This article on the pros and cons of a Family Investment Company covers some nuanced issues around accounting and tax. It will not be relevant to the finances of 99%+ of readers – though we expect many more of you will find it interesting, and anyway we want the 99% to understand what the 1% are up to. The article is certainly not personal guidance. You should not act on ANYTHING in this post without seeking professional advice. This article is for entertainment purposes only.

Can you avoid dividend tax by investing through a limited company – specifically by investing via what’s sometimes called a Family Investment Company (FIC)?

And with the pending cut in the dividend allowance to £500, is it worth setting one up, pronto?

I’ve been running a Family Investment Company for nearly 20 years. In that time I’ve made many mistakes, and been asked many questions about the structure.

Today I’m going to answer (nearly) all of them.

It’s a long one. Grab a coffee. Maybe pack some sandwiches.

Family Investment Company 101

Here’s a somewhat idealised scenario for a potential Family Investment Company owner:

- You’re an additional rate taxpayer and you expect to remain so for the foreseeable.

- You have a £1m portfolio of dividend-paying equities held outside any tax shelters. 1

- Your £1m portfolio yields 5%.

- That’s £50,000 a year of dividend income.

There currently exists a £2,000 dividend allowance (falling to £500 soon). At the additional rate tax band you pay a 39.35% dividend tax rate.

- (£50,000 – £2,000 allowance) * 39.35% = £18,888.

Subtracting that tax from your £50,000 of dividends leaves you with £31,112.

Why is this portfolio so exposed to tax?

In this scenario you’ve already used up all the other tax-efficient wheezes.

You already fill you and your spouse’s ISAs every year. You’re both over the Lifetime Allowance (LTA) in your pensions. You’ve paid off the mortgage. You’ve maxed out the kids JISAs. You have £50,000 worth of premium bonds each. You’ve realised VCTs are a rip off…

…you get the idea! You’re out of options for sheltering your investment income.

If you do have any of these other options left, then you can stop reading right now. A Family Investment Company is going to be much more hassle.

However if you are out of alternatives, then you could use a limited company to defer – and perhaps avoid that dividend tax.

But before we dig into how it works, there’s a couple of things you need to be familiar with.

UK corporation tax for limited companies

UK companies pay corporation tax (CT) on their profits (at 19%) and pay dividends to their shareholders after tax.

Corporation tax is rising to 25% in April 2023 (to pay for Brexit). But that doesn’t matter for us from a FIC perspective, because our limited company doesn’t intend to ever pay it.

Companies don’t have to pay corporation tax on dividends that they receive from their shareholding in other companies.

Why? Because the company that made the profits has already paid the corporation tax. The exemption avoids double taxation.

Realised capital gains on those shareholdings, however, are taxable at the corporation tax rate. And this has serious implications that we’ll come to later.

Directors’ loans

Directors can lend money to their company. If there’s no interest charged on the loan – and as long as the company owes the director money 2 – then there are essentially no tax consequences, for either the director or the company.

By simply keeping a spreadsheet of loans and repayments, you can just wire money in and out of your limited company.

That’s all the tools we need to make the Family Investment Company route potentially attractive.

Enter the Family Investment Company

In our stylized example:

- We set up the FIC with, say, £1 of share capital and ourselves as sole director.

- The company is furnished with banking and brokerage accounts.

- We lend the company £1m.

- And then transfer that £1m to the company brokerage account.

- We buy a magical share that pays out a 5% dividend yield and has absolutely no price volatility. (Let me know if you find one!)

- Every year the company receives £50,000 of dividends and uses that cash to repay the directors loan.

The cash flows look like this (with costs ignored for clarity):

Your company receives £50,000 a year in dividends (tax-free), and uses the full £50,000 to repay the director’s loan. You therefore receive £50,000 per annum from your £1m invested instead of £31,160. Saving yourself £18,888 per year – or £377,760 over 20 years – of tax.

(I ignored the change in dividend allowance, again, for simplicity).

Getting the million back… after tax

At the end of 20 years – with the director’s loan having been paid off with the dividends – you’d obviously like your £1m back, please.

