentage of the portfolio’s value at the market peak before the bear market. Recovery times are inflation-adjusted.

As you can see, ongoing contributions can drastically shorten bear market recovery time versus not investing.

Obviously the larger your contributions, the more equities you’re buying at cheap prices. Hence the quicker your portfolio is made whole.

Still, the examples show that there’s a diminishing return to increasing your contributions.

The 0.5% investor only gains three months on the 0.25% investor during the GFC. Even though they contribute double the amount into their pension pot.

Incidentally, the 0.125% investor took over a decade to make good their losses after the Dotcom Bust. That’s because they were still underwater when the Financial Crisis struck.

The larger contributors recovered from the Dotcom Bust only to run slap bang into the GFC within a couple of years anyway.

Easier said than done

Intriguingly optimistic though these results are, I need to run a more comprehensive review of the difference contributions make.

Still, at first blush, it’s fair to assume you can knock years off the longest bears so long as you:

- Invest a reasonable fraction of your portfolio on a monthly basis

- Don’t lose your job during an economic slump

- Don’t sit on the sidelines waiting for evidence the crisis is over

You can still find GFC-era comments on Monevator from people who couldn’t bring themselves to invest at the time.

It was the wrong move, albeit understandable. Nobody knew how bad the losses would be. And there was no evidence the market had bottomed out in February 2009. 3 The aftershocks continued for years.

By the time confidence was restored for some, the opportunity to buy cheap stocks had passed. And while the GFC was bad, the losses were far from the worst even in living memory.

The takeaway: it’s no small thing to decide you can run a bigger risk on the grounds you’ll carry on investing regardless.

What do target-date retirement funds do?

Target-date retirement funds are offered by many of the world’s major fund managers. They put derisking on auto-pilot for mass-market investors.

We can think of target-date funds as:

- Aimed at relatively conservative investors on a standard path to retirement

- Middle-of-the road products engineered to avoid lawsuits and hence defensible in terms of approach

Most target-date funds follow a standard glide path – lowering equity risk for their investors as they head towards retirement.

Approaches vary around the mean but Vanguard’s Target Date Retirement Fund is as good an example as any.

This graphic illustrates Vanguard’s derisking method:

- 25 years before retirement (BR) The move from equities to high-grade government bonds begins. The shift occurs at a rate of around 1.33% per year

- Ten years BR The portfolio is around 70% equities. The glide path now steepens: selling 2% in equities per year and buying bonds with the proceeds

- Five years BR The fund now holds 60% equities with the rest in bonds

- Zero years BR The newly-minted retiree skips into the sunset with a 50/50 equities/bonds portfolio

Vanguard’s fund then continues to derisk for another seven years in an attempt to suppress sequence of returns risk in the early years of retirement.

If you want a set-and-forget strategy then the target-date approach ticks the box. It reduces sequence of returns risk when it’s most concentrated in the Retirement Red Zone.

Stay on target?

Target-date funds typically begin de-escalating risk early on. They implicitly acknowledge that bear markets can last a very long time in extreme cases.

But a chunky equity allocation is maintained into the final decade – complying with the President of Earth’s executive order to balance jam today with jam tomorrow.

Later in the series we’ll present the case for alternative strategies.

But the target-date approach works perfectly well and makes for a good baseline.

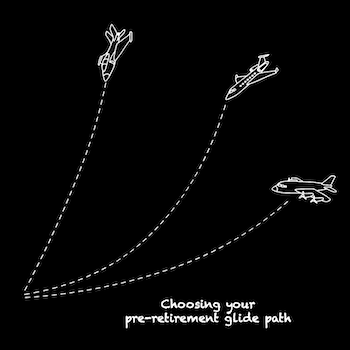

Glide paths for early retirees and FIRE-ees

Early retirees and investors gunning for FIRE can potentially afford to take more risk than traditional retirees. That’s because in theory they’re more flexible about their retirement date.

The best effort I’ve seen to put numbers on this is Early Retirement Now’s pre-retirement glide path article.

ERN tested ten and five-year derisking windows and segmented the investor population into four risk tolerances:

- The criminally insane (I’m joking. But not much. See U=Mean on ERN’s charts.)

- The highly risk-tolerant (Pirates, probably. Or my co-blogger The Investor in his pomp. See y=2.)

- Traditional retirees (Relatively conservative. Someone who is happy with a target-date retirement fund. y=3.5.)

- My gran. (But not my Irish gran. She was a whiskey smuggler.) U=Min.

ERN carved up the results still further depending on monthly contributions and, heroically, his chosen stock market simulation method.

I recommend paying special attention to the cyan line in his graphs. It plots equity reductions during high CAPE ratio periods – that is, when the stock market looked expensive. Like now.

Finally, Initial Net Worth = 100 means the portfolio is worth 100 times monthly contributions.

(I suspect that making contributions on that scale is a tall order for most investors ten years from retirement, but it’d be great to hear what your experience is in the comments.)

Here’s Big ERN’s key ten-year glide path chart, graffitied with my explanatory annotations:

Source: Early Retirement Now

ERN’s numbers suggest that even risk-tolerant investors should consider being no more than 60% in equities when ten years from retirement.

That’s judging by past US equity returns associated with high CAPE ratios (the cyan line).

Intriguingly, ERN’s chart also shows that risk-tolerant investors would be justified in sticking with a 100% equities allocation when stock market valuations were more normal (dark blue line).

However, the S&P 500 currently looks extremely pricey according to CAPE readings. That increases risk.

ERN also produced a chart for more cautious investors who want to retire on time:

Again, the cyan line is the one that best corresponds to the current investing environment.

ERN’s results concur with mainstream target-date thinking: get down to 60% equities ten years out, then glide down further by retirement.

As it happens, ERN’s middle-of-the-road investor ends up with 40% equities in the end.

Your mileage may vary

I recommend reading the entire article in full. Bear in mind that Big ERN writes from the perspective of a US-based investor hoping to achieve FIRE.

It’s fair to say he’s also a highly sophisticated investor with a pretty strong stomach for risk.

I mention this because derisking is such a complex and consequential topic that it’s important to weight any research in light of its applicability to your personal situation.

From a timeline perspective, ERN’s research also comes with an important limitation: he didn’t consider derisking glide paths longer than ten years.

Thus his findings don’t conflict with the standard financial industry glide paths that begin derisking earlier.

Risk modifiers

There isn’t an optimal time to start derisking your portfolio because hitting your retirement target number or fixed date depends on many uncertainties.

This means I can only present you with a range of factors to consider or discard at will.

Just to add to the complexity, here’s a table of risk modifiers that could further influence your decision:

| Derisk earlier / more aggressively | Derisk later / less aggressively |

| Your retirement date is effectively fixed by health, job type, burnout, and so on. | You can work longer or part-time if markets are ugly. |

| You have no meaningful safety net outside the portfolio. | You have other sources of retirement income. |

| Your plan doesn’t allow for much discretionary spending. | You’re willing to cut consumption. |

| Your pension contributions are low relative to your portfolio. | Your savings rate is very high. |

| You can’t stand the idea of large portfolio losses. | You’ll aggressively invest in the teeth of a massive bear market. |

| Expected equity returns are low. | Expected equity returns are normal to high. |

Alright, that’s plenty to digest on when to derisk pre-retirement. Next time we’ll look at what to derisk into. There’s more to life than stocks and bonds.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

Thanks so much for a thoughtful article. I’m currently pondering this exact scenario. Likely a couple of years from FI.

