If you’re wondering whether your asset allocation is right for you, then running it through our favourite investing rules of thumb is a great way to test your thinking.

Too often asset allocation is reduced to a single variable – age – whereas in reality a portfolio that lets you sleep at night also depends on:

- How much risk you can take

- How close you are to achieving your objective

- When you actually need the money

- Your individual response to market turmoil

Each of the heuristics below helps you reexamine your asset allocation along one of those dimensions. All are more directly relevant than your age alone.

After all, there are 70-somethings capable of weathering a stock market storm like Easter Island statues. 1

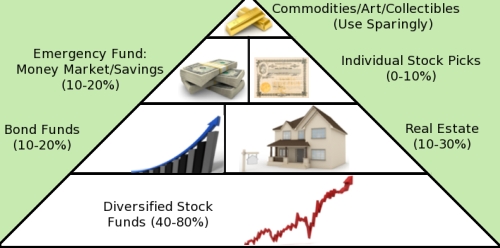

Before we start – Each rule of thumb offers a maximum equity allocation. The remaining percentage of your portfolio is divided among your defensive holdings. Choose wisely and you should be appropriately diversified in other asset classes whenever stocks take a dive, as they inevitably do.

Okay, let’s have at it.

What’s your timeline?

How long do you think you’ll invest for? The closer you are to needing the cash the less Larry Swedroe thinks you should hold in stocks:

| Investment horizon (years) | Max equity allocation |

| 0-3 | 0% |

| 4 | 10% |

| 5 | 20% |

| 6 | 30% |

| 7 | 40% |

| 8 | 50% |

| 9 | 60% |

| 10 | 70% |

| 11-14 | 80% |

| 15-19 | 90% |

| 20+ | 100% |

This heuristic highlights how we’re better able to bear the risk of holding equities when we’ve got more time to recover from a stock market setback.

Or – to look at it from the other end of the telescope – it’s sensible to switch to wealth preservation rather than growth when time is short.

A retiree might adopt a minimum stock floor if they intend to remain invested for the rest of their life. Whereas it makes sense to be entirely in cash in the last few years if you’re investing to buy something specific, such as a house, annuity, or child’s education.

Tim Hale provides a simpler version of this rule in his UK-focused DIY investment book Smarter Investing:

Own 4% in equities for each year you will be investing. The rest of your portfolio will be in bonds.

What’s your target number?

This rule is great for budding FIRE-ees and anyone else charging towards a defined financial target. Jim Dahle shows how you might sync your equities with the amount of your goal achieved:

| Percentage achieved | Max equity allocation |

| 0-10% | 100% |

| 11-30% | 80% |

| 31-60% | 70% |

| 61-90% | 60% |

| 91-110% | 50% |

| 111-150% | 40% |

| 151%+ | 20% |

Once you’ve gained some experience, you can easily adjust these numbers to suit your individual risk tolerance. I also like the way Dahle’s guideline nudges an investor to:

- Take more risk off the table if you over-achieve. (That is, to stop playing when you win the game)

- Increase your stock allocation if a crash knocks you back

Most people will probably feel burned in that latter scenario, and may struggle to buy more beaten-up shares. However there’s a strong chance that stock market valuations will be indicating it’s a good time to load up on cheap equities.

How big a loss can you take?

So far we’ve looked at asset allocation strategy from the perspective of our need to take risk. This next rule considers how much risk you can handle.

Swedroe invites us to think about how much loss we can live with before reaching for the cyanide pills:

| Max loss you’ll tolerate | Max equity allocation |

| 5% | 20% |

| 10% | 30% |

| 15% | 40% |

| 20% | 50% |

| 25% | 60% |

| 30% | 70% |

| 35% | 80% |

| 40% | 90% |

| 50% | 100% |

I’m always amazed by how many people believe that their investments should never go down. It’s a valuable exercise to be confronted with the idea that you are likely to be faced with a 30%-plus market bloodbath on more than one occasion over your investment lifetime.

Personally I found it next to impossible to imagine what a 50% loss would feel like – even when I turned the percentages into solid numbers based on my assets.

At the outset of my journey, my assets were piffling. So a massive haemorrhage didn’t seem all that.

Experience is a good teacher though, and it’s worth reapplying this rule when your assets add up to a more sizeable wad. You may feel differently about loss when five- or six-figure sums are smoked instead of merely four.

The Oblivious Investor, Mike Piper, uses a slightly more conservative version of this rule:

Spend some time thinking about your maximum tolerable loss, then limit your stock allocation to twice that amount — with the line of thinking being that stocks can (and sometimes do) lose roughly half their value over a relatively short period.

Just remember that stock market losses can exceed 50%. It doesn’t happen often but it does happen.

Read about the worst collapses to hit UK, Japanese, German, and French investors if you really want to scare educate yourself.

How do you respond in a crisis?

It’s hard to know how painful a serious market crunch can feel until you’ve been run over by one yourself. It’s never fun, but at least you can put the ordeal to good use afterwards.

William Bernstein formulated the following table to guide asset allocation adjustments after your portfolio has dropped 20% or more, based on what you did while it was busy slumping:

| Reaction during crisis | Equity allocation adjustment |

| Bought more stocks | +20% |

| Rebalanced into stocks | +10% |

| Did nothing but didn’t lose sleep | 0% |

| Panicked and sold some stocks | -10% |

| Panicked and sold all stocks | -20% |

Bernstein believes actions speak louder than words. If you didn’t sell up but you also didn’t feel comfortable buying into a falling market then your asset allocation is probably about right.

If the setback made you feel miserable or panicked, adjust your stock allocation downwards. It’s probably too risky for you at current levels.

Reapply this test throughout your life. Your risk tolerance may well change over time – especially with greater assets.

If you’re worried the market is too expensive

Another technique advocated by William Bernstein is overbalancing. He recommends it as a method of gradually reducing your exposure to a market that may be overvalued.

Here’s Bernstein’s explanation: 2

If the stock market goes up X%, you want to decrease your asset allocation by Y%.

What’s the ratio between X and Y?

If the market goes up 50%, maybe I want to reduce my stock allocation by 4%. So there’s a 12.5 ratio between those two numbers.

Well, that’s what it really all boils down to: What’s your ratio between those two numbers?

Bernstein is indifferent as to whether your allocation changes by 2%, 4% or 5% in response to the big market shift.

Like most heuristics this one is based on intuition-driven experience. It’s not a scientific formula, hence you can adjust it to suit yourself or ignore it entirely.

Keep in mind that usefully predicting market valuations is extremely difficult.

The Harry Markowitz ‘50-50’ rule of thumb

If all that sounds a bit complicated then consider the oft-quoted approach of the Nobel-prize winning father of Modern Portfolio Theory.

When quizzed about his personal asset allocation strategy, Markowitz said:

I should have computed the historical covariance and drawn an efficient frontier. Instead I visualized my grief if the stock market went way up and I wasn’t in it – or if it went way down and I was completely in it. My intention was to minimize my future regret, so I split my [retirement pot] 50/50 between bonds and equities.

The ‘100 minus your age’ rule of thumb

This rule of thumb is so old it belongs in a rest home. But it’s still got legs because it’s very simple:

Subtract your age from 100. The answer is the portion of your portfolio that resides in equities.

For example, a 40-year-old would have 60% of their portfolio in equities and 40% in bonds. Next year they would have 59% in equities and 41% in bonds.

A popular spin-off of this rule is:

Subtract your age from 110 or even 120 to calculate your equity holding.

The more aggressive versions of the rule account for the fact that as lifespans increase we will need our portfolios to stick around longer, too. That often means a stronger dose of equities is required.

Following this rule of thumb enables you to defuse your reliance on risky assets as retirement age approaches.

As time ticks away, you are less likely to be able to recover from a big stock market crash that wipes out a large chunk of your portfolio. Re-tuning your asset allocation strategy away from equities and into bonds is a simple and practicable response.

The Accumulator’s ‘rule of thumb’ rule of thumb

Here’s my contribution:

Rules of thumb should not be confused with rules.