How do you do that?

The company sells its shares (for zero profit, so no corporation tax), and pays out the £1m cash as a dividend. On which, of course, you need to pay 39.35% dividend tax, so approximately £393,500.

Hence you’ve not actually avoided any tax at all! (Nor mitigated tax, which is a better way to think these days).

We didn’t even include the various costs to pay. In fact we seem to have gone to a great deal of trouble to simply enrich our accountant.

And this is the main objection to this structure. Because whatever you may have heard, a Family Investment Company does not necessarily avoid dividend tax at all, but merely defers it.

Is deferral useful? Well… it depends.

My Family Investment Company

Let’s move beyond our stylized example, and get down to the nitty gritty.

But first an important reminder and disclaimer:

Wealth Warning You should not act on ANYTHING in this post without seeking professional advice. This post is for entertainment purposes only.

What’s the point of deferring tax?

Once money is gone it’s gone. Obviously I’d rather avoid the tax altogether, but I’ll take deferral if that’s the only option.

The Family Investment Company structure essentially enables me to choose the timing of the tax incidence of the dividends. And the FIC decides to pay me dividends when I’m paying the 8.75% rate, rather than the 39.35% rate.

I’ve enjoyed a feast-or-famine career – years when I’ve earned a great deal of money, and years when I’ve earned nothing at all. Dividend payments from the FIC can be stuffed into the lean years.

I have no DB pensions (sadly), so I can control the timing of withdrawals from my SIPPs. There will potentially be years in retirement when I can engineer being a lower-rate taxpayer.

Unfortunately, obvious wheezes like moving abroad for a year don’t work – there’s a specific anti-avoidance rule for ‘close companies’ in this situation.

Winding up the FIC at CGT rates may be possible. But I’ve never done it, so can’t attest to the process.

What if taxes go up?

You can certainly make a reasonable argument that deferral is bad – because taxes in the future will be higher than they are now.

My personal experience is taxes only ever go up. The dividend allowance cut itself is a case in point.

- Allowances are cut, or withered away by inflation, or ‘tapered’, or ‘withdrawn’.

- Reliefs are removed, restricted, or ‘means-tested’.

- Lifetime ‘Allowances’ are introduced, where before you didn’t need to be ‘allowed’ at all.

- Taxes are ‘simplified’ in a supposedly neutral way, and then the motivation is quietly forgotten and rates ratcheted up a few years later.

- The indexation allowance is removed because we no longer have inflation.

And so on. It only ever gets worse.

Given that the only escape from this is economic growth – something both the UK government and the opposition now appear to be ideologically opposed to – there’s every reason to expect taxes to continue to rise. Indefinitely.

In which case you’d be better off paying taxes now rather than later. And not bothering with a FIC.

How is my Family Investment Company structured?

I’m the sole director. My wife is the company secretary. I own about 30% of the shares. My wife 25%, my children the remaining. My wife and I therefore control the company.

One of my kids is an adult, the other is not.

We have ‘Alphabet’ share classes. Different individuals own different mixes of share classes.

There is some flexibility around paying different levels of dividends on different classes. Lower tax-rate shareholders may happen to enjoy larger dividends than other shareholders. This is slightly complex to set up and the consequences of getting it wrong can be severe, but it does provide some flexibility.

For example, family members may be having a career break, or be in full-time education.

We didn’t pay dividends to non-adult children though. In the opinion of my accountant, this is generally treated as parental income for tax purposes.

How does a FIC compare with setting up a trust?

I’ve no idea. I Googled around a bit and I didn’t think there was much in the way of tax benefits to trusts. That seems to be more about control of assets.

I would say that the directors of a company, if the articles are drafted properly, have a great deal of flexibility to do whatever they like with respect to taking risk. That would not necessarily be appropriate in a trust where there are fiduciary duties.

Does the FIC open up inheritance tax (IHT) options then?

Not obviously. Unfortunately shares in the FIC don’t qualify for IHT Business Property Relief.

Also – and inconveniently – gifting shares in the FIC is a disposal for the giver and are therefore subject to capital gains tax (CGT). Especially inconvenient with the CGT allowance also being cut soon.