It will be 10-12 years (on current rules!) before I can get at my DC pensions so keeping invested in equities there seems to make sense as it’s all locked up anyway.

The conundrum is what to do with my non pension assets (world equities, some cash, a little gold), due to the stock market charge I’ve sleptwalked into a rather high equity %!

This article is so good, its astonishing you give it away for free. Thank you. I need to reflect on it and digest it further. For now, I’ll just say: doesn’t Kitces advocate (with a small ‘a’) building a ‘bond tent’ (say for 3 – 5 years’ spending) but otherwise being 100% equity? Would be interested to know of any critique of that, particularly in the high CAPE environment we currently inhabit. I can see the logic of (what I understand to be) the Kitces’ view, but I also feel the slight emotional discomfort of following it…

As I was treading this path many years ago now I rather reassuringly discovered some work on long term asset allocations in the Bogleheads forums that gave some pointers to a way ahead on de risking which includes pre retirement scenarios

70/30 right through to 30/70 asset allocations gave satisfactory long term results to investors

US figures admittedly for (1926-2015)

Average annual returns 70/30=9.6% Average annual returns 30/70 =7.3%.

This gives the investor lots of scope to choose his personal level of volatility and risk strategies and still come out a winner

Personally at retirement I was on 30/70 -am now 35/65 and have had a satisfactory retirement-so far! (Aged 79-23 years rtd)

xxd09

PS the link to receiving follow ups to posts on threads seems to still only work intermittently for me sadly

@Andy: You write:

Thanks and agreed! 🙂 Of course everyone should sign-up to keep all TA’s brilliant articles coming, both free and members-only.

His eccentric hobbies (chasing cows, wearing fat suits in winter) are cheap but they are not free. 😉

“equities were underwater (aside from two months of real-terms recovery time) from December 1968 to January 1985”: that’s terrifying, we’re taking about endurance stretching from just before the era of Woodstock right through to the year of Live Aid. No wonder there was that ‘death of equities’ headline in 1979.

This is a very important and complex issue. Monevator are doing a great job in this mini series. If this topic interests you I would highly recommend listening to the eccentric (but in my opinion brilliant) Frank Vasquez on risk parity radio https://www.riskparityradio.com/

@The Investor – I think I’m already a Maven member. But please do drop me an email if that’s lapsed and I’ll remedy 🙂

Thanks for the reminder that the Vanguard target date funds contain short-term linkers. Could be a convenient way to hold x% in what appears to be a rolling linker ladder (the latest annual report shows that the 2015 and 2020 funds hold 2026, 2027, 2028 and 2029 linkers).

What do investors do that ran with a 100% equity portfolio and hit their fire number now? Simply sell off 40% of equity, take the hit on capital gains tax and use the cash to buy whatever your target asset allocation looks like?

The inflation-adjusted recovery time figures make for sobering reading. And a just retired or FIREd person is going to be at the 0% per month contributions end of the scale, so minimal opportunity to shorten. I guess sitting on an enormous pile of bonds will help as ammunition for rebalancing into equities as their value shrinks, although rebalancing frequency in a downturn is another decision that needs making.

So many excellent articles – I can’t keep up with the reading!

That section on how “ongoing contributions can drastically shorten bear market recovery time” was a real eye opener. I’d thought about that before, but never seen it laid out with the numbers like that. It’s also a great reminder for those in accumulation, especially early on, to Just Keep Buying.

I’m well into the red zone – just quickly doing one more year. Again. Although I did take note of what @ermine and others recently said about overdoing it – a sobering reminder.

@Baron #10 – that’ll soon be me at the “0% per month contributions” end of the scale. And no, I’m definitely not doing another “one more year” after this one, even if markets turn ugly, as TA puts it.

On rebalancing in a downturn: until recently I ran a 10×10 portfolio (10% in each of 10 asset classes) and mechanically rebalanced whenever any asset class moved by 10%.

So with say a £1m portfolio I’d rebalance when any asset class hit £90k or £110k. It’s a narrow band, but it’s worked for me psychologically, and it saw me through the COVID slump – although I’ll admit I felt a bit queasy buying equities on the way down, especially on 23 March 2020.

Looking forward to more comments and the next article in the series, TA. In the meantime I’ll read ERN’s piece.

Thanks as ever for thought provoking post. Very topical for me as thinking of firing next year.

I’d not explicitly considered the if savings rate high relative to pot size -> afford higher equity allocation , but that’s essentially where I was up to 2020. But great returns have seen the pot size grow relative to contributions, so started the Glidepath out of equities not long after the 2020 recovery.

My appetite for one more year is rapidly waning. And along with US valuations this has hastened the reduction in equity exposure since. Now sitting at around 55% with the rest predominantly in linker ladder and cash. Which seems to be in the right ballpark for a year or so beforehand according to ERN at least!

@Tom #9 for those in the UK I’d hope most would max out SIPP and ISA allowances before investing in general accounts. And so could switch out of equities inside the tax/wrappers instead?

A scenario I could see where this isn’t necessarily the case would be an entrepreneur with their wealth invested in the equity of their own business, effectively entirely in the GA. I think this is a pretty unfortunate scenario (the CGT allowances having shrunk massively in recent years). These CGT thresholds do not feel like they fuel growth – but that’s straying into budget discussions.

Imo the income yield risk is just as important as the capital risk but often overlooked. FTSE buybacks dropped during Covid, but dividends largely held – so you can get a pullback and maintain a good cash yield on stocks (but it depends on the type of pullback and on whether an index pays good yields).

Conversely you could get terrible yields if you pivot to cash, and cash yields drop off five years from now. That can be more problematic than a pullback long-term.

Long term bonds have both risks and benefits and maybe aren’t a bad call now with yields reasonably high (although 15% is top of the range), but if yields were 1% you’d be daft to go all in on long term bonds to avoid stock pullbacks. You’d just exchange a chance of death with certain death.

So I’d always have some of each and rebalance based upon both income risk and capital risk (ie considering risk of interest rate movements up & down), adjusted for circumstances.

For those of us even more risk averse or who require more certainty in retirement income, there are two further potential solutions – one of which is mentioned by @Prospector (#11)

1) Delayed Linker ladder. A 30 year linker ladder set to start in 10 years time (so perhaps suitable for someone aged 55yo) currently has a withdrawal rate of 5.2%. In other words, an inflation linked income of £10k per year would currently require an investment of just over £190k. This could be built gradually (with interest rate risks) or all in one go with further contributions then directed to the risk portfolio.

2) A single life RPI annuity taken at 65yo currently has a payout rate of 5.2% (with real yields of about 1% over a 10 year delay, this gives an effective payout rate of 5.7%). This income can be approximately* locked in by duration matching using two (or more) linker funds or individual linkers. It is unfortunate that, AFAIK, single premium deferred annuities are not currently available to retail customers in the UK (i.e., equivalent to the DIA or QLAC in the US).

* modelling I’ve done with nominal annuities indicates that historically (1916 to now) the income could have been locked in within about 5% of the target value in 75% of cases even with no duration matching (although in the worst cases the tracking error was over 20% – in other words a target income of £10k could have been lower than £8k). I’ve not yet completed the historical modelling with duration matching so cannot offer any results.

Great post as usual. We are “nearly” retired – just working a couple of days a week now. Pressing the button September next year when we will be age 57/56. I started de-risking around 3-4 years ago and now sit at 40% risk off /60% risk on. Increased the risk off quite a lot over the last 6 months – yes valuations have me concerned.

