Franz Kafka’s classic The Metamorphosis sees the central character go to bed a man and wake up as a giant cockroach. Does your mortgage risk a similar transformation in 2022?

Could this engine of wealth creation become a millstone?

It sounds heretical. For more a decade it’s been almost daft not to run a cheap mortgage.

Barely there interest rates made for affordable repayments. Ever-higher house prices and stock markets meant owning additional assets was more rewarding than repaying your debt.

But now rates are rising. Stock markets have crashed, and house price growth is slowing.

Recession talk is in the air.

Sky-high inflation has driven a regime change. Low inflation and near-zero interest rates have given way to expectations of dearer money in the future.

The shift has already hit the highly-rated growth stocks inside your index fund.

But mortgage risk is a bigger existential threat to most of us than wobbly stock markets.

Why your mortgage matters so much

With about eight months to go until my own five-year fixed-rate mortgage ends, I’ve been thinking a lot about mortgage risk.

Having a big mortgage on your personal balance sheet dramatically shifts your financial posture.

And as a lifelong debt-hater, I’ve found having a mortgage challenging at times.

As I told friends who’ve been mortgaged since their mid-20s – and who couldn’t see what I was fussing about – getting a mortgage changes everything.

Because it’s really hard to go bankrupt if you’re not in debt. You can usually alter your circumstances to match your income. The Micawber Principle holds.

Sure we can all imagine scenarios where everything goes to zero and you end up under Waterloo Bridge. But absent debt, a lot must go wrong for that to happen.

With a mortgage though, things are different.

For starters it’s not hard to find yourself with a negative net worth. First-time buyers who put all their savings into buying a home with a 95% mortgage, for instance, are in the red if their house falls in value by just 5%. (Dragging them into ‘negative equity’.)

Bigger price falls might offset ISA and pension savings, putting even wealthier mortgage holders in the hole.

This certainly isn’t fatal in itself.

Crucially, a mortgage is not marked-to-market. As long as you make your monthly payments you’re okay – even if house price falls mean that you’re technically underwater until markets recover.

But what if you lose your job, or there’s some other financial disaster?

You could then struggle to keep up with your mortgage. Especially if mortgage costs are rising as rates climb.

In the worst case the bank repossesses and sells your home, you’re on your uppers – and you still owe the lender whatever is left of your mortgage debt.

Around 345,000 homes were repossessed in the 1990s housing crash.

That’s the nightmare scenario.

Assess your mortgage risk before it matters

I don’t want to overdo this. Interest rates are still low by historical standards, and employment high. And there’s no indication of a house price crash, except for property’s perennial expensiveness.

Personally I’m still mostly happy running my big interest-only mortgage.

I’ve plenty of assets, despite recent market falls. And I can handle a fair few rate rises.

I expect the majority of mortgaged Monevator readers feel the same.

You’ll typically have emergency funds, other investments, jobs, and you didn’t overstretch to buy.

However we’re all at different stages of our financial lives. Some readers will be edge cases.

Besides, the time to prepare is always before a disaster actually strikes.

Complacency kills!

A checklist to assess your mortgage risk

My interest-only mortgage is backed by my investment portfolio, rather than my salary.

And I didn’t get my mortgage like you got your mortgage. (It was personally arranged).

The whole shebang is very different. This means I must consider several moving parts – and different risks – when evaluating my mortgage-related moves.

You can probably do a simpler sanity check. But I think you’ll still find food for thought below.

Let’s get started.

Re-financing risk: what happens when your mortgage deal expires?

For most readers, this is a formality. Provided you’ve still got your job and nothing dramatic has changed, it should be straightforward to get a new mortgage deal when your current one ends.

Remember your initial mortgage was for 25 years or more. Any fixed-rate term of, say, five years was a special bonus period. Your contract runs for 25 years.

This is a good thing. It means that if you don’t get a new special deal, you should just go on to your lender’s standard variable rate (SVR). So you won’t suddenly need to repay your mortgage.

But what you probably want is a new bonus offer.

Let’s say you come to the end of your fixed-rate period. You should probably look to remortgage on a new fix, or some other kind of special rate. This will likely be cheaper than staying on the SVR.

Your best deal could be with your current bank, or with a different lender.

