Prices for prime properties in some global cities are softening. Commentators tend to put their weak local market down to local conditions – tweaked tax laws, or regional political concerns – but are they missing the big picture?

Bears have lost – or at least not made – untold billions by betting on the end of the bubbly market for assets we’ve seen since the boom began in 2009.

And I’ve been pretty optimistic throughout what’s still being called a “recovery”.

But nothing lasts forever.

Crucially, US interest rates are already well off the bottom.

Continuing low rates in Europe, Japan, and the UK curb will restrict how fast and how far US market interest rates will go. Perhaps the US President will too, with his random Tweets driving fearful money back into Treasury bonds, in turn pushing yields back down.

But with North America’s unemployment now very low and its economy boosted by a late-cycle tax-cut bonanza, it’s hard to see why the Federal Reserve won’t continue to hike its benchmark interest rates in the months and years ahead – a complete contrast to the easy money regime that has prevailed since 2009.

The end to that near-limitless cheap money will surely be felt around the world, one way or another, in time.

Is prime property already rolling over?

Global gains

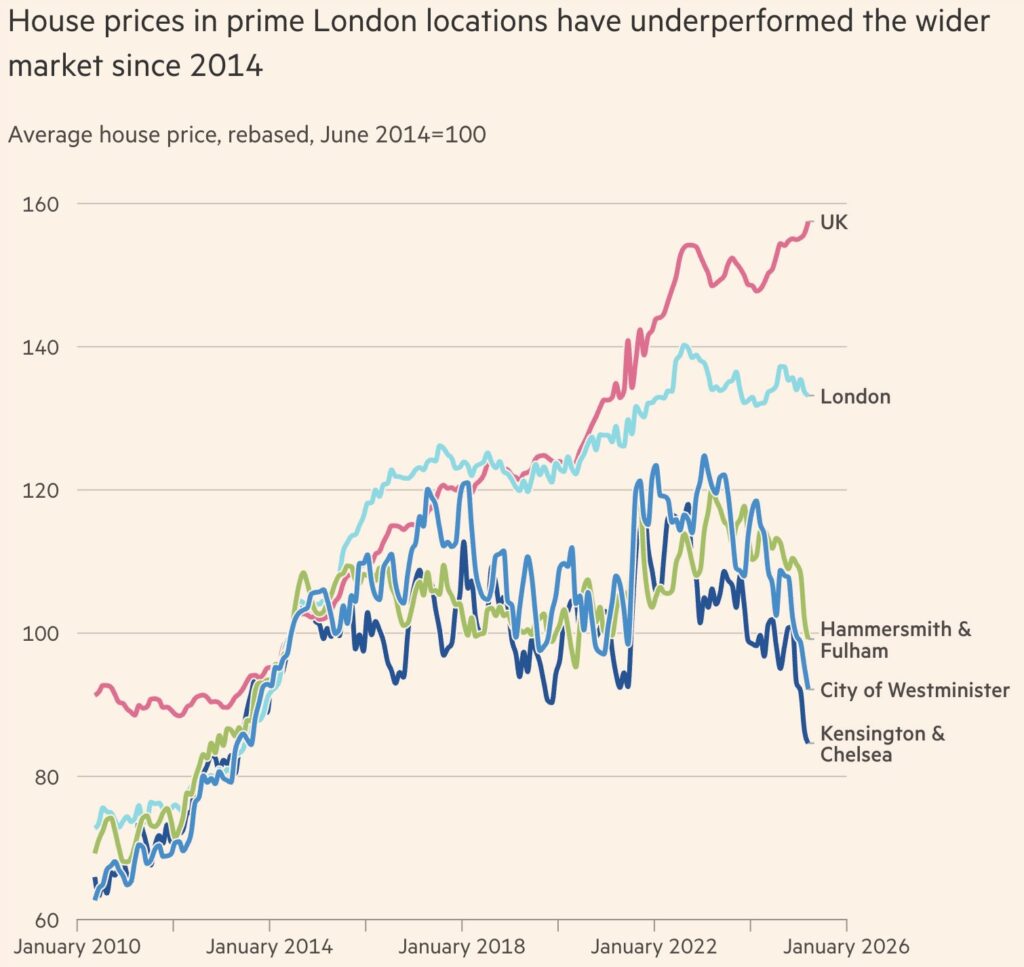

The Financial Times has detailed how global cities have boomed since the crash:

Over the past 10 years, the life-cycles of global cities such as London, New York and Sydney start to look very similar.

