Ladies and gentlemen, for your edification (maybe) and entertainment (that’s pushing it) there now follows a readable piece about risk tolerance

You know, that oh-so-elusive trait we’re all supposed to account for when determining our asset allocation?

(Yeah, ‘course we do.)

How much pain can you take? How much BS? Risk tolerance is a similar deal. It’s your ability to bite down on a metaphorical plank of wood and endure when your portfolio is shedding pounds like a slimming club champ with the runs.

At some point on the voyage to the bottom of the market, people can snap. They sell out of their sinking assets to staunch the losses. It’s like pushing passengers off an overloaded life raft. In a state of panic, you’ll try anything to stabilise the situation.

When you’ll snap – at 20% down, 50% or 90% – that’s the breaking point that risk tolerance attempts to predict.

Because, like your offed life raft buddies, those losses can come back to haunt you. Losses equal permanent damage if you sell, but are usually only temporary setbacks if you can hang on.

Calculated risk

Risk is the key word here. By holding on, you’re taking the risk that your assets may never bounce back – or may even suffer greater losses – for the chance to reap the rewards that should come if and when the economy recovers.

It’s this trade off between risk and reward (or pain now for pleasure later) that makes equities worth investing in.

Their S&M qualities have brought historic rewards of 5% a year to investors in UK shares, versus just 1.6% for the playful spank of bonds and 0.9% for the soft tickle of cash.

This graph shows the sort of stomach lurching dips you might have to endure in one year of holding equities compared to bonds and cash:

Pretty, but what does it tell us?

- Based on previous experience, in one year you might see your equities go down nearly 60% in real terms 1 compared to less than 40% in bonds and a 20% decline with cash.

- On the positive side of the line, the scope for a bigger win from equities is the reason why we’re prepared to accept that chance of the loss.

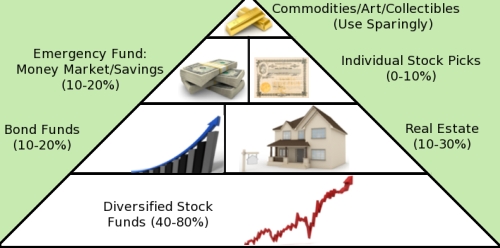

Passive investing thought leader Larry Swedroe has previously published this table as a rough rule of thumb to help you keep your equity allocation in line with your pain threshold.

| Max loss you’ll tolerate | Max equity allocation |

| 5% | 20% |

| 10% | 30% |

| 15% | 40% |

| 20% | 50% |

| 25% | 60% |

| 30% | 70% |

| 35% | 80% |

| 40% | 90% |

| 50% | 100% |

The non-equity part of the portfolio goes into intermediate or short domestic government bonds.

There are a couple of modifiers to the above idea.

- How much risk do you need to take?

- How much risk can you afford to take?

The need for risk

How much risk you need to take depends on your chances of achieving your investment goals with the money you can invest and in the time you have left.

If you need to average 5% real return per year to hit your magic number over the next 20 years then you’re only going to hope to get that from equities.

But if you can tick along at a slower growth rate of say 2% then you can put more of your money into steadier government bonds. Even if you feel like you could take more risk, there’s no actual need.

The lifestyling technique is an example of this, whereby you ease off the equity pedal and press on the bond brake as you near your goal. You do it for the same reason you ease your car into the garage slowly rather than at 60mph to get parked that bit quicker. The opportunity is not worth the risk.

Similarly, if you’ve hit your target then there’s no need to take any risk at all. The difference a few extra grand makes is nothing in comparison to the devastation most would feel if their wealth halved when they’d achieved their goal already.

Even if you can watch your portfolio plummet 50% and feel nothing (What are you? A psycho?), you only need to ensure your portfolio keeps up with the cost of living once it covers your outgoings.

The ability to take risk

How much risk you can afford is a function of how vital your portfolio is to your future well-being.

If your portfolio will be the mainspring of your income during retirement then you can’t take as many chances as someone who is also expecting plentiful support from direct benefit pensions, inheritances, passive income and so on.

Equally, if you’ve amassed a pool of wealth to make Smaug jealous then you can afford to throw caution to the wind a bit. Like Warren Buffet’s passive portfolio, the chances are that you could still shower in champagne even if a huge chunk of your assets went walkies – simply because you’ve got more than you can ever spend anyway. Dream, dream.

Once your essential needs are covered then, theoretically you can stick the rest on the horses and it won’t really matter. In reality, you’re probably investing for future generations and hope to leave a larger legacy by investing in equities.

The other dimension to your ability to take risk is income stability.

