Let’s say you have £10,000. There’s no rule that says you have to invest it.

In fact, many people would spend it!

Why not put it under the mattress, and leave it for a rainy day?

One word: Inflation.

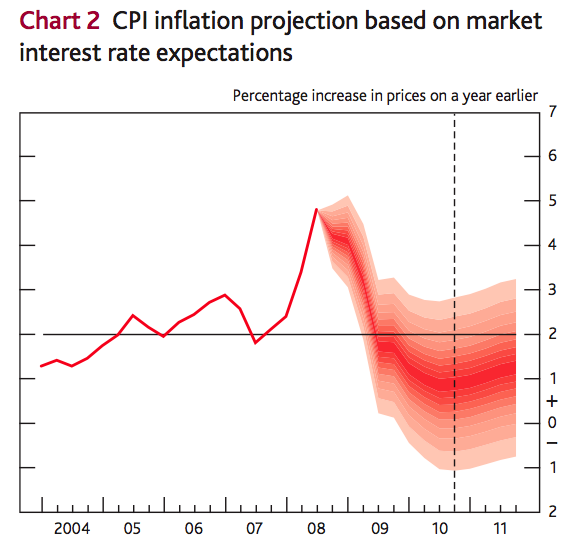

Take a look at this graph:

This graph shows how what you can buy with £10,000 falls over the years, due to the impact of inflation.

Inflation is the tendency for the cost of things – bread, houses, wages – to rise.

As such it reduces the spending power of your money each year.

- In 25 years time, you will still have £10,000 in nominal terms. Your twenty £500 notes will still be under your mattress, and the Queen of England will still be frowning at you.

- But in real terms the spending power of your money will be diminished.

The graph shows the impact of just 2% annual inflation on your money.

2% reduces the value of your money by only a little bit each year, but it adds up to a 40% loss in real terms over 25 years.

The inflation rate can rise and fall

The Bank of England and many other countries target a 2% inflation rate.

But sometimes, such as in the 1970s, inflation can rise to 5-10%. Such a high inflation rate can halve the value of your money in less than a decade.

Inflation can get even worse in extreme situations, such as 1920s Germany or Zimbabwe more recently. Hyper inflation in a crisis can hit triple digits or more.

The first reason we invest is to maintain the spending power of our money. Every year we need to grow our savings by at least the rate of inflation.

Generally – but not always, and especially not in recent years – you can keep up with the rate of inflation by keeping your money in a good cash savings account.

Cash accounts pay interest on your total savings. By adding this interest to your existing pile of money, you can grow your savings over time.

This may seem trivially obvious, but it’s an important point.

The spending power of each £1 still goes down over time. But by growing the total amount of £1s in your savings pot by earning interest and reinvesting it, you can aim to offset the impact of inflation and maintain the spending power of your total savings.

In the graph above:

- The blue line shows how your £10,000 grows over 25 years with 2% interest. This is the amount you see piling up in your bank account.

- The red line shows how £10,000 would lose its value in real terms at 0% interest. For example, if kept under your mattress!

In reality you will get interest and see your wealth rise but – invisibly – each pound in your bank account will also lose some of its spending power due to the impact of inflation at the same time.

If inflation was running at 2% for the entire 25 years and interest rates were also 2%, then the two would cancel each other out.

This is shown in the green bar in the following graph, which is the real spending power of your money, with 2% interest and 2% inflation.

You’d very rarely see inflation and the interest rate on your cash savings exactly matched like this, of course, let alone for 25 years! 1

Some times interest rates will easily outpace inflation. At other times it will be very hard to get a real return, especially if you pay tax on your savings.

But the principle is clear. At the very least, you need to grow your money in nominal terms, just to offset the corrosion of inflation.

Investing like this will at least maintain the spending power of your money.

Key takeaways

- The real value of £1 decreases over time, due to inflation.

- Over the long-term, this can seriously reduce your wealth.

