The government has revealed a new plan to get more houses built – and to enable more of us to buy them.

But I think it’s better news for shares in house builders than for the young, would-be home-owning masses.

Theoretically, first-time buyers will benefit from the new scheme to get the market for 95% mortgages going again.

The plan will see the government acting as guarantor of high loan-to-value mortgages, in conjunction with house builders, as The Independent reports:

The Government will underwrite a small percentage of each loan on newly built property. Banks are typically demanding a deposit of 20 per cent on loans to first-time buyers and, by guaranteeing a portion of the loan, the Government will in effect be shifting that “loan-to-value” ratio so that the borrower needs a smaller deposit – possibly as little as 5 per cent.

That, it hopes, will lead to more demand and provide a boost to the construction industry in terms of sales and employment.

As I understand it, the government is proposing that in order to achieve a 95% loan-to-value mortgage, a house builder would contribute say 3.5% of the property price and the government another 5.5%.

Together they’d be putting up 9% of the purchase price. Therefore to grant a buyer with a 5% deposit a mortgage, the lender would only need to put up 86% of the purchase price (100-9-5 = 86%).

With banks still hoarding all the cash they can, that’s a much more attractive deal for them than having 95% of their capital at risk.

High loan-to-value mortgages mean big risks

As a potential home buyer, however, the first thing to note is it’s you – not the government – who is first in line for losses should you sell your house for less than you paid for it.

I think that’s only right – a scheme protecting buyers 5% deposits would be untenable, giving a free option on house price rises.

Still, it’s likely to be misunderstood by some people. I remember that when so-called Mortgage Indemnity Guarantees (MIG) were in vogue in the 1990s – before reckless banks stopped bothering to account for the extra risks of high loans – there was little clarification in the mortgage documentation that the MIG protected the lender, not the person paying it.

But a more important question is whether new home owners should actually be risking taking out a 95% mortgage on a new build property, even as prices stagnate across much of the UK.

New build houses generally have a premium price, which lasts about as long as the leathery smell of a new car before they start depreciating.

Banks therefore don’t like lending 95% against the value of a new build property, for the very sound reason that any particular aggregation of laminate flooring and beech kitchen units is unlikely to be worth quite as much again until house price appreciation papers over that lost premium.

And outside of prime London, house price appreciation is notable by its absence.

While I understand the frustration many feel at not being able to buy a home, taking out a 95% mortgage on a new build property that the government is effectively bribing banks to lend on seems a risky way to go about it.

Buying the shortage of houses

Given the new climate of financial responsibility, it seems strange that the government wants to encourage high loan-to-value mortgages just a few years after the collapse of Northern Rock.

A cynic might say it amounts to State-sponsored negative equity!

A few years ago I would have suspected it was all part of a ruse to prop up high house prices. But having been repeatedly humbled by the strength of the London housing market – easily my most costly financial misjudgement – I’m nowadays less cocksure about the path of house prices.

Specifically, I now accept that there’s a structural shortage of homes for people to buy.

Note that’s subtly different from saying there’s a lack of places to live in. While rents have increased in the past couple of years as up to one million people have had to rent a home who would previously have bought a house, I’m not convinced there’s not enough rooms with beds in them for the UK population.

I now agree though that there’s probably a lack of properties that people want to buy, in the places that people want to live.

And while you might argue market forces should be the best way to fix this, I’ve come to the view that there are structural reasons why this isn’t happening.

Some evidence for this is the difference between the path of prices in the US and the UK.

Both countries experienced booms – indeed ours was much bigger – and both have seen new housing ‘starts’ derailed in the recession. In both countries mortgage holders have benefited from cheap money, too (at the expense of prudent savers, but that’s another issue).

Yet whereas US prices have fallen back to more sustainable levels in most areas, in the UK prices still seem stuck above both historical price-to-earnings ratios, and also higher than many pundits would have predicted given the low turnover of property.

The rise in the cost of renting – while clearly egged on by an influx of thwarted first-time buyers – also indicates that at the least there’s not a surplus of houses sitting empty.

All this was pretty much outlined in the much-cited Barker review of 2004, but I have to admit I was an avowed housing bear in the mid-2000s when it was released, and I thought Barker had under-estimated the impact of easy credit on house prices.

While I haven’t exactly done a U-turn, the housing market hasn’t crashed as I’d predicted it would once the taps were turned off, especially here in London.

When the facts change, you have to consider changing your mind.

The case for investing in house builders

Perhaps easier to predict than the path of house prices though is the fortunes of UK house builders.

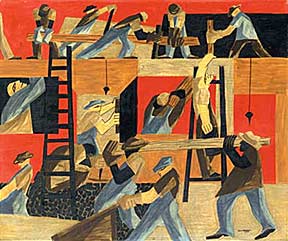

House building volumes have collapsed from pre-crisis levels, which were themselves too low for all the new household formation going on in Britain:

With divorce and single living still in the ascendant and net inward migration hitting a new high of 252,000 in 2010, the need for extra homes just keeps on rising.

I therefore think house builders will enjoy plenty of demand for new houses to keep them in business for the next few years, even without a return to go-go price rises.

The share prices of house builders collapsed by 90% or more in 2008 and 2009. While they have recovered a bit, they still look cheap given that most now have far stronger balance sheets thanks to big rights issues and asset sales.

All the main builders have now returned to making profits, with their margins being helped along by the cheaper land they bought in the downturn. Margins are also up because today’s lower levels of activity enables them to haggle with their suppliers, and with the various tradesmen.

Yet the price-to-book values of house builders – a measure of how much you pay for a company’s assets – are still well below 0.5 in the case of the volume players like Taylor Wimpey and Barratt Developments.

Theoretically that means you get £2 of assets (such as land and properties in development) for every £1 of shares you buy.

True, these volume builders still carry a fair bit of debt. If you’re more risk averse you might want to investigate shares in the likes of Bellway and Redrow. They are more lightly-geared, and should better withstand the impact of a renewed recession.

Alternatively, you could wait for a dip and consider buying my favourite company in the sector, Berkeley Group. You’ve already missed a nice rise though, and the company doesn’t look half so cheap as its rivals. I continue to hold its shares for the long-term, and consider management in a different league to the competition.

Investing in property mad Britain

Interestingly, share prices in the builders actually fell on the news of the government’s plans.

Perhaps the market expected more of a bail out from Cameron and Co, or perhaps investors are concerned about the money that builders will need to invest as their part of the guarantee scheme.

It’s worth noting, however, that most house builders are already on the hook should house prices fall with renewed vigour.

Not only will their land holdings be written down in value again, but many have been undertaking shared equity and part-exchange business, which has seen them retain housing assets on their books. You should definitely dig deeper into the accounts if this makes you nervous and you’re considering investing; my point is the few percentage points of extra risk they’d retain with the new scheme isn’t wildly different to what some are already doing.

Whatever the stock market thought this week, though, I think the outlook for shares in house builders in the medium term from today’s depressed levels is pretty bright.

The government clearly wants more houses to be built – if only for the economic activity it generates – and most of us seem happy to keep paying an awful lot for those houses. Planning changes should also play into the house builders’ hands.

No guarantees, but I think their share prices will likely be much more upwardly mobile than general house price inflation over the next few years.