If you lost your job and would be forced to liquidate a portion of your portfolio to cover your expenses then you should take less risk than someone who’s backed up by a large emergency fund, a hefty redundancy payout or income insurance.

Remember you’re most likely to lose your job in a recession at the very moment that equities are being pounded, too.

If your job is very stable (perhaps you’re the Queen) then you can take more risk than someone who’s liable to be P-45ed at the first sign of a slowdown.

Risk management

Your chosen asset allocation will likely be a muddy compromise between your estimated risk tolerance and your need and ability to take risk.

The truth is that many of us are in a precarious situation. We need to take risk if we’re ever to retire but Plan B looks pretty sketchy if Plan A proves a train wreck.

In this instance give your risk tolerance the casting vote. You have an August snowball’s chance of reaching your goals if you flip out and sell during a downturn, so staying within your risk tolerance is cardinal.

But how can you work out your personal risk tolerance? Here’s some handy pointers.

Take it steady,

The Accumulator

- That is, adjusted for inflation[↩]

Comments on this entry are closed.

Spot on. I have seen several investors/friends sell out in various recent bear markets only to miss the rebound. And these were fear-based sales rather than forced sales from the need for cash (due to redundancy or whatever).

I did the same in the 2003 bear market and so understanding risk tolerance is definitely lesson #1 before you even dip one toe into the equity market.

Great article, though I think you could expand on it by digging a little deeper into why people have the risk tolerance they do in future.

For someone with a decent income and a good level of savings/investments already the real risk of equity performance is often extremely limited. For someone who is say 10 years from their intended retirement but well short of their desired position the situation becomes more and more complex. They massively desire the potential upside of equities but can’t afford to take notable losses due to their inability to make up for this in time for retirement. For someone in that situation they need guidance, or to do some research and deep thinking, and in my opinion would be best settling on a strategy where they keep enough money in savings/low risk investments to cover the next 15-20 years, then keep the rest in equities.

The answer is not to look at your portfolio more than once a quarter and automate your purchases

But like most things the simpler the answer more the difficult it is to actually implement

Looking at your portfolio daily or even weekly will just drive you to over-trade in my opinion

In some respects the pre-internet paper based systems were better in enforcing this strategy, because you only got a statement twice a year at most

However the charges levels for these services were generally prohibitive in the current returns environment

Far be it from me to agree with Neverland, but I think this is right.

Some kind of thought experiment — how much could you bear — is never going to work. It’s like looking at the F1 drivers on the TV and wondering why they didn’t clip the apex a little more cleanly: quite simply in that situation you’d struggle to stay in the same county at the track, there’s so much going on. You have to live through a drawdown to know how you feel about the thin metallic taste in your mouth as your forecast income plummets. As retirement holidays in sunny hotels turn to camping in Wales.

So is it just a case what you need and what you can stand? How about how often you look? How often you need to look? If it’s in a pension then you don’t really need to look until someone is going to give it back to you. Who cares what it is right now: you can’t spend it anyway. Less so for ISAs and even less for unshielded investments, but if it’s FI-funds then it’s about looking the other way when you would otherwise be scared. After all: you know that if you a long in a dip, the worst thing you can do is anything at all. Just take another long walk around Pen Y Fan and hope the canvas doesn’t leak.

@Mathmo, whilst I agree with most of your comments, I’d disagree with this. I think any sort of pension (SIPP, DB, DC) should be looked at periodically (say once per year) so that you can review both your progress, and your chances of achieving your intended goals. This would then allow for changes to be made as a result (increase contributions, reduce risk etc, plan to work longer etc). Leaving it until retirement time could be catastrophic.

…however there’s something to be said for avoiding looking at your portfolio for a few weeks/months at the first mentions of a crash

How does one take into account property in asset allocation. Particularly property you live in? is it included or not included as part of asset allocation? I own a property in London and have half my net wealth in this property. if its included in asset allocation (which I think it should) then if you are like me you will not have more then 50% in equities. if its not included then it is possible to have 70-80% in equities but then a huge chunk of wealth is excluded from asset allocation (and unfair for those with of of equity tied to property).

Thank you for your post. One point particularly struck us: “Similarly, if you’ve hit your target then there’s no need to take any risk at all. The difference a few extra grand makes is nothing in comparison to the devastation most would feel if their wealth halved when they’d achieved their goal already.”

We haven’t quite hit our target, but we had originally planned on keeping our 75/25 (equities/bonds and cash) allocation after that point since we wanted our investments to pay for a long retirement (40+ years hopefully). Yours is a rather refreshing perspective on whether we NEED to take the RISK. Of course, we need to weigh this perspective against the idea that there is no longer any such thing as a “safe withdrawal rate,” but it’s good to consider all these options.