- At the least, we need to invest to offset the rate of inflation.

This updated post is from our occasional series on investing for beginners. Subscribe to get our articles emailed to you (we publish three times a week) and you’ll never miss a lesson! And why not tell a friend to help them get started?

- Some interesting products such as the government’s sadly suspended index-linked savings certificates did enable this, plus a bit of icing on top.[↩]

Comments on this entry are closed.

This is exactly why National Savings and Investments Index-linked Savings Certificates is so valuable. It allowed you to maintain the spending power of your savings plus a little on the side. Unfortunately, it is not available for the foreseeable future.

Actually, I do not think it is generally possible to really keep up with inflation in saving accounts. It is difficult to do so when you have little idea what inflation will be in a year or five years time. Would be quite unfortunate to lock up savings for two years at 2% only to find out that inflation went up to 5%.

@Joe — It is absolutely possible to keep up with inflation using cash in normal times, save for the possible complication of tax (which most people of moderate means can handily sidestep with an ISA).

The real return from cash in the UK has been positive over the last 10 years, the last 50, and since 1900. The long term real return is just shy of 1%. Those are institutional class returns — nimble consumers who rate tarted to chase the best accounts over the years from 2000 to 2010 could see returns well in excess of that.

All that said I too miss NS&I index linked certificates. They were a real boon for cautious savers, and I’m glad I’ve got at least some money in them.

Such a simple chart but so clear to see the power of even a small return on the whole wealth building process.

@ The Investor

Whether it’s possible to keep up with inflation by holding cash depends what you mean by inflation and whether you believe the government’s figures.

Before I’m accused of conspiracy theories let me explain the main problems I have with the way we measure inflation:

1. What’s (not) included. The main issue here is that CPI has become the preferred measure. Unlike the previously used RPI, we now ignore own-occupier housing costs and therefore house price rises. I don’t think those massive increases in council tax during the 2000s got factored in either.

2. Weightings. Inflation is a weighted average with some prices given more importance than others. The latest figures tell us CPI has decreased to 2.4% in April 2013. But this is mainly because air fares and forecourt petrol prices have fallen – transport costs are given a weighting of 16.1%. Whereas food is only weighted at 12.1%, and in this rather important category of expenditure we’ve seen some double digit rises recently. And because CPI reflects the ‘average’ consumer there is a massive weighting of 28.6% for recreation, culture, restaurants and hotels. If you’re saving because you want to fund your expenses in retirement then what you really need to keep up with is the price of essentials – it hardly helps you buy your groceries just because iPhones have got cheaper, for example.

3. Calculation method. Most people would think you get an average by adding everything up and dividing by the number of things you’re measuring. Not with CPI – this uses the ‘geometric mean’ to calculate the average using a square root method which, what a surprise, always comes out with an answer that’s at least 0.5% lower.

By the way, inflation hit 25% in the 1970s, not the 5%-10% you suggest above. And in my opinion we’re heading back in that direction.

I’d back what The Investor is saying in terms of current inflation just through my own experience of living day to day. I certainly feel that my money isn’t going as far as it used to, despite trying to keep tabs on it. And some things are moving upwards faster than others. When I look at hotels I once used to holiday in, for example, they’re now beyond my reach.

@BeatTheSeasons — It’s true that RPI inflation in the 1970s peaked at 25% for a short period, but I think my numbers are a better representation of inflation through the whole decade. (I haven’t done the maths specifically, and would concede it’s on average likely nearer 10% than 5%). I’m not really a fan of taking short-run numbers in isolation. (A similar example is the oft-quoted interest rate peak in the early 1990s, that lasted for literally about 3 hours!)

As for the calculation methods and so on, I’m not really too bothered by any of that to be honest.

I’ve seen the arguments made about this or that innumerable times over the years. I don’t doubt governments do tweak the basket to their own ends, but time and time again you see the bugbear goods and services of the inflationists in one year have in many cases almost inverted a few years later. Nobody’s personal inflation will exactly match the purported basket, but at least in the UK I’m satisfied there’s no grand conspiracy going on.

