This is part two of a series about the safe withdrawal rate (SWR) for a portfolio in drawdown, and how to improve it.

Unfortunately I set the cause back a bit in the first part, when I showed that the UK safe withdrawal rate is quite dismal – just 3.1% for 30-year spans, versus the commonly cited and far cheerier 4% rule that’s derived from US data.

On the other hand, it’s possible to argue that all safe withdrawal rate strategies are excessively doom laden.

SWRs are founded on the historical worst-case. Normally things turn out brighter than that. Moreover 155 years of data for the 60/40 portfolio shows that the UK SWR was 4% or more some 88% of the time.

So mostly you didn’t fail if you followed the man with the moustache.

Anachronistic heuristics

The problem is your SWR is only knowable in retrospect.

Well, your heirs can know it. You’ll be past caring.

But for my part I’d like to find out if there’s a way to track retirement portfolio wellbeing in real-time.

Can we get advance notice if it’s on the path to the sunlit SWR uplands? Or if it’s plunging into the valley of death, despair, and cat food?

Just how soon can we tell whether withdrawing 4% – or whatever number – is draining our portfolio like it’s Dracula’s supper, versus doing no more damage than a flea who fancies a light snack?

Spot the dog

The way I’m going to tackle this initially is by asking what bad looks like.

Do the historical worst-cases have specific features in common? If so, this could point the way to spending more freely when your retirement dashboard isn’t ablaze with warning lights.

By the same token, if we can pinpoint the difference between a downward spiral versus everyday turbulence that doesn’t stall the engine, then we won’t have to spend all our time clutching worry-beads and praying to the investing gods.

It’d also be nice to avoid the trappings of dynamic withdrawal rates and other complications designed to preserve portfolios, if only because many people seem reluctant to use them.

Perhaps we can instead find simpler rules-of-thumb that operate on more of a pay-as-you-go basis.

Investing returns sidebar – All returns are real annualised total returns. In other words, they show the average annual return (accounting for gains and losses), are inflation-adjusted, and include the impact of dividends and interest.

The SWR haves and have nots

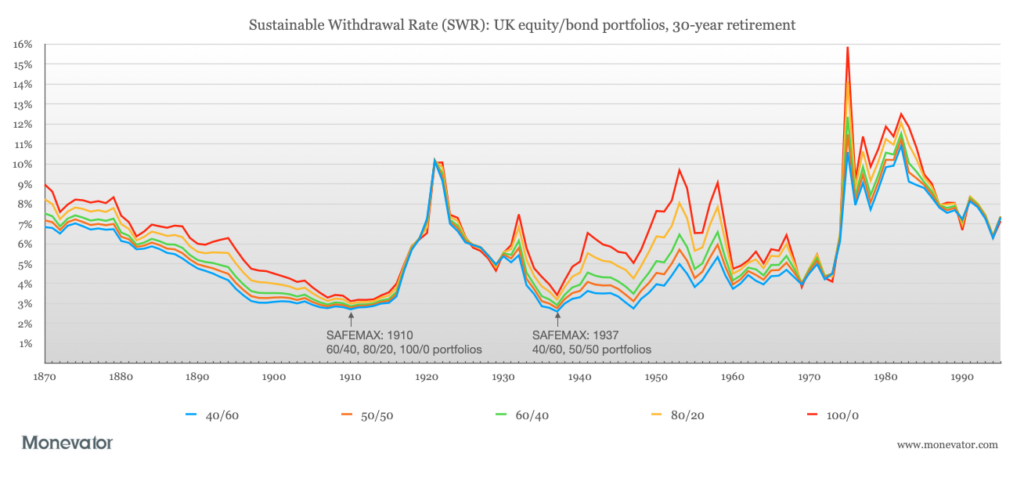

The chart below divides the UK’s notional SWR retirees into two camps: those that benefitted from a 4% withdrawal rate and higher, and those that, as I believe Keynes put it, “Had a ‘mare.”

Author’s own calculations. Data from JST Macrohistory 1, FTSE Russell, A Millennium of Macroeconomic Data for the UK and ONS. March 2025

Team Unlucky’s SWRs fell below the 4% line. These include every retirement cohort from 1896 to 1916, bedevilled as they were by World War One and its economic aftershocks.

Then there’s the 1934 to 1940 crowd. I’m not sure what they had to complain about? World War Two wasn’t ideal, I s’pose.

But there’s more to it than that, as shown by the 1946 to ‘47 group who were sucked under too. Indeed, the UK’s most flaccid SWRs can’t simply be written off with pat reference to a couple of world wars.

1917 retirees, for example, enjoyed a bouncy 4.8% SWR – despite their golden years stretching through two global conflagrations, a pandemic, and a Great Depression.

Most surprisingly, the class of 1932 lived high on the 6.2% hog, despite the onrush of the Second World War.

Near misses

Two later cohorts skated close to disaster but didn’t quite fall through the ice.

The 1969-ers were on track for the worst result ever until they were bailed out by the wonder years of the 1980s. (1969 was also the low point for US portfolios priced in GBP, as we saw in the last article.)

1960 retirees also nearly came a cropper. They ran a similar gauntlet of stagflation, plus huge crashes in the UK stock and bond markets.

Aside from that, most of the other cohorts sit comfortably above 4% – albeit the Y2K-ers are having a nail-biter thanks to retiring on the eve of the Dotcom Crash, swiftly followed by the Global Financial Crisis, post-Covid inflation, and Lord knows what’s to come with Agent Orange at the controls.

So with that lot swept into the bucket of the SWR damned, what can they tell us about the different roads to perdition?

A bad start

Famously, sequence of returns risk is a major hazard for retirees. That is, a string of bad returns early in retirement is far more consequential than if you took the same hit in later years, with your clogs fit to pop.

Researcher Michael Kitces established that the first decade of equity real returns had the biggest impact on US safe withdrawal rates for 30-year retirements.

Kitces found that a couple of down years at the beginning of retirement actually had a fairly low correlation with SWRs – down in the vicinity of 0.28.

The average 10-year real return for equities was much more predictive: producing a 0.8 correlation with the 60/40 portfolio’s safe withdrawal rate.

The correlation then dropped to 0.45 for 30-year annualised real returns. That’s because the final years of retirement exert less influence on the overall outcome.

The upshot is you don’t have to sweat a few years of bad returns when you’re fresh out of the gate – especially if markets bounce back quite quickly, as they did after the GFC.

Across-the-pond life

However, what’s true for the US often doesn’t hold for the UK. So I performed the same test on Blighty’s data set and discovered that our danger zone is the first 15 years.

The table below shows us the correlation between real annualised returns over various time periods and 30-year UK safe withdrawal rates for 60/40 portfolios:

| Equities | –Bonds– | 60/40 portfolio | |

| 1 year | 0.38 | 0.4 | 0.43 |

| 5 years | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.7 |

| 10 years | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.85 |

| 15 years | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.92 |

| 20 years | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.88 |

| 30 years | 0.63 | 0.7 | 0.73 |

The UK’s track record tallies with Kitces finding that the first few years don’t tell us much about the path we’re on.

However we’ll probably have a very good idea after 15 years. A 0.92 correlation indicates that our portfolio returns during the first half of a 30-year retirement are likely to have a decisive impact upon the overall amount of spending the portfolio can support.

The first decade is highly informative, too.

And while the correlation of SWRs with the UK’s 30-year annualised return is much less by comparison, it remains high enough that the hindmost years clearly count for something.

Later on we’ll see that extreme events in the latter half of certain retirements can still deflect their course, for better or worse.

To sum up the above: A couple of bad years at the beginning of a retirement aren’t worth fretting about (unless they’re apocalyptic). However, ten to 15 years of poor returns are likely to lock you into the low SWR dungeon. If that happens then your portfolio probably won’t last unless you rein in spending.

What do we mean by poor 15-year returns?

Exactly what kind of lacklustre 15-year return is associated with which bleak SWR?

This scatter plot graph enables us to pick out the patterns:

The WOAT 2 SWRs (red lozenge, ranging from 2.85 to 3%) are associated with 15-year annualised returns of 0% to -6%. So if you average more than 0% per year (inflation-adjusted) in the first half of your retirement, then you’re probably not going to scrape the depths in the endgame.