They begin with central banks cutting rates; then foreign buyers are welcomed in, prices go up, high-end homes are built, capital appreciation drops and then cities are left with a lot of stock which is too expensive to sell.

The FT also featured a snapshot of how the cream of the global cities had prospered over the past decade:

It’s quite remarkable really.

True, most of these cities had seen high house prices long before the financial crisis.

But few (if any) pundits predicted the house price growth we’ve seen in these global cities in the subsequent 10 years.

The financial crisis involved an excess of debt and speculation in property – albeit more sub-prime properties than Manhattan penthouses.

Property therefore didn’t seem the obvious place to look for a new boom.

But in retrospect, it looks obvious what happened.

By successfully (re)inflating asset prices, quantitative easing (QE) made the rich, richer. And the rich tend to live in global cities.

In the fearful years that followed the near-collapse of the financial system, few wealthy people fancied a move to a far-flung rural town…

London falling

The FT article explains this dynamic in the context of London.

Waves of capital washed into London’s housing market – first from bog standard rich people seeking safety, then from sovereign wealth funds lured in by the fall in the pound, then Russian and Middle Eastern investors fearful of disruption in their part of the world, and finally with a wall of money from Asia.

Already high prices for prime London property hit levels that seemed fantastical. (£140m for a penthouse, anyone?)

When did this start to reverse?

The collapse in commodity prices in 2014 didn’t help. That squished the spending power of Russian oligarchs and Middle Eastern royalty.

Stamp duty changes the same year also increased the cost of buying the priciest homes.

The price of visas were raised. From April 2015, tougher anti-money laundering measures were introduced, too.

All told, the Home Office recorded an 80% fall in the number of foreign investors moving to Britain in the year to 2016.

Then there’s the ugly white elephant – Brexit – which has turned UK assets into the most unloved in the world for global fund managers.

The result? A malaise that has spread beyond Mayfair and Belgravia. London house prices just posted their first annual fall since 2009.

The FT argues London property simply got too expensive. And sure, if London homes were cheaper then perhaps they could have shrugged off some of these headwinds.

Stamp duty might never have been raised so high if the Government hadn’t seen a cash cow to be milked, too. There’s an element of reflexivity to this.

But look at other big global cities. Many of those also seem to be losing their footing. Can it be a coincidence?

Here, there, nearly everywhere

Let’s whip around the world, montage-style:

Re-sale home prices in the Toronto region dropped 12.4 per cent, or about $110,000, year over year in February.

[…] the Ontario government took cooling action by introducing its Fair Housing Policy, including a foreign buyers tax, said Jason Mercer, TREB director of market analysis.

Cracks are showing in the Sydney property market, with prices now falling for the first time over a 12-month period since the boom began.

Manhattan real estate sales and prices took a fall in the fourth quarter, and they’re likely to slide even further this year after the new tax rules take effect.

Total sales volume fell 12 percent compared with the fourth quarter of last year — the lowest quarterly level in six years, according to a report from Douglas Elliman Real Estate and Miller Samuel, the appraisal firm.

The average sales price in Manhattan fell below $2 million for the first time in nearly two years.

Out of the 70 cities tracked, prices dropped in 16 cities month on month including first-tier cities Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen.

It was these top-tier cities which saw the most significant decline in prices.

Shenzhen had its biggest drop in three quarters as prices slid 0.6 percent from the previous year. Prices fell 0.4 percent in Guangzhou, 0.3 percent in Beijing and 0.2 percent in Shanghai, compared to the same period last year.

Granted, these are tiny falls so far. Not much more than noise.

It’s also not universal – Paris and Singapore for example appear to be bucking the trend. Perhaps it’s because they missed out on the prior boom, but anyway if some global cities continue to do well it does slightly scupper my thesis that cheap money is beginning to ebb away, exposing the priciest assets.

Perhaps it is just a matter of froth being blown off. The masses had their Bitcoin frenzy in late 2017. Maybe global property was the same mania for the 1%.

Yet it’s still odd to see prime property falling even as the global economy does better than it has done for years.

Property is typically a lagging indicator, not a leading indicator like the stock market. House prices tend to react, rather than predict.

But when it comes to the end of super low interest rates, perhaps prime property does have something to say about the future?

Prime property is very often bought with cash, not a mortgage. To some extent that might soften the link between property prices and rates – certainly compared to the mass market.