What I mean by keeping up with inflation is numbers from the likes of Credit Suisse (I am quoting their very well respected Yearbook 2013) which shows that deflating for inflation you have a long-run real return of 0.9% from UK cash. No offence, but I am happy to take their word for those numbers and their methodology. 😉

There are plenty of places on the Internet of course where tin hits can be donned and numbers dissected and potential inflation rates of 25% can be drooled over despite their being absolutely no sign of it in any numbers currently (quite the opposite) and more power to you if that’s your thing, but I’d prefer we didn’t do so here on this post, which is really targeted at newcomers to investing. Thanks! 🙂

“One word: Inflation” isn’t true historically. For example from somewhere around 1820 to 1914 prices in Britain were as likely to decrease as increase but people still invested. Why? For future income.

What inflation does, I think, is influence which investments you might make. If you think that you might be investing for a period that could include 1970s-like inflationary spikes, you might rather invest in equities than in Gilts. Indeed, what you invest in must be largely determined by what you fear in the future. If you expect some lunatic government to introduce a modern equivalent to the Rent Act, you’ll avoid BTL property; if you expect a depression so severe that prices fall, then Gilts would look attractive.

Since none of us can be certain what the future will bring we might diversify our investments. Trouble is, at the moment almost everything seems pretty pricey to me. Thank God for those ILSCs we bought.

@dearieme — Deflation is completely compatible with what I’ve written. 🙂 In a deflationary environment, you don’t *need* to invest, and cash under the mattress is fine — you get richer over time just sleeping on it. Of course there’s many reasons why you might still choose to invest, such as future income as you say or speculation or what have you. The presence of inflation is the reason why you *have* to if you want to even stand still, however.

@BeatTheSeasons — Re-reading my comment above, it does sound a little fierier than I meant, even with the smileys. I don’t mean anything personal by it, and appreciate you sharing your thoughts, but I am pretty allergic to that topic after repeated exposure. And as I say, I don’t think this is really the article to debate it around. Cheers!

@ The Investor

None taken. I don’t personally have a tin hat, a gun, gold or land (except my back garden). Perhaps I need to diversify!

Many commentators agree that the unsustainable level of government debt, among other factors, makes a period of significant inflation inevitable. Hopefully not even as high as 5%-10% but having said that prices will double every 10 years at a rate of just 7.2% – a terrifying prospect if you’re not prepared for it.

I always think I should make an effort to look after the elderly, starting with future me, who will be very glad that young me had a bit of perspective.

@Investor

Have you been reading Money Moustache too much recently?

Can we expect a “face punch” and a slew of “*&$%^**X” for non-PC opinions in the future?

Might make the comments section fun…

On the more serious/useful side cash does have its place, perhaps more than you give credit for above

It really has value both in deflation and when other asset are really overvalued

I held a lot of cash and short dated US/UK government debt (maybe nearly 50% at peak) in late 2006-2008 and I was very glad I did in 2009, when I could buy shares and corporate bonds at levels which now look like bargains

In 17th century Holland, should you have diversified into tulips?

Re long term real returns on cash. I recall that the Barclays EG study reckoned it to be around 0.8%, so those numbers seem about right. It’s worth remembering, though, what a lot of disgruntled savers seem to have forgotten, that through the 1980s, 1990s and some of the 2000s, real returns were much higher. This indicates that the road to regression to the mean may be a long one.

> we invest is to maintain the spending power of our money

I disagree. You save if you want to do that, preferably in NS&I ILSCs.

In fact after a few years of reading this site, I am prepared to categorically assert that TI does not invest to maintain the spending power of his money. He does it in the anticipation that his money will make money 😉

@Neverland — I agree with you cash has plenty of attractive qualities, as you’ve probably noted from my glowing missives on the attractions of the stuff. 🙂 I’ve even suggested a new investor can start with nothing more than a simple cash/tracker split.

