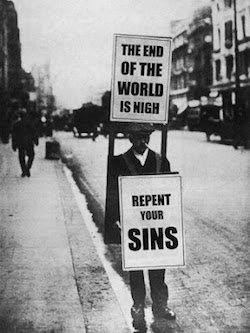

There’s nothing like a bear market to bring out the doomsters and hindsight heroes. Throw in a global pandemic, and it seems half the population is walking around with a sandwich board proclaiming the end of the world is nigh.

Actually, that does a disservice to the bloke on the High Street reading Revelations aloud.

At least your standard apocalyptic visionary stays in their lane. Many who claim stocks are toxic or that FIRE is finished were bull market cheerleaders a few short months ago. Some who argue airlines will be forever mothballed were warning ever more flying would cook the planet when this year began.

Don’t get me wrong. The pandemic is a threat to life and to share prices. The consequent economic shutdown is even worse for markets – and it’s not good for our long-term health, either – although with the data we’ve got you can see why Governments felt they had no choice but to try to curb the virus’s spread.

Time will tell. History must remember we were all groping in the dark.

The same is true of share prices.

It is easy to see why markets tanked at speed given we’ve driven the economy into the buffers. Massive monetary and fiscal support will not stop disruption or prevent profits turning to losses like the slumping A-Level grades of a nerd who discovers the dubious joys of a spliff while their school is shutdown.

But the pandemic will not last forever.

Holding back the years

Remember share prices reflect the best estimate of the value of a firm’s future earnings into perpetuity – discounted for uncertainty the further out you look.

Risks to the downside abound today. That ramps up the uncertainty discount.

At the same time we can be pretty sure that cash we thought would hit company bank accounts in March, April, and May will be much depleted.

Some firms will go bust. You can’t earn future returns if you’re bankrupt!

But for all we don’t know about it, we do know this coronavirus looks like a fairly typical upper respiratory tract infection that will run its course. Maybe we’ll get a vaccine, maybe it’ll burn itself out, or maybe it’ll become endemic and most of us will eventually get some resistance.

That’s hardly the end of the world.

In a couple of year’s time – maybe sooner – we’ll still be recovering from the economic impact, but we’re unlikely to still be glued to the virus statistics.

So what’s really changed – and what is just a reminder of what was always true?

Markets fluctuate

There’s nothing new about a bear market. You can see that crashes happen quite often if you stand back and take a wider view.

But shares still deliver good returns over the long-term.

The recent crash was extraordinarily speedy, but even that’s not novel.

As David Gardner, the co-founder of The Motley Fool, puts it:

“Stocks go down much faster than they go up, but they go up much more than they go down.”

Your mate in the office is not George Soros

There are always people who claim they sold out entirely three months ago because it was ‘obvious’ prices were too high, or that this or that would happen, or because they had a funny feeling.

I know because people message to tell me how sad they are not to have done the same.

I happen to believe investing edge exists. But it’s vanishingly rare, and it’s never manifested in huge market timing bets that repeatedly pay off.

The fact your nimble friend is not calling you from their private island is a big clue!

Independent financial advisors are not market timing geniuses

A worried friend forwarded an email from their financial advisor. It was sent at what was (to-date) the height of this sell-off in mid-March, and it strongly urged him to sell half of his equities and wait to reinvest when “things were clearer”.

This isn’t necessarily awful advice, depending on the client. That it was blanket guidance was the first red flag. Worse was the IFA claiming that normally they could read the runes of falling markets and get out before major damage – but this one had been too speedy.

It all smacked of self-preservation to me. Your IFA should have set you up with a sensible balanced portfolio, ideally passive, ahead of times like this. Because they happen!

If for some reason you both believe they’re great market timers, the evidence should already be apparent. They’re almost certainly not, and if you hear this kind of thing you might consider getting a new advisor.

Active investing is still a zero sum game

A golden oldie, we’re hearing this crash is a chance for active funds to shine. But the mathematics of investing shows it is impossible for active funds on average to beat the market through stock picking, regardless of whether share prices are up or down.

The average active pound invested will deliver market returns minus higher costs. Active funds’ only advantage over passives – as a group – is actives tend to hold cash to meet investor redemptions. This cash can cushion falls in a bear market. The same cash balance will have held them back in the prior bull market.

Individual funds and managers can do far better than passives of course, whether in rallies or bear markets.

But most will fail to consistently beat the indices, and the snag is always finding the winners in advance. Nothing has changed.

