I am at that age where children start magically appearing in my friends’ and families’ lives.

And while I wait in vain for anyone to ask for football tips or fashion advice for the next generation, their parents – and grandparents – often ask me how they can provide financial help for their youngest loved ones.

It’s great to start saving and investing for a child as soon as possible. In fact as a sad cool accountant, I feel it’s the best gift you can give them! (Barring a copy of My First Guide To Double-Entry Bookkeeping – the illustrated edition, naturally).

Of course all the standard personal finance advice still applies – and make sure you can afford any support you give others.

Much of this will come down to personal circumstances, but something everyone needs to think about is which investment platform you choose. (More on that in a bit!)

Two platforms and three factors

There are two types of easy-to-set-up tax efficient vehicles aimed at kids:

- Junior ISAs (JISAs)

- Self-invested Personal Pension (SIPPs).

To decide which option is best, we can boil the choice down to three factors: control, efficiency, and access.

- Control – How much control you can exercise over the money that you give once it’s left your wallet? (On a sliding scale from “It’s theirs now, let’s pray they don’t go to Ibiza” to “Well, technically it’s your money little Jonathan / Gemima, but…”).

- Efficiency – How much bang for your buck do you can get from gifting money? (Spoiler alert: It can be a lot).

- Access – How and when is the money accessible?

The best choice for you will depend on how you feel towards each of these factors.

JISA

The 2020/21 limit for a JISA is £9,000. As with a standard ISA, no tax is payable on any interest or gains made within the JISA wrapper.

The JISA option is open to anyone under 18, who is resident in UK and who doesn’t have a Child Trust Fund (CTF).

Just like regular ISAs there are two types of JISA: Cash and Stocks & Shares. We’ll focus on the Stocks & Shares flavour.

How to JISA

A parent or guardian opens and manages the JISA account. It must be a parent or guardian – it can’t be a grandparent, for example.

What you will require to open the account varies. But you will at least need to ID the parent (also called the Registered Contact). You may also have to provide the parent’s birth certificate or National Insurance or passport number. The process is straightforward and takes about five minutes.

Note that while a parent opens and manages the account, money in a JISA is – legally speaking – the child’s money. The child ‘takes back control’ (!) aged 16. And they can start to withdraw money from age 18, at which point the JISA converts into a regular ISA.

Those aged 16 and 17 can also contribute into an adult Cash ISA (but not an adult stocks and shares ISA, where you need to be 18). They can contribute up to the £20,000 in the tax year. This is in addition to any money paid into their JISA.

It’s easy to put money into a JISA. You typically go to the provider’s website and enter the relevant account and payment details.

Anybody can put money in like this – you don’t need the account holder to do it for you (though it might be best to let them know!)

However only the parent / registered contact can change the account (from say a Cash ISA to a Stocks and Shares ISA) or switch provider or edit account details.

Most providers offer you the option to fund the JISA with lump sums. Some providers such as AJ Bell Youinvest have no minimum lump sum.

You can also make regular contributions. From my research, The Share Centre has the lowest minimum monthly contribution rate at £10 per month.

Factors to consider when choosing a Junior ISA:

Think about:

- Control – Once the money is in the JISA account, it’s the child’s. The parent manages it (not anyone else) but at age 18 the child can blow it all on craft beers and glamping (*shudder*).

- Efficiency – The ISA wrapper means there’s no tax on income or capital gains. Up to 18 years of compounded and globally diversified investing should lead to some nice juicy gains (assuming Kanye West doesn’t make it to the Oval Office). Particularly for grandparents, JISAs are an effective way to pass down money and avoid inheritance tax. Monthly contributions made out of income are exempt from inheritance tax.

- Access – The money is locked in until the child is aged 18, and accessible thereafter. This makes a JISA suitable for saving for a house deposit, first car, university costs, or a wedding.

In choosing a JISA provider think about:

- Cash or shares? With a Stocks & Shares ISA there is the potential for greater returns, at the risk of capital loss. (But with a planning horizon of as long as 18 years, time is on your side in the stock market.)

- These can vary significantly between providers. Most providers JISAs have the same charges as their regular ISAs. See the Monevator comparison table.

- Consider whether transfers in are allowed, and if there are charges from transfers out.

- Range of investments. Some providers only offer a limited range of investible funds or investments. Identify your investment goals and then find a provider to meet those aims.

Junior SIPP

The alternative to a JISA is a Junior SIPP.