Next, let’s look at the same chart again, but refocus our red lozenge to take in almost the entire negative return cluster:

This view suggests that if your initial 15-year returns are negative then you can pretty much rule out a 4% SWR. Indeed, you could be heading into horrible history territory.

There is one exception. The green arrow points to the 4.15% SWR achieved by the class of 1960. They got that despite chalking up grim -3.2% 15-year real returns.

Stick around and I’ll show you under the bonnet of that journey in the next post in the series. (Consider that a warning!)

Suffice to say, I wouldn’t bank on that miracle happening again if I was clocking -3% 15-year returns.

Alright, let’s take a final goosey at the scatter plot. This time the red lozenge of fate falls upon what you could have won with weak positive returns.

Scraping a 1-2% real return puts you in a wide band where the SWR outcome is likely to lie somewhere between 3% and north of 5%.

Lastly, bagging the 4% long-term average return for a 60/40 portfolio (green lozenge of destiny) is associated with a 4.5 to 5.5% SWR.

Incidentally, the 15-year annualised return for Year 2000 60/40 retirees was 3.2%. The trendline suggests that – if they’d been doing this analysis in 2015 – they could have hoped for a 5% SWR while fearing the worst downside result of just over 4%. By my reckoning, this cohort is on course for a 4.5% SWR, assuming they average a 0% return over their remaining five years to 2030.

The story so far…

Our scatter plot provides some guidance as to the historical dispersion of outcomes.

Although it must come with the usual tug of the forelock to uncertainty.

History does not span all there is to know. For example, all bets are off if World War Three rips humanity a new one tomorrow.

SWR Cluedo

Let’s now chug on our thinking pipe and line up our main suspects in the mysterious case of the battered SWR.

Whodunnit? Was it inflation? In the grocery store? With the shocking price of bacon?

Here’s the movements of 15-year average inflation and SWRs during the periods in question:

We have our culprit, officer!

Clearly the worst SWRs go hand-in-hand with high average inflation (orange line). While falling inflation corresponds to the SWR heights.

Not so fast! It’s curious that peak inflation is not associated with the most calamitous SWRs. And some cohorts scored amazing SWRs while inflation was doing its worst. For example, 1977 delivered a 9.8% SWR despite tussling with 7.5% average inflation for the first 15-years of its cycle.

High inflation is a trouble-maker then, but it doesn’t act alone.

Let’s layer on 15-year annualised real returns in blue:

This chart gives us a better picture. Especially when you train your eyes on the blue plunges below the grey 0% returns line.

The slump associated with World War One 3 is by far the deepest.

World War Two is relatively mild by comparison. Hence only seven cohorts slipped below the 4% SWR line (1934-1940) whereas fully 21 did under the malign influence of the First World War (cohorts 1896-1916).

Still, we can also see that the 1946 to 1947 brigade fell below par despite positive returns. Whereas 1960 kept its nose above water while coping with a sharp below-zero dive.

A tale of two retirements

Those latter results help show that the second half of the portfolio’s lifespan does matter.

Both the late Forties crew and the Sixties swingers were in trouble by the end of the first 15 years – with the 1960-types looking slightly more precarious. But then the 1960 cohort enjoyed a double-digit romp to the finish line. Essentially, they were bailed out by 13% miracle-gro returns for the last 15 years. (Still, even then they only managed a 4.2% SWR.)

In contrast the fate of the Forties mob was sealed by mediocre returns in the 1960s (2.6% annualised). The crash of 1973-74 finished them off but they were already on life support.

What do I take from that? That the 1960 journey is the exception that proves the rule. They needed a Hail Mary to sustain a passable SWR and they got it.

But if your portfolio was looking similarly anaemic after 15 years, it’d be more rational to assume the 1946-47 outcome and cut back your spending accordingly. (Or to think about annuitising the bulk of your portfolio, or to take out a reverse mortgage, depending on your options.)

Looking for a sign

Behind-the-scenes of this post, I’ve spent some time delving into the individual paths taken by the UK’s many retirement runs.

I’ve found it tremendously helpful to look beyond the standard worst-case SWR scenario in search of common signs of distress that anyone could monitor to avoid spending down their portfolio too quickly.

And I think I’ve found some useful pointers! I’ll share those in the next post.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

Bonus material: Why use the UK’s safe withdrawal rate history?

It’s important to recognise that neither the UK, nor the US, nor the World is locked onto any particular safe withdrawal rate path.

As I alluded to earlier, if we nuke ourselves to Kingdom Come then the global SWR goes to zero.

That’s that. Do not pass the Great Filter. Do not collect $40,000.

But let’s be positive. Let’s assume we don’t face a future being bent into paper clips by our AI overlords. Then we’re left with a range of possibilities which the past can help us scope.

The problem with the US safe withdrawal rate is that it looks fortuitous. It’s based on a timeline in which America won the 20th Century.

The World portfolio fails to match the US SWR, as does every other country except Denmark. (See Wade Pfau’s paper: Does International Diversification Improve Safe Withdrawal Rates?)

Huh? Tiny Denmark? Conquered by Nazi Germany Denmark? Yep, and South Africa was Top Five, beating out many more powerful and economically successful countries.

Explain that.

More significantly, Pfau found that no country – not even the US – could replicate William Bengen’s original 4% SWR finding.

Why? Because Bengen, the author of the 4% rule, relied upon a dataset containing better US historical returns than the one used by Pfau. Both archives are well credentialed. Both offer a version of the past. But the differences between the numbers reveal there’s nothing inevitable about the 4% rule – even if you invest solely in the US.

Should US assets exhibit a moderately worse sequence of returns in the years ahead than they did in the past, then future American investors may have to anchor on a 3% rule – or something nastier still.

That’s a plausible outcome. Hence retirement researchers have turned to international datasets and Monte Carlo studies to challenge the assumptions embedded in the US’s exceptional past returns. (I’ve previously used one such database to determine a World SWR of 3.5%.)

What’s interesting about the UK’s SWR history 4 is that it enables us to envisage a future which is a little worse than the American past. One of geopolitical decline. One where they confront military catastrophe but avoid utter disaster. One in which inflation is stickier than the US has previously experienced.

It’s not hard to imagine.

The UK safe withdrawal rate is an antidote to excessive optimism. It helps us avoid clinging to the singular path taken by the US, as if inferior outcomes are not possible.

Aiming for a 3% SWR, say, gives you greater downside protection – or it can be the prompt for serious research into how to improve your withdrawal rate from that baseline.

- Òscar Jordà, Katharina Knoll, Dmitry Kuvshinov, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor. 2019. The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870–2015. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(3), 1225-1298.[↩]

- Worst Of All-Time![↩]

- The blue line shows you the average returns for the 15-years beyond each data point on the chart.[↩]

- The UK was ranked 8th out of 20 countries in Pfau’s paper.[↩]

I started out with a 3.25% SWR six years ago when I retired (6 months before pandemic hit) – I also put a couple of years worth of drawdown in cash savings.

The other thing to factor in is any pensions you may receive – state or otherwise (defined benefit) – as time has moved on and I have taken these I get a solid predictable buffer of monthly income – so that the SWR drawdown funds are the (less predictable) later on top.

The amount of pension income you can take may also influence the asset allocation you decide on for the pot you are drawing down from – due to the income stability a monthly pension provides

I started with some trepidation but so far it has worked out fine and I have stuck with the original 3.25% figure I calculated – making occasional uplifts for inflation.

The obvious insurance against longevity risk is buying index-linked annuities.

But many people entertain an intense hatred of annuities. It’s so common that economists and actuaries have a name for this strange reluctance to behave rationally – The Annuity Puzzle.

Just as we all dismiss the insanities of the young, with their daft quasi-religious obsessions, perhaps we should mock the delusional anti-annuity zealots among the ageing.

@TA:

Nice post and keeping it UK grounded is IMO completely sensible.

Are you familiar with ERN’s part 38? I ask as it has a lot of related info. One thing that particularly struck me wrt your post (although it might not apply in the UK) is ERN’s assertion that: “the sequence matters roughly twice as much as the average return” which strikes me as a useful “rule-of-thumb”; although I not sure how you can practically apply it!

Honestly, why torture yourself with SWR of 3.5-4%, when you can lock into Joint Life annuity rates of

– Level = 6-6.5%

– Inflation protected = 4.5-5%

This is looking to be an interesting series. A couple of comments.

