I hope you’re enjoying these good times as an investor. 2017 was another pain-free 12 months for our Slow & Steady passive portfolio. We ended 9% up on the year.

Coming in the wake of that monster 25% bunk-up in 2016, checking the numbers all year was a soothing ego-balm – about as mentally challenging as telling your mum you got a promotion, or handing over a Christmas present to a child.

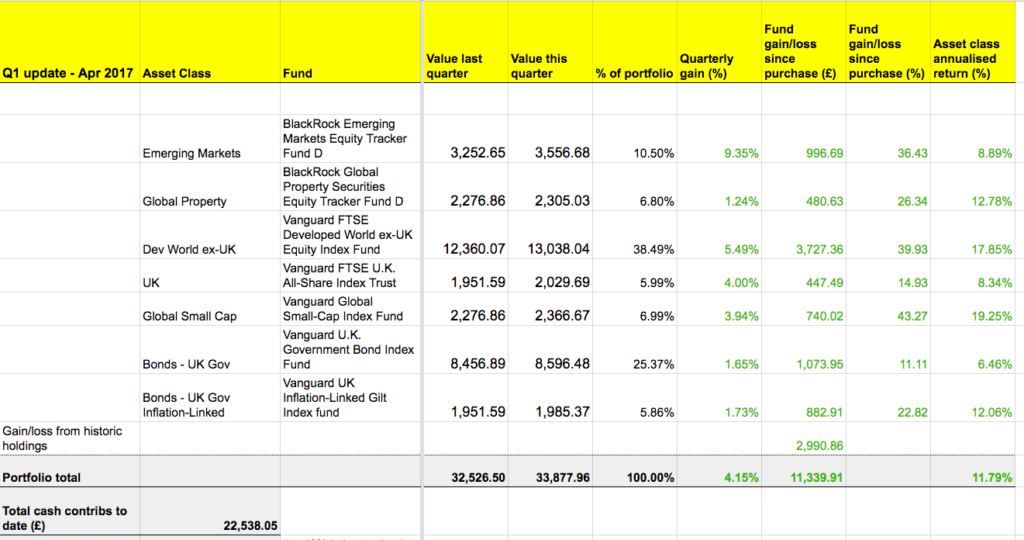

The bulls have owned the global stock markets like the streets of Pamplona. It was the kind of year that makes us all look like investing geniuses, as the portfolio numbers below show (brought to you by G-Whiz spreadsheet-o-vision):

- The portfolio is up 52% since we started seven years ago.

- That’s 10.92% annualised, or around 8.5% in real 1 terms. The historic real return of an equity portfolio hovers right around the 5% mark, so we’re living through a blessed time, believe it or not. (All the more so as we’re laden with sluggish bonds, too.)

- Emerging Markets was the star performer: up 21% this year.

- The FTSE All Share contributed 13.35%, with the FTSE 100 global behemoths larging it up on a weak pound.

- Our biggest holding – the Developed World ex-UK – brought in a similarly welcome 11.39%, with Europe and Japan scoring a rare victory over the US (which nevertheless hit new highs during the year).

With equities looking flush, it’s no surprise that our annual bond gains pale by comparison:

- UK inflation-linked bonds – 2.24% higher.

- UK Government bonds (conventional gilts) – up 1.64%.

These are nominal returns. Our fixed income assets have actually lost value after inflation.

The Slow and Steady portfolio is Monevator’s model passive investing portfolio. It was set up at the start of 2011 with £3,000 and an extra £935 is invested every quarter into a diversified set of index funds, tilted towards equities. You can read the origin story and catch up on all the previous passive portfolio posts.

But we should never get hung up on recent performance. Our longer term returns tell a slightly different story. Over seven years:

- The Developed World is the clear leader, up a staggering 15.5% annualised.

- Emerging Markets delivered near 10% annualised, but at the cost of some fearsome volatility along the way.

- We’ve only owned Global Small Cap for the last three years but it’s brought home a handsome 16.82% annualised.

- Global property has brought in 9% annualised over three years; it failed to keep pace with inflation with an insipid 2% this last year.

- Conventional government bonds have delivered 5% annualised over the full period – so around 2% to 2.5% ahead of inflation. A good performance by historical standards.