My accountant is happy with the value of the shares being the proportional NAV of the FIC at the time, for CGT purposes. So you can do this early on, before the company has accrued much value. But giving away more than 50% potentially introduces control issues.

And don’t be thinking you can just fiddle with the rights associated with each share class to make the kids shares ‘worth’ more. The tax man will see straight through this.

There’s nothing to stop you setting up a second Family Investment Company and giving 49% of the shares to your kids on day one. But then you’re doubling your admin and costs.

Our (loosely held) plan is that once the next generation are proper adults, we (or perhaps grandparents) can subscribe for shares, at NAV effectively, and gift them immediately to the (grand) kids. These are a Potentially Exempt Transfer (PET) under the IHT rules

Our intent is to do enough of this to pass majority control to them during our lifetime. We’ll then leave the minority shareholding to the generation after in our wills. (Yes, subject to IHT).

Someone has suggested holding the FIC shares in a trust… but my head hurts already.

I personally would prefer to just live forever.

Which broker do you use?

Most brokers offer a company or corporate account. We use Interactive Brokers (IBKR).

Why do we use IBKR?

Cheap margin loans. As any Private Equity associate will tell you, debt interest is tax deductible for companies. So if you’re going to apply leverage anywhere in your portfolio then the FIC is by far the best place to do it.

There was a good decade when my FIC was borrowing money from IBKR at about 2% (tax deductible), and repaying my directors loan so that I could use it to offset my mortgage (costing about 3%, not tax deductible).

You probably shouldn’t have one of these structures if you still have a mortgage though.

If you think Interactive Brokers is for you, then please DM me on Twitter for an affiliate link.

How much leverage do you use?

Lots! Between 50-100%. (Where 100% means the FIC owns £100 of stocks for every £50 of capital)

When interest rates were very low – and the interest is an allowable expense to offset against capital gains – why would you not run it hot?

How do I manage the leverage?

In theory the size of the margin loan never exceeds cash that I could feasibly access at close to zero notice and lend to the FIC as a director’s loan. We keep an effectively un-drawn offset mortgage against our Principal Primary Residence (PPR) for just this purpose.

In reality this rule has been ‘passively breached’ on one occasion, when I had to draw down the entire mortgage at the peak of the COVID slump. That was, as they say, ‘squeaky bum’ time.

(For quants-only: I also ensure that there are always sufficient available free funds in the brokerage account to cover the max of the parametric and historical two-day 99.9% Expected Shortfall.)

We’re reducing leverage now that interest rates have risen.

Which bank do you use?

Pretty much all banks offer a business account. Turn up with your incorporation documents and ID, and you should be good to go.

I’ve heard from others that banks don’t like FICs. I’m not sure why this would be, or what would cause the problem. It’s not something I’ve experienced.

If you’re only used to personal banking, then you might be annoyed to learn they could expect you to pay for things.

We use a Santander business account and don’t pay any fees, I guess because we don’t do the things you might pay fees for. (Paying in cash would be an example).

This was not an active choice. We used to use Abbey National, and it merged. Possibly our free account was grandfathered in.

What stocks do you own in the FIC?

This is my most favourite question, because anyone familiar with my stock picking skills would think I was the best person in the world to answer this question.

We’re looking for stocks that don’t go up – something I do appear to be an expert on!

Actually, we’re looking for stocks where most, if not all, or even better, more than all, the returns come from dividends.

This is because dividends are tax-free to the FIC and capital gains are not. So we want lots of dividends and the minimum capital gains – or even capital losses.

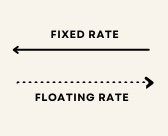

For example, all the assets below deliver the same returns, but the tax consequences are very different. (RIP Modigliani & Miller).

Stocks with high yields that never seem to go anywhere are what we want.

Why do you want to generate capital losses?

The FIC pays corporation tax on any realised capital gains, although we can offset expenses and losses.

Effectively we try to avoid ever paying corporation tax by ‘sterilising’ gains. That is, by only realising them if we have sufficient offsetting losses in some other stock, or running costs.

