What caught my eye this week.

Last week the major US exchanges went bananas on a strong signal that US inflation might be turning.

And that was very good news.

You know that old adage about it being important to remain invested at all times – because if you miss a handful of days you will miss most of the return?

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

These look like somewhat mediocre returns for a whole year. But they happened in 16 hours of trading.

Admittedly, I have a love/hate relationship with the old “don’t miss the best days” schtick. As a very active investor who watches the markets like most people follow their favourite football team, I feel the rollercoaster ride of a year like 2022 in my guts.

So I sometimes ponder how missing out on the best days might be worth it if you miss the worst days too. The optimal – but to be clear, hugely inadvisable – thing to do this year was to sit out the whole shebang out in cash.

(Inadvisable, sadly, because the books about successful investors who have consistently got in and out of markets wholesale for a profit would be welcome on any ultra-minimalist’s bookcase.)

Begone foul pestilence

Anyway, the inflation news is a big deal. Much bigger for markets than the US mid-term elections, which dominated the US media for fortnight.

From CNBC:

The consumer price index rose less than expected in October, an indication that while inflation is still a threat to the U.S. economy, pressures could be starting to cool. The index, a broad-based measure of goods and services costs, increased 0.4% for the month and 7.7% from a year ago, according to a Bureau of Labor Statistics release Thursday.

Respective estimates from Dow Jones were for rises of 0.6% and 7.9%.

Excluding volatile food and energy costs, so-called core CPI increased 0.3% for the month and 6.3% on an annual basis, compared with respective estimates of 0.5% and 6.5%.

Regular readers will recall I’ve been expecting inflation to ease for months. It didn’t happen. Indeed rates have gone higher than almost anyone predicted this time last year, as market expectations have been repeatedly confounded.

The result has been a brutal 12 months for pretty much everything. Stock-picking has been brutal. Some of the car crash US growth shares already down 80%-90% this year found it in themselves to drop another 10% in a day earlier this week. The proximate cause was yet another crypto crash (see the links below). But it is inflation and rates that have driven most of the de-rating in shares and the crushing of bonds this year.

And so if – and we still can’t be sure – US inflation really has turned, then we could have seen the bottom of this bear market.

US rates lever the (un)attractiveness of US markets. That sets the tone for markets around the world. The rapid pace of US rate rises also sent the dollar to lofty levels, dragging up rates around the world. All this could unwind if the threat of ever-higher inflation has been defeated.

Markets – which look forward – could move more than you’d think in response.

Leave your chickens uncounted

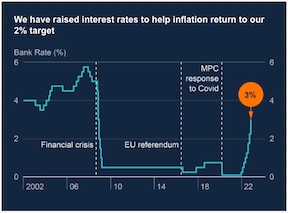

None of this means the interest rate rises are over – in the US or anywhere else.

Market interest rates moved far faster than official rates, as traders bet on the direction of travel. Higher rates from central banks still playing catch-up are baked-in, over there and over here.

But again, the top for rate expectations would be in if inflation is rolling over.

Mortgage rates – much higher than I believe central bankers would prefer – should start to ease too.

On the other hand something dumb 1 could happen again and throw this all off course. Or the CPI numbers could get revised. It’s an unpredictable world, and investing is all about uncertainty.

Which is why, despite everything, it’s best to stay mostly invested.

Have a great weekend all.

- Like the war in Europe.[↩]