We’ve had a great run, with the portfolio working like the textbook example it’s meant to be:

- Equities are powering up our wealth.

- Government bonds are a handy diversifier, but they’re lagging over the longer term.

- Emerging Markets are hugely volatile and often diverge from the Developed World.

- The US market shows that a single market can trounce all-comers for a decade or more. As we can’t predict which market will win, we stay diversified.

Portfolio maintenance

It’s portfolio MOT time! With every stock market around the world steaming ahead, it’s an auspicious moment to reduce our exposure by moving 2% of our wealth away from equities and into government bonds.

We’re not doing this on a whim, though. We’re simply following the risk management tactic we committed to when we set up the portfolio, redeploying into less volatile bonds in 2% steps every year.

With 13-years left on this model portfolio’s investing clock, we’re now 66/34 in equities versus bonds. The plan is for our allocation to be 40/60 equities versus bonds by the end. We should be well insulated from a sudden stock market crash by that point.

As it is, the US market is richly valued, so I’m more than happy to snip back the Developed World fund by 2% (it’s over 50% invested in the US). That 2% shifts into the UK Government Bond fund. We’ll likely be very glad about that should markets dive in 2018.

We could have made marginal cuts to our other equity positions instead – Global Small Cap, Emerging Markets, the UK’s FTSE All-Share or Global Property – but we left them alone to maintain a healthy level of diversification across asset classes.

Our 2% asset allocation shift also merges into our annual rebalancing move. Every year we rebalance the portfolio back to its preset target asset allocation. Again this is about risk management, as we cream off the profits from assets that have soared in value and plough the proceeds into cheaper markets whose time should come again.

This quarter it means selling a chunk of Emerging Markets and Developed World and scooping up UK Government Bonds and a few Inflation-Linked Bonds in exchange.

Remember, we’re not making a judgement call. We’re just staying in line with the asset allocation we have set.

Increasing our quarterly savings

Now to deal with inflation. The sharp-toothed money nibbler has bitten off 3.9% this year according to the latest Office for National Statistics’ RPI inflation report.

To maintain the value of our contributions, we must therefore ‘inflate’ our own quarterly investments from £900 in 2017 pounds to £935 in 2018 wonga.

We’ll do that every quarter in 2018, although we’re only putting in £931.73 this time. Why? Because the rebalancing rejiggery equals a £3.27 contribution to Global Small Cap. That’s under our platform’s £50 minimum investment limit, so we’ve written it off for the sake of convenience.

Here’s this quarter’s buy and sell:

UK equity

Vanguard FTSE UK All-Share Index Trust – OCF 0.08%

Fund identifier: GB00B3X7QG63

Rebalancing sale: £20.78

Sell 0.102 units @ £203.88

Target allocation: 6%

Developed world ex-UK equities

Vanguard FTSE Developed World ex-UK Equity Index Fund – OCF 0.15%

Fund identifier: GB00B59G4Q73

Rebalancing sale: £881.44

Sell 2.674 units @ £329.60

Target allocation: 36%

Global small cap equities

Vanguard Global Small-Cap Index Fund – OCF 0.38%

Fund identifier: IE00B3X1NT05

New purchase: £0 (Leaves fund pretty much bang on 7% target allocation)

Target allocation: 7%

Emerging market equities

iShares Emerging Markets Equity Index Fund D – OCF 0.25%

Fund identifier: GB00B84DY642

Rebalancing sale: £285.94

Sell 175.964 units @ £1.63

Target allocation: 10%

Global property

iShares Global Property Securities Equity Index Fund D – OCF 0.21%

Fund identifier: GB00B5BFJG71

New purchase: £245.78

Buy 124.697 units @ £1.97

Target allocation: 7%

UK gilts

Vanguard UK Government Bond Index – OCF 0.15%

Fund identifier: IE00B1S75374

New purchase: £1674.16

Buy 10.28 units @ £162.86

Target allocation: 28%

UK index-linked gilts

Vanguard UK Inflation-Linked Gilt Index Fund – OCF 0.15%

Fund identifier: GB00B45Q9038

New purchase: £199.95

Buy 1.059 units @ £188.79

Target allocation: 6%

New investment = £931.73

Trading cost = £0

Platform fee = 0.25% per annum.

