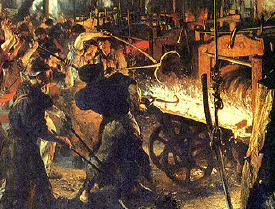

People have a fetish for smelly, bloody and dangerous occupations where the returns are poor and the competitors numerous.

No, I’m not talking about the British kink for dominatrices.

I mean the warm feeling the public has for manufacturing – and not even the slick, highly-skilled factories that we have in the UK and the US, but the grubby assembly lines that migrated to China.

It’s enough to make William ‘Dark Satanic Mills’ Blake turn in his grave.

The manufacturing myth

The Register recently published a perfectly reasonable article about the UK’s manufacturing sector. It explained how British manufacturing output has actually more than doubled in value since World War II, as shown by the following graph:

The graph is the Index of Production, from the Office for National Statistics. It is adjusted for inflation.

The article’s author, Tim Worstall, explains that the myth of British manufacturing ‘decline’ is so potent that reality is shut out of the conversation.

He writes:

Woe unto us for we don’t make anything any more. We’ve given up on manufacturing and that’s what ails the UK economy. We must therefore invest heavily in a renaissance of making things that we can drop on our feet and all will be right with the world.

You don’t have to be all that much of a newspaper fanatic to recognise that mantra: it’s been repeated so often that it has become the received wisdom. We even have politicians advancing ideas about how we might manage to achieve the desired outcome.

There is, however, only one teensie tiny problem with the whole idea. It ain’t true.

Tim’s article covers most of the important points:

- We’re generally making higher value things – a good thing.

- We employ fewer people to get more output – a good thing.

- Since manufacturing output hasn’t shrunk – in fact it’s grown – then if it only makes up 12% of the economy compared to a peak of nearer 50%, this means other aspects of the economy have grown even faster – a good thing.

Great stuff. Yet what’s Tim’s reward for debunking one of the most potent myths in the UK? A slap on the back? A knighthood?

No, a comment thread on his manufacturing article full of the usual hysterical hand-wringing, with some gratuitous name-calling thrown in.

The case for more manufacturing

The arguments for manufacturing are always the same:

- Manufacturing would protect us from recession

- We should make things people actually need

- The service sector isn’t the real economy (a country can only employ so many hairdressers)

- Britain was once the workshop of the world

- China will win, because the Chinese work harder at real jobs

Manufacturing fans may protest that their arguments are slightly more sophisticated, but that’s essentially what it boils down to.

Are they right?

What do you think?

Manufacturing would protect us from recession

This is just self evidently wrong. If nobody is buying anything then nobody wants your manufactured products, and it’s much more expensive to mothball a steel factory than an office.

Besides, Germany and Japan are the favourite examples of the pro industrialists (no list is complete without the roll call of Sony, Seimens, BMW, Yamaha, Bosch, Volkswagen and so on) yet Japanese and German GDP fell by 5% in 2009 – far worse than the US decline of 2.4%, and even worse than the UK’s 4.8% decline (Source: OECD).

We should make things people actually need

Have you actually been shopping recently for things people actually need?

My dad used to regularly service his prized woodworking tools. Now a decent hand saw costs a virtually disposable £6 at Amazon. A well-reviewed toaster

is £12.38. A Samsung 19-inch Widescreen LCD TV

costs a giveaway £169.

The whole reason people like me can save up so much money is because ‘the things we need’ are cheap to buy. You don’t have to work for three months to buy a fridge anymore. The same downward pressure on cost is evident from cars to off-the-shelf helicopters.

Making stuff is a bad business. Even that TV could likely be sold for £50 from the Korean or Chinese factory it rolls out of. The rest is the ‘worthless’ value-added frippery that people decry.

The service sector can only employ so many people

A.k.a the ‘Britain only needs so many hairdressers’ argument.

This is basically a failure of the imagination. Many people don’t understand how a banker or an architect or a journalist adds value any more than a rural peasant in the 1700s understood what happened in an iron foundry.

Worse, they seem to think human civilisation has halted. They’d be the peasants crying out: “Britain only needs so many horseshoes!” without envisaging steamships or railroads.

The promoters of this line of thinking might also be surprised to hear that the service sector in Japan accounts for 75% of GDP. In Germany it’s 67.5%.

Clearly being a posterchild for manufacturing requires great hairdressing!

Britain was once the workshop of the world

This is nostalgia, pure and simple. As a human being I get the emotion, but it’s not relevant as to whether we should be the workshop of the world today.

Where to begin? Aside from the fact that making stuff isn’t great business, there’s also the fact that the sort of raw manufacturing China excels in is dangerous and polluting.

What about high-end manufacturing by smart new robots like we see in Japan and China? Yes, that’s more desirable – and happily it’s also manufacturing that we do here in the UK already.

Britain made 1.4 million cars in 2008. That’s down from the peak of nearly 1.7 million in 1997, but it’s more than we made in 1960 in the final hurrah for the Golden Age of Britain’s car industry.