1) Falling inflation and good SWR. This may at least partially be a result of good bond returns in such cases since yields tend to increase when inflation is high and then yields fall once inflation starts to drop (leading to increases in prices of the high coupon bonds and consequently to strong nominal and real returns).

2) While it uses US data, the article at https://portfoliocharts.com/2024/03/15/how-to-harness-the-flowing-nature-of-withdrawal-rate-math/ is an interesting analysis of SWR and projections thereof. While I will leave the details for those interested in reading further, one interesting point (obvious in retrospect, but it never struck me prior to reading the article) is that for a given start date, the SWR for the 30 year retirement must be less than the SWR to date (e.g., taking your 15 year review, the SWR after 15 years must be greater than the SWR after 30. At least this gives an upper value for projections.

Thanks. A couple of points:

For a 60:40 portfolio, what bond duration is modelled ?

Also, I am doubtful of the common analysis which has a start year and then considers the next 30 years, then increments by one etc.

Two consecutive data sets only differ by one year out of the 30 so are far from independent, and within that consecutive years must also show some degree of correlation. Plus there are secular changes/paradigm shifts.

I think you can over analyse this sort of stuff.

@Jelly — Agree that annuities obviously look much more attractive than they have for many years. But that doesn’t make investigating what drives SWR success and failure – or what realistic numbers might be – irrelevant, IMHO.

To quote the numbers you do as attractively, you’re implicitly comparing them to what you could get elsewhere. A portfolio in drawdown following SWR principles might be one option. A linker ladder might be another. A lot of people might (not especially sensibly!) just compare it to cash in the bank. Exploring the territory helps set these parameters, which are always shifting too.

With that said we could do with covering annuities a bit more, I’d agree about that. Pending an expert! Though even @TA has said he might annuitise a bit so I guess he’ll get around to them eventually 😉

Another cracking article – thank you.

In particular, I like the way that you have carried out the analyses in a useful and illuminating way. Again thank you, because I know from experience how much work (and time this takes). But it gives us a better understanding of the key risks (inflation and investment return). And they seem to work in tandem to lower the SWR, which is another interesting feature.

To be honest, the sequence of returns aspect was probably the prime reason I chose to annuitise recently. It seemed to me that the outlook for the next few years wasn’t good. A bit ironic having steadfastly followed a (very) passive buy and hold policy for the vast majority of my previous investment life.

Something like https://www.bogleheads.org/wiki/Variable_percentage_withdrawal appeals to me more than the notion of a SWR. VPW is inherently robust to sequence of returns, and its assumptions (especially expected return) can be easily revised at any point in time throughout retirement.

I also don’t understand how FIRE community can get anchored to a _single_ SWR figure, be it 4% or 3%: surely the figure should depend how _early_ one retires.

I half remember seeing a chart of SWR on the y and retirement duration on the x. Was that here? It was quite useful and I believe the takeaway was it doesn’t drop very quickly, i.e. 40 year retirement not much lower than 30. But memory is hazy…

@LateGenXer: +1 for VPW.

The idea of set once, adjust for inflation and forget for 30 years is unrealistic. The beauty of VPW is that you can adjust monthly. Every withdrawal is dependent on cautious guess of future returns and your balance at withdrawal. But it does need to be used with a stable floor income and in the UK nearly everyone will receive some form of state pension and/or pension credit.

Super piece. Thanks @TA. 🙂

Any thoughts if this affects your view of endless SWR v VWR/VPW v Natural yield v Annuities debate?

I’ve read of some CAPE based approaches to VWR, i.e.: (100/CAPE x equity %) + (real bond yield x bond %).

There’s also the idea of reducing equities in the first 15 years of retirement and then increasing to account for shorter remaining life span which means SoR risk just not as important (unfortunately for all the wrong reasons 🙁 )

The thing that queers the pitch here is dependents. Parents want to leave money to their children, because they can see the world of work is tougher than they had it. Or at least they remember having it, the golden glow of the setting sun softens many of the edges 😉

Most of the calculation are atomic, one individual, how well do they do. There’s also a presumption of constant spending – I CBA to chop my own wood any more, I pay people to do that. I eat better and probably waste more money. But let’s leave the spending aside. In theory you don’t have to become more decadent as you get older.

The annuity paradox isn’t such a paradox when it comes to parents featherbedding their adult kids – all of a sudden taking your chances in the market is more attractive than an annuity, because the latter dies with you.

Even for the un-childed an age gap between partners can extend the time horizon.

That 30 year target is for normal people who retire after a 35 to 40 year working life, it usually takes you to ninety-something. I know all you high flyers who have taken over the FI(RE) space are so wedded to the joys of working that you may be FI but don’t RE, and are happy with that. Obviously if you don’t stop working, even if you change down a bit that so dominates the SWR as to render it moot. But it’s not so long ago that the personal finance space was also occupied by people dreaming of retiring in their early forties. A SWR based on 30 years ain’t gonna cut it, you’ll be running in extra time after your three-score years and ten are up.

I’m not taking issue with the SWR computation, but people’s family settings are not always as atomic as that, and it is rather predicated on a normal retirement at sixty-ish. My working life was shortened by more than 20% by retiring early, and I didn’t retire in my 40s. If I live 30 years after I retired I would die younger than either of my parents who weren’t in the greatest of health. Treat that 30 year assumption with care.

The space on Monevator has changed since the FI/RE space of the post GFC generation – much more high flying, and much less likely to actually stop working on reaching FI. You’ll be absolutely fine because you will continue accumulating past the notional FI date. I’d say it is the chance of doing the RE thing that has become much harder now than it used to be.

@tranq – I’m glad it’s working out for you so far, especially as the markets have had quite a bumpy ride! Quite a few people who’ve commented over the years have spoken to the acclimatisation period you mention. That is, they were very cautious at the start then grew in confidence over time. Decumulation does seem like a skill or lifestyle that takes getting used to.

@Al Cam – I have read that post back in the day but don’t remember much of it now. Will reread – as far as I’m concerned ERN is the gold standard.

The part you quote is really interesting too. I guess it implies that a decumulator should start with an abundance of caution. While I think that’s true, I’m inclined to down weight that mathematical conclusion in light of my experience of people in my parent’s generation not going the 30-year distance. Plus the stark reality of the go-go years turning into the no-go years. I’m not saying I’d kick off with a 5% withdrawal rate, but I’m personally thinking more and more about enjoying life / spending a bit more while I can.

@Jelly – I know what you mean and partial annuitisation is on my radar. A couple of notes of caution: no-one was quoting annuity rates a few years ago – except to say they were awful. We could go back there. Also, I was listening to the Rational Reminder podcast the other day and the PWL guys were saying they couldn’t get their clients interested in annuities despite the revived rates. The annuity puzzle is alive and well as @dearieme says.

@Alan S – completely agree about the role of bond yields as inflation falls away. Particularly noticeable in the late 70s and after 1921 especially as deflation sets in. Thank you for linking to that Portfolio Charts post. Will give that a read.

@Mr Optimistic – Bond portfolio:

1870-1901 perpetuals

1902-1989 20yr gilts

1990-2015 15yr gilts

2016-2020 10yr gilts

2021-2024 FTSE Actuaries UK Conventional Gilts All Stocks

If you’re interested, can I recommend a paper by a certain Alan Stocker. It’s quite eye opening:

The Effect of the Maturity of Gilts on ‘Safe’ Withdrawal Rates in Retirement

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4742456

@Nick H – Cheers! I think annuitisation is a great option. I need to take another look at the rates. Because I anchored on not having to think about it until age 70 or thereabouts, I’m finding it difficult to confront now that rates have dramatically improved all the way down the age curve. I am the annuity puzzle incarnate.

@LateGenXer – I’m very interested in VPW. ERN put it through its paces if IIRC. I’d need to reread but my memory is he liked it but found it could lead to significant drops in income during tough retirement cycles. Of course, the same is true of all dynamic withdrawal rate strategies, so I don’t mean to single VPW out from that perspective. I can’t remember if ERN found it was better or worse than others in his test. Have you unleashed your modelling skills on it? I’d like to see how it fares with non-US data.