I have to say this, of course, lest the pedant cops shoot me down in flames, but it’s true that rules of thumb are not fire-and-forget missiles of truth.

They are exceedingly generalised applications of principle that can help us better understand the personal decisions we face.

(Hopefully Monevator’s long grapple with the 4% rule has seared that into our brains!)

The foundations of a proper financial plan are a realistic understanding of your financial goals, your time horizon, the contributions you can make, the likely growth rates of the asset classes at your disposal, and your ability to withstand the pain it will take to get there. (Amongst other things…)

But rules of thumb can help us get moving and, as long as they’re tailored to suit, can start to tackle questions to which there are no real answers such as: “What is my optimal asset allocation strategy if I wish to be sitting on a boatload of retirement wonga 20 years from now?”

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

What about the % tied up in one’s home or other real estate?

Thanks, useful stuff, and very well timed for me.

I’d love to see similar guidance regarding geographical diversification within one’s equities, especially for those of us in the little old UK, surrounded by the giant economies of North America and the East, along with the turbulent uncertainty of the Eurozone.

very nicely summarised and explained – thanks

This is all interesting stuff but it misses a couple of very big questions.

Firstly how do you invest the safe (bond) proportion given the horrendously low yield (high risk) of UK bond markets right now.

A 70 year with 70% in Bonds would be taking a very high risk with their capital.

Answer. Don’t use rules of thumb – take account of market distortions, stay short (hold a good slug in cash deposits) despite low interest rates. or let a fund manager provide the mix of bonds for you.

The second big issue? – well that will be covered in my forthcoming book.

@Paul — The low yields are a big concern, but I don’t think it’s correct to say long-term investors are taking a big risk with their capital. As far as I’m aware, the yield to redemption of all but the very shortest Gilts is positive. You’ll get your money back after taking income into account unless the UK government defaults, and I can think of no circumstances in which it would be in its interest to do so.

The real risk is that you get return of capital, but basically no return *on* capital. That’s why as a pretty active investor I hold no gilts currently. I am happy to let cash and NS&I index-linked certificates add some safety ballast to my portfolio, albeit not with the benefits you’d expect from bonds in normal times (due to bond’s already tiny yields).

But anyway, this article is aimed at passive investors, and the whole point is with passive investing you don’t go around speculating and thinking you know better than the market. Exactly the same arguments about gilts you and I might make about bonds could have been made on January 1st 2011, and gilts returned double-digits from memory last year, and were the best performing asset class. Passive investors use rebalancing and strategic allocation as their weapons, not speculation about the market.

Finally, as I always say we can’t include everything in every article, hence all the little blue links. 🙂 Here’s a recent article on exactly the difficulty of investing in bonds right now.

Cheers!

Simon,

One of the best ways of getting geo-diversification is to invest in the little old UK (the LSE, that is). The ten biggest shares in a typical fund tracking the FTSE All-Share Index accounted for 35% of the total, it is even higher, 45%, in a FTSE100 tracker, and they are all major international players.

These companies only derive a relatively small part of their profits from within the UK, in some cases next to nothing.

The big ten are:

HSBC; Vodaphone; BP; Royal Dutch Shell A; GlaxSmithKline; Royal Dutch Shell B; British American Tobacco; Rio Tinto; BG Group and Diageo.

Thanks for the good post.

It seems sometimes that the passive / managed approaches are portrayed as completely polarized, when in reality many investor follow a mixture of the two.

I’m wondering if this could be considered in terms of an allocation, say 80% passive / 20% active, perhaps based on cost?

TA, From this article it sounds as though 30% plus losses are likely and even, from the NOOOOOOO! tabulation, that a 50% loss may have to be faced. The only people who have to face this are those who buy all their shares at the peak of a (massive) bubble and sell them all at the bottom of the following trough.

It reminds me of the Great Crash of 87. In October 87 the market plunged 34%…….end of capitalism as we know it!! The only people who lost 34% were those that bought on 5th Oct and sold on 9th Nov. In fact the market rose 19% over 1987 as a whole so long term investors had a pretty good year. Market flutuations are not the same as losses.

“Liked” 🙂

I am freshly retired at 55 (part choice, part health grounds) and I manage my own pension fund. I am about 20-25% cash, about 30% bonds / bond funds and the rest is equities. The question I asked myself is how soon will I need to tap the fund. We have some investment property that covers the monthly bills, some cash in hand and a portfolio of shares that provides dividend income and so I concluded that I probably would not need to tap the fund for 10 years at least. Now rental incomes could fall, the equities could crash, cut dividends etc but I feel there is enough breadth to keep us in a reasonable but by no means extravagant lifestyle. So I am not a great believer in the rule of thumb. My guess is that on most metrics I would be over-exposed to equities. But I feel pretty happy with the allocation. My biggest mistake when I started managing my pension fund was to over-diversify. I ended up with too many modest holdings that ranged from the ultra boring to the frankly (with hindsight) frivolous and imprudent. My portfolio has been heavily rationalized. It is now part passive part active but slowly moving more to the former. I have concluded that the critical thing is to have enough liquidity for your foreseeable needs plus a fair bit more. As I get closer to drawing down I will almost certainly create my own bond ladder and reduce equity exposure but it will depend on how the world looks at the time. I don’t see a magic formula.

To the investor.

As ever the answers depend upon personal circumstances.

Someone of 60 in a pension fund drawing down income needs a stable (ish) return. Drawing down heavily on a declining fund value risks extremely rapid capital erosion.

My point is simply that a 60/40 bond equity fund – whilst having produced lovely past performance during the last 30 years of bond bull market could well be at it’s minsky moment (turning point) . The short term value (from which withdrawals are taken) of long term bonds get’s savaged when inflation and interest rate expectations rise.

So hang on to a good slug of short term stuff and cash.

Don’t assume a mixed or tracking bond fund offers diversification safety relative to equities for the future.

Remember – in a crisis only one thing goes up – correlation.

57Andrew makes a good point.

If the end point is to draw down from a HYP type portfolio then it doesn’t make sense to have significant investment in low yielding bonds on the way to the target date.

I really nice summary of nearly everything you really need to know about asset allocation.

One think I learnt in 2008 was that my real appetite for risk in a plunging market was much less than I thought it would be in my imagination. I expect many investors particularly those within a decade of retirement might have found the same.

The rules of thumb about maximum equity allocations based on maximum sums you are prepared to lose in a crash are really helpful for older investors (who have less recovery time) I think.

Your article on the current dilemma about bond investing was also really informative. (Advice to avoid overly long bond durations and to consider cash and index-linked certificates where possible as part of the non-equity allocation)

Thanks!

@Paul — Sure, I get the danger in government bonds. As I say I have none. I’m just saying that (a) passive investors are *passive* investors. Duck and dive out of that and you’re something else — history suggests an under-performer. And (b) while it might be obvious that gilts are expensive, they could stay this way for decades (see Japan — I don’t expect it, but it’s possible).

Did you read the article I linked to? It explains that a rising rates environment isn’t as terrible as it seems even for bond funds, as they can roll into higher yielding securities as their existing holdings mature.

From the article I linked to: “According to Vanguard, the largest annual loss that a 100% UK bond portfolio would have suffered in the last 30 years is -6.27% (in 1994).”

That’s 100% bond portfolio — in reality, a mixed 60/40 portfolio would have equities likely to be doing a lot of heavy lifting to make up for the short-fall from the declining bond fund. Even if we assume this is the end of a 30-year bull market in bonds (still very much moot) I don’t see people’s bond funds being decimated as you’d see in an equity crash, more just extremely poor and mediocre.

Caution is warranted, granted, for those of us of an active bent, but clear diversification and perhaps a heavier allocation towards cash and the shorter end as you suggest is probably as far as a passive investor wants to go.