However investment is everywhere and always a relative game.

If the rich can now get nearly 3% from a ten-year US government bond, maybe they no longer want to bother with taxes, estate agents, and getting the windows cleaned twice a month?

It will be interesting to see who reaches a similar conclusion next. The share prices of so-called ‘bond proxies’ like consumer goods giants have already softened a little, but they could have much further to fall if investor appetites truly change, for instance.

In contrast, maybe the cheap-ish, cheer-less UK stock market might finally get some love, stuffed as it is with cyclical miners and banks.

Your next local house price crash: Made in China?

I began writing this article in the snowy miserableness of March, but got distracted by new flat nonsense and never finished it.

And that’s convenient, because this month the IMF came out with research stating that global cities are indeed increasingly moving in sync.

In its latest Global Financial Stability report it found:

…an increase in house price synchronization, on balance, for 40 advanced and emerging market economies and 44 major cities.

Countries’ and cities’ exposure to global financial conditions may explain rising house price synchronization.

Moreover, cities in advanced economies may be particularly exposed to global financial conditions, perhaps because they are integrated with global financial markets or are attractive to global investors searching for yield or safe assets.

I have no firm conclusions to draw about all this right now. My track record of predicting property prices is poor!

Also, before anyone (rightly) pipes up and says that potential house price falls in New York shouldn’t derail your passive investing strategy – I obviously fully agree.

This post is filed in the Commentary section. Most readers own property, too, so the asset class is hardly irrelevant. But acting on the end of the QE-era should probably be left to those of us silly enough to muck about in active investing waters.

To that end, I am Watching This Space.

One of the (less important) reasons why I finally bought a flat in London this year was I could see the market was soggy, and I put much of that down to Brexit uncertainty. Given that Brexit uncertainty should pass, one way or another, it seemed a potentially opportune window to buy.

But synchronized falls for global property could indicate I was mistaken about the role of Brexit. Perhaps the property cycle has turned. We’ll see!

Comments on this entry are closed.

There are certainly big problems selling property in my area (SW London) and have been for the last year. Buyers of prime property just seemed to have vanished. In one extreme case, a friend had to cut the price of her house from £15m to below £10m in order to sell it. In the more mainstream £2m-5m bracket, I know of several people who have tried to sell their properties and have now taken them off the market. They plan now either to stay put or let until buyers come back.

I think a drop in prices is to be welcomed, but the freezing up of the market is not as it impedes efficient use of housing. I agree that a range of factors are responsible for this, but I would say the catalyst for it around where I live is undoubtedly the uncertainty of Brexit. I have long thought that a reform of property taxes is needed – abolish or significantly cut stamp duty and introduce a land/property tax.

I still have my property bear hat on and that’s unlikely to change until the UK housing PE ratio is about half its current level.

Also, on the supply side things may finally be getting going. This is anecdotal, but where I live there are plans for multiple “garden towns” with many tens of thousands of houses expected to be build over the next decade or so (they’re already adding new junctions to the motorway and digging up roads to add in more pipes and cables). Multiply that across the country and the tight supply situation of the last 20 or so years might finally begin to reverse.

Well, I’ll start by saying I was always told that the answer to any question in a headline is always, ‘No!’.

Flippancy aside, I have no idea. I’ve been bearish for years, generally being persuaded by the likes of the CGT and PNL managers, and have suffered for it.

However, I still believe in cycles, and this one has gone on for so long, that the chances are probably increasing that the bears will be right again.

Key indicator is @TI finally bought a flat .. 😉

@PC – I was waiting for that one, it has been mentioned in a previous thread that his entry would undoubtedly signal the top of the market and so it was..

Is it possible that property prices in the world’s major cities appear to move in unison because central banks move in unison ?

It was probably mentioned by me! 😉 As I said in my original post about buying my flat, I have an investor friend who made me swear to text him when I finally bought so he could dump his UK banks and short house builders.

He’s a slight contradiction to the theory of me being the last bear to turn though, as he sold-to-rent years ago and isn’t buying back in…

I’ve been trying to get him to write for Monevator for years actually, as his bearish take is very different from mine or @TA’s, and he’s not got a bad record, for a bear. (I was most impressed when 4-5 years ago he told me he felt that the political wind had changed about house ownership in the UK, and now politicians had sensed that ever higher house prices was becoming a political millstone. He said he thought policy would started change. And so it did, with stamp duty changes, BTL tax changes, etc).