@Rhino – I don’t remember that chart but it sounds good. Last episode I found a reasonable difference between 30-year and 40-year portfolios: 2.9% to 2.4% for the UK 60/40. It kept going down too. 50-year was 2.1. https://monevator.com/safe-withdrawal-rate-uk/

@ermine #13: maybe Rachel Reeves has done us all a favour in disguise by making pensions much less suitable as an IHT mitigation vehicle? Knowing that we have to spend the SIPP or have our estate face IHT on death forces a confrontation with what a suitable SWR (or VWR ‘formula’) should be in order to ‘die with zero’.

I’m one of the ‘atomics’ here (the male equivalent, I suppose, of JD Vance’s “childless cat ladies”), and fully intend, in the ideal world, to have enough to last until death but to die with an insolvent estate, with the only debts being to businesses that have hacked me off during life 😉

It’s tempting to just use 3% as a fixed SWR but so much can and does happen over 30-40 years (given so many of us will see our nineties) that a variable approach or natural yield (or 1 day a week PT top up to retirement back in the office) seems a less fraught ‘solution’ of sorts to the first 15 years’ or so of acute SoR risk in retirement, as highlighted so adeptly by @TA above.

We never know if now (or say 2035, depending on when one is planning on retiring from, at least, FT work) is going to be an 1896-1916 or a 1977-1995 scenario.

Looking at the SWR rate over time in green on the charts above makes me realise why the surviving cohort who made it out of the world of work 30/35 years ago seem now, in their 90s, so contented. They got the better bargain from fate.

But being a half empty glass type, I’d not like to wager that – in the temporal spectrum of ill to good fortune – I’ll find myself on the better end of that scale by 2030 or 2035, when it comes to my own SWR.

@DH – Cheers! I’m going down this path for a couple of posts because I think so very few people want to layer on extra complexity in the form of another explicit set of rules. I think – instead – many people intuitively apply their own variable withdrawal rate using instinct. For example, spending a bit less when they see their investments contract.

But the downside is regular comments along the lines of: “Markets are down, FIRE just got a lot harder!” I’ve even caught some of that myself – emotionally if not rationally.

So I’m spending this post and next post looking at what a bad start does tell us about our chances of scraping the bottom of the SWR barrel.

Later on I hope to model some variable strategies including VPW if my spreadsheet skills are up to it. I do intend to use this type of strategy myself because the real danger with SWR is the amount of wealth you’re liable to leave unspent when things go tolerably well.

Everything I’ve read on natural yield points to it being a mental accounting exercise. I’m a big fan of index-linked annuities. I do think they’re part of the solution, especially for Gen X defined contribution types like me.

Very interesting and clearly a huge amount of work to generate these articles.

I was grateful to survive very poor returns from my first two years of Fire (2007-2009) but the data clearly suggests this wasn’t likely to be a huge problem ( my self congratulations were clearly misplaced !)

I’m 18 years in and clearly not doing as well as I was in February but very roughly I’ve doubled the portfolio in real terms after an approximate 3% spending each year, over 18 years, which has grown at the same real rate of return of the portfolio ie inflation plus about 4%…

So we’ve passed the 15 year point and if I live as long as my parents we need another 30 odd years of income.

This is a reasonable result, but we have had a following wind for the last 15 years or so…

At the beginning of retirement I did not think that spending would grow at such a rate and no doubt I could bring it down sharply but it’s nice not to have to care…

So a period of good years could sow the seeds of unpleasantness if reducing spending was required…

The rational argument of course is that if you are fortunate to be on the right side of the SWR issue , do you live it up ? ( Or do you save it and risk being the great benefactor/richest person in the graveyard ? )

Thanks @TA for a great piece, really appreciate the work that’s gone into this. Love to see a follow up piece on annuities – as a Gen-X DC’er fully intent on RE the second I’m FE!

@DH #15 – I suspect they look so contented as they’ve got DB pensions and have done extraordinarily well from property.

@LateGenXer Thanks for the VPW link – that’s right up my street.

I had been thinking of using a fixed percentage withdrawal to keep things simple. I don’t think it’s realistic to expect inflation proofed withdrawals regardless of returns.

The other thing that strikes me is that the UK state pension with its triple lock needs to be taken into account in any of these calculations.

@DH – I forgot to ask, can you send me links to any CAPE approaches you like. If you have ’em handy?

@TA #21: I’ve made a note of this one from Mike over at 7circles (think his PF site may have gone into cold storage as no new posts since October), taken I think from his 7th circle on decumulating, under his heading ‘the Plan 2’ (most of the site’s paywalled, but I got this titbit from the free part):

“Dynamic Spending can help with SoRR.

Fixed guard rails don’t work (they lead to dramatic spending cuts).

CAPE-based spending rules [e.g. 1.5% + 0.5%*(100/CAPE)] do work”

Checking my notes, I now see that he’s using the CAPE (I’m not sure which, presumably Global Equities, so either MSCI All Countries or FTSE All World) a bit differently to my thoughts (i.e. for the equity element he’s applying a 0.5 factor, that is to say using just 50% of the inverse CAPE, or Cyclical Earnings Yield, which seems quite cautious to me – a man’s got to live off of something after all!)

I think (but do not know) that the 1.5% bit must be an assumed typical real yield for ILGS across durations (i.e. for a linker ladder).

Mike also seems keen for decumulators to begin increasing their equity allocation after the worst SoR (SoRR as he calls it) risk is in the rear view mirror, and aim to get up towards 75% at death, which is pretty punchy for most I’d guess.

@TA: I have a couple semi-related thoughts on this topic:

1) Whenever I’ve seen folks do back testing to look at SWRs and figure out probability of success or failure (or related topics), it seems each retirement starting period is equally weighted. That is, they look at (for example) 100 years in which a prospective retiree might have begun retirement, and if (say) 5 fail, they award a 95% success rate. However, intuitively, it would seem to me that it is more likely that aspiring retirees would hit their “number” in years or periods of strong market returns (i.e., when asset valuations are relatively higher), and that relatively fewer (perhaps even none in more severe cases) would do so in periods of material drawdowns (i.e., when valuations are relatively lower). I haven’t run simulations of this myself, so I don’t know for sure, but it would seem that this might significantly skew the results. It would be really interesting to run an analysis where the starting period is the year the prospective retiree begins accumulating, and the retiring year is the beginning of the year after they first hit their number.

Running a simulation with a large number of people starting in each year, each with a their own savings rate and real income growth rate, and then seeing how the retirement years clump together and how that then affects success rate would be very interesting.

I think this relates to your article today as it might give some earlier indication as to whether you should aim for a more conservative starting withdrawal rate (e.g., does it look like you’re in a year where very many people hit their number, or not?).

2) The idea that you can be 15 years into retirement and see warning signs, but *not* be able to see them at retirement time itself is interesting to me. The reason for this is relatively simple: One way of assessing whether you’re still “good” would be to look at each new year as a “fresh” retirement. If you did that, the moment your assets fell in value sufficiently such that your SWR would be above your “happy” threshold, you’d take some action, because you’re clearly not “done accumulating” yet. Either trim expenses so that your SWR was healthy, or go back to work, etc. But folks tend to *not* look at each year as the start of a new retirement, and this post as an example is looking at ways to figure out future likelihood of success 15 years in. The only way that this makes sense to me is if one believes that past years’ performance has some capacity to predict future performance (which at a macro level seems not unreasonable to me). But if this is the case, and there is a way to determine likelihood of success 15 years in, couldn’t you take the same approach at initial retirement time to better figure out your chances of success at any given withdrawal rate? After all, a very long retirement shortened by 15 years is still a very long retirement. This relates to the first point, as it might point to basing your SWR on more than just the current valuation of your assets, taking into account how valuations have changed over the past several years. Doing this could both move your SWR up and down, depending on the situation. I know some have proposed CAPE-based withdrawal rates, which is one example of this.

Anyway, I hope this all makes sense, and apologize for the essay :-).

@TA:

Would it be about right to say that the returns HS mentions at #17 would equate to around 7% (ie inflation plus 4%* plus 3%) on your portfolio returns graphs above. That is, can please confirm your graphs are purely [real] Pot returns ie without any SWR drawdowns?

*4% PA comes from rule of 72 for doubling across 18 years

@TA, thanks for the reference I’ll check on it.