(A 60-year old drawing from a pension fund who is all-in bonds currently should probably annuitise and be done with it).

thx–great article

A quote from Warren Buffet in this year’s Berkshire Hathaway letter:

Today, a wry comment that Wall Streeter Shelby Cullom Davis made long ago seems

apt: “Bonds promoted as offering risk-free returns are now priced to deliver return-free risk.”

Bond fund performance over (or worst case period during) the last 30 year is not a very useful indicator for the future as it’s been pretty much a one way ride. Reducing interest rates and rising values of bonds.

A look back to the last big turning point upwards on bond yields – using Barclays Gilt Equity study – might be useful. Will do so when i have some time.

And watch out for Annuitisation idea – it’s is also a one way ride. Once it’s done it’s done. No reversing off that decision so be very careful it’s the right one before jumping especially right now as the rates are on the floor. (and buy the right type – if your health is bad get an enhanced annuity quote – take some advice)

Can the yield floor go for long UK bonds go lower?- e.g. Japan – Well I guess so I guess so but the risk must be that it jumps up from here. I’m just concerned that folk don’t view bonds and funds as safe havens as this turning point.

Things can get very messy when bond markets turn. Witness several European countries that used to have bond yields similar to Germany’s

> I found it next to impossible to actually imagine what a 50% loss would feel like,

It feels like a bastard. No fun at all. Been there, in the dot-com crash. With the benefit of hindsight, the training was worth every penny. It didn’t feel like it at the time, and it took nearly a decade to return to the fray.

Now I can tolerate the odd nearly 30% hit on occasional shares with equanimity, as long as they stay paying dividends, and I have seen the benefits of sitting tight and the 30% hit melts away over time.

It has to be said that some of the education on here has reduced the overall volatility of my portfolio to a lot less than the 30% 😉

I just had to look up that data on the UK bond index. Data from the world renowned Equity Gilt Study.

Worst 5 year period in last 50 years?

Not surprisingly – was 1971 to 1976.

Real (total return i.e. gross income reinvested a la pension or ISA) returns on the medium term bond index was . . . wait for it . . . .

Minus 10.7% per annum.

That’s a 43% real terms loss over the period.

The worst year ?

Yep you guessed it again – 1974 – the same year that the stock-market tanked. The bond index lost 40% in real terms.

Mind you back then there’s was loads of yield on gilts to soften the blow. So the loss was reduced to a modest 30% after income reinvested.

And the moral is?

Watch out about making any assumptions that UK or USA bonds are safe. Havens.

Short term individual gilts held to maturity fine

But managed funds of them – with loads of long duration bonds inside – Not on your nelly – not now.

Trust this helps

@Paul — Good stuff going back beyond 30 years; interesting. We agree much more than we disagree; I am just very wary of encouraging passive investors to start become active asset allocators as I think most people will do much worse once they begin playing that game. Maybe this bond call will prove sound or maybe not, but they then have to keep up their right calls for 30 to 40 years… The data suggests they can’t.

Hi,

I think you need to strip out the concepts of passive investing for low costs – which is fine – from asset allocation.

Even within both asset classes (equities and bonds) and whilst I accept perfect market timing is not possible – I do think it’s quite easy to avoid the “big tops” –and assume Mr Ermine would have liked to have known about this in 1999?

It’s also reasonably easy to guage when we’re somewhere close to a bottom – if not precisely at one.

Being close to a bottom should be nice experience – not a horrific one! But recognising a bottom is only possible once it’s walked past!!

“Boom Boom”

To keep things simple – when we have very little invested (compared to our lifelong goal) and we’re a long way from wanting our funds then a simple drip feed strategy is fine. And long only equities is better still. Ride the bumps because they just don’t matter – falls are all good news in the world of pound cost averaging.

But once we’ve accumulated a reasonable chunk of our goal (and whilst continuing to drip feed any new money – without much thought- into risky assets is fine) it also becomes paramount to consider how to protect what you’ve got.

Reverse pound cost averaging is ruddy dangerous.

Maybe we’ll have to agree to disagree on this but I hope you’ll add my book to your recommended list later this year.

Probably best that I get back to writing it now.

Paul

Some very interesting comments. Paul’s point about 30 years not being long enough to view potential bond volatility and his data from the Equity Gilt Study on the 1970’s are highly relevant. I’m old enough to remember that inflation as measured by RPI topped out at 26% in 1974 and there were rumours at that time of plans for a government take-over by ex-army officers to address the economic and political chaos!

Index-linked gilts were not available until the 1980’s: one can presumably assume that index-linked gilts would hold up comparatively well in a 1974 scenario. For people of retirement age where capital preservation and preservation of purchasing power are paramount, indexed-linked NSI certificates (when available) and index-linked gilts seem to me to be good core holdings. However, since neither pay commission to intermediaries and are therefore not aggressively sold, they have to be actively sought rather than acquired via “financial advisers”.

@ Elizabeth – I don’t think of my home as an investment – I’m always going to need somewhere to live. Other real estate holdings should be sliced out of your equity allocation.

@ Simon – You could look at the holdings of a developed world or all-world ETF or index fund as a good proxy for a global portfolio.

@ Webnibbler – Yep, plenty of people do this. Personally I use investment trusts to access the small-value equity sub-class because I can’t access it with passive funds. In this case, I use a low-cost IT and feed in a percentage of funds in line with my small-value allocation.

@ Paul – check out Ermine’s comment.

@ Paul C – Don’t think anyone in their right mind would declare any asset safe. Point is, if you’re long on equities and you want a low correlation asset that will reduce your risk if things get even worse (perfectly possible) then bonds are a reasonable bet. Is any strategy guaranteed? No. Will it work every time? No. Should you take into account the risks that affect your particular circumstances? Yep.

If I’m a 70-year old then I’m particularly vulnerable to inflation risk and duration risk. I absolutely agree with you that short-term maturities and plenty of cash to take care of living expenses would be high on my agenda. But if I’m 30 with 30 – 40 years to go and a high equity allocation, then no. I’d happily use long-term bonds to offset the possibility of deflation, knowing that reinvested income and rising yields will ‘smooth out the bumps’ as and when interest rates rise.

Agree though that rules of thumb are guidelines only, not think-free, get-out-of-jail free cards. As for ease of market timing, the bulk of the evidence suggests that most investors damage their returns by trying to market time.

As a strict passive investor I would normally be with the Investor on this. But the choice between short and long duration bonds at the moment is for me a question of risk management regarding wealth preservation, so I am with Paul. Elsewhere the current dilemma about bond duration in the context of historically low bond yields has been described in terms of Pascal’s wager. (An argument about the existence of God where the downside for the non-believer who is wrong is far worse than for the believer who is wrong!)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pascal's_Wager

In the current context the investor who goes for short duration bonds and gets it wrong (when yields fall) has lost a few points of yield . The investor who goes for long bonds and gets it wrong (when yields rise) will suffer much greater losses.

By the way there is a recent interesting conversation with William Bernstein on the bogleheads forum about this subject.

PS Previously missed the Accumulator’s comments and agree that investment horizon is relevant to appetite for longer duration bonds

@ Arch and Adrian – interesting points both and well worth thinking about. The Boglehead rule of thumb for allocating between nominal and index-linked bonds is to go 50:50.

Pascal’s wager is much beloved of Bernstein, as I recall, and he’s definitely in favour of short-term bonds. Do you have a link to that forum discussion?

Here is the link

http://www.bogleheads.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=75060

The relevant comments are quite a long wasy down around 20-21 May.

I have always liked his definition of bond duration as the ‘point of indifference’ by which I think he means the time by which the sum originally invested in a bond / bond fund will have been returned to the investor as yield.

I don’t have any bonds and I don’t understand them! Practically everything is in equities paying good dividends. There’s a few bob scattered around bank accounts in fixed rate accounts but that’s only to de-lumpify the drip feed into more equities.

I’ve become a bit of an equities believer (and it is faith rather than knowledge) and I simply see it hard to find other asset classes which will, over the long run, deliver an income directly coupled to economic growth[1]. (Property is too much like hard work to own – though I am investigating REITs).