I should get my post on why I bought written, actually, as soon it is going to be seen to be informed by (and may even be tainted by) hindsight bias. Suffice to say that London property has been soft for at least a year, and I knew it (I was actively seeing properties for 4-5 months so it was obvious!)

I didn’t (don’t?) expect say a 20% nominal crash though. I’m a bit less confident now. We’ll see! 🙂

p.s. I say “for a bear” because while in theory one is bullish or bearish about this or that, he is one of the species that is invariably bearish about most things. (Gold excepted…)

The speed of the property cycle appears to have slowed down at the same rate as central banks loosened their policies. But the signs of a peak are accumulating. Adding to @TI dipping in, may I suggest:

– the Harvard MBA offers several real estate investment courses these days, and even has an ‘immersive field course’ called “Boston: Investing in a High Priced World”

– a flat on Countess Road, NW5 (I lived there until 2016) is currently listed at €18k/square meter; we bought in the second most expensive city in the Netherlands last year at €3k/square meter.

To counter the bears though, who believes that central banks will actually persist with rate hikes?

》To counter the bears though, who believes

》 that central banks will actually persist

》with rate hikes?

They won’t. As soon as there is any whiff of serious asset price deflation, interest rates will be back at zero

I think the synchronisation of events is down to globalisation – in that capital is then free to flow [like water with gravity] to the highest returns, hopefully moderated by at least some risk assessment. If something happens to spook the investors, they shuffle asset classes or at least the ratios of their capital within & between. With Trump aggressively kicking off trade wars, the threat of nationalism [several countries now have restrictions against foreign buyers & not just in the form of taxes] might induce wariness of freezing assets or outright confiscation. (remember bank account deposits in Cyprus larger than a certain amount being seized during that punitive ‘bail-in’ experiment …..those affected being mainly Russians funnily enough)

It could be several contributary factors combining to effect a flatlining market that could last years and not necessarily be a bad thing – so mostly just firesales in a place like London as sellers hold out, but leading to a re-balancing of the UK economy as the promising youth increasingly choose cities with a better quality of life instead. I only know SW London, but the number of new-builds that shot up in the last 2-3 years just around Battersea alone had to have an effect at some point. Whole blocks of crappy 1 & 2 storey buildings were leveled to be replaced with at least 10 floor behemoths, the resulting population density must have gone up a log scale. At the time I wondered how all these additional people’s needs would be met, health, education, services etc., when the infrastructure was planned for much fewer.

TI..

even if it does crash 20%, it will come back. Maybe not as quickly as it did this time – for the South East at least (I remember buying in 1990 and taking 6 or 7 years to get back out of negative equity).

Meanwhile at today’s rates you’re probably paying in terms of the interest element less than a rental.

I’m a hobbyist property developer and I welcome the flatlining – it gives predictability. However, I will be more concerned if the market goes down as I’m not even water tight yet. Fingers crossed.

@William III : Check if the Countess Road flat was in the Eleanor Palmer catchment area last year and it can all make sense. Saves private school fees !

@TheRhino I was waiting for the QI klaxon

If I look at that FT property graph for prime properties in London, then it seems to be at about 130 in 2018 ten years after London at 100. That is only 2.66% compound growth. But the low point looks something like 70 in early 2009, which gives 7.12% compound growth over the nine years from then.

But this needs to be considered in the context of what has happened to long dated UK government GILTs.

GB00B54QLM75 4% – Issued 22 Oct 2009 at 100p, now 169.62p

GB00BBJNQY21 3.5% – Issued 26 Jun 2013 at 100p, now 162.78p

GB00BYYMZX75 2.5% – Issued 21 Oct 2015 at 100p, now 127.62p

Taking GB00B54QLM75 the compounded increase in value of the bond (excluding the coupon payments received) since issue is 6.4%. It’s fallen back quite a bit from the high which was 200p on 30 August 2016 and so if I say that is roughly 7 years from issue to that point, it was 10.4% compounded increase (excluding coupon payments received). So it’s down around 15% from the peak. This doesn’t seem to be too different – in terms of correlation. Prim property prices in terms of sales properly pulled back in July/August 2016, due to the difference between exchange dates (pre brexit result) and completion dates (pos brexit result).

So I suspect prime property has slightly underperformed long dated UK GILTS and if you wanted to work it out based on leverage you could and still can buy long dated UK GILTS at 15:85 ratio (15% deposit, 85% overnight LIBOR loan + small margin).