Passive funds have been on a ‘rollercoaster’

I’ve heard several fund management insiders conceding passive funds had a great ten years, but claiming the downside was being on a ‘rollercoaster’.

Firstly, active funds are, with passives, the market. They’re on the same ride.

Second, active investing is a zero sum game so there are no gains to be had for the typical investing pound, just higher costs – rollercoaster or log flume.

Finally most of the last decade was pretty placid in the markets – more like an escalator. Some active managers even bemoaned this as driven by ‘passive mania’ and ‘the Fed propping up the markets’. They blamed it for hurting their returns!

You’re not hearing advice from most fund managers. You’re hearing marketing.

It’s never the time to go all-in on anything

Some now say the crash has proven we’re headed for a depression, and it’s time to go all-in on government bonds.

Some say even government bonds are too risky due to high prices and ballooning government debt. Go all cash!

A few say it’s time to go all-in on equities, because this isn’t the end of the world, shares are cheap, and cash and bonds will deliver lousy returns.

Most of us should never go all-in on anything. The future is uncertain, and a good portfolio reflects that. Sure, have an asset allocation that accounts for your age, your time horizon, your earnings and liabilities – and tilts towards your gut feel if you must.

But don’t bet everything on anything. You could be wrong.

High-quality government bonds bolster your portfolio

For nearly a decade we heard high-quality government bonds were in a bubble that was about to burst. In recent years this turned into the widespread claim that bonds were ‘riskier’ than equities.

This is and was always nonsense. Shares just fell 30%+ in a few short weeks. Bonds held up, as we’d hope they would.

Over the long-term bond returns will probably be lousy. You own some bonds to cushion your portfolio when crashes happen and to sleep at night, not to get rich.

Equities will deliver superior returns in the long run

Don’t mistake that last point for me having any great enthusiasm for government bonds as an asset class right now.

I’m not excited about my house insurance or my smoke alarm, either. That’s not why you have them.

Stock markets will almost certainly deliver far higher long-term returns than government bonds from here. Even long-term bonds are now priced to deliver seemingly derisory returns – barely one per cent per annum in the longest-dated UK issues.

It’s one thing to expect a depression. It’s another to think it will last for 50 years.

Buying shares is hard in a market like today’s, but if you’re a long-term investor you’ll almost certainly be rewarded.

A week or so ago I pointed out that the panic had already been extreme, and it was best now to stick to your plan.

It’s rarely a good time to panic, but too late is never the moment.

Cash is always king

The dash for cash that saw almost everything sell-off in the first weeks of the crisis revived the motto that ‘cash is king’.

Well, cash is always king. It’s predictable like no other asset class. You can buy things with it. It feels good to have a fat wodge.

If I could achieve my aims with cash then I wouldn’t invest in anything else.

Sadly, I can’t. Even the richest person has to guard against inflation, which eats away the real value of a bank account balance like whispered court intrigue whittles away the power of a prince.

Ordinary inflation means 99% of us can’t even consider going all-in on cash, assuming we want to retire some day. The risk of hyperinflation means nobody can.

Despite this, cash is king. Never forget it.

Markets lurch about when they fluctuate

As I said, markets fluctuate. Sometimes they do so wildly, as recently. Because it’s 2020, many blame this on algorithmic trading – particularly those active managers who are forever casting around for a scapegoat.

You can read lots of articles explaining how robot traders have shunted about this or that asset class – let alone individual shares. I don’t doubt they’re a factor.

But markets have always become unmoored in times of panic. These big moves are nothing fundamentally new.

Besides, the programs were written or trained by humans. We’re the same as we were in the 1920s, when we also boomed and bust.

Market falls enable market gains

Stock price falls are what set up your future gains. Without volatility, the returns from shares would be much lower because everyone would own them and bid away future profits.

Lower prices improve expected returns. All those markets everyone fretted were too expensive look a lot cheaper now. For example, Vanguard says the expected return from US shares over the next decade has improved by more than 50%, from 4.4% to 6.8% a year:

(Click to enlarge)

If you’re an active investor who successfully picks stocks, it’s even truer. You make your best buys in bear markets, but you don’t know it at the time.

There is no magic money tree

Plenty of leftwing columnists have asked how the Chancellor has suddenly found hundreds of billions of pounds to support the economy, when there was no money available for their pet projects in the past.

Governments can always create money to pay for spending by issuing debt. But there’s always a range of consequences, from (potentially) higher rates and (often) a weaker currency to (likely) higher inflation or (perhaps) the misallocation of capital and (consequently) lower productivity.