[1] possible dangerous assumption of continued growth in that sentence.

@ Adrain – thanks for the link. Will take a look at that tonight.

@ Paul – re Warren Buffet letter – it’s a great quote that highlights as much as anything the wrong-headed notion that an asset can be defined as risk-free. Even the cash in my bank account is being silently nibbled away by the moths of inflation. The Sage also mentions in that letter that Berkshire Hathaway maintain large liquid positions.

@Adrian — Interesting thread. The comments from ‘Matt’ are relevant, I feel. If we enter a deflationary period, long-term bond yields will very likely fall further — yields in Japan fell from 3% to 1%. That’s a huge capital gain for long-term bond yields, and anyone only holding short stuff would face either rolling it into lower long-term bond yields or staying in short duration / cash for the foreseeable, which has turned out to be decades in Japan.

Worse, deflation is bad for equities, so you’d see that part of your portfolio fall, perhaps precipitously, too, in that scenario. In contrast, in an environment where long-term bond yields start to reverse, bond funds with longer-duration will likely fall (though as discussed if you hold individual long bonds to maturity you *will* see return of capital) but that will very likely be dwarfed by a steep rally in equities, since it would presumably coincide with economic recovery and a resolution of the fear and dread (Europe, government debt etc) that has taken long-term bond yields down to these low levels.

I stress again, on a personal level deflation/long gilts is *not* my bet. I’m a pretty active investor, and I have no long-term government bonds as I type. I am with that camp when it comes to where I place my chips. Thus it’s a bit ironic to be defending asset allocation that has a long-term bond component.

But I stand by my comments that passive investors following a portfolio approach are probably best off sticking with their allocations, and not trying to call markets that are *not* obvious or one way bets, whatever any of us think is likeliest.

If the bond component falls in value a bit over a few years (which as I say I happen to agree is the most likely outcome), that has to be seen in context of how the overall passive portfolio performs — the idea is *not* to punt on the best asset class every year, it’s to get an overall satisfactory return.

I would point out what sort of job you have matters a lot:

University lecturer = bond-like job: have more equities

Salesman on commission = equities-like job: have more bonds

http://canadiancouchpotato.com/2011/07/07/holding-your-bond-fund-for-the-duration/

@investor. I completely agree with you that it is dangerous and wealth destroying to take try to predict or to take bets on the market. I also agree that a deflationary environment is possible, as of course is a few years of high inflation (Like you I know I can’t know the direction of the market). For anyone with a long investment horizon, on this basis, I would agree that the best strategy, even now, is to buy bond index ETF / mutual fund (current weighted duration of the UK gilts market is around 9.6).

The link above which you may have seen is reassuring and contains some interesting data on historical returns on US & Canadian long-term bonds (see ‘And the bond played on’ – where it seems that an annual double digit fall has been a very rare event).

For all that if I was a newly retired investor with only a medium-term investment horizon I would argue (on risk management / Pascal’s wager grounds) that it currently makes sense to keep your bond duration shorter than the market average of 9.6. You could use iShares 0-5 year gilts ETF (although current YTM is only around 0.5%) or as I would you could mainly follow the recent discussions / advice to use cash as a substantial part of the non-equity portfolio.

Incidentally, I think the dictinction between making decisions on a risk management basis vs ‘knowing better than the market’ approach is crucial. Although both involve adopting a non-market average portfolio the justification for doing this is very different and they are pretty much opposites. In the latter an investor claims (foolishly nearly always) to have better knowledge than the market. In the former the logic is ‘I know I can’t time or predict the market, but what I do know is that for my personal circumstances the risks of changes in the market are asymmetrical’. ie the downside risk of the market moving sharply in one direction (in the case of the current discussion regarding bonds if yields rise) is much worse than a market move in the other direction.

@ Greg

The point you make about job security being a factor is very good one, but….

Are there really many “bond like” jobs in the UK at the moment?

The public sector headcount will shrink c. 20% in the next 5 years under current government plans (and out of date optimistic government revenue forecasts)…

…the only real “bond like” job I can think of are under-takers 🙂

@TA. Buffet’s liquidity is, as he says, mostly in Treasurty Bills which are, essentially 1yr bonds.

Although not to many people’s taste the Permanent Portfolio asset allocation;

http://monevator.com/9-lazy-portfolios-for-uk-passive-investors-2010/

is worth picking apart to see how a portfolio containing very volatile but uncorrelated assets perform to give fairly steady growth through different conditions.

A couple of things that I picked up from Harry Browne’s thinking are that

* you’re not holding long term Gilts for their yield

* cash is an important asset, not just an “opportunity cost”

* you need tight, concise rebalancing rules

There’s also a whole load of thinking about how to hold your assets that’s worth consideration whatever your chosen allocation.

When I was floundering about trying find out about asset allocation I found this comparison of the major (US I’m afraid) asset allocation strategies quite useful.

http://madmoneymachine.com/2012/02/28/lazy-portfolio-analysis/

By far the most illuminating experience wrt. asset allocation I had was holding an advisor managed, equity heavy, “balanced” portfolio, with cash in an Icelandic bank in 2008. Happy days 🙂

@ Adrian – thanks for drawing attention to this thread:

http://www.bogleheads.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=75060

Fantastic stuff. I’ve even ignored Spain v Portugal to get through it. I thoroughly recommend this thread to anyone who’s interested in how to handle their bond allocation in these extraordinary financial times.

Great topic & comment thread.

Perhaps I can offer a different perspective? My own financial enlightenment was to realise that ultimately I was saving/investing primarily to provide an income in retirement – so therefore why not develop a portfolio that provides an income? I also realised that there are several ‘layers’ of income that can be bought, with different risk characteristics. So the equities/bonds allocation is too simplistic.

My main asset classes are: property (family home – avoiding housing costs in later life), pension fund (through work) and financial assets – in the ratio of approximately 1/3 each. The financial assets include 3 main asset classes: cash/cash deposits, dividend shares, and fixed-income assets (such as gilts/government bonds, corporate bonds, PIBS and others) – in a ratio of around 1/3 each.

However, within each of the financial asset classes there is clearly a spectrum of risk: again, for dividend shares and fixed-income assets I aim for a split between low/medium/high risk holdings.

Obviously, you can’t start with this overall portfolio but I suggest it as a potential target allocation – in other words, the end-game of your investing career.

@ Moneyman – thanks for your contribution. You’re right that discussion of an equities / bonds split is quite a low-res view of asset allocation. You can certainly zoom in for more detail.

For me that would mean:

Equities – broad market index, small-cap and value. Property and commodities allocations would also be carved out of equities although not my house. That’s not an investment, that’s a roof over my head.

Fixed income / defensive assets – gilts, NS&I Certs and cash. Gilts break down into short-term bonds, long-term, intermediates and index-linked (i.e. anti-inflation).

These are the assets that I both understand and have a useful function to perform in my portfolio. I try to consider all investment sources as part of one portfolio i.e. ISA holdings, pension holdings and regular holdings are all considered part of the same whole – at least as far as my retirement plans are concerned. Rainy day fund and mortgage fund are considered separately as time horizon is different.

The point The Accumulator makes about viewing ISAs and pension/ SIPP as part of one portfolio is interesting, my tax situation makes SIPP contributions much more efficient, but wanting to maintain a large cash position (earning 0%) is difficult in a SIPP. Hence while I continue to drip feed into equity funds in my SIPP I may gradually liquidate my stocks and shares ISA and shift that money into Cash ISAs instead.

My current SIPP positioning is 50% cash, 25% index linked gilts and 25% cash that is waiting for a correction before topping up equity index funds.

I’d feel happier about having 75% in equities within my SIPP if my Cash ISA pot was bigger.

I’m with Paul C on conventional gilts, although they may have one last hurrah if we have a sharp correction in the next 6 months or so.

Oops, that should have read “My current SIPP positioning is 50% equities”.