Also, I hope everyone who is obsessed with us making stuff has shares in the likes of Goodwin, Rolls Royce, Rotork and Renishaw, among many others. Such companies may have factories abroad, but they also manufacture goods here in the UK.

China will win, because the Chinese work harder at real jobs

This is the uber-argument of pining-for-manufacturing lobbyists. They admire the strong back of the doughty Chinese laborer as he sweats under a blowtorch and plays his part in knocking out a £10 toaster.

Such blindly pro-manufacturing men – and they are always men, usually in their 50s and 60s and jaded with the world – may admire the Chinese, but they also fear them.

What will Britain do when China makes everything!

Firstly, the whole reason these countries have taken our manufacturing industry off us is because they are poorer than us. They’re not born with a love of riveting. They’ll simply work for less than we will – and not because we’re (all) lazy either, but because we’ve got much better paid service sector or high-end manufacturing jobs to be doing.

Secondly, even China is losing low-end manufacturing business to the likes of Vietnam and Indonesia.

I’m not sure where the Manufacturing Is All Important lobby thinks this will end? Presumably with Bangladesh and Burkina Faso lording it up over the rest of us with their factories and stuff.

People are afraid of a world they don’t understand

I’ve tried not to be too superior-sounding above. I have family in former industrial areas of the UK, and I am well aware of the painful dislocation the economic shift of the past three decades has wrought.

There’s a frightened voice at the heart of all this noise about the manufacturing industry. People don’t understand the modern world. They don’t see how 27-year old traders on Wall Street can cause a global recession. They don’t understand how everything in their house can be made abroad, and yet they are still apparently richer than the people making it.

You can tell them, as Tim Worstall does in his piece, that agriculture was once 80% of the UK economy, and that if things hadn’t changed they’d still be spending 14 hours in the field digging up turnips, but it’s no good. They have been taught the way the world worked in the past, and they are uncomprehending about the future.

However, my sensitivities only go so far. There’s simply no excuse for the well-paid office workers who frequent The Register’s forums to deny reality by posting kneejerk laments about manufacturing before heading over to read about the oh-so-inessential iPad on Engadget.

(I’m making a leap here and assuming that the 80-odd comments weren’t left by barely skilled factory workers who downed tools just long enough to find a computer to greasily peck out their two-pence worth on).

If people want to club together to buy a low-end industrial sweatshop in Asia, they’ll find they’re cheap and interchangeable. Pool your money guys, and knock yourselves out on an electric toothbrush assembly line of your own.

I’d rather buy shares in the likes of Apple, which sources and assembles cheap, off-the-shelf components in Asia – after adding $399 worth of ‘worthless’ magic to the package in Cupertino, California.

Comments on this entry are closed.

I agree with the general point. I certainly believe that journalism adds value! I liked that one.

I feel compelled to try to give voice to some of what might be driving the other side of the argument. People can see the product generated by a factory. The benefit in this case is tangible. The benefits of journalism? Not so much.

When an economic system fails, as ours is in the process of doing (my view!), people look around for things in which they can place their confidence. Those who are producing things are certainly doing something good. Those who produce thought pieces sometimes are and sometimes are not. There are many acts of journalism that do more harm than good. I think that’s the objection — that we don’t know in which cases these new-fangled sorts of occupations are doing us harm and in which cases they are doing us good.

In an overall sense, my belief is that the new-fangled sorts of occupations do more good than harm. But I can see why doubts are raised about them when the sand starts shifting underneath our feet. We are in the process of moving from one sort of economy to another. To make a successful transition, we will need to come up with better ways of testing when journalists (and all the others) are doing good work and when they are just blowing smoke.

We all have a desire for justice within us. When bad work is highly compensated, it offends that sense of justice. There is a lot of bad journalism bringing in big paychecks today. That causes some people to doubt the entire enterprise (in a bit of an overreaction). Overreaction or not, it’s a reality that those of us who like the idea of the new economy need to grapple with.

Rob

.-= Rob Bennett on: My E-Mail to Dan Riehl, Author of the Riehl World View Blog =-.

The points made are valid ones but don’t tell the complete story, what is left out is the role of hedge funds who take advantage of tax advantages overseas to close down British manufacturing, who take advantage of high property prices in the UK and cash in on the equity when they close British factories and who take advantage of resettlement grants in other countries, having already used up grants here to up sticks and move to greener pastures.

What is also missing is that many of the products are not made by harder working skilled workers but by indented labour, women and their children, if the story behind how some products were produced were known l suspect that many more British people would refuse to buy those goods.

What we need is a standard of “even playing fields” in where British workers could compete; “That goods from the country of origin should pay a fair minimum wage where the workers are adults and have the right to organise and have freedom of association. That the tax regime does not differ widely from most manufacturing countries and gets no hidden government support. That the company manufacturing these goods is not a monopoly or uses leverage in that country to influence the government of that country to it’s advantage. That the country itself has fair laws regarding labour and allows protest or the right to with hold labour.

l am sure that there are more criteria in other countries we compete with which could lead to fairness in trade with the west but at the end of the day it will be up to the public to pressure government, and retailers to conform with their feelings on these issues.