I certainly think everything has become horribly correlated, both geographically and also across a lot of asset classes. I also agree with @zxspectrum48k in that we seem to have brought forward a lot of the future returns and priced them into assets now. That has been great for those who are asset rich (boomers, with property and DB pensions), but really bad for generations that followed who didn’t have capital that rode the wave of asset price inflation.

Wherever you look, you need a larger capital sum to secure the same cashflow and broadly speaking, this has only got worse as you’ve gone from 2009 -> 2018, year by year. I don’t see why we would expect property to be any different.

This explains just why so many DB pension schemes have been having huge problems with valuations of assets going up through asset price inflation, but liabilities rising faster due to plummeting future returns via projected discount rates. It also explains why workers of the past 10 year have had wage increases suppressed so that employers can make ‘deficit reduction contributions’.

It’s also worth remembering the underlying situation this creates. It’s been virtually impossible to default on a standard UK residential mortgage in the South East or London for the past 20 or so years. You’ve always been able to remortgage for a larger capital amount – often without any real checks – staying below 75% LTV. For interest only mortgages, the increase in capital amount advanced has – in many cases – been more than the entire repayments made to date. I look at that and say there have been no repayments, the regulators and the regulatory environment say something very different. Even those who fall into actual arrears (buy not remortgaging quickly enough) are usually given forbearance and the arrears are capitalised into the mortgage and all that happens is the LTV increases, but is still at a sufficiently low value such that the lender doesn’t have to worry about really high LTVs. Of course, the canary in the coalmine with this is that it doesn’t work in reverse as prices soften. Mortgaged homes then have to meet mortgage payments from salaried income alone, there is no magic money tree to fall back on.

I don’t think we should underestimate the risk involved in high LTVs on inflated asset prices in residential property and unhedged interest rate risk over 25+ year terms. But trying to decide if it blows up and if it does, when, is, I think, not really possible especially as we are into generational recycling of money in property through inheritence and Bank of Mum and Dad providing significant sums to keep the cycle going.

Virtually everyone in a position of power and influence has had a vested interest in low interest rates, but events could easily overtake the ability to keep them suppressed. It does feel to me like the can has been kicked so far down the road we have ended up with a complete circumnavigation of the globe and are back where we started.

The big change for me is the volume of debt the Americans are going to have to issue from this year onwards to fund their tax cuts

I believe that US treasury issuance was about USD 0.5 trillion in 2017 and it will spike up by nearly a USD trillion a year from this year onwards. On top of this the American central bank is selling treasury bills on its balance sheet and not just taking the cash when its existing bills mature (I could be wrong about the latter).

This is a big change from the 2009-2014 position when central banks were buying their own debt stock on a huge basis. Since 2014 only the ECB and the Japanese have kept bond buying

Now all of a sudden we go from a position where there was a scarcity of benchmark assets to a lot being on offer

An extra half a trillion + USD of debt is a lot to shift every year

It all feels a bit ‘calm before the storm’, my share prices are way down even though you’d have thought the market would have gotten used to Trump mouthing off insanities. Then the modest amount I put in indirect property via a P2P site seems to be turning more illiquid by the day with more projects stalling or buildings failing to sell. What’s worrying is that that stagnation isn’t only in the SE, it’s UK wide and the firesales to date have been at a price half or even a third of what was used for the original reassurance LTV, so obviously the valuations are candyfloss.

Anecdotally, seeing a lot of acquaintances money moving out of prime property in London and out to the countryside, purchasing land/ farms for long term gains (tenant farmers, subsidies etc). Pre-empting a post-Brexit subsidy push?

From a more provincial standpoint the market appears strong in some postcodes, weak in others, but not uniformly down. Downside of globalisation?

@FI Warrior, I am surprised to hear your shares are way down. Mine (ETFs and tracker funds) are down around 3-4% this year. Perhaps you lack diversification?

@Naeclue, it’s about 10% down now, so my dismay by some people’s estimation is an exaggeration, I think it’s more I was surprised because I thought that these were defensive stocks, so supposed to perform better than the average in shaky times. I’m a timid investor overall, because I don’t have much leeway to make mistakes, so this is the one aspect of my portfolio I force myself to be daring with to get growth and actually use an actively managed fund. The only thing that helps me steel my nerve is that I can’t draw my private pension for years still because of my age, so if there’s a crash now and it takes 10 years I can handle it. (So all-in-all you’re most probably right, my shares are in too few companies)