This model portfolio is notionally held with Charles Stanley Direct. You can use that company’s monthly investment option to invest from £50 per fund. Just cancel the option after you’ve traded if you don’t want to make the same investment next month.

Take a look at our online broker table or tool for other good platform options. Look at flat fee brokers if your ISA portfolio is worth substantially more than £25,000. The Slow & Steady portfolio is now worth over £38,000 but the fee saving isn’t yet juicy enough for us to push the button on the move yet.

Average portfolio OCF = 0.17%

If all this seems too much like hard work then you can buy a diversified portfolio using an all-in-one fund such as Vanguard’s LifeStrategy series.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

- That is, after-inflation[↩]

Comments on this entry are closed.

I’ve always been weak on maths.

“The portfolio is up 52% since we started seven years ago.

That’s 10.92% annualised…”

How can a 52% increase be 10.9% annualised over 7 years? I’d be really interested to see the maths, compound interest has always eluded me.

Happy new year!

Thanks @TA for providing this update.

A bit I didn’t follow….Up 52%, that’s 10.92% annualised.

I make it 6.2%. Since 1.52^(1/7) = 1.06164. Is there a typo somewhere?

Great news. I really like the strategy and thinking that you have adopted. I came across your approach in 2012, prior to this I dabbled too much and in hindsight without sufficient rigour to my approach. I am slightly ahead of you in glidepath (50/50) and going to hold this position until deaccumulation, then slowly glide up to mitigate sequence of return risk. Your references on this were excellent, so thanks!!

Here’s to a solid investing strategy in 2018 – whatever the market may bring☺

@Stu and others — I had the same thought when I edited and posted live (I’m on holiday on a super weak Internet connection) but put it up as I have a feeling this has come up before and @TA has an answer (from memory it’s to do with sequence of returns and the addition of new money.)

I agree that a vanilla 7-year compounded run that turned £100 into £152 with no new money would equal a much lower return rate — I make it around 6.2%.

Anyway, have asked @TA to clarify when he gets a chance.

(It’s also possibly a typo, in which case blame me! 🙂 )

@Stu @Brown Owl, once you factor in that additional contributions have been added the whole time it makes the number much harder to calculate, and means the annualised number does not reflect the current total increase. The 52% is the difference between current value and total contributions. The 10.92% is the increase of the value at the time, which did not include future contributions. I won’t do the full calculation as I don’t have an accurate breakdown, but suffice to say it looks in the ballpark of correct to me

Its the unitised returns thing isn’t it? You have to work out the unitised return each month or so – they take into account new deposits, and when you’ve got all that you can just sum and divide as I recall? I incorporated it into my spreadsheets after some useful tutorials given here..

Would using something like XIRR (as espoused by RIT) with all the dates and contributions give a different return figure?

Ah, yes – I bet it’s unitised returns – not all the investment has been earning for the full seven years (of course). I’ll go back and read that article again!

Thanks all.

I’ve decided to follow something similar for a new sipp i’m going to open – i’m using the theory that i’ll be able to have lower fees in my sipp than my workplace pension – all employer conts so still the same amount will be going in to pension.

Starting out at £160pm and thinking of starting with a 90/10 split with a 30 yr time horizon taking me near 63 – not sure i’ll retire early yet. Looking at:

10% UK bonds/gilts

25% UK (15% equity, 5%small cap, 5% value) – UK heavy but it’s the market in know best and i’ll live and retire here so seems to make sense to me

15% emerging markets – 30yrs seems to suggest i can take a higher risk level now

50 World ex uk (30% equity, 10% small cap, 10% value)

Thinking about leaving split as above for fist 10 years then final 20 reduce to a 50/50 split by first reducing small cap/value/emerging to reduce risk levels. Hopefully my logic ins’t too flawed!

This is really interesting, as I’m approach the point of stopping investing and starting withdrawing.