On annuities, I have been rethinking how to structure investments for my future widow :).

Yes an annuity should be part of the mix but the kicker is that all our investments are in ISA’s so you are giving up the tax free ISA for a taxable annuity. I think this alters the logic.

The other more immediate issue is rebalancing of haven assets. Having bought gold to shelter against dysfunction times the holding has gone up to 15% of the portfolio. Having bought it to shelter against hard times, those times have now appeared and the investment has and is doing it’s job. In these circumstances it is very hard to take profits through rebalancing !

Should ‘haven’ assets be exempt from rebalancing ?

Purchased Life Annuities (PLAs) bought with non-pensionable assets are only subject to income tax on the interest element and not the whole of the annuity payment

Whereas, Pension Annuities are liable to income tax on the whole of the annuity payment

https://www.mandg.com/wealth/adviser-services/tech-matters/investments-and-taxation/purchased-life-annuities/purchased-life-annuities

Worth reading a Monevator guest post by Mark Meldon on annuities

https://monevator.com/annuities-guaranteed-income-for-life/

@DH – thank you! I’ll have a root around at 7circles.

@Hariseldon – I was struck by your description of what could be 45-years in decumulation. That really is extraordinary. With genetics like that, taking a side-bet with an annuity provider may not be a bad idea. That said, doubling your portfolio’s real value is an awesome result. Effectively, you’re now looking at a 3% SWR for a fresh 30-year retirement.

@Chris – all great points. I haven’t seen any research systematically analysing the accumulation side of the equation but I have read discussion of it. As you say, it’s highly likely that the majority of people pull the plug when the market and thus valuations are high. This suggests we should temper our SWR expectations if we retire at such a time (I did!) and that a CAPE-based SWR modifier could help. ERN uses this approach.

I have not found UK CAPE data pre-dating 1979, which doesn’t give us much of a track record to play with (latest full 30-yr retirement begins 1995). Still, I think global CAPE is likely to have some value, this paper is a good read on that point: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2558474

I have used Global CAPE to modify my own SWR.

Re: your second point. I’m heading in precisely this direction! Each year can be viewed as the start of a fresh retirement modified by your life expectancy. You’re right that it would make sense to overlay a valuation measure like CAPE over such periodic reviews too. CAPE’s predictive power diminishes under 10-years but I’m doubtful I’d still want to plough this furrow if I thought I was likely to check out within 10 years. I think I’d more likely annuitise for sure by then.

@Al Cam – Yes, real time-weighted UK 60/40 total returns, no withdrawals.

@Mr Optimistic – heh, great point about how hard it is to rebalance in times like these. Have you breached your rebalancing threshold? Then you know what to do! 😉

@TA (#28) & @HS(#17)

Thanks.

Re: “Effectively, you’re now looking at a 3% SWR for a fresh 30-year retirement.” I get the idea, but I think this is only the case if @HS’s annual spending increases slow down to be inflation rather than around inflation plus c. 4%.

Yes, excellent point 🙂

@Delta Hedge — You write:

Yep, it looks like another one bites the dust 🙁

Monevator is now basically the only independent non-corporate general investing site operating with any scale in the UK I think. (I don’t count the likes of Boring Money which raised £3m a few years ago at a £25m valuation!)

The free site continues to be mullered by Google. The latest algo update has again cut our (already much cut) free site traffic by another 20% or so.

Good work Google! I’m sure UK investors will be better served by the big banks and so forth you’re sending them to…

For those who’d like to support us on a use-it-or-lose it perspective:

https://monevator.com/membership/

Maybe I should be pushing this more aggressively while there’s still time, IDK.

Thanks as ever to those of you who have signed up as members! Mavens is only £3 a month.

(A quick skim of the Moguls/Mavens badges in these comments shows it’s still a minority, even among the regulars who have been commenting for a decade and so presumably value this website and its community but still can’t find £3 a month – or even cheaper £30 a year – ho hum… 🙁 )

@ HS (#17, etc):

IIRC from previous posts/chatter a lot of your spending [ie that above a fairly steady (real) base-level of spend] goes on travelling. OOI, do you foresee your total spending continuing to increase at around the same level above inflation?

The reason I ask is other than this possible spending risk IMO you look very well set to at least age 95 barring unforeseen events. Section 4 of ERN’s part 47 on spending creep might be of some interest, see: https://earlyretirementnow.com/2021/08/18/when-to-worry-when-to-wing-it-swr-series-part-47/

Lastly, are you now in receipt of your state pension? If so, has that changed how you view things or is it too early to say?

@TI — I just upgraded to Moguls to support the site, even though I have only an academic interest in active investing.

@TA: Thanks for the response. I’ll be looking forward to what further findings you have on the topic. One day, if I ever actually pull the trigger and stop working and have some “spare” time, I may play around with some simulations myself. However, I fear the future will remain difficult to predict!

One article I’ve been longing for is how to optimise NICs, i.e. get qualifying years for state pension with minimal contribution. As a part of a glide path towards full retirement.

As Ermine is now on the pay roll, he would be perfect to write it as he’s already alluded to the various wheezes over at his place. He had one particularly efficient approach using type 3 NICs or something. The fact I can’t remember the details is why the article would be so valuable.

Hopefully you can tickle his snout to get him to write it?

@Wodger — Thank you, much appreciated indeed! Hope you enjoy the active articles as a spectator rather than a gladiator (/sacrificial animal haha)

Surely the unsaid other thing about all this is how much in absolute terms the funds start at? If you have a £350k home paid up and a £500k fund, then ~£15k a year of income plus £12k ish of state pension is OK but hardly living the life – however, you have actually £850k of assets and you could always sell your home and move somewhere cheaper, and/or rent in future.

If you had a £1m home and £5m of assets on retirement, then you could afford to take far more money up front, because you can always adjust later and still have a very comfortable existence – because your absolute baseline costs like eating, energy, council tax and so on are fixed and thus represent a far lower proportion of that income.

In short, the higher the available funds, the higher the SWR is because you’ve got your basics covered anyway and you can afford to lose income later without it materially affecting you.

On the pension floor and NIC contributions – its possible (apparently, though not well advertised) to claim a UK state pension and a second one from another country where you’ve worked for a period and built the necessary equivalent of NICs. There seems scope for being up on the deal here especially with the buy backs, if they can be applied for independently without a combinational cap.

@#37, agree, aside from net worth (level of wealth), geography, health, social status, tastes, introversion/extroversion, financial skills, curiosity and other protective factors/safety nets.

I would be disappointed in myself if I retired only to spend precious early years religiously conforming to a metric. Even @TA mentions he intends to spend more at the start to relish his youthful sparky years …

As long as dynamic withdrawal calculations accord with risk appetite, (any excessive) market fluctuations and desired end-balance, I can’t see why would anyone nominate a fixed withdrawal SWR and religiously stick to it (particularly for fifteen years out of fear).

Isn’t the whole point of gaining economic freedom, to confidently stride forth …

Thank you though, interesting article.

@Tedious: I tend to agree with you that the wealthier you are, the more withdrawal rate risk you can take, and specifically because you do have a lot more flexibility in terms of lifestyle adjustment.

I do suspect that a lot of the lean fire folk, who I often see also reach for higher withdrawal rates, are taking on more risk than is prudent. Especially when coupled with the other thought I raised above about how people will be more likely to hit their number at times of higher relative asset valuations.

@Rhino #35 NICs

If you are working self-employed and therefore declaring on SA 100 and your profits are > 6485 a year then you are sorted for NI and you have no choice in the matter. The interesting edge cases arise:

if you are retired, but declare yourself self employed and make some nominal activity. You can then fill in a SA 100, make sure you do not claim the £1k trading allowance. You do not actually have to make a profit, though I generally did, but a small amount is OK. Then pay your class II through self assessment, job done. You must be self employed for the entire tax year, NI is a whole years thing. The rates are an absolute steal, look up the HMRC link I’ve given for current rates for Class II, it’s £3.50 a week now, so about £180 p.a. The state pension 230.25 per week for the full NICs, if you are short of qualifying years then each £3.50 a week buys you about £6.57 a week more SP, you run, not walk, to that opportunity.

One of the weird groups of people HMRC cite as possibly wanting to pay class II are

but I am not clever enough to say if that means you are a retired typical monevator reader investing for yourself then this applies to you, DYOR.