You can contribute money into a child’s pension from any age. It’s never too soon to get that Warren Buffett snowball rolling…

(You can contribute into anyone’s SIPP, incidentally – whether they’re an adult or a child. Though it’d be a bit weird to contribute to a stranger’s pension!)

Assuming your child is a non-earner – those work-shy toddlers – the maximum you can contribute into their Junior SIPP is £3,600 gross per year (that is including tax relief).

Remember that the contributor cannot claim tax-relief. Only the recipient can.

The mechanics are otherwise very similar to a JISA. Again, the parent will manage the account for children under the age of 18. Family and friends can add money to a Junior SIPP in much the same way as a JISA.

Also like JISAs, investments in SIPPs are free from income and capital gain taxes. (That is, until the money comes to be withdrawn. Income taken from a pension may be taxable, depending on personal circumstances.)

Contributions into a SIPP are usually free from inheritance tax, providing they are contributions out of income that leave the transferor with enough income to maintain their usual standard of living. In addition, everyone has a £3,000 per year annual exemption. That is, you can gift £3,000 a year and it’s free of inheritance tax. As mentioned above, the maximum you can contribute per year into a non-earners’ SIPP is £3,600 gross (after including tax relief).

Again, both lump sums and regular savings can be used to fund the account.

On the downside, SIPP money is only accessible from age 55. This threshold is set to rise to 57 in 2028. It might go up further in the future.

Decision factors when taking the SIPP route

When choosing a Junior SIPP think about:

- Control – It’s the child’s money, but unlike with a JISA they can’t access it until they’re much older. Hopefully the child will have ‘matured’ by their 50s. (Though maybe that means less chance of strippers but more chance of Lambos?)

- Efficiency – As with a JISA, a SIPP is income tax and capital gains tax efficient. Contributing into somebody else’s pension is particularly helpful if you’re at risk of breaching the Pension Lifetime Allowance. It can also result in one of the highest ‘tax savings’ that I’m aware of – if the child is a 40% taxpayer then the family can net a 90% tax saving. (See the bonus appendix below for the maths.)

- Access – The big downside. Money in a SIPP isn’t accessible until your 50s. That may represent a very long wait. This makes a Junior SIPP a suitable option for retirement wealth building, but not for living costs or big events.

- Your Pension Lifetime Allowance. One reason you might choose to go for a Junior SIPP instead of a JISA is if you are getting close to the Lifetime Allowance. This might make diverting your pension contributions to somebody else more tax efficient for you, if it’s an option.

Choosing a SIPP provider is very similar to choosing a JISA, except that in addition to the usual broker platforms there are also personal pension providers that offer low-cost, low-contribution options, at the expense of a narrower investment selection.

Why not have both?

If you can afford it – and you love the children that much – you could go for both a JISA and a SIPP and contribute to each to maximise the respective benefits.

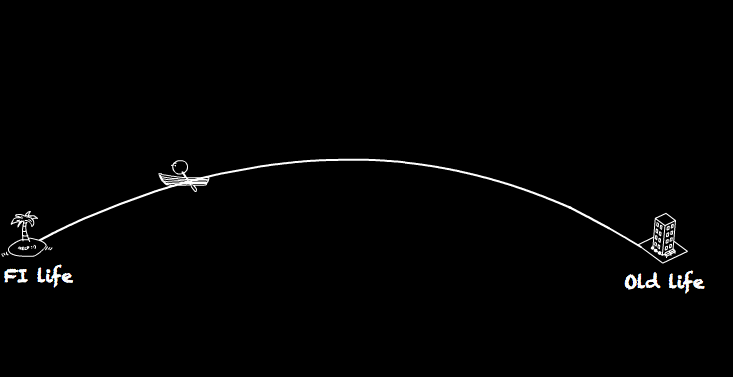

Either way, any money given to children that has a chance to compound for at least 18 years – and multiples of that in a SIPP – should be very gratefully received.

But as we cautioned at the start, make sure your planning takes into account your own retirement provisions and other financial commitments, too.

Read all The Detail Man’s previous posts on Monevator.

Bonus appendix: Worked example of (crazy high) 90% tax relief

Parent puts £3,000 into child’s SIPP (using £3,000 annual IHT exemption)

Saving 40% x £3,000 = £1,200 in IHT relief

The child receives £3,000 plus £750 relief at source

Calculated as £3,000 x 25% = £750 tax relief

If the child is a 40% tax rate payer, they can claim a further 20% through self-assessment:

£3,000 x 25% = £750 tax relief

That gives total tax relief of: £2,700 (£1,200 + £750 + £750) on a gift of £3,000. Equivalent to 90% tax relief!