I’ve been passively index tracking for the last 20 years on equities on a 60/40 ratio, but my fixed income portion has been in a sequence of fixed rate cash bonds not “bond index trackers” – I’ve been pondering this as I’m finding the bond market hard to understand, and your article makes my confusion worse – as the return you are getting is worse than I get from cash (1-3 year fixed cash bonds) – so although the bond risk is low it is higher than cash, the return seems lower and the costs (although low with Vanguard) are higher (they are Zero for cash)….I’m finding it very hard to find a resource to tell me how to judge If I should move my cash into bonds..Given I anticipate a slowly increasing interest rate over the next few years…is there any simple information of Bond Vs Cash Vs inflation out there?

Cheers

Great to see the slow and steady portfolio chugging away. Having got into investing around 3 years ago, after visiting Monevator, the investment choice for moi are the Vanguard LifeStrategy funds. Keep up the fantastic work!

HTSC

@ Nick – nothing wrong with your logic assuming you can live with the volatility when equities slump.

@ Kev Black – I can’t think of any neat summary to point you to. I hear you though. The expected return on 10-year bonds is its interest rate. I can do better in cash up to a point. So I personally hold a fair bit of cash on the defensive side. However, where bonds really show their worth is in their negative correlation with equities in a downturn i.e. as equities fall, bonds can rise (not guaranteed, doesn’t always happen, but often does). Hence the blow to your portfolio is cushioned, you’re less likely to lose sleep etc. Cash doesn’t have that quality.

@ Gary & HowTo – glad to hear all is going well for you!

Me again. Re: the annualised return calculation. It’s XIRR. In other words, it’s money-weighted.

Unitised returns (which I don’t use) are time-weighted. i.e. all time periods are weighted equally, irrespective of how much money is invested when. It attempts to eliminate the effect of cash flows into or out of the portfolio. It’s the method used by mutual funds when preparing their published performance reports

A money-weighted return does not attempt to eliminate the effect of contributions and withdrawals: on the contrary, it specifically adjusts for them. Time periods in which more money is invested have more of an impact on the overall return than equivalent time periods in which less money is invested. For this reason it can differ substantially from the time-weighted rate of return when large cash flows occur during volatile periods.

Briefly on annualised returns. Moneychimp explains it very well:

A problem with talking about average investment returns is that there is real ambiguity about what people mean by “average”. For example, if you had an investment that went up 100% one year and then came down 50% the next, you certainly wouldn’t say that you had an average return of 25% = (100% – 50%)/2, because your principal is back where it started: your real annualized gain is zero.

In this example, the 25% is the simple average, or “arithmetic mean”. The zero percent that you really got is the “geometric mean”, also called the “annualized return”, or the “CAGR” for Compound Annual Growth Rate.

Volatile investments are frequently stated in terms of the simple average, rather than the CAGR that you actually get. (Bad news: the CAGR is smaller.)

http://moneychimp.com/features/market_cagr.htm

Cowboy is right the 52% figure is just the increase in current portfolio value versus the money contributed.

Interesting reading. I appreciate this has been going for 7 years now, but for those of us new to all this, how would you recommend getting started with something similar. A lot of the getting started articles are a couple of years old.

If you were starting this again, would you opt for a similar bundle of investments, or would you just go for something like Vanguard LifeStrategy?

I’d be interested to see how the Slow & Steady compares to putting the same amount of cash and time period into Vanguard Lifestrategy Fund, say 60/40, as to whether it’s worth the time and effort.

@ Phil

Personally I would avoid the Lifestrategy due to its bias towards the UK (nearly 25%) and simplify things further for your equity allocation with the Vanguard FTSE Global All Cap fund as it holds small caps and emerging markets as well, avoid the needs for separate funds. The only downside is you have to re-balance your bond allocations yourself whereas the Lifestrategy funds will do that for you.

I find the slow and steady portfolio updates very useful as a barometer for my own portfolio. I don’t have bonds/property in my portfolio, so I have higher returns with greater/more exciting volatility. It’s nice to have a comparison with passive investment as it mean I can ask myself if I am doing the right thing (for me), or if I’d be better off with a simpler, passive portfolio such as the one above.