@SemiPassive — Our recent guest article in praise of cash by Pete Comely had a link to some interesting SIPP-able deposit accounts:

http://www.investmentsense.co.uk/free-services/best-buy-savings-accounts/accounts-for-pensions/

I’m not sure of the mechanics of using them, having never done so myself, but the rates there are seemingly much better than the 0% you’re getting so worth investigating perhaps if you’re keen on holding a big slug of cash in your pension.

Thanks for the link, once you can get 3.5%-4% (eg keep up with inflation or the dividend yield of the FTSE100) it becomes more viable to hold cash. Although my SIPP provider doesn’t offer access to those accounts and I wonder whether there is tax to pay on the interest or are those gross figures like Cash ISAs where you get to keep the lot regardless of your oncome tax band.

On the ‘traditional’ age related move to increasing bond allocation, as with another poster my current aim to beat inflation (avoiding level or inflation linked annuities which are appalling value)

will be to use income drawdown based on a SIPP full of higher than average yield shares.

To Semi Passive

You could well be right about the last hurrah on mid and longer term gilts but I wouldn’t place money on it myself. A shift up in inflation expectation or a shift down in the UK’s rating could knock these securities for six.

Interesting to see you hold a fair % in linkers and I’d be careful there too. In his book – “The Trouble with markets” Roger Bootle (one of the more intelligent economic forecasters) offers well reasoned argument of the risks with these assets in the event that we do flip into the dreaded deflation. I’ll try to summarise:

Gilts and Linkers are priced according to a discount rate for valuing future cash flows. That rate is normally linked to inflation at say RPI plus 1% pa which makes linkers fairly stable in price during most “normal range” periods of inflation.

However, if we slide into deflation the discount rate for pricing these securities is forced up. Why? Because it cannot go below zero at the short end where cash gives a minimum zero return.

So, if the expected rate of inflation (deflation) fell to say -3% on a 5 year outlook we might have a discount rate of +3% pa over that period. Giving a nominal expected return of 0%.

The rising discount rate – which might be less prominent further down the yield curve – would nonetheless rise at most durations reducing the present value of future cash flows. In other words prices would fall.

To quote Bootle – “this quirk complicates indexed bonds. Many people expect them to be safe and predictable instruments throughout their life and not only if held to maturity. This they are NOT – if the economy flips into deflation.

I wouldn’t say hold none as we all need to hedge against inflation (as well as deflation) but I hope this helps.

Should have read

“if the expected rate of inflation (deflation) fell to say -3% on a 5 year outlook we might have a discount rate of RPI +3% pa over that period. Giving a nominal expected return of 0%”

@semipassive

I am not sure if this is right but another way of explaining price movements of index-linked gilts is I think as follows.

The price of linkers is determined by market expectations of inflation. If the market expects high inflation the price of the linkers is high. If the market expects lower inflation or even deflation then the price of linkers falls.

Now consider the following scenarios:

(1) A short-term investor who invests in a single index linked gilt. The gilt is sold before maturity. The investor buys at high inflation expectations and sells at low inflation or even deflation expectations. The price is high at the time of purchase and low at the time of sale and the investor gets badly stung. This the concern in your post.

(2) A longer term investor buys a single index linked gilt and holds it to maturity. The investor buys at a price expecting 2% inflation but over the remaining term of the gilt there is 5% deflation. The investor will clearly loses out but not necessarily by very much in REAL terms. Even if the nominal sum returned is less than the nominal sum invested, the point is that in a deflationary environment the real value of the sum returned will be to some extent protected. (Suppose the investment is £100 and £90 is returned. The £90 post-deflation will buy almost as many goods as £100 pre-deflation.)

(3) A long term passive investor who buys different linkers at different time points and holds them to maturity. Sometimes the investor will be lucky and real inflation will be higher than the market expectation of inflation at the time of purchase. Sometimes the investor will be unlucky and real inflation will be less than the market expectation at the time of purchase. However, on the average over the medium term the investor’s luck will balance out and the investor will get protection from EXPECTED inflation.

Most importantly though , in all three scenarios the investor gets protection from UNEXPECTED inflation. Only in scenario 1 does the investor (more a gambler than an investor in this scenario) risk a serious erosion of wealth in return for buying this protection. To my mind the point of investing in linkers is as a hedge against UNEXPECTED inflation and in sensible scenarios (ie 2 and 3 above) there is only a low risk of significant loss of purchasing power.

I should say that I am very much an amateur self-taught investor and I would appreciate comments about scenario 2 particularly any proper quantative analysis.

All the best

Adrian

The post should have been to @paulclaireaux too!

@paulclaireaux @semipassive

http://www.fixedincomeinvestor.co.uk/x/learnaboutbonds.html?id=206

You are probably familiar with info in the above link and similar information on the debt management office site but it confirms what I thought.

If index linked certificates are bought at par then you can’t lose purchasing power even with deflation provided they are held to maturity.

If you buy at a price different from par then you may gain (if actual inflation is worse than the priced-in expected inflation). Or you may lose (if actual inflation is better than the priced-in expected inflation).

However, if you buy index-linked gilts of different durations at different times (eg pound cost average with an index-linked gilt index fund) then the times you lose by buying at non-par will be balanced by the times you win.

So, for the investor in the draw-down period (eg a retiree) index linked gilts offer guarantee of purchasing power with the added benefit of protection against high unexpected inflation. There are two main costs for these benefits. The first is to lose out on actual gains in value and purchasing power from ‘normal’ bonds during deflation . The second is to lose out on the equity risk premium.

Anyway for me as I approach the wealth preservation / drawing down period it makes sense to have a significant proportion of my bonds in linkers. I have a small proportion of gilts but otherwise I am very close to semi-passive’s 50% equities 25 % index-linked and 25% cash.

A

I meant index linked bonds not certificates!

To Adrian.

I wouldnt question your arguments but I’d prefer not to buy linkers to hold to maturity. The consolation that linkers maintain purchasing in a deflationary spiral does not sound like fun.

Protection from deflation can be had with cash and short gilts which also offer the option of selling out to buy the stuff that get’s really cheap in deflationary times – equities or property.

Also – as Credit Suisse note in their last yearly report – Gold performs best of all during times of both high inflation and high deflation.

I’ve reduced my Gold holdings of late but still retain a fair proportion in that assets class just in case fear of mass soverign default takes hold again. That credit risk is also something we need to factor in to pricing of Gilts and Linkers.

Tricky business investing eh !

I wasn’t meaning to imply that linkers are the investment of choice in deflation just that even in the worst case deflationary scenario they should largely maintain purchasing power or real value despite showing a nominal fall. Cash and ‘normal’ nominal bonds are as you say clearly going to be better in deflation. For me the answer over the long term is too hold a bit of all three ie cash, nominal bonds and index linked bonds.

We’ll have to disagree about gold!

I am setting up my portfolio as well as my wifes all wrapped in an ISA, until we can hopefully meet our ISA allocation and also tuck some more into SIPPs

We do not have the exact same asset allocation. Should these be viewed as 2 separate entities or should they be seen as a holistic portfolio in order to get a clearer idea of how close we may be to our goals. We are the same age and have the same goals (she just doesn’t know it yet) so there’s nothing too complicated there. What are the ‘rules’ about managing two or more portfolios?

@ emanon – if your goals are the same then it’s best to treat your combined assets as one portfolio for the very reason that you suggest and so you can maximise the opportunities of any tax shelters.

@all — I’ve slightly tweaked and republished this post as of 12 November 2019, in order to fill a @TA-sized hole. (He’s been doing a second edit of our long-awaited book!)

Anyway, just a reminder that reader comments prior to this one from me may refer to market conditions from earlier years. 🙂

I recently came across the idea of relating bond allocation to yield. This makes a lot of sense to me. May be worth adding the concept to this post.

See:

https://www.financialsamurai.com/suggested-stock-allocation-by-bond-yield-for-logical-investors/

Hi

I’m intrigued that both Tim Hale and Larry Swedroe (at least his first approach above) appear to suggest that you have no money in equities at all once you retire. Is that a correct interpretation of their approaches?

