Last year’s stellar returns for UK passive investors came with a snag: What goes up can come down.

Global trackers and all-in-one products like the Vanguard LifeStrategy fund delivered superb returns last year. But this was in large part due to big moves in the exchange rate.

UK listed shares only account for about 7% of the world’s total. Global funds and similar diversified portfolios therefore hold as much as 93% of their money in non-UK shares. These shares are valued in foreign currencies.

As such currencies strengthened against the pound after the EU Referendum, the value of overseas shareholdings soared when translated back into sterling for British investors.

These currency gains came on top of any moves in the underlying stock markets.

So, what’s the problem? Who doesn’t like a 20% windfall gain? Making money from Brexit at least takes the edge off shouting at Question Time.

Also, this so-called currency risk is considered part and parcel of global investing in equities. I’ve explained before how it can diversify your portfolio. When risk works in your favour, it can seem about as scary as a fairground ride.

But how would you feel if the pound suddenly strengthened?

What if your portfolio fell by 20% in a year, even as global markets rose?

A test of passive purity

You might sensibly shrug and say you’d live with it. This is perhaps easier to do after receiving such an unexpected windfall.

Many professional investors and academics say long-term equity investors can probably ignore the swings and roundabouts of currencies and markets, anyway. For various reasons, they tend to work themselves out over time. (I’ll cover why in a follow-up post).

Passive investors especially might baulk at being DIY currency speculators.

Why do you know better than the market about the future of the pound?

What reason do you have to think it’s set to reverse and squash your overseas gains? Full-time professional traders clearly think otherwise.

Monevator contributor Lars Kroijer would say the pound’s weakness reflects the best guesses of countless expert investors putting their money where their mouth is. You bought a global tracker fund to let this combined wisdom decide where your money was best invested.

If you had no edge when you first opted to invest passively and globally, what’s changed?

That’s a very credible attitude. Business as usual is simple, practical, and it keeps the door to active meddling firmly closed. It could be better for your returns, too.

I would offer two counters.

I didn’t sign up for this!

Firstly, the pound’s collapse largely reflects the fear that we might have holed our economy below the waterline with Brexit.

Britain has a precarious current account deficit. We also have an economy reliant on a financial sector that looks especially vulnerable to a clumsy divorce.

We can hope – and try to negotiate – otherwise. But the vulnerability is there.

However some of the pound’s fall might also reflect excessive fear that something very bad could happen, more than the most likely scenarios.

To the (unknowable) extent that’s true, the decline could be overdone due to emotion and political risk. You might wonder whether as an investor you’re likely to be compensated for taking this additional risk?

Secondly, remember the other word for risk – as academics see it – is volatility.

You might intellectually accept research that says long-term global equity investors can usually ignore currency risk.

But that doesn’t make it easy to see your wealth rapidly rise or fall 20% as your country goes through the political wringer.

Such discomfort might make you sell your shares, or at least reduce your rate of saving. It could thus hinder progress towards your long-term goals.

And that’s sub-optimal, as my old maths teacher used to say.

Three responses to currency risk

As I see it, we have three main choices as to how to respond to the sharp currency-based gains many of us have enjoyed recently.

Option 1. Keep on keeping on

A great option and as said I have no argument with it. Changing strategy because something spooks you is not really what passive investing is all about. Fiddling is trying to be smarter than the market.

Perhaps you could think of the risk of your overseas assets falling if the pound strengthens as an insurance policy against a UK calamity. Some analysts reckon the pound could fall to parity against the dollar if Brexit turns ugly.

I don’t expect that, but what do I know? And insurance is never free.

What if you’re a newer saver and investor? Yes, it might turn out you’re buying foreign shares on a relatively costly basis because you’re using temporarily weak pounds. But you won’t remember or notice in 30 years time.

Also, while you haven’t seen the huge big gains from the pound’s collapse enjoyed by older investors with large diversified portfolios, you equally have much less of your lifetime wealth now at risk from a reversal.

You have years of savings ahead of you, and only a little on the table. Why sweat it?

Option 2: Sell overseas holdings, and maybe buy British

Still here? I guess you’re worried the pound will strengthen, and you want to do something about it.