For this reason we want a portfolio of stocks and not just a high-yield dividend-focused ETF like Vanguard’s VHYL, for example. We’re after some dispersion of returns.

This does still lead to some shareholdings being sufficiently ‘in-the-money’ that it’s hard to have the tax capacity to sell them.

When you see the portfolio in a minute, there’s some stuff that’s been held for a very long time for this reason that is no longer particularly high yield.

Any other constraints on potential stocks?

Yes. It’s very important that the dividends are actually tax free to the FIC. There are some specific examples of cases where they are not. The source of the stock has to be a ‘qualifying territory’ on this list.

Tempted to stuff the FIC full of London-listed infrastructure or renewables trusts? Large capitalisation, high-yield, low volatility – perfect, right?

I’m afraid not. They are pretty much all domiciled in Jersey or Guernsey, and guess what? The Channel Islands are not on the list.

But most proper countries are, including, importantly, Ireland (where most LSE-listed ETFs are domiciled) and the US, with over 50% of global stock market capitalization.

However, and I’m sorry about this, but we need to talk about dividend withholding tax before we go any further.

A word about dividend withholding tax (WHT)

Explaining dividend withholding tax fully is beyond the scope of this post.

But in summary…

Most countries level a withholding tax on dividends. This means you don’t get the dividends ‘gross’. You get them ‘net’ of withholding tax.

For example, the Netherlands WHT rate is 15%, so if a Dutch company pays a €1.00 dividend, you will receive €0.85.

As an individual UK taxpayer you may be able to use the 15% as a credit against any dividend tax you owe in the UK. But as a limited company we can’t, because we don’t pay (UK corporation) tax on dividends anyway.

In theory, the tax treaty may say we can get a reduced rate. But good luck getting your broker to take any interest in that. “Sorry they are held in ‘street’ name”.

You could also ask the foreign tax man for the money back. Good luck with that, too. “Sorry, your broker shouldn’t have withheld the tax in the first place”.

So what does WHT mean for a FIC?

It is a long way of saying that we only really want the FIC to hold stocks domiciled in countries that don’t levy dividend withholding tax.

Significant countries where this is the case are the UK, Hong Kong, and Singapore – plus funds in Ireland.

Hong Kong is, of course, not on the qualified territories list, and Singapore is not very interesting.

So this leaves us with… UK-domiciled companies and Ireland-domiciled ETFs. Although we may break this rule if the (post-WHT) yield is high enough.

The ETF / fund structure doesn’t avoid this issue, by the way, it just hides it. (There’s the exception of ‘swap-based’ ETFs tracking US indices. Maybe we’ll cover that another day.)

Individual US stocks that pay dividends should be held in your SIPP, where you should pay no withholding tax.

We also want to avoid things where the distributions are interest not dividends, because interest is taxable for the FIC.

So we might buy preference shares – although they are usually not marginable – because they pay dividends. But not AT1 bonds, because they pay interest.

Great, but what have you actually got?

I just alluded to another, personal, constraint – I want my stocks to be marginable at IBKR. Which means big and liquid.

I’d also prefer they were denominated in GBP and paid their dividends in GBP because otherwise it complicates the accounts. This is not much of an additional constraint given the dividend withholding tax issues above.

I’m left with a portfolio that looks very much like the sort of thing a classic UK equity income investment trust might own.

What can I say?

GACA is the only non-marginable share. And I think we can all agree there’s not much danger of these stocks going up much.

Aren’t you letting the tax tail wag the investment dog?

Yes, absolutely, I am. But look at it this way – maybe my portfolio outside the FIC is the global market portfolio minus these stocks in these weights?

I mean, it’s not, obviously, but it could be.

We’re aiming for this:

How actively do you trade this portfolio?

I have an ambition to go a whole year and not do a single trade. I’ve not succeeded yet. We do a handful of trades a year, but some of these positions haven’t changed in at least a decade.

Do companies still benefit from the ‘indexation allowance’ on capital gains?

Sadly not, this was quietly removed in 2017. In my opinion it made the FIC structure substantially less attractive.