@Nick

Quite a few people head this way asking for advice with their asset allocation. It’s difficult for people to comment fairly because no one knows you appetite for risk/volatility. There are studies that show most people don’t risk enough in early years. 30 years is a long time frame. a 50% stock market crash this year would not be noticed in anything other than a positive way when you look back at your portfolio in 30 years time. So 90/10 looks fine.

I set up a very similar portfolio myself 12 months ago. I have been using yours as a guide which has been a great help and have now decided to rebalance my own books but am struggling to get my head round the rebalancing aspect of it, essentially calculating how much I need to sell and redistribute to retain my 6% of this and 10% of that etc, is there a formula? I don’t want to just make the difference up by just adding funds where needed as it will work out too expensive so will need to sell and move stuff around like you have done (I don’t want to be tinkering too often apart from my contributions so the yearly schedule suits me perfectly). Is there any earlier posts or information detailing how you work out the maths of it all? I have had a look back through the blog but am struggling to find any explanations. I am new to investing so apologies if the query seem a little simplistic. Once it clicks its fine but until then its lots of head scratching!!

@ Komo – If you multiply your total portfolio value by the desired percentage then compare that to the actual value of that fund the difference would be what you need to either buy or sell.

eg. Allocation targets UK equity 50%, Global equity 50%. UK £600, Global £400 – total £1000

UK – £1000 * 0.5 = £500. £600 – £500 = £100 to sell. In this rather simple example to would easily extend to the need to by £100 Global.

Sorry if i’ve over simplified the example but i’m well aware im rubbish at explaining things and my usual technique of saying the same thing again isn’t that helpful.

@Phil If you’re new to the whole investment business, I’d suggest just getting on the wagon first, keeping things very simple, here’s an old post from Monevator talking about just starting instead of umming and arring about what to do: http://monevator.com/weekend-reading-little-things-matter-less-than-getting-started/

To get off the ground, a simple list of to dos would be:

– Choose a broker (using the broker comparison table)

– Decide on how much risk/excitement you can handle

– Choose a Vanguard LifeStrategy fund

A LifeStrategy fund will get you started, then if you decide you want a DIY selection of index funds, then sell LS units and buy what you want. Choosing a platform with no dealing fees for funds might be wise to start with, if you think you’ll chop and change funds.

Is it just me or does the performance of inflation-linked gilts seem completely crazy?

@ Nick – That was just the trigger to get the neurons firing I was looking for! I actually added my latest contribution to the total portfolio value then divided my target percentage holdings for each fund from that and compared it to the actual fund value as of today and hey presto I got my answers. Thanks for your help Nick, so simple when you know where you are looking… Just got to remember this come next January!!

Just had another read through and noticed the fund choice are quite Vanguard heavy, even where there appears to be slightly cheaper alternatives. Is the a reason for this? Is Vanguard one of the better passive providers or have prices lowered but not by enough to switch?

@ Nick – right on both counts. It’s not worth shifting for the odd 0.01% here and there and when I check Vanguard’s tracking difference versus rivals, they often hug the benchmark more closely than rivals, so fewer hidden costs.

@ Phil – I think the decision to delegate everything to a LifeStrategy fund versus a more personalised portfolio comes down to temperament. If you like the idea of optimising, being hands on and expanding your investing knowledge then a personalised portfolio makes sense. But if investing is a big turn off and you’d rather automate it then it’s LifeStrategy all the way. There are a few reasons why you might expect to do marginally better with a personalised portfolio over the long term but they’re not guaranteed and rely on sticking to the plan. Far from easy!

I’ve been a passive investor for 30 years and now I’m at the point of wanting to press the ejection button and live my independent life. Thats pretty scary (hence the question on cash Vs bonds earlier).

This may not be allowed, and if it is not my apologies.. But I don’t think I’m asking for financial advice as I’m using a figure “X” and what I consider X to acually be and whether or not it’s a good number is down to me.

But I believe the below follows the logic ( and principles ) of passive and keep it simple investing.

I’m an interested in opinions as to whether the below is consistent and correct ( mathematically) and following our principles….any views?

It’s interesting when you need to change from putting money in to taking it out, it’s a real hard thing!

My risk tolerance is pretty good, I believe in the long term equities always recover but am basing this on having a pension acting as my cushion.