If you CBA with all that self-employment malarkey you can instead choose to pay Class III NI contributions at £17.75 a week, which is still a decent annuity rate of ~30%. Index linked. Try getting that on the open market. There’s no requirement to be working or doing self assessment for class III

You first step should be to get your NI record through the government gateway, and to qualify how many years you will get through working. There’s no need to pay voluntary contributions too early in your career. Once upon a time you couldn’t make voluntary NI contributions past state pension age but it appears you can now.

Gramps looking after grandkids so their parents can work can get NICs for their caring role, I know nothing about that but worth checking out if it may apply to you, then you don’t have to pay but need to declare it somehow.

I should add to the NICs observation that

> how to optimise NICs, i.e. get qualifying years for state pension with minimal contribution.

while you are still earning, paying into your pension particularly via salary sacrifice is the big win in reducing you NICs while earning. It obviously helps reduce your tax bill too.

The kicker, is of course you have less take-home, I still remember the fellow who introduced this wizard wheeze to me with the pithy observation ‘with that opportunity you’ve got to me mad if you still working [for The Firm] by the time you’re 45’. That stung because I was 46 I think.

I had the last laugh – a few years later I got to execute that plan of his. He didn’t, he retired at 60, because it turned out his wife and kids rather liked the middle class lifestyle and the holidays in Sardinia, and pressured him to keep the good times flowing. But I didn’t pay much NICs in my salary sacrifice days, nowhere near as much as I was paying in the salad days before it all went wrong in the GFC.

@Ermine – superb, many thanks. It was the class II that I was thinking of not class III. Thanks for the memory jog. I did that salary sac into a sipp for a good few years taking myself down to minimum wage. It was a superb wheeze while it lasted but a change of employer ended it.

@TA thanks for the really thought provoking post.

The more I see SWR analysis based on historical data the more I wonder whether a prospective, Monte Carlo analysis would provide additional insights. It’s probably bleeding into DWR territory though. And you replace the objectivity of the historical data with a subjective model of future investment returns.

Such a model may be hugely sensitive to the assumptions about the distribution of investment returns for each asset class and the correlations between the asset classes.

@Prospector – I think you’re right, we’d learn something from Monte Carlo analysis but would have to grapple with a new set of drawbacks e.g. returns shorn of their real world provenance.

I think it matters that we can associate Japan’s 0.25% SWR with catastrophic defeat in WW2. Knowing that, I can effectively say to myself: there’s not much point saving up for that event. It’s not like a few ETFs in a SIPP are going to be the answer to that problem. But other countries did suffer sub-4% SWRs outside of wartime, mostly during stagflation. And I can defend against that by diversifying into inflation-hedging assets.

I probably haven’t emphasised this enough but I think it’s important to disassociate from a particular number. To that extent I agree with @London. But I want to understand where the numbers come from, so I know how seriously I need to take them. In other words, I’d like to understand the rules, so I know when I can break the rules.

Longevity risk is a great example of this. Do I need to worry about the 40-year SWR figure? Probably not if males in my family die young and I’m on forty a day. (I’m not on forty a day and males in my family seem distinctly average life expectancy-wise.)

@TP mentions that one solution is to get minted then cut back later if you have to. That’s right, though many people seem to struggle to cut back once they’re used to a certain lifestyle. And getting minted may commit you to many more years of a soul-destroying job before you feel safe enough to quit / have that decision made for you. One-More-Year syndrome is one symptom of that. (Also I’d like FI to be available to people without huge resources.)

@London’s implied rallying cry – that she’d back herself to overcome any tricky situation – that really appeals to me. I think that kind of self-confidence is a huge asset. Particularly when making a big leap like declaring FIRE, and then dealing with life as it comes at you. The way I acquire that confidence is by deepening my understanding of how to respond to easily imaginable bad scenarios.

@Chris (#23, etc) & @TA (#28, etc)

The initial comment from Chris stirred a vague recollection of some possibly relevant work. It finally came to me late last night (as I was emptying the dishwasher?!?). The paper is by Pfau and dates from 2011 (so before he became well known), see: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1876224

There is a [at least one] follow up paper. His paper called “Withdrawal Rates, Savings Rates, and Valuation-Based Asset Allocation”, also available from SSRN, may also be of some interest.

FWIW, @Chris (#23) comment 2 is an approach often used by ERN.

@Al: Thanks for sharing. The abstract looks interesting, and I’ll aim to give the paper a read. Re. ERN, I’ve seen he is an advocate for CAPE-based approaches. But he also seems to discount the value of international exposure and the risk related to bonds. However, I generally like his content.

@Prospector: I quite like simulations, but I do think that at some point there’s nothing you can really do to address the fact that the future is inherently hard to predict. At some level, making sure you’re not starting from an irresponsible place and then being willing to adapt to the future seems like a sound approach. And possibly buying an annuity when the time is right 🙂

@Chris (#47):

No worries – the thought was bugging me until last night; odd how such things sometimes resolve themselves!

Yup, ERN, like the rest of us, is somewhat opinionated.

Whilst he uses CAPE he is also keen on what you called the “look at each year as the start of a new retirement” approach – IMO, his part 38 (which I mentioned above at #3) shows this well – especially noteworthy being his pithy conclusion that “Sorry: Sequence. Risk. Will. Not. Go. Away!”.

@TA (#45):

Re: “Longevity risk is a great example of this.”

Agree; there are are many roads to hell – not just a bad sequence of returns!

Annuities solve almost all the risks of SWR

Life Insurance fixes what’s left

FREE NI Credits for childcare link:

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/apply-for-specified-adult-childcare-credits

It’s form CA9176 – my wife claimed 4 years, to fill her gap. I think the credits appeared on the NI statement on HMRC within a reasonable time frame.

And MSE link too:

https://www.moneysavingexpert.com/family/grandparents-childcare-credit/

@Jelly (#50): Annuities seem to be a useful tool, and I think can be an effective component of a drawdown strategy. However, they do pose a challenge if you want to leave dependents something when you die, and it’s not clear that they’re available for folks retiring at a younger age (e.g., 40s). Also, you do still carry the risk of the specific country in which you bought your annuity going bust (this isn’t sequence risk, but is still risk). I don’t personally know how I feel about that risk – probably that it is very low for a country like the UK – but some seem to think it is real.

@Al (#48): I think my most controversial opinion is that the only unacceptable outcome in retirement is running out of money before you run out of life, and that ending up with piles of loot at death is hardly a problem. Unfortunately it is this opinion that steers me toward seeking a very low initial withdrawal rate :-).

@Delta Hedge

7 Circles was a great site – sorry to hear it looks as though it has packed up. I got a huge amount of input from that site and Mike on how to set up my ETF SIPP asset allocation.

The ETF allocation approach and strategy I adopted were based on ideas very similar to those in Smart Portfolios by Robert Carver (a great book and fantastic resource for DIY ETF investors) which Mike covered in 7 Circles and elaborated on (he’d ben using a very similar approach himself).

The 3.25% SWR figure I adopted was based on quite a bit of research Mike had done also into this – probably in the paid area.

I took a few review sessions with Mike himself – very knowledgeable and insightful guy.

Today’s update to the Hargreaves Lansdown Best Annuity Rate page shows annuity rates at their highest level for three years (and therefore presumably at least fifteen years) exceeding even the rate spike in late 2022.

Thanks for the article TA. Greatly detailed as always.

My personal approach to this is that I use the 4% SWR as an indicative level of whether I am FI or not but I don’t attach too much to it in terms of certainty. For me I have a few contingency plans in force:

– My 4% rule is for use as a bridging gap ISA fund of 18 years to public pensions. I’d like to think it will still be going albeit much lesser value when I take my public pensions. These are for the same amount in FI yearly drawdown terms as the drawdown pot during the bridging period. Throw in some amount of likely inheritance as extra security and I’d hope I don’t need to worry too much about whether 4% is too risky or not!

Time will tell on my strategy but over the years I have got less and less attached to a key FI date, FI figure etc. It’s more about the broad position I will hopefully be in than rather than exact amounts/specifics. I used to obsess over charts and compound calculations. I still use them of course but more loosely now. I seem to be receding fully into the armchair as the big armchair investing fan I am hehe.

