Gentle reader, I have a confession to make. As I have written before, a short spell working for a FTSE 100 engineering firm in the early 1980s had left me with a generous-looking pension as I approached retirement.

For years – literally decades – I had filed the annual statements, marveling at how projections of my annual income in retirement inexorably rose.

Gold-plated pension

Seven or eight years ago, the engineering firm’s pension trustees launched an early retirement enhanced benefit scheme. The hope was to persuade pension fund members to transfer out, or take higher immediate benefits in exchange for lower longer-term benefits.

They paid for a firm of financial advisers to offer advice, and calculate projections. I duly filled in the forms, wryly noted the resulting recommendation to take the money – and then I did nothing.

Why cash in a gold-plated, and partially inflation-linked, final salary pension fund?

As I turned 60, this pension had become – again, quite literally – one of my most treasured possessions, offering a retirement income of £5,000 or so a year, for as long as I lived. Even better, a reduced widow’s pension would be paid to my wife, should I die before her.

No longer. As of early April, that pension is part of my past, not my future.

Take the money

What happened? Last autumn’s bond market turmoil, in short. As gilt yields plunged in the wake of the Brexit referendum result, pension transfer values rose accordingly.

Some pension fund members were being offered transfer multiples of 30-40 times projected annual pension income. Not surprisingly, they were tempted to take the cash.

Among those tempted was former government pension minister and retirement activist Ros Altmann, who saw the transfer value of two pension schemes roughly double, with the transfer value of one scheme reportedly rising from £108,000 to £232,000, and the transfer value of another climbing from £57,000 to £104,000.

She took the money. As did, according to the Pension Regulator, about 80,000 other people.

Among them me.

Gulp

Now, a few caveats.

For a start, I didn’t get a multiple of 30-40 times that £5,000. More like 20 – but certainly a helluva lot more than the same firm had dangled in front me of a few years previously.

In part, I suspect, that lower multiple is because I wasted several weeks trying to resist the temptation.

I dallied because while I’m a fairly confident and experienced private investor, a pension transfer is a lot more than a transfer of a pension.

It’s really the transfer of a risk, and an obligation.

As a member of its pension fund, my former employer was obligated to pay me that annual income, and to shoulder the associated risks.

No longer. As of the transfer, all of that is on my shoulders, instead.

Repent at leisure

Now, not for nothing are pension experts and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) alike concerned about the increasing frequency of such pension transfers.

Just because a transfer value happens to be high is not a sufficient reason for executing a transfer. Particularly if you have no or little experience in personal investing – and even more so if one of the prime motivations is simply to get your hands on the tax-free cash.

And it’s of little help to point out that the rules governing such transfers call for mandatory advice from a financial adviser if the sum involved exceeds £30,000.

For a start, that’s arguably too high, and – perhaps more to the point – the advice that such advisers are obligated to offer can be of little help in real-world decision-making.

Short-term pain, long-term gain

What do I mean by that? Simply that central to the FCA-mandated adviser calculation is something called the ‘critical yield’, which loosely translates as the rate of return that you’d have to achieve in order not to be worse off, in income terms, after the transfer transaction.

Which scarcely figured in my own calculations at all.

I know I’ll be worse off, in the short term.

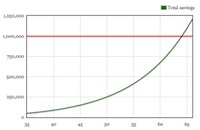

But what I’m interested in is longer-term income, longer-term inflation proofing (hopefully 100%, not roughly two-thirds), and the prospect of a six-figure lump sum to leave to my heirs. That is the trade-off in which I was interested.

Dilemma

The timing of the now-complete transfer was unfortunate. (And not solely in terms of the recent health scare which has unfortunately delayed my promised follow-up column on actively-managed ‘smart’ income ETFs.)

Basically, you don’t have to be Howard Marks – prescient though he can be – to worry that we might be in bubble territory with the stock market.

So my six-figure sum is currently uninvested, sitting there as cash, while I figure out what to do.

- Sit it out and wait for a hoped-for correction? I’ve succeeded in that in the past. But I might have a long time to wait.

- Drip feed into the market as opportunities present themselves? The trouble is, at present those opportunities seem few and far between.

- Dive in and lock in income now, rather than remaining uninvested?

What would you do? Dear reader, my confession is complete. But I’d welcome your answers in the comments below, please.

Further reading: See our article on one reader’s experience of transferring a final salary pension into a money purchase scheme.