So

Where I am today….about to tell the boss “cheerio”

Outgoings:

Basic need £x after tax (not penury, a reasonable life)

Desired need £1.5x after tax (a nice flexible life)

Capital:

Set aside £7.5x Invested but to spend over next 10 years on Kids

POT £32.5x to generate income (and to leave any remains as estate)

Income:

Pension £x before tax, also inflation linked to a max of 5%

Required income from pot for desired need:

£0.5x after tax

£0.75x before tax (on the safe side – I am maximising ISA use)

(Don’t decrement need as we get older – either cover for health and care or upside for inheritance.)

Withdrawal rate = 2.3%

So Annual POT real value = POT – 2.3% -inflation +investment return

Investment approach:

Pension close to providing basic need, so leave an aggressive 60/40 Equity/income split.

Target to average Inflation+1 over the long term.

(Potential to withdraw less when markets/times get hard.)

Duration if approach meets target (inflation +1).

Real time decrease in POT value of 1.3% = 75 years before exhausted

Potential lifespan: 40 years (If we’re very lucky!!)

Minimum investment return to hit that: Inflation

POT/set aside asset classes %

UK all share tracker 30

Euro ex UK tracker 15

RoW ex Euro tracker 15

UK corp bond tracker 10

UK govt bond tracker 15

Property 7.5

Cash 7.5

@ Kev Black

So your basic need X is covered by a pension, and you need take only 2.3% from your other capital to give 0.5 X (net of tax) to provide desired needs.

0.75 X pre tax implies 33% tax which seems high given you have some in ISA’s, and then you have tax free personal and dividend allowances before the 20%, 40% and 45% tax bands. On the other hand what tax will be paid on your pension (X before tax).

2.3% is a very low withdrawal rate. Wade Pfau has suggested that safe withdrawal rates should now be below 4%. The RIT blogger is looking at a withdrawal rate of around 2.5%

I think 60/40 is over-cautious rather than aggressive. I prefer a natural yield approach from equities and would look for a portfolio yield close to the FTSE All Share yield of 3.6% with a withdrawal rate below that.

Interestingly 40% in UK 10 year gilts at 1.32% and 60% in the FTSE All Share at 3.6% would give an income of 2.7% overall which exceeds your requirements.

@ Kev Black

Also, back in October there was discussion here of a 1.9% safe withdrawal rate. My comment is number 16.

http://monevator.com/weekend-reading-kensington-vs-ebbw-vale/

@David M

Thanks. Yes the asset allocation has some kind of intent to in theory allow me to only need to live on yield, and allow capital growth to deal with inflation.

I also agree (which is kind of why it’s scary) that it’s all theory. Clearly in retirement I need what I need not precisely X (in real terms) every year. I also would expect to hunker down if we were in a bad patch.

I agree the tax position I’ve placed is conservative, but that’s upside…clearly my pension uses up tax allowance, but as you say I am over stating tax…

You comment on not actually aggressive is interesting me as I have been thinking that too. If I consider my POT as needing to provide only 1/3 of my income then actually my total income is 80% pension/bonds/property/cash and only 20% equities, which is not aggressive. So I am now wondering whether to move into equities a little more….but given I am no longer investing, I need to ponder on the big unknowable – how will I react to the next down turn when things are dropping but I’m not able to buy at the lower prices…..I wish I knew – may be I’ll edge equities up a bit, but not too much more….70/30 rebalancing from bonds….

Hi,

I’ve been reading the articles on this website for a while now and am very much aligned with the passive approach to investing.

One thing I have been thinking about is what to do with emergency cash whilst I am still in the early stages of accumulating. I think it would be sensible to keep 3/4 months of expenses in liquidity in case of unexpected issues. Whilst on the one hand I’d be inclined to keep this in cash in the best savings account I could find, I’m also drawn to the idea of investing it on a lower risk basis. For example, maybe it could be invested into a vanguard 20/80 life strategy (equities/bonds). To my mind there is a moderate possibility of growth above inflation (which would be nice) and the risk of capital depreciation should be relatively low given the heavy bond weighting. As it would be emergency funds I wouldn’t want to risk the value reducing by 50%, but I’d probably be willing to accept a risk of it dropping down to 85/90%. Am I missing an obvious risk factor here somewhere?