In fact probably more like 35%/65% when taking into account some cash I hold in reserve to cover a year or two of spending.

Context – very small DB, otherwise everything in retirement is coming from investments. To hit our income needs we are probably looking at a SWR of around 3%. We really do not want to go back to work once we hit the button. Traditionally 100% equities.

Couple of points and would be interested if you have a view?

I have read various pieces that seem to report the difference between say 45%/55% through to 55%/45% seems to be minor. So just being “in the range” seems to be ok (McClung Living off your money p184 for example, shows these all have a SWR of 4.3% for example). Sure ERN has something on his website about this, but have not come across it. Pfau backs this up (How much can I spend in retirement p87). 75% /50%/25% stocks all give a 100% success rate at 3% SWR. So being at the “more risk off” end of the allocation does not seem detrimental.

I am considering a reverse glide path, back to 60% / 40% over the next 5 years or so. Something ERN does seem to consider a good idea once you are over the early years of retirement. But I need to thing about this a bit more – i.e. do I need to and why – legacy?

Thanks for this thought provoking article TA. I’m 6 years into retirement now, however if I was 10 to 15 years from my planned retirement date I would still continue purchasing my 100% global index fund of choice on a monthly basis. And would ensure any life styling was switched off if it was the default strategy in my DC savings scheme. 10 to 15 years out I would be praying for a market crash any time soon as my contributions would be purchasing cheaper units in the index fund. Also, like most folks, I found I could increase my pension contributions in the latter years of my career, when financial commitments and mortgage was smaller etc. Back in the day I was maxing out the DC pension £40k annually, taking my employers 10% reference salary contribution and salary sacrificing the most I could. I think the biggest risk is a market crash plus or minus 3 to 5 years from planned retirement date. Maybe flip to your post retirement investment strategy 3 to 5 years before retirement date? But I would say de-risking pension investments 10 to 15 years before is far too early.

@TA:

Interesting post – and I thank you for all the work that has gone into it.

Re: “Intriguingly optimistic though these results are, I need to run a more comprehensive review of the difference contributions make.”

Agree entirely – IMO the results [in the Table] are not intuitive. To my eyes at least, they imply a sweet spot; albeit one that is dependent on the unknown (at the time) characteristics of the actual bear recovery. Tricky!!

A few days back you asked about a hedging strategy IIRC for a downstream purchase of an Annuity. I mentioned then that perhaps Alan S might have some suggestions. At a first glance, option 1 in his comment above (#14) might be a good place to start.

For my DIY deaccumultion strategy I created a spreadsheet with time and income. Blocked out the amount and when the state pensions would arrive. Then infilled the rest with inflation linked bond ladders using ISAs and SIPPs to try and reduce tax take for a length of 29yrs. What was left I’ve put into value tilted equity.

The greatest insight I got was that my risk appetite had dropped off the cliff. That really surprised me.

I know I won’t meet the grim reaper with bulging pockets in my shroud, but it hopefully isn’t a begging bowl either.

These are super interesting articles, and I am also re-reading the no cat food series as I am thinking of ditching the current job end of FY 2027. One thing that did cross my mind is the sheer complexity of it. It’s a huge step up from the slow and steady portfolio stuff. I wonder whether it’s possible to apply some sort of Pareto/Occam’s type approach where you have a 20% solution that gives you 80% of the results? I mean solution in terms of complexity of implementation. Results being similar chance of success, i.e. not going broke. A part of me thinks that it should be possible to retire earlier than state pension age without having to read mclung (I do actually own a copy) or being capable of implementing a bond ladder. Just a thought, don’t really know if the suggestion is feasible? As Ian points out above, how much of the detail that doesn’t necessarily move the dial that much could just be cut altogether from the thought process?

@Rhino – I completely agree. Maybe it’s only possible because I have a DB pension as part of my mix, but I’m tempted to make my DC pot as simple as my preferred allocation across cash and a global equity tracker.

@Andy Dufresne – Cheers! I really appreciate it.

Kitces bond tent turns out to be pretty conservative:

– 10yrs before retirement: 40% bonds

– 5yrs BR: 60% bonds

– Retirement: 70% bonds

– Retirement +5yrs: 60% bonds

– Retirement +10yrs: 50% bonds,

– Retirement +15 yrs: 40% bonds

I think this next quote is key:

“Notably, there’s still far more research to be done to optimize the exact shape and the slope of the V-shaped equity glidepath and the bond tent. It’s not entirely clear how quickly during the pre-retirement red zone the bond allocation should build (i.e., the pre-retirement glidepath), nor how quickly it should be liquidated in the early retirement years.

It may be that the equity exposure should be shaped more like the letter U than a V, such that the bond tent would have a wider roof – an extended period of time where greater bond allocations are held as a reserve. And the exact height of the bond tent – how high the bond allocation should reach – may be further optimized as well, especially given today’s low-yield environment (where bonds are less appealing to hold relative to historical standards, but still better than holding equities with even greater volatility and sequence risk).

And of course, there are other fixed income alternatives besides traditional bonds that might be considered as “volatility dampeners” and “diversifiers” as well.”

https://www.kitces.com/blog/managing-portfolio-size-effect-with-bond-tent-in-retirement-red-zone/

Essentially, ERN’s work is an update on the bond tent idea.

According to his results, cautious investors are 60% defensive at retirement and the risk tolerant are more like 40%.

ERN did some work on the rising glidepath too – the inverted V of the bond tent. IIRC it helped sometimes but not that much.

I’d add that the defensive allocation requires greater diversification than nominal bonds. More on that next episode.

@tetromino – Yes, I think you’re right about the rolling short-term linker ladder in Vanguard’s Target Date Fund. Thankfully it’s not their long linker fund.

@Tom – Yes, you could boil it down to that. Though you could sell off more or less – it depends on what risks you’re prepared to run. Here’s a list of the stock market crashes you could face:

https://monevator.com/bear-market-recovery/

They come without warning most of the time.

@Baron – The same thought occurred to me: that it’s much worse for someone in decumulation. Even worse than contributions being at 0% because they’re forced sellers if they’re living off their portfolios.

Rebalancing often doesn’t make much difference or can make things worse during a very long bear market i.e. you keep trading into equities but they keep going down.

Finally, I’d add nominal bonds are good during a demand-slump but bad during an inflationary crisis. We need assets that can withstand an inflationary bear market too.

@Prospector – Same. My savings rate was approx 1% relative to pot size. I think that was probably pretty high based on a very quick bit of research.

My guess is that the Monevator Massive skews high relative to the wider UK population.

Personally I think I would have been psychologically devastated if my portfolio had been smashed right at the end by a big bear. I thought it was happening with Covid and I guess I was alright, but that crash was over so quickly.

@Alan S – I think those are two excellent strategies.

@Ian – I think that’s right. Essentially risk-on increases the range of outcomes: anywhere from disaster to dying with huge sums in the bank.

While a more moderate allocation to equities tightens the range. Less chance of disaster, smaller sums left in the bank.

At some point you can go too far i.e. 100% bonds is a terrible idea. But 60% defensives looks basically fine – just smaller odds of punching the lights out.

A rising glidepath is predicated on the idea that equities outperform other assets over time, on average. I’d need to go back and check but my memory is a rising glidepath can help but not that much. Far from necessary.