@DavidV – Interesting! Linker yields are looking hot too.

@TheFIJ – Sounds like a very sensible approach. It’s all about the contingency! I’ve become more relaxed too – about spending and investing – despite the contrary signals this article sends 🙂

@TA/David: Do the high annuity rates and yields concern you at all?

@Chris (57)

Unlike many, I have a soft spot for annuities. I do already have a small annuity, bought when rates were much lower because of a technicality with a Section 32 DC pension that gave me enhanced tax-free cash. However, I am lucky enough to have a DB pension and New State Pension with additional Protected Payment. With fiscal drag and high interest rates my income from some unsheltered cash and equities has brought me, when added to my secure income, perilously close to to the HRT threshold. I therefore have no headroom to annuitise any of my SIPP. Without this constraint though, I would be very tempted to take advantage of the current high rates. I have no dependants.

@Chris – It means more of the country’s budget goes on servicing debt so that’s not ideal. Taxes could rise, more cuts to services, evaporating fiscal headroom. I’d rather we didn’t have a looney in the White House, a maniac in the Kremlin and the Government could invest in restoring growth. Alas…

Thought others might find this tool handy for rough estimations of SWR.

https://filiph.github.io/unsure/

@dearieme (#2) @Chris (#52)

One aspect of the ‘annuity puzzle’ is the perceived early death problem (often couched as the ‘being run over by a bus immediately after signing the annuity paperwork’ problem). One practical solution is to extend the guarantee period (guarantees to about 90yo or so are available in the UK). While this has a significant effect on the payout rate for a single life annuity, it has less of an effect on the payout for a joint annuity. For an RPI annuity, a sufficiently long guarantee period tends to reduce the payout rate to the equivalent of an inflation linked ladder (without the faff of building one). For those interested, I looked at the effect of combining annuities with portfolio withdrawals in a paper “Using Lifetime Annuities to Increase Retirement Portfolio Survivability” (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4289339). I also wrote an analogous paper on the effect of bond ladders (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4256534).

Another aspect of the puzzle is whether the retiree actually might actually need an annuity or not. One factor is a comparison of expected expenditure against any other guaranteed income and the likely income from the portfolio. For example, a single retiree with SP (£12k) and average sort of pot of £100k (implying an inflation linked withdrawal of £3k or so) might be happy to go with SWR (or any sort of withdrawal strategy) since portfolio failure would only affect 20% of their total income (i.e., 3k out of 15k). A retiree with a pot of £500k and an implied withdrawal of £15k is risking a significantly larger fraction of their income (i.e., 55%, 15k out of £27k) using portfolio withdrawals and might want to annuitise to shield a larger fraction of their income from future markets. Conversely, if the retiree has a £3m pot but is content with a total income of £43k (i.e., PLSA, ‘comfortable’), the subsequent withdrawal rate of a shade over 1% (to provide the £31k top up to the SP) should be sustainable in all but the most extreme of conditions. The suggestion that it may only be middle income retirees who would potentially benefit from annuities is not new, although I cannot find the paper now (I think it was one of Blanchett’s). I did look at the effect of the size of existing guaranteed income to portfolio size for a variety of UK scenarios in “Supporting Retirement Expenditure Using a Combination of State Pension, Investment Portfolio, Bond Ladders, and Annuities”

(https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4245681).

In terms of annuity risk, the advantage the UK has (over Greece for example) is that we hold our debt in our own currency and either more money or more debt can be issued (with deleterious effects on inflation, debt servicing, and a visit from the IMF). AFAIK, most defaults have occurred where debt was held in a foreign currency (e.g., Greece had no control over the Euro) or extreme events (like losing a war, revolution, etc.).

@TA (#45)

My advice (having spent a couple of months last year on this) would be not to go down the rabbit hole of Monte Carlo simulations since there are a number of questions that are quite difficult to answer, e.g., what shape is the distribution (log normal is commonly used, but there are advocates for other shapes too which capture possible tail events ‘better’) and does ‘reversion to mean exist’ or not (using the standard deviation test in Siegel’s book, for annual data it is quite possible that reversion to mean is just an artefact of random data, while for monthly data reversion to mean is less likely to be an artefact) and how can it be modelled? As well as the problem that the frequency of extreme events is very sensitive to the means and standard deviations chosen.

Sorry for the usual long post.

@Alan S (#61), @TA, etc

Re Monte Carlo simulations. I too have been down that rabbit hole – and built my own tool from scratch! I did actually learn quite a lot from the experience*; albeit it was a long time ago (>10 years back) and possibly the most useful stuff was about stochastic modelling in Excel without using any [3rd party] plug-ins, VBA, or other code! I will never forget being dead chuffed when I managed to re-produce (IIRC to the second decimal place – yikes!) some results from a Pfau paper.

But, in reality SWR is just data mining – and IMO it is definitely over-sold. It is not the only approach to de-accumulation; and nowadays there is a tool/method to help you understand your preferences amongst the deaccumulation options (see e.g. Retirement Income Style Awareness (RISA)). In that sense I heartily agree with Alan’s observations about whether annuities are required, and, if so, where they may best fit.

The very best paper I found if you want an overview of the pitfalls with MC is: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2548651

IMO Patrick C is another one of the good guys – although for some reason he does not seem to merit many mentions!

*a really odd artefact is that as you crank up the confidence required the money needed grows very very rapidly and very quickly outstrips that needed to buy an equivalent annuity even back in the days when they were horrendously expensive cf today

@Alan S (#61), @TA, etc

Re my asterisked point in #62, see also: https://www.aacalc.com/docs/cost_of_safety

@Eddie – cheers!

@Alan S and Al Cam – Thank you for your thoughts on MC. I’m even more put off than I was 🙂

@Al Cam many thanks for posting the link to aacalc article. From their I found aacalc has now been superseded by Aiplanner (https://www.aiplanner.com/)

Not for the faint-hearted, US focused, and laced through with subjective assumptions but(!)…

a) looks to have a model of investment returns and inflation that reflects current market conditions, and

b) the output is just the sort of thing I had in mind that Monte Carlo simulation might offer with distributions of outcomes including “sustainable” annual withdrawal amounts, and pot size bequeathed to the estate.

Sustainable in inverted commas as it’s got a dynamic withdrawal strategy and asset allocation built in as the default. I couldn’t immediately see what rules it’s following for withdrawals or how to override the withdrawal strategy (you can force a lower equity allocation). Having said that the code is available on GitHub and looks mostly to be written in Python. So could probably peer under the bonnet if so inclined!

@Prospector (#65):

No worries.

Most of the work in this space originates from North America* (mostly US & Canada). IMO, Gordon I is another good guy (who is also rarely mentioned, see #62) that has been doing good stuff in this space for years!

OOI, do you plan to lift the bonnet on AIPlanner?

*@TI/TA:

H/T to @M (and the few remaining others) for bringing on the UK aspects!

I’m approaching 57 and have been “retired” for approaching 24 years, with perhaps another 30-35 (or more?) to go….

The only withdrawal method that made any sense was a variable, amortisation-based, approach: adjusting spending in accordance with portfolio balance + future expected portfolio returns.

I use a simple spreadsheet with the PMT function and a (conservative!) blended real return guesstimate for the assets held (eg. from estimated equity, bond, cash, other real return estimates, but very KISS).

As assets fall in price, their future real return guesstimates rise a bit, taking some of the sting out of falling markets’ impact on the withdrawal amount. Also, a chunky allocation to cash dampens portfolio (& thus withdrawal) volatility somewhat, and indeed the portfolio has “lower volatility” as an objective, since a less volatile portfolio has greater utility if withdrawing from it (mathematically).

SWRs are a useful guide when accumulating, but IMO less useful as a practical real-world tool when spending your hard-earned across the years…

The complaint about variable withdrawal methods, such as my amortisation approach, is that variable spending can be tricky for people to live or budget with, but we were self-employed people used to lumpy income streams, or drawing money in chunks as divis rather than as steady salaried people, so this is not a problem for us.

Our approach is pretty simple – the spreadsheet can be knocked up in little time – and easy to understand. Because you’re always course correcting a little you’ll never be too far off course.

@Charley Hay (#67):

Re: “The complaint about variable withdrawal methods, such as my amortisation approach, is that variable spending can be tricky for people to live or budget with, but we were self-employed people used to lumpy income streams, or drawing money in chunks as divis rather than as steady salaried people, so this is not a problem for us.”