These lessons will be about unpacking investing from the bottom-up, though, rather than exhaustive coverage of asset classes or what have you.

This brings us to the comments, and the potential for face punching and so forth. (Not likely, and besides MMM does it so well already…)

One trouble with blogs is they are very un-selective in their audience when it comes to any particular article. So you can get a lot of regular and fairly expert readers talking their hobby horses sometimes, on posts that aren’t really relevant for it and where it might confuse the intended audience or are simply unrelated. We’re blessed with thoughtful and articulate readers on Monevator, but that doesn’t entirely get around the issue, and I can see it coming up again in future posts in the series.

We have a community that likes to discuss things, I guess. What I should probably do is switch on the Forum I’ve had lurking set-up but unused for six months now. After dealing all year with server-crippling comment spam from China I’m wary about the admin though, to be honest.

Right, now I’ve gone way off topic too, so will shut up! 🙂

Timely article for myself and agree its an important lesson for newer investors. My nsi index linkers are maturing and I’ve been umming about renewing or not. Inflation certainly hasn’t spiked like I have expected it too yet, but maybe it’s due a correction. I think this one is so hard to call though, it does seem that we can’t trust governments to control things with crazy debt abound.

Interesting debate as always chaps.

Hi, to someone who may not understand finance all that well your graph looks like that by saving in cash at 2% it will be worth £10k more after £25 years.

@Geo

Apparently the roll-over option for NS&I is RPI +0.25% – not exactly generous, but better than anything else available 🙁

I have some coming up for renewal too soon 🙁

David, to me it looks like it goes from £10k to £16k in 25 years (an increase of £6k/60%). That’s the effect of interest.

Because inflation happens at the same time, you need to look at the final value of the £10k after inflation as well (£6k).

The true value of the money is total with interest (£16k), minus the inflation-adjusted total (£6k), leaving £10k (i.e. you broke even).

At least, that was my understanding of the example 🙂

@Geo,

A good question about renewing index-linked certificates. I have holdings built up since the 1980’s when that grossly overrated chancellor (not least by himself!), Nigel Lawson, offered RPI + 4% which as a 40% tax payer I snapped up. A lesson here is that if you perceive a government is pursuing ideologically-driven lunatic policies from which you can benefit and you don’t find it morally repugnant, seize the opportunity. There is also the added pleasure of winding people up!

A consideration re renewing index linkers is that one cannot assume that the current end of term roll over arrangements will exist in perpetuity and there is a risk that you end up being forced at some point in the future to take cash during a period of negative real interest rates.

I’m operating on the assumption that index linkers will probably cease to be available even via roll over and new contributions to ISAs will either be limited or axed completely.

A further consideration is that early withdrawal from index linkers is now penalised.

If I had to choose between index linkers (not currently available) and a stocks and shares ISA for new savings, I’d chose the latter. If I were unable to afford to save into a S&S ISA from income and had maturing index linkers, I’d consider cashing them in and investing the proceeds into a ISA, possibly by drip-feeding.

There is also the possibility that existing ISA investments could become subject to tax but along with capital gains tax on residential property, regard as measures only likely to be introduced in extremis when we’d all have rather more serious things to worry about!

This is off-topic but if you want to try to anticipate likely changes to tax and benefits take a look at http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/news/neilobrien1/100043679/50-billion-of-welfare-spending-a-third-goes-to-people-on-above-average-incomes-do-we-really-need-this/ . It’s out of date and there have been many changes since 2010 but I think it still makes interesting reading.

@David @Luke — Yes, I can see it’s potentially a tad confusing. I hope it’s a bit clearer if they read the text, too (although if they selectively edit like my good friend @Ermine I may not succeed 😉 I did say “the first reason” to invest… There’ll be something on nefarious speculation to come. 😉 ).