@DrexL – It’s such a personal decision. 100% equities was too strong a brew for me when I started derisking. I was never less than 60% equities even at the end but in retrospect I rode my luck.

Those bear market recovery times indicate to me that 3 to 5 years is leaving it very late but that’s just how I feel about it. I agree with you that 15 years out seems very long. That said, ERN’s results indicate a 60% equities portfolio with 10 years to go. Presumably his results would show an off-chart glidepath down from 100% to 60%. Start that 5 years earlier and you’re shifting 8% per year from equities to bonds.

As an aside, I have a friend who wants to be done in six years. Her pot isn’t really big enough yet and it’s a massive dilemma. She needs more growth but I fear for her with valuations at current levels.

@Al Cam – Cheers! And yes, I agree. I need to run the numbers across the full range of bear markets at different rates of contribution and see what that tells us. Think I’ll devote a future post in the series to that. Ran out of time with this one but thought it was worth sharing my initial results.

I was hoping Alan S would come in on the annuity hedging point and he has 🙂

@Sleeping Dogs – “The greatest insight I got was that my risk appetite had dropped off the cliff. That really surprised me.” Yes, that’s what happened to me too. Quite shocking in a way and it effectively forced me to derisk. Nice work with the linker ladders!

@Rhino – That’s a great idea for an article in itself. Clearly many / most people get through retirement without worrying about any of this stuff.

Perhaps they oversave in the first place, or get lucky, or in some cases lead lives of quiet desperation.

The rules of thumb are the Pareto approach, I think? 100 minus your age in bonds etc. That’s OK but gets ripped apart by an inflationary crisis. Target Date Retirement funds fall into this bucket too – though VG’s is protected against inflation to a degree.

Annuities are another – possibly the best – solution. But people hate them and make major mistakes like choosing a level annuity. Also super expensive when yields are low / negative.

DB pensions make life a lot easier. I don’t have one 🙂

I suppose when you strip it back two questions need answering:

– How do I cope if I get unlucky?

– How do I neutralise inflation as one of the ways I could get unlucky?

For scenario planning, I think there’s definitely a case for DM AAA govies.

Downside: they’ll be expensive to hold until the next market correction, whenever that happens, because inflation is sticky.

Upside: part of the inflation comes from asset-price effects — the American crypto nonsense, the Magnificent 7, and other pockets of excess wealth pushing spending in certain sectors. (Yes, energy prices matter too, but the demand for energy is being driven in part by those same overfunded pockets.) Last time we went state-side, the whole place reeked of money sloshing around.

A plausible correction scenario: crypto and tech capital gets trimmed, triggering a demand-side slowdown and lower energy prices. Inflation falls, central banks cut rates, and DM govies benefit from both lower rates and a flight to safety.

But: expensive to hold in the meantime, and who knows when the correction will come — a year, five, ten… or AI takes over the world and solves the problem for us.

Then again, there’s also a case for gold, at least until China stops buying it. And unlike crypto, gold actually does something in the real world.

@Rhino. I hear you on that crusade. I too own Mclung ( even implemented it at one point.) I came to the point it’s either Probability or Safety first (liability matching portfolios etc). I had a set of criteria to try and hit i.e. 57 yes old, wife 8 yrs younger, no interest in finance… At all!

Severely shrunk cojones, want guaranteed income when I’m fit enough to enjoy it, etc. I’ve also got a swivelley suspicious eye on financial repression… Too much Napier / Chancellor perhaps. If that does come down the line, then it’ll be a different investing environment. That Bernstein article from the weekend added to my swivelleyeyedness…

I didn’t find a way that works for me without getting to grips with bond ladders. Tbh the buying bit was easier than I suspect the managing the cashflow will be. (I ended up with about 7 ladders.)

So did I nail the 20:80? Well I think the effort was probably 40/50 and the result will be 50/60 …

PS I’m quite enjoying that 365 yachting chap’s piece on the 07-09 GFC. I’m hanging on in there with the jargon, but getting the gist.

Good luck with the quest and keep on keeping on with your comments over the years… Very witty!

@TA (#21)

“@tetromino – Yes, I think you’re right about the rolling short-term linker ladder in Vanguard’s Target Date Fund. Thankfully it’s not their long linker fund.”

I don’t doubt you but I can’t find anything on the Vanguard UK website that confirms they are a short-term ladder. In the Portfolio Data for the 2025 fund (https://www.vanguardinvestor.co.uk/investments/vanguard-target-retirement-2025-fund-accumulation-shares/portfolio-data), under the Allocation to underlying Vanguard funds heading it merely says ‘United Kingdom inflation-linked gilts’, which suggests that it’s just their usual IL gilt fund (though I acknowledge there’s no “Acc” suffix).

Do you have a link to more detailed info? Thanks.

Re: simplification, many years ago (like c.15 years ago!) @TA explained to me he felt he needed to read literally tens of thousands of words on passive investing and index funds in order to have the confidence to just invest in a handful and let the market do its thing.

In other words, he needed to understand all the complexity to believe in simplicity.

Leaving aside the fact that de-accumulation *just is* more complicated, uncertain, and unforgiving, I think there’s probably also something similar at work here?

i.e. I suspect it’s not a coincidence that two long-time readers who’ve suggested a simplification crusade also own McClung 😉

Not to knock the concept — I’m all for it — but I think it’ll be an additional article with jump-offs back to this one rather than a one-and-done ‘do this just because’ type affair. (Appreciate nobody was suggesting exactly that, just taking extremes to make the point.)

Cheers for the great comments!

@Curlew

Yes, it’s not clear unless you look at the annual report or interim report at the bottom of the ‘overview’ page.

In that, find the fund you’re interested in and they have both a ‘portfolio statement’ and ‘summary of changes’ where you can see the individual gilt holdings: https://fund-docs.vanguard.com/lifestrategy-annual-report.pdf

@Curlew – Yes, go to the pro site – you can generally find more detail there than on the retail investor version.

https://www.vanguard.co.uk/professional/product/fund/target-retirement/9667/target-retirement-2025-fund-accumulation-shares

Download the annual report.

Go to the Target Date fund you’re interested in.

You can see what they’ve traded and what they currently hold.

Funds 2015 – 2025 hold specifically named linkers maturing 2026-29 as @tetronimo mentioned.

They don’t list the Vanguard linker fund.

That lack of a suffix on the retail investor site is key. Intriguingly the same page on the pro site states:

*Allocation to underlying Vanguard funds*

Then doesn’t list a linker allocation at all. Because VG’s target date funds hold individual linkers not the VG long linker product.

@TI – yes, I have trust issues 🙂

Just to add something to your very fair point. My intention was always to run a tight FIRE i.e. I have a little spending flexibility but not a great deal. That’s why I’m interested in McClung’s ideas and optimising decumulation more generally.

If I had tons of wiggle room then I wouldn’t bother.

That tracks back to the less you need the money (or can cut consumption), the more risk you can take.

As an aside, my circa 2019 calculations were based on tax threshold’s continuing to rise with inflation. I knew that was a risky assumption to make but decided to live with it. Unfortunately, that was wrong and a few more rivets have blown out of my decumulation submarine.

That’s OK, I can make it up elsewhere, but no plan survives contact with the enemy etc…

“Annuities … But people hate them”

They do, and when challenged just haver or indulge in ill-tempered spluttering. Very strange.

The most rational argument against them is that they might lead to you being means-tested out of State Retirement Pension but the Accumulator (I think it was) rejected that as entirely implausible.