@Colin – Thanks for your comments, though as you’ll suspect I’m bound to disagree.

Nobody likes child labour, but it would hardly stop there – all kinds of restrictions and lobbying would come in. Ultimately it’d just jack up the prices we pay – and as I say for no real gain, as low-end factories are a commodity business that we’re well rid of anyway.

@Rob – The way to test is in what the market pays, and what our GDP figures show. Manufacturing has been declining as a share of GDP for decades in the US and UK, but GDP and standards of living have soared. That’s because the work is real and value-adding. (The slight fly in the ointment is the role of debt and leverage in boosting GDP in recent years, but as I cite above deleveraging has hit manufacturing heroes like Japan and German just as hard – not surprising as they need customers!)

@Colin: point taken about the types of people working in manufacturing overseas, but are they, and their conditions, much radically different from those in U.K. during the industrial revolution? As I understand it consumers in the U.K. happily snapped up the output of our “dark satanic mills” without worrying about the workers’ conditions. Obviously things changed and the conditions in manufacturing improved, but this is also happening in overseas factories too, is it not?

I’m just going to ask a question (please don’t read much into the question… there is nothing between the lines) just because I’m curious about your thought on the matter:

What do you foresee as the future employment opportunity that will make your country (or mine for that matter) great or at least able to maintain status quo?

Thanks for an well thought out article, it was interesting for me to learn some of the concerns you have about the media/journalism in your country.

.-= Money Reasons on: Wealth Tip #4: Invest Money Saved on Food and Other Products =-.

@MoneyReasons – The $64,000 (plus inflation!) question! 🙂

I’m going to duck it and say it’s very difficult to answer this with any clarity, which is one of the reasons people get nervous about the future. In the 1950s, all the bright graduates went into plastics, for instance. Hard to believe isn’t it? People thought plastics were the stuff of the future (which proved true, but they don’t underpin the economy). Similarly, computers were barely in business by the 1970s, and even in the early 1990s I was unusual in having an email and one of the first web browsers.

We just don’t know what will be important, which is why having a flexible economy that can get rid of unproductive sectors (like low-end factories) is important – with I believe sensible safety nets that mean workers with redundant skills aren’t tossed on the scrap heap but equally are soon retrained and don’t live off the state for ever.

Great question, anyway – I’ve thought of a new blog post about future careers on the back of it, so thanks!

Great presentation! I think you may have convinced me that you are right about the low-end factory jobs, I’ll have to chew on it a bit…

I guess the key then it to be cognizant to the opportunities that present themselves, and capitalism on them as quickly as possible.

Thanks for the great reply, and good answer! 🙂

.-= Money Reasons on: Wealth Tip #4: Invest Money Saved on Food and Other Products =-.

Are we simply not just talking about the evolution of all societies? From manufacturing to services due to the competitive advantages and tastes of nations?

Everything is rational, and once that is accepted, everything ALWAYS makes sense.

Allan; yes the British empire was made out of the suffering of others, slaves, children and downtrodden workers.

The shame of that exists today in some quarters, l live in a former coal mining village where that knowledge is passed down through mothers milk, we have a thriving Co-Op, a Labour club and miners welfare society. Like most injustices perpetrated on people, no matter how hard the grandchildren of those who were the beneficiaries try to claim that “it was in the past”-people remember

The move from a manufacturing to a service economy is a natural evolution. As a country that tries to emphasize education, we should relish in the fact that the average American employee is qualified to do work above basic manufacturing.

Having said that, the move to service has been precipitated by unions and the minimum wage. Labor often outprices itself.

I think a large part of the motivation is simple nostalgia. People have an unfortunately romanticized view of the past, particularly of how ‘simple’ and ‘wholesome’ life was a few generations ago. People who never had to struggle in sweatshops for decades in order to eke out a living have romanticized the idea of the ‘hard-working, blue-collar man’ and seem to forget that there was plenty to dislike about that life (such as said hard work). It’s similar to what happens with the cowboys here in America; everyone thinks of excitement and adventure, nobody thinks of boredom and having to deal with thousands of smelly cows on a daily basis…

.-= The Amateur Financier on: Book Review: Master Your Money Type =-.

@TAF – Interesting comparison to the cowboy lifestyle. It’s true, people pine there for a time that was both dangerous and lawless, or else just drearily repetitive and hard. We are nostalgic for an idea of how things were, not for how they really were. Thanks very much for you thoughts!

Mrs @DH & I recently found a 1981 Times newspaper lining the inside of one of her mother’s cupboards. It showed an advert for a goods sale at Rumbelows, at electric goods store that was the Dixons & Currys of its day (it disappeared from the high street in 1995). Every single item on sale in 1981 cost more on sale then than the full price item could be had 43 years later from the electricals section of ASDA now in 2024. In some cases the equivalent item now is half the sale cost in 1981 and exponentially better (i.e. colour TV with remote in 1981 v OLED 4k smart TV now with a massively bigger screen area and much, much thinner).