This thought-provoking guest post is by Andrew Henderson, the author of Nomad Capitalist.

Even when you have discovered the freedom of expat life, chances are that you will still need to process the transition.

It can feel a bit like a home-country detox.

This is more than just dealing with cultural shock. In many cases, you are learning to adopt an entirely new perspective and approach to life.

Living and traveling abroad has a way of changing the way you look at the world because you are suddenly exposed to a thousand different ways to do things that are done only one way at home.

It can be tempting to ask why something is done differently because what you know is all that you’re used to.

But when you detox yourself from the one-country, one-way-of-doing-things mindset, you will discover a world of possibilities full of better solutions, better lifestyles, and better options.

Investing is no exception to this rule.

Global potential

Learning to invest as an expat can change your entire investment strategy for the better. But only if you let it.

There are funds and companies in other countries that do things somewhat similar to what you’re used to, but as someone who has left my home country and fully given myself to investigating the entire spectrum of investment opportunities abroad, I know that there are better options.

In fact, there are so many options that it takes a bit more work to know which investments best fit into your personal strategy, especially compared to the ease of simply handing your money over to a mutual fund. If you’re not opposed to figuring that out, you can easily enjoy much higher returns.

Before deciding where and how to invest overseas, I find it helpful to ask the following four questions:

- How committed am I to continue investing in my home country?

- Where am I going?

- What options are available to me?

- How will my expat journey affect my views on investment and risk tolerance?

It is important to answer the first question because many investment options are only available to residents of certain countries.

For example, in the US you can invest in everything from mutual funds to LendingClub. These companies often have offices in Europe and accept customers from countries like the UK, Germany, Singapore, and Hong Kong.

However, they may not allow you to invest if you do not have resident status in those countries.

Because of this, your expat lifestyle may be limited if you want to continue investing in your home country.

In contrast, you will not limit your investment options if you choose to be an expat. As you ask yourself the four questions above, it becomes easier to realize that if you are able to live somewhere else, why not invest somewhere else as well?

I call this geographic diversification.

On the ground diversification

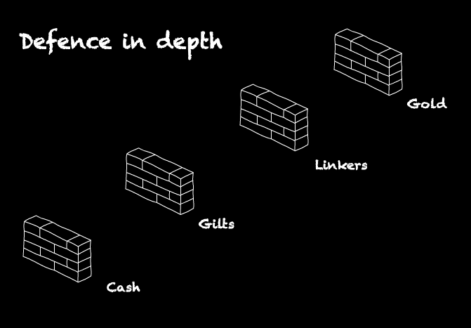

One of the basic principles of a strong investment portfolio is to avoid putting all of your eggs in the same basket.

If you wouldn’t invest all of your funds into one stock issued by a single company, why would you make all of your investments in a single country?

Not only can you spread your risk through geographic diversification, you can also increase your investment options.

In countries like the US, regulation from the SEC gets in the way of some of the best investment deals. In the UK, the market is so developed that people have to get creative to invest and find cash flow, especially in today’s low-yield environment where you can no longer make money just parking your cash in the bank.

As a result, people turn to investment deals like student housing rentals that may sound great upfront – invest £100,000 a year and get 9-11% back – but then how do you sell that? How do you sell one room in a student apartment in an area that would lose its value if there weren’t any students?

Rather than struggle to find creative options to get mediocre yields in your home country, why not simplify things and just look elsewhere… especially if you are an expat?

Living somewhere else allows you to see the flaws in how people invest where you are from – even the flaws in what you’ve been doing.

You’ll begin to see that many people invest where they do simply because they think that those are their only options. And if you are not comfortable investing anywhere but the UK, those just might be your only options.

Fear of doing anything beyond what is right in front of you can leave you choosing between an HSBC bank term deposit or a student housing development.

Fear keeps you from seeing the possibilities.

But those who have embraced the expat life have already shown that they are comfortable outside of their comfort zone.

So let’s look at the possibilities that open up when you look beyond your home country.

Georgia on my mind

To begin, I recently opened a US dollar bank deposit account in the country of Georgia and I am making 4.5% just by parking my cash there.

In countries like Cambodia, you can make 6% doing the same thing. And in other places, you can make even higher returns.

For instance, bank deposits in Armenia are currently about 10%. I ran a recent comparison over the last four-year period on the Armenian dram and the currency fluctuation was less than 1% against the US dollar.

Imagine that you were to put your money in at 10% interest in a foreign currency. Suppose you lost less than 1% converting to the new currency and less than 1% converting it back and you lost less than 1% against your base currency. You would be down roughly 2.5%.

However, after four years, you would get 40% interest (10% x 4 years) by simply putting your money in a foreign bank account.

If you want to invest in real estate, things get even better.

If you were to stay home in the UK, you would easily pay £15,000 or more per square meter for a property in the city center with a yield of 4.5% max.

In cities like Tbilisi, Georgia or Phnom Penh, Cambodia, you can buy property in the city center for $1,000 or less per meter and make much higher returns.

These properties may not be perfectly renovated, but they are in great locations and are as much as 1/25th the price you would pay in London, 1/20th of what you would pay in Singapore, and 1/15th the prices in New York.

That is dirt cheap when it comes to international real estate.

You can find these low prices and higher returns in numerous places around the world. Even Colombia has deals like this; you won’t find them in the capital city of Bogota, but because Colombia is a much bigger market, it is still a great investment.

Market timing

In many instances, timing is key.

For example, you won’t find these prices now, but in the summer of 2018 you could find properties for $1,400 per meter in Istanbul. At the time, the Turkish lira was crumbling and many people were just walking away. Properties that were normally $3,000 per meter went down to $1500 per meter and people started panic selling.

That was the time to jump in.

Turkey has strong fundamentals – including a large population that reproduces – which means that even if some of your rental income is in lira for a couple of years and the lira gets battered, you will eventually come out on top.

Some might see an investment like this as a risk, but my personal expat journey has shown me the difference between perceived risk and actual risk. People often question my wisdom for even recommending real estate investments in a place like Cambodia, but my investments there made over 20% ROI in the last year.

Don’t take this as personal financial advice, but try getting that in the US!

There are some properties in Australia and the UK that have had their total yield go down because they made 2% yield and their property price went down 5%.

I made 20% in Cambodia. I have had deals in Georgia that were in the double digits.

How much lower can these prices go for countries that are experiencing huge booms of tourists? Their markets are just starting to take off while developed countries like the UK leave investors scrambling for creative ways to make even a small return.

See the bigger picture

As an expat, if you can get over the fact that you’re investing in markets that you’re unfamiliar with, you can go back to the basics and buy core properties in amazing locations for low prices and wait while collecting some income.

Most people won’t do it because they are afraid. They think that the UK and the US are the only safe places in the world.

That is obviously not true.

Most people just don’t know how many possibilities are waiting for them out here in the rest of the world. Where I come from, many people have never left the United States. Almost 60% of Americans don’t even have a US passport, disqualifying themselves from international travel.

But as an expat you are already out in the world. You are different.

If you’ve been enjoying the expat life for a while now, you may have begun to notice the opportunities already. If you haven’t, just switch on your investment mindset wherever you go.

Good investments do not exist in a vacuum back home. For the globally-minded citizen, the best investments are just waiting to be found.

Andrew Henderson lives by five magic words: “go where you’re treated best”. The founder of Nomad Capitalist helps people to find the best places to live, bank, invest, incorporate, start a business, hire, date, and more. You can also read his book.

Andrew Henderson lives by five magic words: “go where you’re treated best”. The founder of Nomad Capitalist helps people to find the best places to live, bank, invest, incorporate, start a business, hire, date, and more. You can also read his book.