Maybe you’re approaching retirement and you want to lock-in the currency gains, reasoning you’ll be spending pounds not dollars or euros in your dotage.

Or maybe you fancy yourself as the new George Soros, and you think the pound has fallen far enough.

Well, the easiest way to reduce currency risk is simply to sell some of your overseas and foreign-denominated holdings.

You could keep the money raised in UK pounds and bonds. This would also reduce risk in your portfolio overall, as you’d own fewer equities. As The Accumulator wrote last year, it’s worth considering if the gains of 2016 left you feeling vulnerable.

Alternatively, you could reinvest the money raised into UK shares or funds.

This isn’t a terrible idea if you’re an active investor, especially a stock picker like me. Unlike my passive co-blogger, my own portfolio is my precious a hodgepodge that bears little resemblance to a balanced global portfolio. Its active share is turned up to 11! I can always find new UK shares to buy.

But there are big problems, too, with this approach, whether you’re a passive or an active investor.

For one thing the UK market has already rallied on the back of the weak pound.

The FTSE 100 generates about three-quarters of its earnings overseas. Expectations for those overseas earnings have been boosted.

If the pound rose 10-20%, the UK market would probably fall. Swapping foreign shares for a FTSE tracker might be out of the poêle à frire and in to the fuego.

You might try to avoid this by investing in smaller companies that are less reliant on overseas earnings. But they’ve largely recovered, too. You’d also be taking on the risk of doing much worse if we see a deep UK recession from Brexit.

And obviously, you’re getting far, far away from a diversified global portfolio.

Remember, as my own tongue-in-cheek maxim states, risk in investing cannot be created or destroyed. It can only be transformed.

For passive investors especially, I think there’s a better way.

3. Sell overseas holdings, and buy pound-hedged alternatives

At last, the money shot! You could swap into currency-hedged versions of your overseas holdings.

Let me stress I am not saying everyone should immediately do this, especially not to their entire portfolio. But I do believe tilting in this direction is valid.

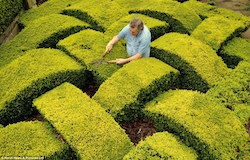

What is hedging? Hedging for investors has nothing today with shaping your privet into a cock (or a duck, for that matter). Hedging for currency purposes involves putting on a trade that mitigates the impact to your portfolio of changes in foreign exchange rates. A fully currency hedged portfolio would be impervious to exchange rate moves.

If we were big-time fund managers, we might enter into derivative-based Forex contracts and options to neutralize the impact of the pound fluctuating on us.

A global tracker fund has about 50% of its money in the US, for instance. So simplistically we could take out a hedge that protects about half our global exposure from movements in the pound/dollar exchange rate. And so on with yen, euros, yuan, krone et cetera…

Now, for reasons I will cover in the follow-up post, it’s not quite that, um, simple. Currencies and economies interact a lot. Currency hedging itself doesn’t take any of that into account. You’re just insulating your portfolio from exchange rate moves.

Okay, understood? Time to tootle down to Canary Wharf to see a man about an expensive currency hedge?

Actually I’m not suggesting that. A far simpler and more passive-friendly approach is simply to invest in currency-hedged funds.

This used to be hard and expensive. The situation today is still not brilliant, but a range of currency-hedged ETFs has made things much easier – and cheaper.

Such funds take care of the hedging for you as part of the package, at the fund management level. You just buy and sell them like any other ETF.

Hedging your overseas bets with ETFs

Consider two ETFs that track a European stock market index:

- The iShares MSCI ex-UK ETF (Ticker: IEUX)

- The iShares MSCI ex-UK Hedged ETF (Ticker: EUXS)

Both ETFs track a selection of leading stocks from European industrial countries, not including the UK.

- The first fund, IEUX, is exposed to the full force of currency fluctuations.

- The second fund, EUXS, is hedged to British pounds (GBP, in finance jargon).

This graph shows how the two ETFs have performed since early January 2016:

The red line shows the gains of the normal ETF, versus the hedged version in blue.

As you can see, the standard version of this ETF has outperformed the currency hedged version by about 20%. That’s entirely down to the weakening of the pound versus the euro.

However if the pound were to rally against the euro, then this situation would reverse.

You can clearly see currency risk in action here. This time it worked to the benefit of a UK investor, but obviously it can go the other way.

There are now quite a few such hedged ETFs available. Have a hunt on JustETF or similar.

Here are a few examples, all hedged to GBP:

- UBS MSCI Australia Hedged ETF

- iShares MSCI Japan Hedged ETF

- UBS MSCI USA Hedged ETF

- iShares MSCI World Hedged ETF

The downsides of hedged ETFs

There’s one obvious drawback of a hedged ETF. If the currency risk doesn’t go against you, then you would have been better with the unhedged ETF!

But leaving aside that hopefully bleeding obvious point, there are other issues:

Higher TERs – Currency hedging is not free. The hedged ETFs I’ve seen tend to have higher annual expenses. They’re not dramatically higher though. For instance the difference between the hedged and unhedged USA ETFs from UBS I linked to above is 10 basis points (or 0.1%) per year.

Fairly new – Hedged ETFs count as an innovation. We’ve no reason not to think they won’t work. But some passive investors prefer to see long track records.

Possibly greater tracking error – The hedging comes at a cost, as said. It also introduces more potential for tracking error, depending on the hedging approach the ETF provider takes.

Smaller Funds Under Management – In all cases I’ve seen, the hedged versions of ETFs have far smaller amounts under management. This might make them more illiquid, which could increase spreads. It could also mean some are more likely to be closed in the future as subscale, which could mess with your plans.

Restricted choice – There are far fewer hedged ETFs out there. There’s no currency-hedged LifeStrategy fund, either. When you buy a hedged ETF version to get exposure to a country or region, it won’t be the cheapest, and you won’t be able to get super choosy about which flavour of index you track.

Clearly the small additional costs associated with a currency hedged ETF will compound the longer you hold it instead of a vanilla version.

If you add hedged ETFs to your strategy for a few years while Brexit sorts itself out, slightly higher TERs won’t matter too much. But over 30 years you will likely pay a noticeable price.

This is important, given that for share investors your returns aren’t likely to be predictably higher due to hedging.

(With overseas bonds the case for hedging is clearer, as we’ll touch on in part two).

To hedge or not to hedge

Personally I’ve moved some of my money into currency hedged ETFs over the past few weeks. Not an overwhelming proportion, but enough to take the edge off in case of a sharp reversal in the pound, and to dampen overall volatility.

Should you do the same? That’s a very personal choice. This article is already extremely long, and I think there are no easy answers. (I’ll point to some academic research in part two.)

For now I’ll cut to the chase and say that in these particularly uncertain times – and after the very steep fall we’ve seen in the pound, to levels not experienced for 30 years or more – I think there’s a strong case for currency hedging 10-25% or so of your equity portfolio.

This is as much to reduce volatility / risk as it is about the pound looking cheap.

Someone is already writing a comment below about how the UK will go into a depression due to Brexit, or how the pound will plummet, or how it won’t, or how passive investors should simply follow the global market and so on.

So before you pile in, note again I am saying currency hedge perhaps 10-25%, as a rough stab.

I am not saying, “hedge your whole portfolio” or “the pound will not fall further” or anything like that.

This sort of allocation would still leave at least 75% of your equities at the mercy of currency risk. That would still provide plenty of insurance from further pound falls. It would remain a largely passive approach to currency allocations.

But, as I say, it could also take the edge off.

Be wary of anyone who makes adamant calls about currency. They may say the pound has clearly bottomed – or that it will obviously fall further.

Nothing is obvious in investing.

Think of all the recent ‘no-brainers’. How commentators told us the US stock market was too expensive to touch as far back as 2012 (it’s now at all-time highs) or how inflation would rocket after QE (still waiting).

The list goes on.

Perhaps the pound won’t bounce against the dollar anytime soon. A pound bought five dollars in the 1930s. It’s been depreciating for a long time.

Maybe £1-to-one-dollar-and-twenty-something is the new normal? Maybe we’re heading to parity?

Not easy!

This is why doing nothing (which really means leaving the genius of the largely efficient market to decide things) will work out best for most people in the long run.

But if you do want to do something in light of the puny pound, I think currency hedged ETFs are worth considering.