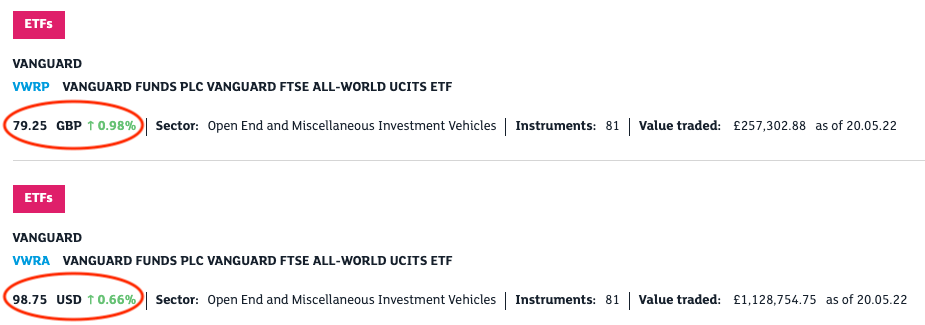

Sitting pretty with higher equity

Your status as a borrower has probably improved since your last mortgage deal.

UK house prices have been rising. This likely applies to your home, too.

You’ve probably also paid off some of the mortgage balance, alongside the interest.

Combined, this means you should have more equity in your home. (Equity is what’s left when you subtract your outstanding mortgage from the value of your property).

More equity usually means access to better rates.

Before, you might have been in the 90% loan-to-value (LTV) mortgage category. But perhaps your greater equity now puts you in the 80% bracket.

Banks will offer you a lower rate compared to somebody with less equity. Lending you money has become less risky. There is a bigger equity buffer against house price falls.

Remember this is mostly helpful for the bank because it protects its loan if it has to repossess your property and sell it. You obviously don’t want it to come to that!

When remortgaging you’ll also have a – hopefully clean – history of making mortgage payments. No longer are you a highly-stretched young schmuck without a track record. That will further increase your appeal to lenders, compared to when you were a first-time buyer.

So shop around.

Look out for early repayment charges: Most mortgage deals come with a penalty charge for early repayment of the mortgage for as long as the deal lasts. For instance I faced a 5% penalty in the first year of my five-year term, falling to 1% in the final year. However I can pay off 20% of my outstanding balance every year without penalty. Check your small print. Also: sometimes it may be worth paying a penalty charge to secure a new mortgage deal at a lower rate.

What if you lost your job?

If there’s been a big change in your circumstances you may struggle to get a new mortgage deal.

That’s because you could be asked to prove your income and other details such as credit card debt as part of your application for the new deal, just like when you first got your mortgage.

However at worst you should just revert to continuing on your lender’s standard variable rate. Your home ownership is not immediately at threat.

The downside is the SVR is probably costlier than with a deal. You’re also exposed to future mortgage rate rises (or cuts).

I’d suggest it’s nearly always better to lock in a fixed-rate mortgage when you can.

Even if you believe interest rates might not rise much more – or fall – the security of having a fixed schedule of mortgage payments is valuable.

Not sure where you’ll stand when your current deal ends? Give your bank a call so you can prepare.

Repayment risk: keeping up as mortgage rates rise

However you refinance your mortgage, you may well have to pay more each month because mortgage rates have been rising.

To state the obvious: higher mortgage rates mean higher monthly payments.

Can you cope? Do your sums to see if you should already be rethinking your budget.

I covered stress testing your mortgage against rates rise in my last post.

Please read that if you haven’t. Rising rates is the biggest mortgage risk for most people.

Interestingly, however, there’s been a development since my last article.

The Bank of England has told lenders they no longer have to stress test borrowers to check they could afford to pay with much higher mortgage rates. The central bank believes that restrictions on loan sizes as a multiple of income will be sufficient to keep things under control.

Maybe so, but it seems a curious decision just when rates are rising. If the Bank wasn’t politically independent you’d smell a rat.

With respect to today’s topic though, this shift might make it easier for some people to remortgage in a pinch.

Remember, the high inflation ushering in higher rates is also eroding the real value of your outstanding mortgage. That is definitely a good thing.

However you need to keep up with your mortgage payments to benefit.

Repossession in an economic downturn is to be avoided at all costs.

House price crash risk

This brings me onto the potential for house prices to fall.

Lower house prices is not a direct mortgage risk.

Unlike with a margin loan with a stock broker, for instance, your bank does not constantly reassess the value of your home and demand more cash if your equity falls below a critical threshold.