I agree; albeit from the opposite side. I was salaried all my life bar a gap of just over a year between jobs*. When I finally pulled the plug, I lived without any form of salary or pension for over 6 years. I never really got accustomed to doing this – although I di learn a whole load of things – and not all of them in areas that I expected! I started my DB pension a couple of years back** and just feel happier about it all now – although mathematically there really should be no difference. Odd things us humans!

*which did not prepare me anything like as well as I though it might have for my much longer period without any salary/pension.

**somewhat earlier than originally foreseen

@Charlie: I think the approach you outline, and the comment about SWR being useful during accumulation, but less so during drawdown makes a lot of sense to me. I do think the harsh reality is that (annuities aside) there is just no certainty in these things at the end of the day.

Receiving regular predictable income will condition us to rely on regular predictable income. So the longer the period that someone has spent in salaried employment, enjoying a predictable monthly or annual income (perhaps 4 or 5 decades?), the harder you’d naturally expect it to be for them to adjust to having an unpredictable income stream once retired.

SWRs seem a bit of a pretense though, offering the prospect of predictable income but at the risk (cost!) of perhaps massively underspending over many years if things happened to go very well, or running out of money if things went really badly.

I can’t imagine anyone has ever *rigidly* followed a SWR strategy over a lengthy retirement, so I see it more as a modelling tool to gauge progress during accumulation, but not necessarily as a tool that you’re actually going to rigidly follow once you’re at the pointy end and begin drawing down.

At this point – actual retirement – being inflexible in your income and spending approach seems a bit churlish, almost inviting the investment gods to frown down upon you, and I don’t think many people would actually be inflexible if their investments were obviously performing particularly well or particularly badly.

Much of the focus, understandably, with SWRs is on trying not to run out of money – no fun once your human capital is depleted! – but if you’re lucky enough to enjoy favourable investment returns, an SWR approach risks heavily underspending.

Variable / amortisation approaches help ensure you neither run out of money as a result of a bad sequence of returns, or vastly underspend (or undergift) in the event of very good returns. NOT linking portfolio withdrawals to portfolio returns – to some extent or other – just seems unwise. I think the key question is over just how to perform that linkage, as there are various methods, with my preference for a KISS method that’s simple to understand and implement and doesn’t *depend* on complex 3rd party tools to implement (unless of course someone wants all those bells & whistles, then that’s fine).

@Charley: I think I generally agree with your comment above. Can you describe your own drawdown approach in more detail? What do you actually do in order to determine how much you get to spend each year?

Has anyone been using Allocate Smartly (allocatesmartly.com) to get a higher PWR? This is a brilliant website that uses tactical asset allocation (so not for the buy and hold folks). It yields a much higher PWR because you can dramatically reduce drawdowns by simply using a system to reallocate your portfolio as economic regimes change over time. This seems a sensible compromise between the risks of buy and hold as a strategy, which makes sequence of returns risk a massive one for retirees, and active trading which may or may not be using a logical, mathematically proven formula for improved expectancy in investing. Worth taking a serious look at for those planning to live off assets and wanting to mitigate drawdowns to maximize withdrawals without risking their portfolio.

My Investment spreadsheet has a Withdrawals sheet with a bunch of inputs for (conservative) guesstimated asset class real returns:

eg.

– Expected real equity returns

– Expected real “bond” returns

– Expected real cash returns

(you could add more of the above buckets depending on what you own and how simple you want to keep things; I do own other asset classes but still just assign them to these three buckets so as to keep it very simple)

– Number of years I reckon I’ll stay alive for [N]

– Any legacy sum I wish to leave at the end [L]

I then “assign” my portfolio holdings across those estimated real return buckets to determine how much (portfolio %) lies within each bucket, so that a weighted average expected real return for the whole portfolio can be calculated [R]. NB if I have anticipated cash costs coming up which’ll consume some of the cash on hand, then that anticipated expenditure is deducted from the cash (ie. assumes it’s already been spent), and from the total portfolio value [P].

It’s then just a case of plugging the numbers into the PMT() function:

This year’s Withdrawal W = -PMT(R, N, P, -L, 1)

…I think, which I’d use as a guide for the maximum withdrawal to take.

I also have some What If? input fields so I can quickly see what a X% drop in equities, say, does to this number, and it’s easy to change the expected real return guesstimates, which by default I have as prudently low numbers. Obviously, the nearer to zero are these guesstimated real returns, the closer your withdrawal calc will be to a simple (P-L)/N.

I think the key thing with this type of approach is that you’re (re)calculating withdrawals based on your *actual* portfolio value, not its *initial* value as with standard SWR approaches. So if your real return estimates are too ambitious, with your actual portfolio doing much worse than guesstimated, you’ll be continually getting course corrected, which should help limit how much damage you do by spending too much, albeit at the cost of seeing substantial drops in withdrawals. And vice versa, if your portfolio performs better than anticipated, then you’re getting a clear signal you can raise your spending. IMO any sensible withdrawal method needs to have some nod towards incorporating current portfolio value, and not doing so is just a bit bizarre/imprudent/reckless.

One additional point: for the behavioural benefit, I use a Cash/Spending Buffer, sized as a multiple [M] of the annual withdrawal [W] amount calculated above, so if the portfolio performs well, the Spending Buffer automatically gets larger (via me top-slicing investments to fund). In the event of subsequent portfolio declines, causing W to fall, this means I end up with an oversized (more prudent) Spending Buffer, able to now cover more than the (new, lower) M*W. This is helpful, since in my experience living off an investment portfolio, behaviourally you can never have too much cash to hand in the event of a larger market (& portfolio) decline.

@Charley Hay (#70):

Re “Receiving regular predictable income will condition us to rely on regular predictable income. So the longer the period that someone has spent in salaried employment, enjoying a predictable monthly or annual income (perhaps 4 or 5 decades?), the harder you’d naturally expect it to be for them to adjust to having an unpredictable income stream once retired.”

Whilst I see where you are coming from, I think (at least in my case) there is possibly more going on. I use a floor plus upside* approach so I did have steady annual funding (prior to starting my DB) and did not thus experience the variability implied by an SWR approach. The only material difference being I “paid” myself c. annually rather than monthly. Not sure why but the monthly DB pay check just somehow feels better, even though our Pot has still not exceeded our all-time peak point (in real terms) that it reached during those first six years. It has come close, but like most folks is currently going a bit backwards. But somehow , to date at least, this does not seem to be bothering me too much. We also seem somehow more free/willing to spend nowadays too. Seemingly somewhat odd – but just my experience.

*with the vast majority of foreseen spending needs (up to planned DB start) locked in prior to pulling the plug; and we consistently under-spent in those early years too

@Talane #72: I’d caution against too much reliance on any back test or modelling tools for TAA.

Spent a decade on and off looking at TAA/DAA systems (including regime rotation and leverage rotation). Well familiar with Allocate Smartly (and many others).

There’s promise in some approaches but given p-hacking, overfitting and backfitting, poor data (with recency and US bias) which hasn’t been cleaned up for earlier years (e.g. move from fractions to decimals in share pricing, accounting for shares that don’t trade), structural changes in markets (e.g effect of passive share increasing, market making changes, HFT, and reduction in number listed companies etc), and with many bad assumptions going into modelling instruments in periods before they started trading (e.g. not properly accounting for financing costs for leverage or changes to spreads and dealing costs); and given also that we could historically have had a quite different sequence of the same set of annual returns and then ended up with completely different CAGR (and Sharpe etc) overall; and then accounting also for the fact that cross correlations are always changing dynamically (and in both predictable and unpredictable ways) – Well given all of that, I’ve concluded (eventually) not to place too much stock in the results of any given strategy – be it TAA or otherwise.

The fairest conclusion is that it’s inconclusive.

Promising, perhaps, based upon one approach to modelling the past which we actually got (which is not the only one which we could have had).

But still ultimately inconclusive.

I’m not dissing variable PWRs and TAA at all here (in fact I’m inclined towards non pure B&H ideas like TAA by temperament), but, honestly, the more one looks into these ideas then the more unclear, nuanced and complicated it all becomes.

There might be something to be said for applying Ockham’s razor.