What other expenses can I get away with charging to the FIC?

One way of essentially withdrawing money tax-free is to have the FIC pay expenses that you would otherwise have to pay yourself. (‘PA’ as they say).

These effectively get you, as an individual, ‘tax-free’ money out of the company, and are tax deductible for the company. A double win.

The extent to which you can do this appears to be down to the judgement of your accountant. You have to be able to make the case that it’s for legitimate business purposes.

We don’t do as much of this as we should, probably. The company pays for the occasional bit of computer equipment. “It’s for managing the portfolio!” This is depreciated over three years, so basically we get a laptop every three years.

We could probably expense the Financial Times subscription and our mobile phones, but we don’t.

I once tried to persuade the accountant that the FIC should pay from my MBA, but failed.

Can I expense my accountant’s bill for my personal tax return to the FIC?

No. I guess you could come to an ‘understanding’ with your accountant. One where they overcharge you for FIC work and under-charge you for your personal stuff. But I don’t have that kind of accountant.

Do you hold UK REITS in the FIC?

No. This could be quite a good idea, because the FIC should receive the Property Income Distributions (PID) gross. Although PIDs are taxable.

It might work if we have sufficient expenses. However Interactive Brokers don’t pay the PIDs gross, regardless of what the tax rules say.

Attempting to reclaim them from HMRC is theoretically possible, and something my accountant would be delighted to help me with – at a cost.

We don’t really have enough tax-capacity to make this worthwhile.

Can you have direct properties (buy-to-lets) in the FIC?

Actually, yes! We have one, un-mortgaged, rental property in the FIC. We sold it to the FIC in early 2016. Just before the extra stamp duty for companies came in.

The income from the property is, of course, taxable, but it is tiny. We run enough general ‘management’ expenses to offset the income.

I have thought about moving one of my other buy-to-let properties into the FIC, but I’ve not been able to make it make sense.

To be honest if I’m going to sell it – with all the (personal) tax and hassle – I’d rather sell it to some other mug.

Do you have any other assets in the Family Investment Company?

We once did quite a bit of peer-to-peer lending. You know the sort of thing: Lendy, Archover, Funding ’Secure’.

At least it provided us with a deep well of tax-deductible write-offs.

Could I just use the FIC for all my shares?

You could, but it would likely be a bad idea, especially now that the indexation allowance has gone.

Your minimum tax rate on capital gains is 19% (rising to 25%) – and it could be as high as 54.51%. (The company pays 25% tax on gains, then you pay 39.25% on the dividend to you. That’s: 100 -> 75 -> 54.51%).

You’re much better off just holding those assets in your own name and paying 20% CGT.

This all sounds like a great deal of work. Is it?

I spend less time administering the FIC every year than I spent writing this article.

The ongoing obligations are:

- File a ‘confirmation’ statement with Companies House every year. (Takes five minutes. It’s nearly always the same as last year’s).

- File accounts with Companies House every year. (The accountant does it).

- Prepping the information for the accountant and checking their work takes about as long as it does to do our (again, fairly complicated) personal tax returns.

- Filing a tax return with HMRC. (Again, the accountant does it).

- There’s a bit of other admin, like renewing your Legal Entity Identifier periodically. (Interactive Brokers does that for us.)

How much does it cost to run?

It costs us about £2,500 per year. This is almost all accountants’ fees.

I know, I know, it should be less than that.

The costs are proportional to the nature and volume of transactions. But they are essentially fixed with respect to the size of your balance sheet.

(That said, I suspect an accountant would charge the £10m company a bit more than a £1m company, even if they did the same amount of activity).

How much do I need to put in to make this worthwhile?

Well, you know the costs now . You do the maths. Maybe £1m, if you’re starting from scratch?

It might be less if you’re using an existing company, or setting up a FIC that has a relationship with your trading company. I’ve never done this though. Once again, seek professional advice.

Can you recommend your accountant to help me set up a similar arrangement?

No.

Does this cause a problem with your employer?

Potentially. My employment contract explicitly forbids me from owning more than some percentage of a company, or being a director of another company, without my employers ‘written permission’.

