The previous thrilling installment of our model portfolio saw us undertake some major asset allocation surgery – diversifying into global property, inflation retardant government bonds, and fruity small caps.

How has that worked out?

Well, none too shabbily. The property fund is up nearly 9% on the quarter, the small caps are up over 9% (outstripping our other equity holdings, as you might hope during good times) and even our index-linked bonds posted a 3.44% gain.

In fact every single asset has soared, with the rising dollar acting like a thermal under the wings of much of our overseas allocation. (As the dollar advances so does the value of our US assets).

Here’s the portfolio latest in glorious spreadsheet-o-vision:

This snapshot is a correction of the original. N.B. Glb Prop, Dev World, Small Cap and Inflation Linked bonds show year-to-date returns as holdings are less than one year old. (Click to make bigger).

It’s been an exceptionally benign quarter, as the tree rings of our portfolio show a growth spurt of over 6%.

That means our portfolio is up £4,800 and 31% from year zero.

The Slow & Steady portfolio is Monevator’s model passive investing portfolio. It was set up at the start of 2011 with £3,000 and an extra £870 is invested every quarter into a diversified set of index funds, heavily tilted towards equities. You can read the origin story and catch up on all the previous passive portfolio posts here.

Easy money

These are the times when it’s easy to be an investor – when everything you touch turns up trumps.

Just looking at the numbers releases feelgood juice. I can feel the indestructibility chemicals bathing my ego.

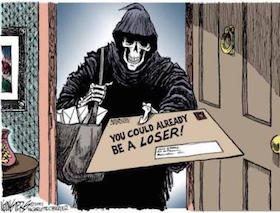

Which definitely makes this a good time to keep myself on edge by reading a doomster post or two about wildly overvalued markets.

Things have gone so well for so long that we’re in danger of losing touch with the feelings of loss and despair handed out by the market in 2008. It’s starting to feel like it happened to someone else.

Recently my mum inquired about how well her portfolio was doing. I was reluctant to say. I don’t want her to get used to the idea that equities only go up.

I try to think of it like some crazy game show. The money isn’t mine until I bank it. The earlier I bank it the less likely I am to hit the jackpot. Taking losses is as big a part of the game as enjoying the high rolls. Except losing is much more painful, so don’t overreach yourself.

Rebalancing is a good way to take a little risk off the table if you’ve been riding your luck for a while.

It’s worth mentioning that I don’t know how this new version of the Slow & Steady portfolio stacks up against the previous version. I make it my business not to know. The decision is made and there’s nothing more pointless than buyer’s remorse. I’m not going to torture myself with alternative histories.

Even if this new version has its nose in front then it may not stay there. And the difference will be slight.

In any case, there’s an infinite number of portfolios that are doing better and worse. I didn’t choose any of them.

This is the one I did choose and the underlying strategy is sound. That will do me.

In other news we’ve earned £12.99 in interest income from our UK Government bond fund. We celebrate by automatically reinvesting it back into our accumulation funds – adding a few extra ice crystals to our burgeoning snowball.

New transactions

Every quarter we sink another £870 into the market’s whirlpool. Our cash is divided between our seven funds according to our asset allocation.

We use Larry Swedroe’s 5/25 rule to trigger rebalancing moves, but all’s quiet this quarter. So we’re just topping up with new money as follows:

UK equity

Vanguard FTSE UK All-Share Index Trust – OCF 0.08%

Fund identifier: GB00B3X7QG63

New purchase: £87

Buy 0.537 units @ £162.04

Target allocation: 10%

Developed world ex-UK equities

Vanguard FTSE Developed World ex-UK Equity Index Fund – OCF 0.15%

Fund identifier: GB00B59G4Q73

New purchase: £330.60

Buy 1.424 units @ £232.15

Target allocation: 38%

Global small cap equities

Vanguard Global Small-Cap Index Fund – OCF 0.38%

Fund identifier: IE00B3X1NT05

New purchase: £60.90

Buy 0.311 units @ £195.99

Target allocation: 7%

Emerging market equities

BlackRock Emerging Markets Equity Tracker Fund D – OCF 0.27%

Fund identifier: GB00B84DY642

New purchase: £87

Buy 71.078 units @ £1.22

Target allocation: 10%

Global property

BlackRock Global Property Securities Equity Tracker Fund D – OCF 0.23%

Fund identifier: GB00B5BFJG71

New purchase: £60.90

Buy 37.202 units @ £1.64

Target allocation: 7%

UK gilts

Vanguard UK Government Bond Index – OCF 0.15%

Fund identifier: IE00B1S75374

New purchase: £121.80

Buy 0.824 units @ £147.79

Target allocation: 14%

UK index-linked gilts

Vanguard UK Inflation-Linked Gilt Index Fund – OCF 0.15%

Fund identifier: GB00B45Q9038

New purchase: £121.80

Buy 0.788 units @ £154.67

Target allocation: 14%

New investment = £870

Trading cost = £0

Platform fee = 0.25% per annum

This model portfolio is notionally held with Charles Stanley Direct. You can use its monthly investment option to invest from £50 per fund. Just cancel the option after you’ve traded if you don’t want to make the same investment next month.

Take a look at our online broker table for other good platform options. Look at flat fee brokers if your portfolio is worth substantially more than £20,000.

Average portfolio OCF = 0.18%

If all this seems too much like hard work then you can always buy a diversified portfolio using an all-in-one fund like Vanguard’s LifeStrategy series.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator