Note: This is a rant this week. Feel free to skip down to the money and investing links if it’s not your bag. I will delete abusive comments.

–––

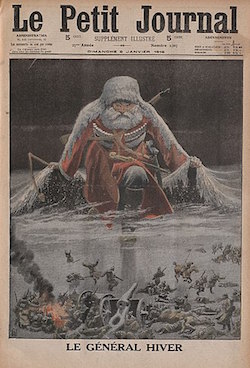

“I thought then, for the first time, about the arrival of General Winter. If he had been here ten days ago, he would not have been much help to the Args, dug in on the heights with no chance of their High Command getting their air forces into the skies. But I think he would’ve finished us.”

– Sandy Woodward, Admiral in the Falklands War

And so nationwide riots on the utterly predictable absence of Brexit on 31 October turned out to be another fantasy dreamed up by the nation’s Barry Blimps.

For which we should be grateful. But not surprised.

I think it’s becoming clear that many of those who voted Leave in 2016 don’t actually care much for Brexit. The polls show the country still fairly evenly split, true, but it defies credibility to imagine a million Leave supporters marching through London.

The EU was the sworn enemy of a minority of politicians, businessmen, and trade union leaders. For most of the rest of its British detractors it was a fantasy bogeyman – used by the tabloids to scare the credulous, but evaporating when exposed to the light.

With the exception of migration (which for the trillionth time we could have at least tightened using existing EU rules, without Brexit) few Leavers can point to any concrete downside caused by our membership.

It’s all about theoretical losses of sovereignty, or fears of a future super state.

You say tomato, I say turnip

How do we reconcile this practical disinterest with the anger that’s split the nation?

It’s clearly because even though many Leave voters don’t really care much about the EU, they understandably do care that their vote is apparently being denied.

Not enough to riot, thankfully, but enough to make their grown-up kids dread Christmas.

To help them get this angry, they’ve been aided and abetted by three years of pie-in-the-sky promises from Government, which gilt-edged the stretched version of reality peddled by the Leave campaign – and by a bucket load of dangerous posturing about ‘the enemies of the people’.

True, if you’ve spent more than five minutes following the saga you’ll know the real reason we’ve not Brexit-ed is because MPs have been trying to square Leave’s Pandora’s box of bogus promises with the realities of globalization, the Union, and the economy.

You’ll also know that as a result, both Remainer and Brexiteer MPs alike have voted down the various Withdrawal Bills.

But never the mind facts, eh? This is Brexit we’re talking about.

As for Remainers, we’re not just angry because we’re leaving this flawed but ultimately positive project.

We’re angry because Brexiteers’ means don’t justify the end – and because even now, nobody has been able to articulate why the end is worth it, anyway.

We’ve all taken our sides, and we’re more dug in and furious than before the Referendum ever happened.

Populism goes mass-market

I have a golden rule in life and as an investor: never presume things can’t get worse.

It’s very possible this General Election will double down on the division. You may be relieved to learn then that I don’t intend to follow the next six weeks of futility here on Monevator.1

I do get a few nice comments and emails saying our Brexit debate is better than elsewhere. A few Leavers have even generously said I’m more balanced than most of the opposition, which perhaps shows how bad things are.

But even if this was the right venue for relentless politics, my heart is not in it. Because this election seems doomed to achieve nothing except to make the environment more bitter.

Having alienated most of its thoughtful or at least moderate minds – some of whom resigned as MPs this week – the Conservative party under its professional blusterer-in-chief will stomp further to the right. A more right-wing Tory party will be a feature, not a bug.

Labour meanwhile is headed by one of the few people in Parliament who could make Boris Johnson look like a preferable Prime Minister.

Lastly, edging out towards the fringes as the main parties abandon the center, the Lib Dems, the SNP, and the Brexit fan club party are taking more extreme positions.

We saw the Rebel Alliance defeat a no-deal Brexit. Now we have the political equivalent of a Tatooine cantina vying for our votes – would-be MPs whose positions on Brexit are ever more alienating to the other side.

Division! Clear the lobbies!

While I think Johnson will probably get a small majority – leaving aside for now the Farage factor – I doubt he’ll get an obedient army of Brexit ultras under his command.

But even if he does, this season’s upcoming plot twist is premised on the idea that ‘sorting out Brexit’ will be the end of this farce.

In reality, the trade negotiations with the EU – technically termed ‘the hard part’ – will begin the day we leave. And even if we eventually bork out with a no-deal, once the lorry motorway car parks have been set-up and the Swiss have flown in emergency medical supplies we’ll soon be back to Brussels to start negotiating again anyway. Getting a deal with the EU is, well, non-negotiable.

Contrary to the Referendum marketing, our trade with Europe is of supreme importance. Some see BRINO2 as the endgame, given the desire of most MPs to avoid an economic hit.

Indeed as the years tick by, Brexit could seem an ever more Quixotic project with no upside and dwindling supporters as the older Leavers die and the younger ones start deleting their embarrassing pre-2020 social media accounts.

We might even end up back in the EU in a decade, only with all our special arrangements gone.

Remember, there is no upside to Brexit except maximizing technical sovereignty, which nobody will notice anyway, and, if you it appeals to you, potentially curbing migration, which the Government will probably try to offset with work visas and more ex-EU migration, for economic reasons.

Moderates won’t find emptied council houses for their kids. And racists won’t be relieved.

Meanwhile any sleight of hand Johnson and Javid do try to gee us up with by ending austerity could have done without Brexit – and with £100bn extra in the economy if growth hadn’t been flattened by years of Brexit buffoonery.

Lies, dammed lies, and Leaving

Much is said about how the millions of disenfranchised who voted Leave will feel betrayed if we don’t Brexit.

But what about if we Brexit and it achieves diddly-squat for them?

The harsh reality is most of these people were lost to politics before they were weaponized by Dominic Cummings’ data-targeting. You think the past three years has won them back?

They came in pissed off and that’s how they’ll stay, whatever happens from here.

Leave-supporters can bluster all the want, but Remainers have been right about nearly everything so far – except that immediate post-vote recession. We’ve had a slowdown, sure, but no recession.

But otherwise?

Leaving the EU turns out to be very hard, not very easy.

Far from superior trade deals on day one, we’re 1,226 days on from the EU Referendum and only about 8% of UK trade has even been ‘rolled over’ under existing EU trade terms.

There isn’t a grand emerging consensus that Brexit is an opportunity. There’s at best a grudging concession that we have to go through with it, a bit like a colonoscopy.

And the EU hasn’t fractured and bickered – it’s more united than ever.

We haven’t taken a new position on the global stage, except perhaps as the clown act.

The special Brexit Day fifty pence coins are being melted down but the ‘Get Ready For Brexit’ posters are still up, reminding us of £100m that we taxpayers will never see again – and that is only the thinnest end of the national waste of money, time, and effort.

Déjà vu (that’s French for Brexit)

Then again, we haven’t left yet, right?

That’s a fair retort, in that it’s at least true.

For those who don’t read the comments, this is what happens after every Brexit article here so far.

A fairly polite conversation takes place, in which initial claims of political infringement by the EU or an economic advantage from Brexit are efficiently taken apart. A stat will be thrown out stating that most Leave voters were motivated by sovereignty concerns, so why are we discussing the economy? Yet nobody will give good answers when probed about the actual impact of this perceived lack of sovereignty, or why Britain is especially affected. Eventually, Brexit supporters will say we don’t understand, it’s about migration, or ‘culture’ or ‘Englishness’. (It used to be I’d also get a few emails about Muslims, but at least that seems to have died down.)

Equally, I’m sure this rant feels like Groundhog Day to Leavers, too.

Perhaps it’s the one that will make you unsubscribe? A few always email me to say they’ve had enough, they’re off.

I don’t blame them – but I feel I can’t ignore the White Elephant in the room.

Around and around we go.

None of the above

Remember 2012, and the Olympics, and Britain on top of the world?

Remember 2015, and fancy skyscrapers popping up across London? Remember start-ups founded by clever migrants who came to the UK for our global outlook? Remember how we got through the financial crisis without huge job losses and remember talk of building a Northern Powerhouse before every plan was washed away by Brexit? Remember the Polish builder who fixed your boiler? Remember when you couldn’t get a coffee south of Watford without a sneer and then for ten years it was all smiles from young Spaniards and Greeks? Remember how you could daydream about living in Rome or Barcelona or Berlin because it was your right, not a gamble? Remember when the UK was the fastest-growing economy in the G7? Remember when Cameron was a nice-ish Conservative leader, modernizing the UK’s natural party of government?

Remember when we increasingly believed we were more alike than different?

And Leavers ask us to worry about the betrayal of voters who came out once to protest.

Many of us already feel betrayed.

See you on the other side.