The key here is to ask for the ‘written permission’ in good time.

I simply asked, by email, for them to confirm there was no problem with the arrangement in the same email I accepted their job offer. I have done this four times now and it’s never been a problem.

This sort of arrangement is a lot more common than you might think. Human Resources have seen it all.

In jobs where I was subject to compliance ‘personal account dealing’ rules, the FIC was obviously subject to the same rules.

Again, never a problem, if you follow the rules.

While we are talking about transparency…

Anyone can go to Companies House, click ‘Search the Register’, put in your name, find the company you are a director of, and look at the accounts.

There is nothing you can do about this. If this is going to cause you embarrassment, then a FIC probably isn’t for you.

Can I pay pension contributions for directors?

Yes, you can, but I’m not sure why you would?

These are ‘employer’ contributions that are made gross to the scheme – and are a tax-deductible expense for the FIC. You’re saving the company 19/25% corporate tax on the contributions, but you’ll pay anything from 15%-55% on withdrawals (from tax-free amount and basic rate all the way up to the LTA charge). So is there any point?

Again, this is a deferral of tax liability, more than an avoidance. It might be worth considering if the FIC is otherwise becoming liable for corporate tax and ‘needs’ some expenses, and if you have directors who are unlikely to get to the LTA and will be basic-rate tax payers in retirement.

But, again, if you’re rich enough to make this structure worthwhile, you probably don’t have those people in mind.

Can I pay salaries to the family members instead of dividends?

Yes. You could make the kids (once they are adults) directors and pay them a salary – although there’s quite a bit of paperwork involved with having employees that I could do without to be honest.

The advantage over dividends is obviously that their salaries are tax-deductible for the FIC – and you’re just using their nil-rate allowance. (I’m assuming you’re only doing this while they are students, basically).

Into the weeds

Can the company pay interest on the director’s loan?

I believe so, but you do have to do some withholding / filing with HMRC. It’s a bit of a pain – and, again, why would you do this? Presumably the last thing the director wants is taxable income?

Can I convert a regular trading company into a FIC?

I get this question quite a bit.

The classic case is the 1990s/2000s City IT contractor type who contracted through a pre-IR35 personal service company. They now have a few hundred grand sitting in their limited company and don’t want to pay dividend tax to get it out.

Be very careful here. There are some reliefs associated with being a proper ‘trading’ company that you may jeopardise.

This, as with every other word in this article, is something you should take proper professional advice on.

How does a FIC compare to some sort of ‘offshore’ arrangement?

I have a high level of confidence that the FIC structure is 100% above board and has zero retroactive compliance risk from HMRC.

This does not mean that the rules won’t change to make some aspect of it not ‘work’ any more.

The only thing I’m confident about with offshore arrangements is that they are expensive to set up.

In any event, it’s not trivial. You can’t just set your FIC up in the Caymans and pay no tax. HMRC will treat any company that is ‘controlled’ from the UK as if it were UK domiciled and tax it accordingly.

I do know people with offshore companies that they don’t ‘control’ – but are controlled by a chain of shadowy proxy entities that they also don’t ‘control’.

I am sure this is all completely legit, the way they’ve done it. But I also don’t have the sort of money that makes this level of risk or complexity worthwhile.

Is a FIC a ‘close company’ and does this matter?

Yes, most likely your FIC will be a close company. There are a few anti-avoidance measures that target close companies specifically – for example, targeting manoeuvres such as you moving abroad for a year and paying yourself a big fat dividend.

Unless you’re trying to use those avoidance methods, being a close company shouldn’t really make much difference.

There have been different tax rules for close companies in the past. This is certainly a potential vector for the government if they wanted to attack this sort of structure.

Is there anything you haven’t mentioned?

Yes – there are a few other tricks that I don’t want to discuss openly on the internet!

Thanks to Foxy Michael, who met Finumus on Twitter and was kind enough to review this article for gross falsehoods. If this Family Investment Company FAQ has whetted your appetite, visit his site. You can also read more from Finumus in his archive, or follow him on Twitter.