That’s one reason why a mortgage a relative safe kind of personal debt.

The other reason – for you and your lender – is a mortgage is secured against your property.

This asset-backing is why you can borrow to buy a home at 3.5%, but credit card debt costs 25%.

But it’s also why falling house prices are a tangential mortgage risk.

If lower property prices mean the equity in your home has fallen when you remortgage, you could have to agree a more expensive deal.

And if you’re in negative equity you could end up stuck on your lender’s SVR.

Buy high, sell low

And what if you need to sell your home when house prices are down?

At best you’ll lose out because you have less equity in your home to get as cash after the mortgage is paid off.

At worst, your house sale won’t cover the mortgage. You’ll be in arrears.

Unlike in some countries – and several states in the US – you can’t walk away from this debt in the UK. You’re still liable for the shortfall, even though you’re no longer a homeowner.

There are rules, though. If it happens you’ll definitely want to seek advice.

And banks really don’t want to go down this road. It is expensive, and bad for publicity. They will usually try to agree some new payment schedule.

We can’t be sure that would happen in a really deep downturn, though.

Keep up your payments and you’ll be okay. But this is a mortgage risk, hence I list it here.

(Further) stock market crash risk

Fewer Monevator readers will need to worry about lower share prices with respect to their mortgage.

Indeed for most people in the accumulation phase of life, a stock market crash – and the chance to buy shares cheaper – is a good thing.

But if, like me, you’re on an interest-only mortgage that’s meant to be paid off by investment returns – or maybe you’ve still got a market-linked endowment mortgage from the 1990s – a drawdown in your portfolio could matter:

- In the short-term, there’s the risk your portfolio falls a lot and at the same time your bank checks on whether your repayment vehicle is on-track. You can chant ‘be greedy when others are fearful’ to bankers all you like – they will only lend you an umbrella when it’s sunny. Banks will be spooked by a portfolio decline. This will probably limit your options if you want to agree a new deal – perhaps to address a projected shortfall – such as extending the mortgage term.

- In the long-term, there’s a danger that your future investment returns leave the portfolio unable to cover the mortgage. In my case this would require negative nominal returns over the next 20 years! Not impossible, but I judge it to be low risk. You’ll have to do your own sums.

As I said, borrowers with endowment mortgages from the ’80s and ’90s have already trod this ground.

At one point there was lots of talk of an endowment shortfall crisis in the UK, and of how this might also encompass struggling interest-only mortgagees.

We don’t hear much about it now. Products and strategies were created to help usher older mortgagees over the line, and I expect many just sold into a stronger market and downsized.

The bottom line is anyone reading Monevator with an interest-only mortgage should be on top of their finances. Don’t assume another decade of high returns like the last one will bail you out. Contribute more money to your investments, or consider doing something else like shifting to a repayment mortgage or even selling up while house prices are strong.

Personal risks: health, job, moment of madness

Finally a broad catch-all covering all kinds of developments in your personal life.

Clearly if I could forecast whether you’ll be hit by a bus or suffer a stroke, I wouldn’t be writing a financial website.

However some kinds of massive disruption are predictable – and yet you might not have associated them with your mortgage before.

For example I’ve known couples set to divorce who’ve put off (un)doing the deed for years. This could be a big mistake if you find yourself having to divvy up a house in the midst of a house price crash, or if the main breadwinner is made unable to meet the payments.

Or perhaps you’ve known health problems that will eventually see you leave work, but you’re soldiering on for now? From the perspective of your mortgage it may be better to bite the bullet and downsize to get mortgage risk off the table, to avoid being hit by a double-whammy in the future.

I also think it’s fair to say the risks of running a mortgage increase with age – although there comes a point where it’s more your bank’s problem than yours!

The inescapable truth is a healthy young 30-year old has more time to correct missteps than a 60-something near-retiree. Act accordingly.

Be prepared

Given the shifting financial landscape, I believe it’s a good time for everyone to think about mortgage risk – and any upcoming remortgaging plans – and to consider what could go wrong.

Channel your inner Chicken Little. Imagine the sky is falling.

Could you be squished like a chicken nugget?

Let us know in the comments below.

In a couple of weeks I’ll return to my own mortgage, and give an update as to where I’m at as a result of all this thinking. Subscribe to make sure you see it.