@dearieme I am thinking of making an allocation to a CPI linked annuity, since I am retiring right now, it doesn’t need to be deferred. Means I don’t need a linkers-ladder which seems to require me to forecast an RPI/CPI breakeven rate.

@TA @tetromino @curlew I’m a Vanguard UK customer, I’ve sent them a secure message on their broker webapp asking what other individual linkers are in the 2025 Target Retirement Fund. Be interested to know how long is the ladder.

@TI – I give in, I have ordered the McClung book.

@dearieme – I rarely reject anything as entirely implausible. Not even the plausibility of me rejecting something as entirely implausible. But I wonder why – in a mean-tested world – annuities would be singled out for special attention as a source of retirement wealth? For my sins, I read some recent stats on pension pot decision-making. IIRC something like 4% were now choosing to convert their pension savings into annuities.

@Baron – Vanguard’s ladder stretches to 2029 currently. tetromino’s list holds true for the 2025 fund.

Re: DIY linker ladder – you don’t need to forecast a breakeven rate. But an annuity seems me to be the better choice – simpler to manage, you don’t have to worry about length of ladder and you potentially benefit from mortality credits.

@TA, Baron

When I made my earlier comment I was looking at the annual report but the interim report is the latest view I can find. For the 2025 fund it shows, as of 30 Sep 2025, that the holdings extend to 2030:

% of fund / linker

1.22% United Kingdom Inflation-Linked Gilt 0.125% 22/03/26

1.79% United Kingdom Inflation-Linked Gilt 1.250% 22/11/27

1.53% United Kingdom Inflation-Linked Gilt 0.125% 10/08/28

1.54% United Kingdom Inflation-Linked Gilt 0.125% 22/03/29

0.98% United Kingdom Inflation-Linked Gilt 4.125% 22/07/30

The 2015 and 2020 funds use the same linkers, just more of them.

@TA, Tetromino, Baron

Thanks for the responses.

The report was an interesting read. Not sure why Vanguard don’t just put a note on the retail investor site that the IL gilts are UK short-term individual gilts held to maturity (or near enough to maturity) i.e. not a fund and not mixed-maturity.

Nice one, tetromino. I was looking at the annual report too. It’s for the financial year ending March 2025. You can see that for FY 2024-25 they only book proceeds for United Kingdom Inflation-Linked Gilt 2.5% 17/07/2024.

I conclude from that, they either let it mature or sold it slightly early if there was any advantage in doing so.

Lots to think about here, thanks @TA.

As I will have other sources of retirement income (DB pension) and I am willing to cut consumption, your table of risk modifier suggests that I can derisk later/less aggressively.

I have started already doing a bit in my own fashion but look forward to your next post in the series on what to derisk to (probably won’t be to anything I have switched to, haha).

As @Baron mentions, once someone has retired, the contributions will be pretty much zero, so no chance to shorten the bear market effects. Sit on a big pile of cash, ready for buying opportunities?

@weenie #35 > I am willing to cut consumption

I think this is a key. TI’s Nov 22 WR had some dude from The Retirement Manifesto talking about retirement being a sprint not a marathon. tl;dr was front load all your spending because a) you will die, and b) go-go, slo-go, no-go years.

The dude’s an extrovert It’s about what he does, not what he becomes. Extroverts have a harder time with retirement, period. It’s fair enough, they make bank when working, every workplace loves an extrovert.

I violated his criterion, working a white collar job for three years living off minimum wage and salary sacrificing the rest into pensions and employee shares. It was rough, three go-go years burned and a rotten experience. I retired, and spent not so much even then, but I appreciated a huge win, because They couldn’t tell Me what to do with my time. And I spent some of it refining inner space, and yes, some of it getting a little bit less bad at the art of investing.

Retirement isn’t necessarily all about the travel and the cruises you do, it can also be about becoming more you. So the key is knowing thyself. If you know you want to spend big then sure, you hafta do what it takes and if that’s OMY so be it. If you have the flexibility to be opportunistic about your elective spend, then that makes a HUGE difference. Life is a lot cheaper in retirement because you have control of your own time. You can take opportunities as they come, you can take longer with travelling or stay longer amortizing the cost of travel over a longer time. You can wait and dry your washing outside on dry days, you can walk or bike to places. You have the privilege of all the time work stole from you

I was fortunate. I am the antithesis of TA, I’m not particulerly passive, and I took a couple of Hail Mary flyers around Covid and once more. But I have been taking the uplift from GFC valuations since the GFC destroyed my job. There’s a bit of the ‘if you want to get there I wouldn’t start from here’ in that todays valuations suck compared to then. Nevertheless, if you can, be prepared to be flexible on your spend in retirement. No consumer spend tasted as good as freedom feels. Being flexible in the early days of low valuations means I am now a decadent git and don’t need to do that. I’ve given some of it away because you cannae take it with you, and you get to see some problems just plain solved for the recipients and it stays fixed, a joy that keeps on giving. Beats climbing Mount Kilimanjaro in my book but each to their own 😉

I do accept fully that this is different for different people and if the focus is on the outer world rather than innerspace then you’re going to need more, and the sprint guy is right in that case. Even in that case if you are prepared to be flexible on your elective spend you gain greater resilience against bear markets, because you’re drawing down less in them.

Flexibility is your friend. There are analytical solutions to this (guyton klinger springs to mind and ERN has something on this). I spent far too much of my early post-retirement overthinking stuff, I never bothered with that as time passed. You know if you’re worse off than last year, in that case ease back. William Bernstein was right, he pumped out a paper full of mentation about the efficient frontier but in the end 50:50 equities bonds was good enough for him. There’s so much random noise in a retirement the error bars are massive. And remember Einstein’s

Bloody Hell, Einstein must have been a tedious bugger to have a beer with.

@ermine – you are the poster child for early retirement. It fits you like a glove.

Broadly agree that RE probably better suited to introverts than extroverts. But on the go-go, slo-go, no-go, that is very much definitely a thing (I see supporting evidence everywhere I look) therefore it needs careful consideration. But I don’t think it’s an introvert/extrovert issue. It’s just physical/mental decline making your world ever smaller.

Thanks, as always, for your hard work.

Looking forward to your next article on defensive assets. I am uncomfortable plunging further into UKbonds, even linkers.

One point I can make is that after 6 years in retirement a big constraint on sipp drawdown is avoiding 40% tax.

Nice problem to have perhaps but a problem anyway ( especially now that the iht merits have been trashed).

My memory stirs. There is an academic literature about the strange matter of people who would, in all probability, gain by buying an annuity rejecting the idea with a hissy fit of irrationality and spluttering indignation.

That literature refers to the phenomenon as The Annuity Puzzle.

This maybe gives some reasons re: annuities and why not:

https://popstudies.stanford.edu/news/solving-annuity-puzzle

Seems many, like me, don’t fancy their chances of getting their money back and often have to hand over a large wodge to get a “little pocket money” in return particularly if want index linked (and maybe also payable on death to spouse for a period etc.) The insurance companies do do the maths and it works out in their favour otherwise they wouldn’t be in this business – so on average most people aren’t going to gain from this – they’ll be losers and Ins co. the winners. With my luck anyhow I’d likely peg it the day after I’d bought one.

Also seem expensive unless you leave till later age but what use is it if you get to 75 and find you have plenty in your pot anyway. Depends on health and genes/luck whether it will be worth it.