Would be really interested to hear other people’s thoughts on this and what they do with their “emergency funds”.

Keep up the great work all.

Seb

@ Kev – your passive investing principles seem sound. The property section of your portfolio is rental property you own? It’s not a REIT tracker I take it? I’d argue your portfolio is a little more aggressive than it first appears as corporate bonds don’t belong in your defensive, fixed income allocation. They’re most likely to go down in a crisis rather than act as a safe haven, so should be lumped with equities. I’d personally be very comfortable hitting the eject button on a 2.3% withdrawal rate, so congratulations!

Take a look at this book too, you may find it useful:

http://monevator.com/review-living-off-your-money-by-michael-mcclung

@ Seb – I don’t like the idea of investing emergency funds because your emergency is quite likely to show up during a recession or financial crisis. In those circumstances, equities and bonds could drop together and significantly reduce the value of your fund when you need it most. Or perhaps you lose your job in the next year or two and the bonds have taken a fair old hit due to a sudden rise in interest rates. They’ll make it up eventually but only if you stay invested. Without actually checking, I suspect the LifeStrategy bond allocation has a reasonably long average duration – let’s say 11 or 12. So, if my estimate is about right, your bonds take an approx 11 – 12% hit for every 1% rise in market interest rates. It’s horse for courses. Cash is the best asset for emergencies because it’s stable and liquid. Maybe you could get an extra percentage point of growth somewhere else, but that might be cold comfort if you get unlucky during a real emergency.

@The Accumulator, Thanks

Yep the Property is my wife’s old house which we rent out.

Interesting point on Corp bonds.

I’ve slightly revised my allocation based on feedback here….which is helpful in terms of making me think….

UK all share tracker 30 (mix of Vanguard, L&G, M&G so to not be totally exposed to V)

Euro ex UK tracker 12.5 (Vanguard)

RoW ex UK tracker 22.5 (Vanguard)

UK corp bond tracker 7.5 (Vanguard)

UK govt bond tracker 15 (Vanguard)

Property 7.5 (a house!)

Cash 7.5 (half in 1 yr bond, half “easy access”)

Really appreciate the thoughts. Now I have to screw up the courage and stop working!

Thanks very much Accumulator for your comprehensive response. Your approach makes sense to me. I think I probably need to get a better understanding of bonds and the economic forces that affect them. In any case, I think I would probably avoid investing emergency funds now. Thanks very much for your help.

Seb

One thing to be aware of with passive investing is which flavor of the index you are comparing against. Often, funds are benchmarked against a price index which ignores dividends. For the most appropriate comparison of performance and tracking error you need to use the Total Return (TR) version of the indexes.

Maybe this is something the monevator could cover in a future post?

Love these passive investing posts, BTW. I can tell you from first-hand experience you are right on the money.

Regards,

Hi,

My question is about the continued heavy investment in Bonds. Surely if interest rates can only go one way over the coming months/years this will force the value of Bonds down. I understand the the value of having an uncorrelated mix but why not just hold cash instead of something that will almost certainly decrease in value as interest rates increase? What is it I am missing?

@Chris — In short, mostly because you (/we) don’t know what’s going to happen (nobody does) and “surely” is not a word to use in this context.

With that said, with government bond yields still so low, I think for private investors cash is a decent substitute for bonds. We’ve been through this a *lot* of times so forgive me for not going through it all again (and note that people were saying *exactly* what you have written here as far back as 2010. 🙂 )

I’d suggesting having a read of some of these, and the comments:

http://monevator.com/tag/bonds/

http://monevator.com/tag/cash/

Hi

You have iShares Global Property Securities Equity Index Fund D in your portfolio which has an OCF of 0.21% and another class H has OCF of 0.20%. I went for the later and looking at the performance tables, it looks like H class returns are marginally better. Is there any reason why you went for Class D 0.01% costlier for effectively the same thing or is it?

Hi, the H class is a platform exclusive (Hargreaves Lansdown from memory) whereas the D class is universally available so I felt more appropriate for a list like this i.e. most useful, to the most people. They are effectively the same thing.