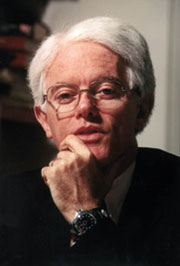

The US fund manager Peter Lynch may have been the best growth investor that ever lived. He was certainly their best writer.

Lynch wrote 1 the classic One Up on Wall Street. It’s an insanely easy-to-read introduction to a style of investing that netted Lynch an average annual return of 29% over 13 years.

That’s enough to turn £1,000 into £27,000, incidentally. If only all fund managers delivered that kind of return, they’d be worth the fees!

Of course most don’t, which is why passive index funds are the best place for most investors’ money.

13 signs of a good share to buy

For those of us who actively speculate with some of our ill-gotten gains, however, following in Lynch’s footsteps is irresistible. Not just because of his track record, but because unlike Ben Graham or Walter Schloss, he makes investing sound so much darn fun!

Like all great growth investors (as opposed to those value curmudgeons) Lynch was an incurable optimist, prepared to suspend his disbelief to see how a company’s earnings could grow.

Key to this was developing a ‘story’ about a share – the elevator pitch for why Lynch had invested in it.

But companies always promise jam tomorrow, and Lynch’s method was hardly to go for the most exciting story in town. Rather, he looked for 13 attractive characteristics in a share, which he spelled out in a lovely chapter in One Up On Wall Street.

Re-reading it on a train trip to visit fellow Monevator writer The Accumulator recently, I decided it would be fun to rip off recall these 13 pointers, and to look for examples from the UK market today.

“When somebody says ‘Any idiot could run this joint,’ that’s a plus as far as I’m concerned, because sooner or later any idiot probably is going to be running it!” – Peter Lynch

1. It sound dull – or even better ridiculous

Lynch’s perfect company has a dopey name that stockbrokers are embarrassed to mention on CNBC: Bob Evans Farms, say, or the long forgotten Pep Boys – Manny, Joe, and Jack. Who would want to invest in that?

Good British equivalents include: UK Coal; M.P. Evans Group; and Shanks Group. Dullards all. Bad names belong to mining firm Xstrata, and ‘Essenta’ – the latest moniker for Goodfellas pizza maker Northern Foods.

2. It does something dull

One of my favourite UK listed companies is James Halstead. If the boring name doesn’t send you to sleep, its business will. James Halstead a world leader in vinyl flooring.

Zzzzz! But just look at the share price and dividend record…

Exciting companies blow up or get overhyped, or both. SuperGroup makes sexy men’s fashion AND has a sexy name, which is a dangerous combination.

3. It does something disagreeable

Lynch wouldn’t want to invest in Apple at $300 a share. Not because Apple isn’t a great company, but because who wouldn’t want to own a wonderful life-enhancing company like Apple? Who wouldn’t tell their friends? Who wouldn’t puff the price up even further?

Instead, Lynch says look for companies that do something disagreeable or possibly obscene. The aforementioned Shanks is in waste management. Condom maker SSL used to be a great one – and it had a dishwater dull name – but sadly Unilever recently snapped it up.

4. It’s a spin-off

Many great companies started life as spin-offs. So did loads of doomed companies, but any one tick on this checklist isn’t a reason to invest. You need a whole lot of ticks – plus good financials – to be confident.

Spin-offs are good for two main reasons: Firstly, they’re often well funded otherwise they can’t be spun away, and secondly they may do better outside of the dead hand of a bureaucracy.

Two that spring to mind in the UK are Autonomy spin-off Blinx and the stamp specialist Stanley Gibbons. Oh, and Carphone Warehouse is doing better since it was spun-off by Talk Talk, too. It’s got serious about retail, linking up with the mighty Best Buy here and in the US.

5. The institutions don’t own it, and the analysts don’t follow it

Pretty self-explanatory – if the City is already in love with your share, who is left to buy it?

Lots of tiny oil and mining companies used to fit into this category, but the past ten years has seen them outed. The neglected tech sector might be a better place to forage for forgotten companies today.

6. The rumours abound: It’s involved with toxic waste and/or the mafia

If your company really is messing with radioactive compost or the Mob, your investment is doomed. What Lynch is getting at here is that a slightly messy company with a bad reputation can sometimes trade far too cheaply out of fear. You’d buy it ahead of the restoration of its reputation.

B.P. is an obvious candidate – after the media firestorm that followed the oil leak, many fund managers dumped it to avoid tricky questions. Tobacco and even drug companies sometimes sit in this bracket.

My investment at the height of the credit crisis in Prodesse, a US mortgage investment trust, definitely involved an element of this.

7. There’s something depressing about it

Perhaps the best share in this category in the UK is Dignity. While its name is a bit too snappy, its business – selling coffins and burial costs up-front – isn’t anything a young Cityboy wants to think about.