Also to me the state pension is my “annuity” and some would rather have money they can dip into exactly when they want rather than just a monthly payout that maybe lost on death and otherwise could have been an inheritance.

With current S.P. due to fill your annual income tax allowance, any extra annuity means more tax whereas you could possibly arrange withdrawals more tax efficiently if you don’t need the money now and tax allowances (income tax/CGT) are more favourable in future.

Also in DC/investments your pot is hopefully still growing and making you more for the future – not so an annuity. But you pays your money …………….etc.

@AS I think the situation with annuities in USA is quite different to the UK so not sure how applicable the Stanford study is.

The main advantage to me is it provides insurance against longevity risk, which is the hardest thing for me to mitigate myself since I am in a pool of 1.

Whereas the insurance companies have an enormous pool with a distribution of mortalities, so they can offer a product I can’t emulate myself.

Seeing my aim is Die With Zero, the alternative is to end up with a lot of unspent money at the end. I guess the local cats and dogs home will be happy.

I disagree that they are expensive, on the contrary right now the rates on offer for a single CPI linked lifetime annuity seem excellent.

@Ian (#15)

You could consider swapping some of the 60% fixed income into an annuity – currently a joint life, 100% beneficiary, RPI linked annuity pays 3.5% at 55yo and 3.9% at 60yo (so 57/56 will pay somewhere between these two).

The reason SWRs for the US are fairly flat with asset allocation is that they are not all for the same historical retirement (e.g., the value at 100% stocks is for a retirement starting in 1929, whereas for lower equity allocations, the worst case start years are either around the mid-1960s or around 1910. For other countries, the curve is not so flat (e.g., see Figure 2 in Pfau, “An International Perspective

on Safe Withdrawal Rates: The Demise of the 4 Percent Rule?”)

I also note that a planning horizon of 40 years (so lower SWRs) might be more appropriate for retiring in your 50s (see below).

@AS (#41) (and others discussing the annuity puzzle)

At its most reductive, an RPI annuity can be thought of as a ladder of index linked gilts the payout rate for which is increased by mortality and decreased by fees. In general the former outweighs the latter. Whether it is expensive can be directly considered by comparison with some alternatives.

At 60yo a 40 year (i.e. taking the retiree to 100yo) SWR for a 60/40 portfolio has paid out 3.7% (US retiree, using bogleheads simba spreadsheet for returns and inflation) and 2.5% for a UK retiree (macrohistory.net for returns). An international equity portfolio for the UK retiree (half the equities in UK and half in the US) had an SWR of a shade under 3.0% (the exact amount depends on what duration bonds you use). However, there is no guarantee that future markets will sustain 3.0% withdrawals for 40 years.

Currently, a 40 year inflation linked gilt ladder is paying out about 3.5%.

A single life RPI annuity at 60yo has a payout rate of 4.6% (a guarantee period of 20 years will reduce this by, IIRC – I don’t have the figures to hand – about 50bp).

A joint life (100% beneficiary) at 60yo has a payout rate of 3.9% (a guarantee period of 20 years reduces this by about 10 bp).

I agree that the SP forms a useful floor of income and that for many retirees the addition of further guaranteed income will be unnecessary. However, from the simplicity point of view, an annuity has a lot to commend it. A ladder is moderately complex to set up, but fairly simple to use except that the income can be ‘lumpy’ (as a look at the cash flow tab on lategenxer’s excellent ladder tool demonstrates) which requires some ongoing management. Withdrawals from a portfolio can be as simple (natural yield or a percentage of portfolio approach – i.e., variable withdrawals) or complex (Guyton Klinger or McClung’s various methods) as you like with the constant inflation adjusted withdrawal (i.e., SWR) strategy falling somewhere between the extremes.

Most annuities in the UK are protected by the FSCS and the insurance industry is currently much better regulated than it is in the US.

I would also suggest that these tools (portfolio, ladder, and annuity) can be combined to tailor both income and legacy requirements to suit.

@TA (#21)

I do have some preliminary results for locking in the income for a delayed annuity (a 5 year delay) for parallel shifts and non-parallel tilts in the yield curve. Duration matching works quite well for shifts (e.g., the tracking error is about 1% for a parallel shift in yield of 2pp and 4% for a 4pp shift – it is not linear and depends on initial conditions) but is worse for tilts particularly going to inverted curves or when there are strong changes in the gradient of non-inverted curves (e.g., going from a flat yield curve to an inverted one with a gradient of 0.01pp/year led to a tracking error of over 7%). So, duration matching is not a perfect solution and, in order to minimise tracking error, will require monitoring for ‘duration drift’ at monthly or possibly quarterly intervals.

@Alan S – Thank you for the heads up. Will be interested to read your paper once you release it into the wild 🙂

While duration matching is not a perfect solution, are there – in your view – any better ones for a DIY investor who plans to annuitise in the future and wishes to hedge interest rate risk?

I’m kind of with Part Time Analyst “if yields were 1% you’d be daft to go all in on long term bonds to avoid stock pullbacks”

For me, it’s been a case of if yield = 0.5% ignore derisking rules, if yield = 5% embrace derisking rules*.

I’ve been embracing an increase in gilt allocation very late and close to my intended FIRE date for this reason, only building up over the last 2-3 years really, from a standing start and based on a career-high contribution rate that has been supercharged by no longer having a mortgage. This has meant I haven’t had to sell equities to rebalance.

I’ve never really got anywhere even close to maxing out pension annual allowances until fairly recently.

As stated I guess TA will explain more about what to derisk into in the next article, cash, short dated linkers etc. so just because intermediate and longer gilt yields were on the floor wouldn’t have been an excuse not to de-risk in some way.

* – Of course gilt yields could climb to 6%+ if the G7 debt crisis predicted by Gerard Lyons according to The Telegraph today comes to pass. This is why I like buying individual gilts and holding to maturity, perhaps as a ladder or annuity substitute when they have a decent coupon like 5%+. There are a couple now that pay that much.

I don’t like bond funds/ETFs that I might need to sell out of at a permanent loss.

DYOR and never ever a recommendation, but I came across a system a while back as follows: Bond exposure % = capped at lower of:

– Age

– 50%

– 10x aggregate bond Yield To Maturity

So:

– if you’re 20 and bonds yield 4% p a. to maturity then that’s a maximum of 20% in bonds;

– if you’re 80 and bonds yield just 1% then that’s a max allocation of 10%,

if you’re 90 and bonds have negative YTM then that’s 0% bond exposure; and

– if you’re 60 and bonds yield 7% to maturity then that’s a max allocation of 50%

This:

– Keeps you out of bonds when they offer return free risk (no return, only risk)

– Minimises exposure when they offer little (but some) return relative to risk

– Maximises exposure when they offer more return for risk

– But prevents bonds from crowding out other assets (regardless of relative or absolute valuations), thus maintaining some cross asset class diversification

– Recognises the importance of age in asset allocation without letting it dominate over other issues related to returns, risks and diversification.

@TA (#44)

AFAIK, for the retail investor, duration matching is probably as good as it gets. There is a lot of work out there, typically highly mathematical and geared towards institutional investors, that looks at bond portfolio immunisation. A recent(ish) paper, “Immunization Strategies for Funding Multiple Inflation-Linked Retirement Income Benefits” (Simões et al., 2021) contains an extensive introduction to the subject with plenty of further reading as well as an interesting study.