@Matt (54)

I too was puzzled by this.

I suppose that the theory goes something like – “If I have sufficient money to retire, and bonds provide sufficient inflation protection (perhaps not entire inflation protection, but near enough) , then why risk anything by being invested in equities?” If you’ve won the game, why risk anything?

But have a look at https://www.forbes.com/sites/wadepfau/2017/05/04/the-pros-and-cons-of-rising-equity-glide-paths-in-retirement/#8252edf343dc.

@TI – thanks for reviving this thread. As a paragon, I’ve just re-read the old comments. Fascinating!

Many were about the relative benefits of holding long duration/short duration bonds. How did that work out over the last 7 (!!!) years?

I’m also confused by investing timeframes and retirement. If I’m retiring in 10 years, is that my timeframe? I may live another 40 years, in which case is that my timeframe? Or is it halfway between them? (assuming my portfolio is divided into equal size pieces for each year…)

To be honest I’ve gone for the Markowitz ‘can’t decide so let’s go 50/50’ approach.

@The Borderer @Matt

Hale is talking about shorter term targets like saving for a house deposit, education fees etc.

Asset allocation during de-accumulation is another, albeit related, topic.

This is a great article, thanks.

I especially like the: The Larry Swedroe ‘NOOOOOOOO!’ rule of thumb. Not that I know when (or if) it will happen, but I think a lot of investors (including myself) who weren’t there, or didn’t have much at stake, in 2008 may get a big shock in future as they’re not used to things going down.

@Fremantle. Yes, you’re right, I didn’t read the Hale section properly. Thank you

I believe rules of thumb for asset allocation linked to age are fundamentally misguided. This is not simply an academic exercise, I’ve been an investor since the 1980s, hence lived through several major depressions, and now live off my investments.

Let’s start with three assumptions.

1) If there is a total market failure it will not make a difference whether you’re reliant on shares, gilts, cash or a final salary pension scheme. Everyone will be broke and we’ll all be faced with starting from scratch. Think how your asset allocation strategy would have worked in Viemar Germany. Such corner cases require very different strategies.

2) I’m assuming that in the absence of such extremes as hyper-inflation that shares will outperform other assets over the long term, which I take as meaning decades. While this has generally been true in our lifetime there have been many periods in history where gilts were the go-to investment. This was certainly true prior to world war one and if you think we are in another such era then don’t buy shares.

3) You can’t time the market. Not totally true, but in general a market trend can out-last almost any ones convictions. You can have an idea of whether the market is over-valued but it is very hard to know when the chickens will come home to roost.

Given these assumptions what I’m looking for is a strategy to cope with periodic slumps in the stock market. In other words I want to avoid being a forced seller of shares. But once I’ve achieved this all other assets should be invested in shares. So the question then becomes how much money do I need and this partly depends on your current circumstances. In my case I’m living off income from shares, as opposed to using capital gains. If I take as my assumption that dividends may fall by 50% for as much as ten years then I may need the equivalent of five years spending in safe assets such as cash or index linked gilts.

If I relied on selling shares to generate an income then I might want enough cash to cover all my spending until the market recovered, so possibly ten years spending in safe assets. This realisation naturally drives me to having a preference for quality income stocks as it allows more allocation to shares. Worth considering when people say you can generate your income by selling shares rather than relying on dividends.

If you’re still working then you are looking at totally different set of risks, principally how long you might take to find a new job if you were made unemployed during a recession. Conversely you might want to consider how much you would be willing to cut back on spending during such difficult periods, for example no foreign holidays, or even sell your car. Or look at other sources of income such as renting a room in your house, or even renting out your entire house and going travelling.

However the key point is that your allocation to investments other than shares is an absolute amount rather than a percentage. Indeed as I get older, and my savings continue to grow this amount is actually a decreasing percentage of my total wealth.

@Freemantle (58)

Re-reading, you’re right, it’s more about fixed expenditure aims (college fees &etc).

However, the case for 100 % ‘risk free’ investment in de-accumulation is seriously worth considering.

True, your ‘legacy’ will be diminished, but if you don’t need to care about a legacy, then what’s to gain by taking any kind of risk?

In a perfect world, if the sum of negative cashflows (i.e. annual expenditure in an assumed retirement lifespan adjusted for inflation) is equal to the present value of your investment pot, and that the pot is invested in a totally risk free investment (building society, or several bs to encompass FCA protection) that will return more than required, why then invest?

As I say earlier, you’ve won, so stop.

Unless, of course, a morgan plus 8 speedster is on your bucket list!

On risk-free/zero equities… I’m not really one for traditional/US/@TA-style plan-to-spend-it-all de-accumulation, but as I understand it a new theory has emerged in recent years (possibly via Wade Pfau, from memory?) that you run your equities right down in the window before retirement, and then you start to add equities again post-retirement. (Maybe not down to zero, but a long way down. And then, as I say, you ramp up risky assets as you age post-retirement).

I believe the idea is to avoid sequence of returns risk when you’re most vulnerable to it (about to retire, the longest ‘retirement horizon’ you’ll have). Owning more equities as you age might seem counter-intuitive (more risk) but people forget other risks diminish (specifically longevity goes down, and you also tend to spend less as you age.)

From memory it was backed up by a bit of

data miningmodeling.I’m in the live off your natural income brigade, of course, and find all this dancing on a pinhead modeling de-accumulation and SWRs unconvincing, but reasonable people can definitely differ on this! 🙂

On subject of natural income, de-accumulation, SWRs etc. is there any way that such relevant articles could be grouped? A bit like the Investing->Passive Investing tabs? I try and aggregate them via judiciously chosen search terms, but may well be missing some. Would be great if they were categorised/listed in some way via a heading? You might imagine someone just wanting to work there way through the whole income (both natural and total return) back catalog say 😉

@Mike Benjamin – I fear you may be double (or half) counting here. You compare living off dividends with selling down shares and state “If I relied on selling shares to generate an income then I might want enough cash to cover all my spending until the market recovered.”

But in your example you’re expecting to sell some shares (or units) anyway. If the market dives 50%, you just sell less – 50% – and top up with the cash for the other 50%. So your cash bucket is exactly the same.

@Mike Benjamin – although I agree fully with your point about Weimar-style collapse or hyperinflation. I’m only interested in the risks I can meaningfully mitigate and in South London that precludes guns and stockpiling food.

@TI (64)

Is this what you recollect?

https://www.kitces.com/blog/should-equity-exposure-decrease-in-retirement-or-is-a-rising-equity-glidepath-actually-better/

@The Borderer — Hi. Not sure. I think that it’s referencing the same research, and I probably did read that article, too, but I do seem to remember a really low equity allocation at retirement as being more prominent. I’ve read several articles about this, there were a spate of them in Weekend Readings a few years ago. 🙂

For the benefit of other readers, the article you’ve referenced doesn’t talk about low/no equities at retirement per se (then again maybe I made that bit up!?) but it does make the case for increasing equities throughout retirement:

@TI (69)

Yes, but I believe that the fundamental problem with this idea is “…clients will dollar cost average into markets at cheaper and cheaper valuations”. In retirement clients will not, generally, be investing new money into anything at any level that could possibly influence their portfolio. Unless the concept is that they are selling down bonds and reinvesting into equity.

I’m not sure I have the faith to do that.

This would be the idea, yes. You’d rebalance away from bonds and into equities. Remember as always these moves would be slow, and over time.

Not particularly advocating the theory!

I’m no where near retirement, but if my aim say was to secure a £30,000 income and ignoring the state pension, I’d look at an annuity for about 50-60% of it and de-accumulation for the rest.

Securing your capital as you approach retirement through de-risking makes sense, but then reversing it through equity exposure also makes sense. New money could come from whatever pittance the state pension becomes, but done in a way that reduces your need to de-accumulate your sheltered pension assets. I suspect converting to income class investments will throw some of the cash for income off, but I’ll also draw down on capital as required.