How does one take into account property in asset allocation: I suggest that you include that part of its value that you are prepared to realise by e.g. trading down or equity release.

I am In the position of living off my portfolio, I arrived age 49 at FI in late 2007 with a very heavy bias to equities and then saw a drawdown of just under 50%, not the first heavy market fall I had seen but dividend income held up well and income from a commercial property rental and some cash meant that I did not expect to starve and the heavy market falls actually provided investment opportunities and thus I ended up well ahead of where I started.

Presently I am around 75% equities and 25% property excl the house I live in. My cash buffer is less than I like but a recent property purchase a reluctant lender used up a lot of cash.

Banks hate people who don’t work……

I therefore fit the position that I don’t need to take risk but feel I can afford to, whilst I don’t see myself as a risk taker I have confidence that I can afford to sit out a protracted downturn and not care. This might be a mistake of course but if you can disconnect and see the value of your portfolio as akin to Monopoly money then it is much easier and more likely to be profitable.

The finametrica type risk tests are very useful, I was very surprised to find myself in the riskiest .3% of the population and equally surprised to find out how risk averse two younger relatives were , at their age I would have felt there was so little to lose and so much to play for.

Know thyself is very important , one must sleep well!!!

I’ve been retired for a year. My asset allocation is currently 70% stocks, 10% commercial property fund, 10% bond fund, 10% cash. I admit that I felt glum during the recent plunge in stock prices. It got me thinking that I might have to rejoin the workforce within a few years. Still, I never seriously contemplated selling any of my stocks. In fact I bought more stocks in January and February using cash I’d put aside for buying opportunities. I reminded myself that as long as I can maintain a cash buffer for living expenses I should concentrate on the income potential of stocks and not worry too much about fluctuating capital values. As I’m in my forties I know that I can still get a job if I have to. In my seventies it would be a different kettle of fish of course.

> How does one take into account property in asset allocation.

If you are living in it in retirement, you don’t. Because observation shows very, very, few people settle into retirement and then choose to downsize. There are just too many memories and you’re just too settled into it, hence the classic stories of the old biddy rattling around in a big home, and all the ads for stairlifts. If you downsize before or at retirement, then fine, you match your proprty exposure to your needs.

You do draw an income from your property. It stops you paying rent. Downsizing is the way to reduce the amount of capital you have to hold to avoid paying rent on somewhere far too big for you.

with regards your home value, it depends what you are measuring. If you are measuring the income you need to retire, and this income doesn’t include the market rent you would pay for your home, you wouldn’t include it (unless you plan to release equity in some way). Otherwise you are incorrectly stating your risk level for the income you are specifically building up. Net worth, yes include it but this isn’t useful for the specific goal of creating this income source.

There is also the question of property risk. It could be argued property is in a major bubble and could be more risky than shares…….

This is a really usefull article to explain risk tolerance. The view I took was to accept a high level of risk (full equity exposure) when investing every month / year on the basis of the averaging argument. Then ten years to planned retirement age to begin to derisk volatility by gradually switching away from equities until a 50% allocation is reached at the retirement age.

The plan being that I will have steady income with little volatility in retirement. Well that’s the plan!

The arguments about reducing risk as you approach retirement apply best for conventional retirement in your late 60s. If you want to retire at 50, your portfolio needs to be more aggressive to cover the extra 15 years, but you can take on more risk because you have more time for markets to recover.

In my financial modeling I have 3 income phases: early retirement, high spending as I tour the world, low as I become a home-body, and very high again at the end as I pay care home fees. I think you can plan to release some of the house equity in phase 2, and all the rest for phase 3.

In risk terms its a good idea to plan you don’t need to downsize for say 70% of scenarios, downsize for the next 20%, and become a complete renter for the worst 10%

What is really hard is balancing the optional costs of phase 1 with the extremely variable costs of phase 3, especially with Altzheimers meaning it may not be “you” that you are supporting. How do you compare 1 year working with 6 months traveling with 3 months drooling? Or the memories you have at each phase?

In the same way that you run Monte-Carlo simulations of market outcomes, you need to run simulations of your future health, and its the intersection of the worst 20% of financial outcomes with the highest 20% of spending scenarios that decide your risk profile, as then its a 4% chance of throwing yourself at the mercy of the state, That’s the kind of acceptable risk for me.

@Jonny — you are of course quite right. You also need to know when to rebalance if you aren’t in a single fund. I check fairly frequently to see if I am allowed to swap assets around. But when work gets busy I know that I can ignore it for as long as like. I always do a quarter-end summary for my portfolios.