I almost picked up these shares earlier in the year. On the numbers it looked great, but thoughts of the grave loomed large and I went for a walk in the sun with an ice cream instead. Worth thinking about.

8. It’s in a no-growth industry

Careful. The idea is not to invest in a doomed industry (there aren’t many whalebone processors left on the London Stock Exchange) but rather in a sector that isn’t going anywhere fast.

The reason? Smart kids from Harvard and Cambridge and Imperial and MIT all want to create the next Google or Twitter. They don’t want to launch the next Carrs Milling (grinds seed) or British American Tobacco (looks bad on your Guardian Soulmates profile).

With luck, your boring company will be left alone to quietly absorb competitors and grow in its stagnant pool for years to come.

9. It’s got a niche

Lynch’s niches aren’t the same thing as a ‘market position’. ARM designs chips, but so does Intel and Imagination Technologies and many more.

A better niche for Lynch is a gravel pit.

Sutton Harbour Group would pass his test. This company owns and operates Plymouth City Airport and Sutton Harbour, amongst other things. Nobody is going to be building rival airports or boatyards in Plymouth anytime soon.

10. People have to keep buying it

Think Diageo, Glaxo, Greggs, and British American Tobacco. They all make consumable products.

So does the aforementioned SuperGroup, but you don’t have to buy and wear t-shirts with made-up Japanese writing splashed on the front (at least not outside of certain Mancunian nightspots) so that’s not such a good ‘un on this measure, either.

The reason for preferring consumables companies is obvious – the customers have to come back for more, again and again. In contrast, I might only buy a new games console every five years – plenty of time for me to decide to buy a rival’s shiny one next time

11. It’s a user of technology

Lynch prefers companies that employ technology to make more money, as opposed to companies that merely make money from technology.

The smart application of technology has transformed supermarkets and banks and oil exploration and many more sectors. An awful lot of computer companies have gone bust along the way.

12. The insiders are buying

You can track directors’ share deals in newspapers like the Financial Times at the weekend, or via services like Digital Look.

If the company execs admire the company they run so much they’ll pony up to own more of it, that can be a good sign. They at least know whether they’re fibbing in the annual reports.

It’s not always a positive signal. Rok went bust, and key directors were buying just weeks before its demise! Poor judgment can extend from the boardroom to the broking account, it seems.

13. The company is buying back its own shares

Buybacks were rarer in Lynch’s day. Many company directors now routinely use company profits to buy and cancel the company’s own shares, as opposed to paying dividends. Buy backs are an easy way to boost earnings per share, and thus for directors to hit their targets and generate those lovely bonuses.

Share buy backs do suggest the company is throwing off cash, though, and may indicate the company is cheaply valued.

And there are certainly worse things a director can do with your money. BHP Billiton resumed a $13 billion buyback programme after abandoning an exceptionally expensive bid. Shareholders probably had a lucky escape!

Inspired by Peter Lynch’s thoughts on what to look for in a share? You really should buy One Up on Wall Street (US readers here

).

- Okay, and his ghost, John Rothchild[↩]

Comments on this entry are closed.

Very nice, thanks for that. Can we take it you are not long Supergroup plc? 😉

I’m a little surprised to see stock buybacks as a positive indicator there; I always worry they mean management has run out of ideas and/or is just massaging EPS, as you mention.

i thought hindsight has always shown share buybacks to be a bit of a waste?

Not sure i agree that BHP shareholders escaped there. Cornering the market in potash seems like a one way bet to me.

@Roym – Well, buybacks are in theory a good use of cash if the alternative financing (debt) is cheap, or if companies have so much cash that they have to return it and yet think buying back shares is more efficient than enabling investors to invest for themselves.

In general I agree, I’d rather have dividends to spend as I choose!

The Potash deal had all kinds of sweets in it for the Canadian government that looked uncompetitive to me.

@Lemondy – I think SuperGroup have excellent management, a boss who says all the right things, and a solid roll out plan. The trouble is it’s such an attractive share to buy and own – sort of anti all these measures from Lynch – that everyone after growth shares is sure to pick it up, and has probably done so already. If it keeps growing at 50% or so it won’t matter for a bit, but probably a longer way to fall because of it!

Great summary! You reminded me I have to go reread his book.

.-= Investor Junkie on: Free Stock Trading With Zecco Trading =-.

I lived Peter Lynch’s writings and try to follow his way of investing as much as possible. Is it me, though, or is there a lack of UK PLCs buying back their own shares? I remember Glaxo being slated for it doing it not so long ago, but the rest of the mega-caps seem to issue new shares year after year. Does anyone know why there is such a difference between here and the US?