Since it seems to be a niche case, I have yet to find anything in the literature dealing with the specific application of locking in annuity income, but one problem is that the duration of the annuity can only be estimated by assuming a) mortality rates, b) a yield curve, and c) fees that may or may not be used by the insurance company. That different companies use different assumptions can be inferred by the different payout rates available (e.g., at the beginning of November, single life RPI annuities at 65yo had payout rates ranging from 4.87% to 5.24%, and at 75yo from 6.5% to 7.4% – this is the reason why shopping around is highly recommended!) and, therefore, durations would also differ (with ‘by how much?’ being the obvious question to which I currently don’t have an answer).

A couple of points:

Bonds are not safe and you can lose a lot of money with them as recent history has shown.

Post market crash when equities recover, this is often a good opportunity to make very good, double digit returns even in index funds.

The worlds greatest investor recommends a 90:10 ratio, do you want to rely on all these pundits with their graphs who disagree?

@Alan S – Much obliged!

@Semipassive and DH – it would be interesting to test some of these rules. However, if you’re approaching retirement, and are vulnerable to sequence or returns risk, I think you’d live to regret not derisking if equities crashed 50% or more.

The sensible choice when yields are on the floor is surely to shorten your duration. Hold short bonds, hold cash. Actually @SemiP – I think this is what you’re saying on a second read of your comment 🙂

By implication, you’d also want to load up on long bonds in the mid 1970s when long bond yields were 15%. Who amongst us would have been so brave with annual inflation running over 20%?

@Warren – no-one here claims bonds are safe. Take a look around: https://monevator.com/bond-market-crash/

However, the objective under discussion is how to derisk an equity heavy portfolio lest you’re caught up in a large stock market crash. If that’s your goal then government bonds are a big part of the solution. You can limit the risk of large yield rises by holding shorter duration bonds / leavening with cash.

Your namesake, Warren Buffett, did not recommend a 90/10 ratio for all. It was widely reported that he recommended 90/10 for his wife. I don’t know but I’m gonna guess she isn’t too worried about running out of money.

One of the things I’ve tried to stress in this series is there is no one-size-fits-all solution to this problem. Each of us should choose the asset allocation that balances our personal blend of risks.

Personally speaking, I could not afford a 90% stock allocation on the eve of retirement because a 45% loss that took a decade or so to repair was more than I could stomach.

@The Accumulator – I think it should be made very clear what type of bonds are recommended when we discuss ratios as they can behave very differently. Newbies in particular need to understand that they can be very risky, despite what IFAs and stockbrokers, say. A big weighting in the wrong type of bonds is not a good suggestion.

Warren’s wife was 67 at the time of his letter when he recommended a ratio of 90% S&P 500 and 10% short term government bonds. As you say she doesn’t need to take unnecessary risk, he could have suggested 100% cash or 50:50 but his advice was 90:10. However, I still find it interesting because it is so different to what so many experts recommend. You have to be careful you don’t miss out on better performance because you’re worried about volatility or a sustained downturn which may never happen. Being cautious is an expensive indulgence.

@Alan S & others – re: the annuity puzzle

Thanks for your information on this – I understand what you say – I assume you work(ed) in pensions/insurance/finance industry and if so, you may not like what I say below but I am not directing this at you obviously, but at the finance industry and financial advisors in general as I have, unfortunately, had only bad experiences with them.

Since 2015 when pension freedoms came in annuity purchases fell off significantly. While 90% of DC pots accessed in 2013 were used to purchase an annuity, this figure has fallen and appears to have stabilised at only around 12% of pots since April 2015 (FCA). When given the choice, many individuals simply do not annuitise. So why is this?

There are many reasons for this but in my view one of the biggest is lack of trust in the insurance/pensions/finance industry in general. They are probably up there with politicians and IFAs as the biggest “legal crooks” in general – @TI did this article on them back in 2010:

https://monevator.com/financial-advisors-swindlers-and-leeches/

I appreciate that article was before the new rules regarding fees etc. came in but I still wouldn’t trust them with a bargepole – and why would you need them anyway if you can fare better with a passive approach (as most do with a bit of reading on the internet). I would much rather handle my own affairs anyway – even when I was working I ditched my accountant as he was doing a bad job and making too many mistakes.

I think insurance/pension companies are seen generally as higher up on the untrusted list than even motor mechanics/banks/solicitors/builders/roofers (even though I worked most of my life as a contractor in the construction industry).

Although not specifically annuities (but affects these insurance companies just the same) recently the consumer group Which? submitted a super-complaint to the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority in September 2025 “targeting systemic failures in the retail home and travel insurance markets, highlighting poor claims handling, misleading sales, and a lack of enforcement by the regulator. It’s a broad challenge against widespread consumer harm, not specific firms, demanding the FCA investigate market-wide issues and enforce better consumer protections, with the FCA having until December 2025 to respond.

Key Details of the Complaint:

Targets: Systemic problems in home and travel insurance, not individual companies.

Main Issues:

Poor Claims Handling: Customers face low acceptance rates and unfair treatment during claims.

Inappropriate Sales: Policies are often confusing, leading customers to buy unsuitable cover.

Regulatory Failure: The FCA isn’t doing enough to tackle these deep-rooted issues.

Request to FCA: Take enforcement action against non-compliant firms.

Launch a market study to understand the root causes of poor outcomes.

Work with the government to review existing consumer protections.

Why it’s a “Super-Complaint”:

This is a rare legal tool used when a consumer body believes a whole market is significantly harming consumers” (like Which?’s previous successful action against BANKS OVER TRANSFER FRAUD).

This is the main reason I regularly change banks – especially if poor service and I don’t have insurance products/warranties either other than I am legally obliged to (such as motor ins). I don’t have any home insurance now for quite a few years and so far I am better off and accept the risk of large one off fire/flood event etc. I did this after talking to someone I know well, whose family had a large number of let properties they owned and they didn’t insure any of them as they didn’t believe the high premiums were worth it and never had any major problems. There is always a chance of course but I accept that. This is also the same with warranties as I’ve never had anything fail within its expected lifetime where I could have used the warranty they tried to sell me.

I think an annuity is similar sort of warranty insurance that is just protecting you against a risk that for *most* people just doesn’t materialise. Most people die with money and a fair bit for those that save and invest and watch the pennies, such as those of us who read investing websites.

In my own lived experience I have found that insurance/pension companies cannot be trusted often misleading customers and having practices of concealing fees/charges and other extractions from customers’ funds in an underhand way i.e. not making it clear what is actually being taken from funds upfront. I was hugely misled back in the day, when I took out various personal pensions (and cash ISAs) with an insurance company which is still around to this day. Sure they tell you in your annual report what the AMC fees are but then fail to tell you clearly what else is being extracted from your funds by the “back door” in other not so explicit charges – all sorts of things and commissions including their own financial representatives charges for coming out to sign me up for the policy which I had no choice in and which they didn’t inform me of until after I had signed and taken them out. I lost out for over 30 years not realising why the funds under performed and when I asked they made excuses but failed to advise of all the hidden charges. I trusted them too much and in what my very jovial insurance company financial representative/advisor told me. These amounts were colossal over the years.