In respect of asset allocation in retirement I like the idea of a previous poster that the safe allocation should be an amount related to living costs rather than a %

I understand the appeal of annuities as a foundation of retirement income. I’m not a fan of annuities (it’s a black box investment, no transparency, Life Companies have a poor record here, you can safely assume there are substantial charges/expenses built in to the model)

I am surprised that one does not see longevity annuities (not uncommon in US) plan to deaccumulate and you survive to say 90 then an insurance annuity kicks in.

Pfau did float the idea of a minimum equity allocation at retirement then increase it. Backtesting showed that sequence risk in the first decade after retirement was the biggest contributor to the risk of poor long term outcome in a maximum safe withdrawal rate sense. He was a bit equivocal about it. Since all long term periods in the data set show equities giving the best returns if you just hang in there, then it’s not surprising that equities always get the starring role.

Decumulation is the issue and I think the best approach is to sort out your cash flow requirements and make sure these are covered by income and bonds for the first 10 years. Since I transferred a dB scheme into a sipp, and one big reason was to give my future widow a better income ( all the other bits of pension either cease or reduce to 50%), this is a long term strategy ( comes into effect post my death at the age of 116) so I am investing the sipp rather more heavily into equities than commonly advised ( 60% is the target).

The ISAs are much more conservatively invested as this is where any significant cash call will fall.

@HariSeldon – I rather think you’re giving annuities a bad press here.

Hopefully TDM will be along to give his expert opinion, but to my knowledge no annuity company has ever failed and no annuity has ever failed to pay out. I think the margins on annuities are very slim and so many big providers have left the market. It’s also a heavily regulated product with some guarantees from the state. As an INSURANCE product, it’s not a bad bet. How transparent is your home insurance?

After the last 10 years boom in all asset prices, I think an equivalent decade long slump in equity returns while all the QE money is bled from the system might change a few people’s opinions. My approach is “floor and upside” – secure your basic expenses and, when you want to or the market allows, withdraw from your risk portion for the extras.

All these rules of thumb seem to be applicable only if you are buying an annuity, and not if you intend living off the natural yield of your portfolio.

Re: The Borderers comment, the trouble is bonds – or at least gilts – don’t provide anything like inflation protection in our near zero rate world. GBP-denominated corporate bonds just about keep up with inflation, but if you are taking the full yield as income then that already puny 2% income isn’t going to keep up with inflation.

I can’t see me ever dropping below around 50-55% in equities, and that doesn’t mean all the rest will be in gilts but more likely a mix of commercial property REITs, infrastructure trusts and bonds of corporate, EM and high yield flavours.

I might have just 10-15% or so in cash and short dated gilts put aside to cover periods when dividends on all my other investments are cut, and can’t see that changing drastically unless gilt yields ever return to historical norms where they were higher than inflation.

@ The Investor – you’re (probably) thinking of rising equity glidepaths or the bond tent:

https://www.kitces.com/blog/managing-portfolio-size-effect-with-bond-tent-in-retirement-red-zone/

Cut equity allocation 5 t0 10 years before retirement, allow them to bob back up again (by spending down your bonds) in the years after.

ERN did a deep dive into rising equity glidepaths here:

https://earlyretirementnow.com/2017/09/20/the-ultimate-guide-to-safe-withdrawal-rates-part-20-more-thoughts-on-equity-glidepaths/

So many caveats it’s unbelievable. Bottom line:

Rising equity glidepaths helped a bit when equity markets were richly valued (as they are now) and you suffered a bear market in the sequence of return risk danger zone after retirement. In other words, they helped in exactly the situation you’d want them to, but not by as much as you’d hope, and in all other circumstances you were better off with a static allocation.

Much depends on the returns data you use plus a bucketload of other assumptions.

@ Vanguardfan – re: timeframe – depends. As others have said, Tim Hale and Larry’s Punching rule of thumb are for objectives with a definitive end point i.e. not retirement.

For objectives with a definite but uncertain end point i.e. retirement then I consider my lifespan (and Mrs Accumulator’s) as our time horizon.

The Markowitz / 100 minus your age / and Larry Noooo rule of thumbs all enable you to manage risk without reference to a definite time horizon.

@Hariseldon – I disagree with your dim view of annuities. The research I’ve read has convinced me that they are the best tool available for managing an uncertain lifespan. The longer you live, the better the deal as mortality credits pile up in your favour. In other words, the cheaper it is to finance your super-genes at the expense of mortals who fall at earlier fences.

Obvs, it wouldn’t help if the insurance company went bust but you’d be covered for 90% by the FSCS compensation scheme – which is much more generous than the investor compensation scheme.

You can lower costs by shopping around and negotiating – as I did for my mum. Don’t load up on expensive features, stick to vanilla products and go for inflation-linked if you possibly can.

I’m almost certainly going to buy an annuity once I get into the optimum zone around age 70-75).

The major problem with annuities is the bad press and the psychological hurdle of handing over your loot while focussing on the wrong problem (might get knocked over by a bus tomorrow versus I might live to be 100).

@ Brod – long duration bonds won vs short duration hands down in retrospect but I wouldn’t have fancied the risk.

I’m just wondering what the thought is to investing in countries with low CAPE ratio’s? Are they actually any ETFs/Funds out there which do this? That will hold the index’s of countries with CAPE ratio’s below a certain threshold and then swap them out once they hit a certain threshold for a lower valued country’s stock market index?

Giving it some thought but it would only be as a small part of my portfolio.

Hi AJP, the closest thing is a Global Value ETF. iShares and Vanguard both have one.

I’m currently grappling this so well timed, thank you.

I see my portfolio in 2 parts – DC pension which is 12 years away if current rules stay the same for drawdown at 57, and my “runway” to getting there (and could be FI in around a year, so 11 years runway).

Pension is all world equities on the basis it’s 12 years away…. Will rebalance a little but the 11 year runway is perplexing me as I expect to pretty much burn through that. Would be v grateful to hear how anyone else deals with this!!

Excellent update. Thanks @TA. I’d forgotten this gem from 2012. There’s so much superb content from the Monevator archives and it’s great to see it being updated over time 🙂

I’d also forgotten (as I must have read it back in 2012) the framing around % of goal achieved versus % allocated to equities.

That’s a neat perspective on the issue. Possibly better than the equity % = 100 (+/- risk tolerance adjustment) minus age type of approaches.

I’ve been dialling down equity exposure for the first time as I hit 50 now. I’d been running with the (close to) 100% crowd (and for a long time).

Diversification doesn’t come naturally.

The problem with diversification is there’s always something lagging in the portfolio. Equally, there should mostly be (at least) something going up.

I know we get put on the naughty step for active/dynamic asset allocation here @Monevator ( 😉 ), but, whilst it’s true (channelling Mae West) that too much of a good thing (passive investing) can be wonderful, I think it’s also equally true that if you’re going to sin (active asset allocation) then sin just a little bit (I think that phrase may have originated with Cliff Asness of AQR, on the subject of market timing, perhaps riffing off of Martin Luther’s ‘if you’re going to sin, then sin boldly, and repent’).

I’m now constantly adjusting a percent or two here and there between say gold and commodities or commodities and SCV; rebalancing from recent winners into losers and, occasionally, not doing that and just letting the (temporary) ‘winners’ run.

Don’t think it’s made much difference so far, but, if it screws up, then it screws up in a small way, and not as a big disaster.

Increasingly thinking that the ‘risk off’ side of diversification is harder than the risk on.

The first comment was the best and yours is no answer: “I don’t think of my home as an investment – I’m always going to need somewhere to live”.

You go ga-ga and your wife needs to do equity release to pay for your care. Then it’s an investment, eh?

She goes ga-ga and your children need to sell the house to pay for her care. Again it’s an investment, eh?

I know that our own wealth is dominated by the estimated value of our house. I am aware that it may well provide the capital that will allow my widow to live and then die in some comfort and security. Yet it is a “risk asset”. Why would I add to the risk by buying a pile of equities?

Things might be different if it were possible to buy “Care Insurance” but apparently nobody has found a way to make a living by selling it.