@All — Re: Rolling over the NS&I linkers, I don’t think +0.25% is terrible for what you get in our purportedly low return world, though superficially rotten compared to the old days of course. I’ll roll over just because they’re not issuing them anymore, and it’s too valuable a diversifier to let go of.

Nicely pitched article, kudos for recognising the huge gulf potential investors have to cross inorder to make sense of even good blogs and books.

I’m almost embarrassed to admit it took me a couple of years to “discover” the concept of real return when I was sifting through the ashes of my portfolio in 2009. I say almost embarrassed as it’s not a measure that the financial services industry promote too heavily and most investment blogs and books just assume you know.

Perhaps you might have been a little more forceful in pushing the concept of real return as your key takeaway ?

On the subject of assumed knowledge, I had to ask what

index linked savings certificates were a couple of years ago (you can’t google ILSC !). Fortunately I just managed to get some in the last issue, now I get misty eyed every May when ns&i fail to offer new ones.

I look forward to the rest of the series, particularly when you talk about risk 😉

Thanks for the thoughts. The renewals are now only offering 0.15% plus inflation, not great but it’s really case of where else.

I did potentially think the charts was confusing, I guess because one thing takes inflation into account an other doesn’t, not sure if that’s allowed 🙂

I interested to see what mr monkey with a pin has to say about inflation if he gets his book out on the subject. Probably wont be pleasant reading.

@All — Guys and gals, I took on-board your comments and added a third graph and some text.

What do you think, is this clearer now? I am worried it’s getting a bit long and complicated, but hopefully it really spells it all out…

@Investor – Looking good now!

Such a great article for those who do not understand why it’s important to invest. Now I know where I should refer to make my point more clear 🙂

I’d argue that you can increase the return on cash to some degree by self insuring small things – ie a pot to replace dental insurance, a pot to replace pet insurance, boiler cover, etc

Also if you’re only going to buy something once and never again, ie new bed for kids, renovations/building extension, once in a lifetime cruise, then buy it sooner rather than later if all you’re trying to do is keep up with inflation

And harness it to your advantage, pensions over mortgage – companies raise prices & profits with inflation while their debt erodes – overall an indebted stock can leverage inflation – and debt of one kind or another being the origin of risk.

This whole game is how you choose to play that force of nature – whether you use a chisel or a pneumatic drill to harness it

I’m so glad to see somebody else is banging on about this too. So many people aren’t aware of the power of inflation & the impact on savings.

I always thought it would be so powerful if mainstream finance had to advertise their headline interest rates both pre & post inflation. Marcus doesn’t look that great anymore then!

Seriously though – it’s getting harder these days to get a decent return without taking more and more risk. Just hopefully knowingly.

@ TA

A really useful, down-to-earth summary. If I had a hat, I would take it off to you…

@TI

CPI is also affected by adjustments for ‘hedonic improvements’. For example, the cost of a B/W TV is £50.00m and the cost of a colour TV is £75.00. But because of the hedonic improvent between B/W and colour, no inflation has occured! American but relevant:-

https://www.ottawagroup.org/Ottawa/ottawagroup.nsf/home/Meeting+4/$file/1998%204th%20Meeting%20-%20Moulton%20&%20LaFleur%20&%20Moses%20-%20Research%20on%20Improved%20Quality%20Adjustment%20in%20the%20CPI%20The%20Case%20of%20Televisions.pdf

I agree with Matthew. Govt recorded inflation is not the same as personal inflation (although it’s a useful measure to keep an eye on). My basket of goods is not the same as others.

Buying discounted goods in bulk is a good way to protect yourself. For example, as a keen runner I always pick up trainers with unpopular colours end of season – and usually grab up to half a dozen pairs if they are a model I know fits well. Ditto running gear. That means my running costs(!) are rarely more than 20-30 quid a year. And fairly consistently too. Sure there’s some danger of opportunity cost. But when you are locking in up to 70% savings over normal prices each time (as I do with trainers), it would have to be a hell of an investment to beat it.