Since I finished work and had more time to look into my pensions and transferred them all out in 2021, I went down the passive/DIY investment road since which they have performed much better in DIY low cost investments, even though I’m a total amateur and have not ever worked in the finance industry. Even then if there was not the better regulation, I’ve no doubt at all that investment platforms would treat us just the same and hide much more stuff from us. I mean most mainstream investment platforms that charge fx fees, still don’t tell you in pounds and pence what fx charges you are paying on say, global tracker dividends. You get your divi paid with no mention of any charges. None of the (quite a few) platforms I invest with provide these – when to be upfront/clear they should inform you exactly what the fx charge is at the time you get it. They simply drop you the divi with the fx already deducted but no mention of any charges taken at all. One investment platform, a large bank (HSBC), I rang about it – wasn’t even able to tell me what percentage they charged for fx and said it just “varied” – what are they talking about – just for a relatively small 1k odd amount of dividend they should be able to tell me exactly and they could? Sure you can find this out and work it out yourself if you have to, but many newer investors may not even realise they are paying it when really these days (and how many scandals later) it should be law to disclose all the charges paid at the point you suffer them. They don’t do this. Where’s Martin Lewis when you need him!

So with annuities I think longevity risk, which they mainly protect against, is overrated, many people like myself do want flexible/liquid funds to spend when they wish – maybe a larger proportion in the next few years and relatively a lot less from 70 ish as I know by my own family. Many think, as myself, that retirement spending is front end loaded so much more money will be spent in your 50’s/60’s than 70’s/80’s onwards with health conditions being a factor from around age 63 apparently limiting what you can do – I started with some in my 40’s which was a reason I retired about 50. So for me I don’t want just the same monthly payout for the rest of my life (which could be just a few years anyway for all I know) – I don’t really know what I will need so why box myself into a corner?

I think many people think the same as this. It’s hard work saving/investing (with maybe some frugality along the way to achieve) whilst working and at retirement many feel you need to enjoy your fruits before it’s too late like it was with my mother/father. They had personal pensions which they had to annuitise back then and they both didn’t live long enough to recover their money – I helped them sort out their annuities at the time. If they could they would have been better off keeping their money. They still died with plenty of money though – sadly weren’t in good enough health in their latter years to enjoy it then. I did warn them to spend it earlier whilst they could but I accept parents don’t listen to their kids.

Someone else on here said with DC all your funds will just end up going to the local dogs home. I can assure you mine won’t (not an animal lover anyway) – and my will says otherwise and I would rather a dogs home benefit anyway than it be swallowed up by an insurance company (or the Govt) any day of the week. As I said insurance/pension companies are not in the business of losing money, so the majority of us, on average, will pay in one way or another, by losing our money to them whether this be in fees/charges of some kind or our funds lost to them as opposed to fewer people that gain, come off significantly better and live to 85 -90 yrs plus. When I looked at mortality figures just now for my age/male it said this:

“recent data (2021-2023) suggests I can expect to live roughly another 20-21 years, reaching an average age of around 77-78, though this varies by region and reflects slower increases than pre-pandemic, with many living longer, often into their 80s or beyond, depending on health and lifestyle.” I did read somewhere recently that mortality ages had been affected since the pandemic.

Just from a personal point of view, I don’t believe an annuity at any age would be worthwhile as I believe my funds will outlast me anyway – although they are more volatile/equity heavy but not longevity in the family/I already have some health conditions even though never smoked/don’t drink and do exercise etc. Also my partner and myself both already have an annuity (full 35 year contributions) for the post 2016 state pension of nearly 24k (if we ever get to that age and the govt hasn’t changed the SP rules) and I will not personally need any additional income floor I don’t believe (I’m not a fan of these anyway – difficult anyway to ascertain what exactly that will be over a 20-30 yr average retirement). At todays rates our S.P. will cover all bills/food and extra would only be needed if doing a fair bit of travel, large one off expenses like cars/household repairs and such etc.) If and when we get our SP, my SWR would then only need to be around 1.7% max, maybe less, for a more than comfortable lifestyle (with the only factor being the volatility of my funds). I know the story is I should retreat into fixed interest/bonds and although I do have a fair bit in cash, I don’t want bonds or linkers. Like many I don’t like bond funds, they’re the only things in passive investing I’ve ever lost money on and just don’t favour them. Likewise I just can’t be bothered with linker ladders – they’re too much hassle for me. I’m not an investing hobbyist in any way, I’d rather be doing something else than spending my final years on this earth poring over them – just not any interest. Passive investing is supposed to be easy/simple for DIYers without spending inordinate amounts of time fashioning/managing. Besides life doesn’t pan out to a plan – as with me things change part way through from what you intended/health conditions turn up/stuff happens and your spending likewise changes. I think trying to estimate/plan a lot of your needs/spending to the n’th degree is largely a waste of time. If things are inflexible then you don’t have options of bringing forward spending plans if you require much larger amounts sooner – say if you suddenly become ill or for whatever reason need more to go and live elsewhere (well this country isn’t getting any better is it?) Okay so your plans could be more flexible by doing a combo say (linkers/annuity/DC) but not everybody has the funds to do that justice and so doesn’t want to be pinned down with an inflexible annuity. To me the idea of irrevocably exchanging a flexible lump sum for an inflexible future income stream is not an idea I’d ever be comfortable with. From my past experience I like to retain full control over my assets rather than some insurance company. I think these are clearly some of the main reasons why only 12% of people choose to purchase any annuities nowadays.

@Warren (#51)

I agree that there is a big difference between the behaviour of fixed income ‘funds’ of different maturities and this ought to be mentioned. Short maturities (including cash) will tend to do best when rates are rising (e.g., 1940 to 1980), long maturities when rates are falling (e.g., 1980 to 2020) with the performance of intermediate maturities lying somewhere between the two. The problem with the most common gilt fund index, i.e., ‘all stocks’ (which holds all nominal gilts proportional to their issue weights) in the run up to 2021 was that its duration was comparatively high (lots of long bonds issued, low yields, and low coupons) and therefore the subsequent increase in yields led to a strong decrease in NAV.

The ‘right’ sort and amount of fixed income may very well depend on whether you are an accumulator, close to retirement, or retired and, when retired, what proportion of your required income is already guaranteed (i.e., SP and/or DB pension).

To reverse the meaning of your last couple of sentences. You have to be careful you don’t miss out on better performance because you’re hoping for sustained equity growth that may never happen. Being adventurous can be an expensive indulgence!

Why 90/10? I have no idea of WB’s thought processes, but a look at SWR as a function of equity allocation for US retirees, indicates a fairly flat region until 90% stocks (e.g., see Figure 2 of Pfau’s paper, “An International Perspective on Safe Withdrawal Rates: The Demise of the 4 Percent Rule?”). Figure 1 of the same paper, shows that, not surprisingly, it was the 1929 crash that lowered the SWR at 100% equities.

@AS (#52)

An interesting read of your perspective. Just a few points

1) I was a scientist/engineer who only became interested in finance in the run up to retirement. So, no problem for me. My own experience of the insurance industry (mainly pet!) has generally been good.

2) According to the ONS Life Expectancy Calculator, life expectancy in the UK at 57 (my guess at your age) is around 84yo with a 10% chance of reaching 97yo. The probability of one or both of a couple reaching 100yo is also about 10%.

3) I’d agree that the SP forms sufficient income floor for the vast majority of UK retirees.

@Warren – thank you for being a good sport and engaging. I think this is a useful discussion and – reading between the lines – we’re basically in agreement. I totally agree that bond types and maturities are all important. I’ll get into that in detail in the next episode of the series. But I concur that the whole “bonds are safe and don’t worry about the details” message pre-2022 was a costly oversimplification.