I will say this — shrinking the whole shebang into a single number (forecast retirement income) makes equity movements seem a lot less dramatic and nicely works with the “am I on target?” indicator.

@John B I can understand your strategy, and it’s easy to appreciate the complexity in comparing a fairly predictable income requirement for phase 1 and the hugely variable cost in case 3.

For me the 50/50 split gives a simple balance of risk and reward, and like below, for example allows sensitivities to be considered.

https://www.vanguard.co.uk/uk/portal/investor-resources/learning/tools

But it is all complex, for sure!

How many investors do you think are able to comprehend their ability to tolerate risks? I believe very few. In fact, you get to know yourself in the process of investing itself. It takes several mistakes to contemplate..

@Mathmo, yes, the single number is a good idea – I hadn’t thought of it as a psychological dampener on large equity movements.

There is a good downloadable spreadsheet template available for logging and getting to this figure, in Thriftygal’s blog post here: http://thepowerofthrift.com/build-financial-independence-chart-updating-thriftygals-charts-october-2015/

I must confess despite budgeting obsessively all my adult life, I’ve never really concentrated on estimating passive income or logging my spending.

I used some of the ideas in that post/spreadsheet to put together my own, to log all our monthly income, outgoings, debts (aka Mortgage), assets etc, and produce some nice charts (again inspired by Thriftygal’s post) for these monthly figures.

I’m hoping this will encourage us to work towards reducing the expenses line, and increasing the passive income lines until they miraculously cross over, as which point our goal will have been reached. 🙂

Similar sentiments for my assets vs debts chart too…

Warren Buffet’s passive portfolio. I’m sure Warren Buffet’s 10% short-term government bonds serves as an emergency (illness, etc.) fund for his wife .

@Jonny – good article, thanks for the link. Thriftygal’s methodology seems more appropriate for people nearing retirement I think, because current expenditure at age, say 33, probably not a good predictor of expenditure required in retirement…

…also, isn’t there an element that you can ‘spend up’ to any given income…so if in the accumulation stage and its looking like you can afford two nice holidays a year in retirement time to lock on and make it three ?

@Planting Acorns, for me personally (currently nowhere near FI/retirement) the methodology is still a useful indicator.

First, I know I need to keep the gap between current income, and expenditure as large as possible. If a pattern emerges that the lines are closing in, I should be able to visually see this, and (hopefully) react quickly.

Also, if I can get my projected passive income above the expenditure line too, I’m laughing (because that currently covers my mortgage payments, child costs etc), so would be more than enough when in retirement (and mortgage free, without dependants etc.). Your right that it’s “not a good predictor of expenditure required in retirement”, though for me it allows me to both aim high (i.e. try to cover current expenditure), and monitor my journey along the way.

@Jonny @PA @Mathmo — I wrote an article many years ago that might be relevant to this discussion, though won’t tell any of you anything you don’t know already. 🙂

http://monevator.com/try-saving-enough-to-replace-your-salary/

With these sort of discussions, it can be worthwhile/prudent asking again :-

1. What is Risk?

2. Is (downside) risk constant, regardless of valuations?

The Volatility = Risk assumption is a very convenient shorthand device to enable maths to be applied portfolio construction, but may have it’s limits, the article usefully draws us back to the very basic and timely reminder of thinking seriously about risk. V=R is not to be discarded without careful thought; as it is difficult to come up with a useful/powerful alternative.

For those who regard Volatility = Opportunity, then if stocks had zero volatility, where would be the opportunity.

As to the second question; debate will as ever continue, but tentatively suggest market PE of 24 and market PE of 6, do not hold the same risk levels.

@Johhny @TI

…I guess your current income is as good a starting point as any for determining what income you require… Although I’m not convinced I’d need an income as high as my current one on retirement…don’t get me wrong I don’t have Brewster’s millions type money…there’s just a lot of things I do now I won’t need to – buy shirts/ suits/ etc/ save/ mortgage…

Thanks for the comments all, haven’t had a chance to respond – nightmare week at work.

Great to see comments from so many people who’ve hit FI / are on the cusp. My eyebrow was raised at 70%+ allocation to equities though. I imagine I’ll be 40 – 50% equities in my first FI decade to avoid a bad sequence of returns forcing me back into work.

Re: not looking at portfolio, it definitely helps but at some point you gotta look. I think that nothing helps like education. Knowing how prone the market is to mania helps you deal better with its mood swings. This is a great piece from the Irrelevant Investor on the bipolar nature of investing: http://theirrelevantinvestor.com/2016/01/20/whats-going-on/