I feel like you updated this just for me!!

Another little twist

Are you an “optimiser” or a “satisficer”-a reference in a Humble Dollar post to an article by Christine Benz of Morningstar on 27 Oct 2025

Do you want to keep adjusting your Asset Allocation for “best” results or do you want to set your Asset Allocation -leave well alone and concentrate on on other things?

Personally always been a “satisficer” with an Asset Allocation that hasn’t varied much over 23+ years of retirement -initially 30/70 currently 35/65

All very personal and very dependent on investors particular circumstances

xxd09

@KTB – I’m not entirely sure I’m following but I held the six year income gap between retiring and pension access in cash and index-saving certificates. I think a ladder of individual index-linked gilts is a good choice, too: https://monevator.com/index-linked-gilt-ladder/

@DH – % of goal achieved is new – to this article anyway. I agree with you on sinning a little. Saints are in short supply 😉

@dearieme – you’re wading into comments written in 2012? Remarkable. I do think of my home as a disposable asset these days – TI convinced me with a great article he wrote many moons ago. Doesn’t stop me investing in equities though. Diversification and all that.

Do you seriously not own equities because you’re a homeowner? On the other side of the risk coin, do you factor in any future pension claims on your balance sheet? For example, State Pension and any DC pensions?

@cm258 – I hoped it would come in handy 🙂

A very timely update, thank you very much.

I have been following Monevator and Simple living in Somerset since 2013. I have not posted very often, just a thank you when something I read has been very helpful. Although I read all the posts, most of the excellent content goes over my head.

I have just turned 71 and have been looking at my asset allocation. The current breakdown after some recent adjustments is Cash 20%, Equities 27% and Bonds/Others 53%. The “others” are funds held as part of a Royal London Governed Portfolio drawdown pension.

Have always been in the 20% tax band and still cannot believe how I have accumulated my current asset total. I have made a few mistakes, moved S&S ISA’s to Fixed Cash ISA’s a little earlier than I should, and having worked with Nvidia some years ago missed the massive share rise. That gave me a few restless nights until my wife told me to get over it!

With the forthcoming changes to IHT and pensions, I am pleased I have been gifting from income over the last 3 years and is something I will continue to do. I think I have finally got to a point where I no longer need to try and maximise my returns but start to feel happy and content with what I have achieved and enjoy the spending and gifting in the years ahead.

I will of course keep reading the articles!

@TA

“I held the six year income gap between retiring and pension access in cash and index-saving certificates. I think a ladder of individual index-linked gilts is a good choice”

I take it this was at the point of retiring? What did this look like as you were running up to this point and still earning? Were you investing into the bridge with contributions only or did you skew it either way?

I can see a case for both being defense heavy on the approach or remaining largely risk on.

“Do you seriously not own equities because you’re a homeowner?”

Because we own the house I seriously don’t own 60% equities. But also because of time’s wingèd chariot. I can’t expect a Long Term in which collapsed investments could recover.

“Do you factor in any future pension claims on your balance sheet? For example, State Pension and any DC pensions?”

We have a couple of fragments of DC pensions left. The smaller we expect to empty over this tax year and next. The other I might hang on to in case I die before 05/04/27 in which case it could pass free of IHT to the grandchildren. If I surprised my little world by surviving past 05/04/27 I’d be tempted to buy an index-linked annuity with a 100% widow’s benefit. But I have more than a year in which to reflect on that notion.

I’m with those like Paul calling out that the whole equities Vs bonds split thing is misleading and dangerous.

There always needs to be the warning that bond are not cash unless held to maturity and bond funds are not cash nor bonds.

I soaked up years worth of asset allocation info and was then burned in 2022 because this distinction was typically not made.

It seems like we’re forgetting the lesson very quickly and going back to the same dangerous generalist.

Keep it simple – at age 64 – drawdown is a year or two away for me. I can sleep at night with just 3 funds in my Vanguard pension. I have enough… so I keep 3 funds LS 60, LS 40 and the Vanguard money market fund. The pension has an overall equity allocation of 50% equities split between the two Lifestrategy 60 and 40 funds. I keep 2-3 years worth of living expenses in the money market fund. There’s no point in being greedy. Enjoy your life, enjoy spending and sleep well at night.

@Hal – cheers! I’m ever so glad things have worked out for you. I know a few others in a similar position who are suddenly looking back and realising they are OK. I’m not sure if I’ve ever written a post on all the mistakes I’ve made. Perhaps it would be too long!

@ Rosario – yes, that’s right – at point of retirement. On the run-in to retirement I split my assets into two.

1. My main portfolio – entirely in SIPPs. I still can’t access that for almost another year.

2. Bridging funds – entirely in cash. Ultimately calculated as 6 years of income plus 3% inflation per year. My inflation guess proved way short of the mark as things turned out – this was pre-Covid. (I had some index-linked saving certs too. Thought of those as emergency fund.)

My strategy relied heavily on pension tax relief – hence retirement funds in SIPPs. I always had some cash though and then switched hard to cash saving in the last 18 months or so before retirement i.e. I gave up on tax relief. There was probably a more optimal way to do it.

The bridging fund was never invested. I didn’t, say, start investing in an ISA ten years beforehand and then switch to short bonds or cash, say, with five years to go.

You’ve got me thinking now – maybe that would have been a good idea. Certainly it would have been in retrospect. The way forward was much fuzzier at the time. The final leg came together faster than I expected – a fortunate combination of good returns and a high saving rate.

re: risk-on. IIRC I was about 80/20 until 2018. Then 60/40 after a correction helped me realise I had a lot at stake. I don’t think I’ll ever hold less than 55% equities unless I annuitise.

What’s your plan?

@StuartB – I largely agree. That’s why I added the boxout explaining that the non-equity portion goes into defensive holdings – which includes cash. I can’t edit quotes where other people mention “bonds”. That in itself is shorthand for: “short/intermediate high-quality government bonds”.

I think you’re right that the role of bonds was generally oversimplified. Bonds are such a wide category that include assets every bit as volatile as equities and some almost as tame as cash. We wrote lots of articles before 2022 trying to point out that not all bonds are alike. I don’t know how much difference it made.

Bond articles aren’t typically widely read. I don’t know if that’s because bonds feel unfamiliar and counterintuitive? Or people just find them boring?

I’d just add, it’s interesting to read Paul’s comment that bonds were overvalued in 2012. He proved 10 years too early. In the meantime intermediate-to-long gov bonds hammered cash.

There should probably be another rule-of-thumb that helps investors allocate away from intermediate govies and into short as they get closer to their target.

Anyway, I do take your point although Monevator doesn’t advocate for just holding bonds on the defensive side. I’m not sure any other site out there is banging the drum for defensive diversification as much as we are.

Just saw that I have the same user name as another post. Have amended mine to Hal17. 🙂

Thanks @TA for a timely and super-helpful update. It’s also incredibly useful and reassuring to be allowed a glimpse of the personal strategy and philosophy of someone who’s forgotten more of this than I’ll ever know!

@TA

Thanks, plenty of food for thought there. I see a lot of similarities between your position (at a point in time) and my own.

I’m mid 40’s possibly around 3-4 years from FI but due to skew towards pension I’m not likely to have the ISA bridge for another 2-3 years beyond that.

I’m maxing ISA contributions but still continuing to contribute heavily into pensions on account of tax and childcare circumstance. 2 years to go until that situation changes.

I’ve been almost entirely equities until recently. I still am in pensions but ISA is now 60/40 with the 40% following the all weather allocations. My plan was to contribute solely into the defensive parts until a couple of years from RE but lately I’ve been starting to feel I need to be lower risk in ISA’s.

I wonder, did Paul ever get round to finishing his book?

Can’t help feeling it’s easy to slip into seeing retirement/FI as the finish line for the ‘how long is my investment horizon’, when of course it’s only a border to cross. We may need some of the funds then, some we may not need for as much as another 40 years!

Thanks for updating this excellent overview!