The reason this is less risky right now is because at the same time we’re ‘creating money out of thin air’, the economic shock is effectively ‘destroying money out of thin air’.

The aim is for these to roughly net out.

Do nothing and we risk deflation, or perhaps even a depression. Do something and we’ll hopefully get to worry about inflation sooner than we otherwise would.

Some day we’ll need to deal with these massive borrowings, whether through taxes or by shafting the holders of government debt by inflating away its value. A combination seems most likely. Our economy will be stronger than if we’d done nothing, however, making dealing with the debt more feasible.

Economies need to grow

On the flipside, we shouldn’t think throwing the economic switch into power-saving mode is a trivial undertaking. We will see a monumental short-term hit to growth. The big question is how long the downturn will last, and how easily we’ll be able to pull out of it.

Economic growth isn’t just a boon for billionaires and Davos attendees. Lower growth means fewer goods and services produced for us all to enjoy, plunging tax revenues, and ultimately less money to spend on great things like education, carbon capture, and mammograms.

We are paying to save lives now at the cost of future prosperity, and even some future lives. It will be decades before we have any idea how this equation balances out.

We probably do not face a Great Depression

This is an opt-in recession. Economic growth was recovering before the virus hit. There were not huge structural imbalances in the economy as we went into global lockdown.

This is important. It implies there’s still the hope – though probably not the expectation – of a ‘V-shaped’ recovery when we exit these measures.

Who knows what will happen, but I don’t expect a depression. I believe if things look that dire, then neither the public nor governments will stomach it.

Before that we’d likely try a different tack, such as more aggressive/supportive isolating of the vulnerable and the misunderstood ‘herd immunity’ approach for the rest of us. By then we should have bought time to ramp up breathing equipment for the ill, protective clothing for medical workers, and testing for all of us.

Things can always get worse

I’m not blasé. I can imagine a wide range of dire developments, from repeated and virulent future waves of infection to China going back into lockdown to mass-deprivation in India to political upheavals. You could argue we have all the ingredients for a full-blown disaster.

Heck, maybe another entirely different virus is set to emerge from some swampy hinterland to play tag team with COVID-19 – there’s nothing in the rules that says because we have one we can’t get another.

The pandemic proved this can happen. We’re just more alert to it right now.

Things can also get better

The lockdown could work out better than expected. Spring sunshine could reduce infection rates. We could devise a brilliant treatment that turns infection into an annoyance for even the vulnerable. We might yet discover half of us have already had COVID-19. Eventually there’ll be a vaccine.

Maybe there’ll be an innovation dividend from the crisis. During wartime, hard-pressed societies can achieve in a few months what normally takes years.

Perhaps the miserable trend towards nationalism will be reversed as we’ve been reminded we’re truly all in it together.

FIRE is not finished

I’ve heard people opine the Financial Independence movement is over because the market has fallen 30%.

This is ridiculous on almost every level.

As I’ve said, market drops are not fun but they are normal. Young seekers of financial independence should be pleased at least that shares are cheaper. Good asset allocation for the rest of us takes into account a bit of chop. Those SWR models included periods of big market falls – they just look less scary seen in the past!

I doubt people who saved money and learned to live within their means will regret it as we head into a recession. The FIRE movement was ahead of the game.

We will eat out and go on holiday again

At the end of the day it’s overwhelmingly likely that very little will change from the COVID-19 pandemic – at least if we dodge a second Great Depression.

We will still go to offices. We will still use Tinder. We will still get on planes.

Some pundits have reminded us that people resumed flying after the September 11 attacks – despite worries to the contrary – so we shouldn’t assume airlines are permanently impaired.

This is true, but the recency bias went much deeper than that.

I remember one worthy writer explaining that Hollywood blockbusters were done for, because nobody would want to sit through a reminder of what had unfolded in real-life.

A few lunatics predicted the end of comedy. How could we laugh after such horror?

In reality within a few years Hollywood was making disaster movies about September 11 and everyone flew everywhere.

Time passes.

There will be consequences at the margin when we get through this. I’m sure people will Zoom a bit more, fly a bit less, and working from home will be less frowned upon.

But millions of us have been Skype-ing and working from home for years. If everyone wanted to do it before now they could have. Many people can’t wait to get to back to the office.

We may save a little more money if we can. We will be taxed more. Governments should be better prepared for the next pandemic.

But otherwise life will go on almost exactly as it did in the past.

Invest accordingly.