Other goods like washing powder are also bought in bulk. Solar panels were bought as a hedge against future energy costs (as partly was our woodland).

Choosing secondhand – especially of electronics – is another good way of avoiding inflation.

Also useful if your income is lumpy. Your lean yeared self will thank the foresight of your frugal fat yeared self.

‘Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?’ first aired in the UK in 1998. £1m in 1998 was worth just shy of £1.8m in today’s money according to the BoE inflation calculator.

Inflation is an important base line measure. But something to be aware prior to retiring, is whether the sum you’ve accumulated can be withdrawn annually at a rate that keeps pace with standard of living, I’d suggest measured by average earnings.

If average earnings outpace inflation, and your benchmark is inflation plus whatever investment returns you need to maintain your current lifestyle, then you could be in the comfortably-off demographic when you retire, but after a few decades your annual income has fallen well behind average earnings, and you find yourself a relative pauper.

Hi @W, I’m probably being a bit dim but I don’t quite understand your logic, above.

I suppose if average earning go up, and ‘everyone else’ can therefore afford whatever the fancy wizzy new gadget or experience is, then if you’ve only kept up with the inflation of a basket of ‘essentials’ then I can see your point. If you keep up with inflation you maintain your current standard of living – but can’t ‘keep up with the Jones’s’ maybe? But unless you’re a super early retiree, most evidence suggests people’s needs reduce with old age, if anything.

So I guess perhaps I do see your point… you might end up as a ‘RELATIVE’ pauper, but I’d argue you will maintain your ‘ABSOLUTE’ standard of living.

I guess it depends what you aspire to.

MoMo

For retirement I think it makes sense to use an inflation protected/increasing annuity for the basic cake layer of what you need that might inflate (bearing in mind there might be no mortgage to pay, and remember the state pension!). You could in theory cut out the middlemen with linkers but an annuity as a package has more fscs coverage

And have a seperare more adventurous cake layer for luxuries (leaving an inheritance is a luxury, not a need, so I think that everyone needs some sort of annuity/DB pension/willingness to work in retirement)

Bear in mind decreasing mobility with age, and possible nursing home costs taking whatever you haven’t spent – if you don’t blow it someone else will. I also don’t think you need to give the next generation a leg up so much as you can just teach them to invest – so they don’t feel like they can’t keep up with house prices and they have a feeling of independence and success off their own back

@MoMo

“I suppose if average earning go up, and ‘everyone else’ can therefore afford whatever the fancy wizzy new gadget or experience is, then if you’ve only kept up with the inflation of a basket of ‘essentials’ then I can see your point”

Yes, that was my point. And it’s not just wizzy gadgets, but travel, health care and everything else that contributes to quality of life.

I agree that if you keep up with inflation your spending power has remained relatively unchanged. But again as you say it depends what you aspire to, and over a long retirement that’s a question that deserves a lot of consideration.

It may not be possible to invest for returns that keep your standard of living improving in step with the working polulation, but the consequences are often not considered.

It is worth noting that ILSC’s are not subject to deflation. According to the key features document “If there is a decrease in the CPI, the value of your Certificate will not reduce.”.

@The Borderer:

FYI, from Paul Johnson’s 2015 paper: UK Consumer Price Statistics: A Review, hedonic adjustment applies to “0.73 percent of the index”.

@TI

FWIW, I agree with you that:

“Nobody’s personal inflation will exactly match the purported basket, but at least in the UK I’m satisfied there’s no grand conspiracy going on.”

@TI:

For info:

decadal UK average RPI (Sep – Sep)

1910’s 14.7%

1920’s -2.8%

1930’s -0.5%

1940’s 3.9%

1950’s 4.1%

1960’s 3.7%

1970’s 13.0%

1980’s 7.0%

1990’s 3.6%

2000’s 2.6%

2010’s 3.1%